Moments of Observation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martin Cloonan Introduction an Attack on the Idea of America

MUSICAL RESPONSES TO SEPTEMBER 11TH: FROM CONSERVATIVE PATRIOTISM TO RADICALISM Martin Cloonan Introduction I want to propose something very simple in this paper: that the attacks which took place on 11 September 2001 were attacks on the very idea of America. This is not a new idea. It was cited by the New York Times soon after the attack and subsequently by the cultural critic Greil Marcus (2002). But what I want to add is that as time went on it became clear that the mu- sical responses which were made were defences of America. However, there were not uniform responses, but diverse ones and that is partly be- cause the idea of America is not settled, but is open to contestation. So what I want to do in the rest of this paper is to first examine notion that the attacks on 11 September were an attack on the idea of America, look briefly at the importance of identity within popular music, chart initial musical reactions to the events and then look at longer term reactions. An attack on the idea of America The attacks on 11 September were strategically chosen to hit the symbols of America as well as the reality of it. The Twin Towers symbolised American economic power, the Pentagon its military might. This was an attack on the psyche of America as well as its buildings and people. Both the targets were attacked for propaganda purposes as much as military ones. What more devastating way could have been found to show rejection of America and all it stands for? But the point I want to note here is that America itself is a contested notion. -

KALAUAO STREAM BRIDGE HAER No. HI-117

KALAUAO STREAM BRIDGE HAER No. HI-117 (Kalauao Stream Eastbound Bridge & Kalauao Stream Westbound Bridge) Kamehameha Highway and Kalauao Stream Aiea Honolulu County Hawaii PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Oakland, California HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD KALAUAO STREAM BRIDGE (Kalauao Stream Eastbound Bridge & Kalauao Stream Westbound Bridge) HAER No. HI-117 Location: Kamehameha Highway and Kalauao Stream Aiea City and County of Honolulu, Hawaii U.S.G.S. Topographic map, Waipahu Quadrangle 1998 (7.5 minute series) Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates NAD 83: 04.609850.2364650 Present Owner: State of Hawaii Present Use: Vehicular Bridge Significance: The Kalauao Stream Bridge is a significant resource in the history of Oahu's road transportation system. It is significant at the local level for its association with the development of this section of Kamehameha Highway, and the adjacent Aiea and Pearl City settlements, which grew into suburbs from their initial establishment as a sugarcane plantation and a train-stop “city,” respectively. Historian: Dee Ruzicka Mason Architects, Inc. 119 Merchant Street Suite 501 Honolulu, HI 96813 Project Information: This report is part of the documentation for properties identified as adversely affected by the Honolulu Rail Transit Project (HRTP) in the City and County of Honolulu. This documentation was required under Stipulation V.C. (1, 2) of the Honolulu High-Capacity Transit Corridor Project (HHCTCP) Programmatic Agreement (PA), which was signed by the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Transit Administration, the Hawaii State Historic Preservation Officer, the United States Navy, and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. -

Music Playlist Auggie: 1

Music Playlist Auggie: 1. Ugly- Sugababes This links to Auggie because throughout the book Auggie gets more comfortable with his face being different and this is linked to the lyrics “ i got real comfortable with my own style”. the lyrics “But there will always be the one who will say something bad to make them feel great” this links to Julian asking if Auggie was in a fire and saying he looks like Darth Sideous. 2. This is me- Keala Settle This song links to Auggie because he works his way to accepting himself for who he is. The lyrics “I won’t let them break me down” Is linked to Auggie not letting people hurt him and he ignores the mean comments people make. The lyrics “I’m not scared to be seen” is linked to Auggie not getting upset or hide away when people stare at him. Via: 1. Ok not to be ok- Demi Lovato and Marshmello This song links to Via because she does not have to act like she is ok when something is wrong just because her parents don’t pay as much attention to her as Auggie. The lyrics “Or give up when you’re closest” is linked to Via because in the book it says if she struggles on something she works it out on her own, so Via doesn’t give up until she has figured it out. 2. History- One Direction This links to Via because her and Miranda were best friends and had a lot of history. The lyrics “Thought we were going strong I thought we were holding on” links to Via because at the start of high school she found out Miranda was ditching her in the summer holidays and their friendship was falling apart. -

Walker ————————————————————————————————————————————— Birth: Abt 1535, Of, Ruddington, Notinghamshire, England

Family History Report 1 Thomas Walker ————————————————————————————————————————————— Birth: abt 1535, Of, Ruddington, Notinghamshire, England Spouse: UNKNOWN Birth: abt 1539, Of, Ruddington, Notinghamshire, England Children: Gervase (~1566-1642) Thomas (~1570-) William (~1572-1621) 1.1 Gervase Walker ————————————————————————————————————————————— Birth: abt 1566, Ruddington, Nottinghamshire, England Death: 1 Jul 1642 He was buried July 1, 1642 in St. Columb’s Cathedral Church, Londonderry, England. Children: George (~1600-1677) 1.1.1 George Walker ————————————————————————————————————————————— Birth: abt 1600, Dublin, Ireland Death: 15 Sep 1677, Melwood, England Spouse: Ursula Stanhope Birth: abt 1642, Melwood, Yorkshire England Death: 17 May 1654, Wighill Yorkshire England Children: George (<1648-1690) 1.1.1.1 George Walker ————————————————————————————————————————————— Birth: bef 1648, Of, Wighill, Yorkshire, England Death: 1 Jul 1690, Donaoughmore, Tyrone, Ireland Died July 1, 1690 in Battle of Boyne, Seige of King James II Spouse: Isabella Maxwell Barclay Birth: abt 1644, Of, Tyrone, Ireland Death: 18 Feb 1705 Children: John (1670-1726) George (~1669-) Gervase (~1672-) Robert (~1677->1693) Thomas (1677-) Mary (~1679-) 1.1.1.1.1 John Walker ————————————————————————————————————————————— Birth: 1670, Moneymore, Londonferry, Ireland Death: 19 Oct 1726 Page 1 Family History Report Spouse: UNKNOWN Birth: abt 1674, Of, Moneymore, Derry, Ireland Children: John (~1697-~1742) Robert (~1693-) Jane (~1699-) Isabella (~1701-) 1.1.1.1.1.1 John Walker -

1950-03 Great White Fleet Part 3

Big White Fleet Visits W aikiki - 1908 (Concluded) OFFICERS ENTERTAIN That evening was one of interest and pleasure. We had met many young la dies and we threw a party for them in the Wisconsin Junior Officers’ Mess. I’ll never forget the feminine shriek that came from pretty lips as one of our guests bumped her head into a hammocked Edwin North McClellan, who has written bluejacket swinging just outside the this article, has a background of unusual mess-room entrance. experience. He circled tbe globe with tbe big white fleet in 1908 and visited Hawaii many Next day, in obedience to orders, I times and is now a resident. Retired Lt. Colonel of tbe Marine Corps, and historian, went out to Pearl Harbor (Wai Momi) editor, writer and traveller, he is presently by the OR&L and returned by automo Dean of radio commentators in Hawaii. bile. We took a ride in one of the battle ship steamers to be "sold” on the Pearl keepers, John Walker and Clifford Kim Harbor idea by the Pearl Harbor Sub- ball. Committee of the Fleet Entertainment Society turned out in its fullest Committee. After steaming around the strength, on the evening of July 20th, to Lochs we landed on the Peninsula where honor the enlisted men of the Fleet at a a fine recreation hall — resplendent with Ball staged at the Moana Hotel, Seaside Hawaiian decorations and bunting—had Hotel and Outrigger Canoe Club, in a been erected. Long" tables tastefully ar duplication of the Ball and Reception ranged a la luau was loaded with lots of given to the Officers on the 17th. -

The Carroll News

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 4-28-1961 The aC rroll News- Vol. 43, No. 13 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News- Vol. 43, No. 13" (1961). The Carroll News. 237. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/237 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The (;arroll jNew degree programs NEWS feature 'Classical' A.B. Representing John Carroll University Two new A.B. degree pro- ment of Latin or Greek. language requirement by the elec The Very Rev. Hugh E. Dunn, tion of a single language, modern University Heights 18, Ohio gramR will eventually replace S.J., President of the Univer11ity, or classical. In e.!fect, the language the present A.B. and B.S. in announced, that "the new program t·cquirement of the current B.S. in Vol. XLIII, No. 13 Friday, April 28, 1961 S.S. degrees, it was announce(! will strengthen the Bachelor of S.S. program has been extended in from the President's office Arts degree and at the same time this respect to the A.B. The A.B. provide opportunities for students Classics program, however, retains ~·esterday. seeking a classical background." the two-language requirement as One program has the title "A.D. Effective this September, Carroll formerly, except for an upgrading Pellegrino reigns IClassics" in distinction to the "A. -

An Examination of the Theories and Methodologies of John Walker (1732- 1807) with Emphasis Upon Gesturing

This dissertation has been 64—7006 microfilmed exactly as received DODEZ, M. Leon, 1934- AN EXAMINATION OF THE THEORIES AND METHODOLOGIES OF JOHN WALKER (1732- 1807) WITH EMPHASIS UPON GESTURING. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1963 Speech—Theater University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan AN EXAMINATION OP THE THEORIES AND METHODOLOGIES OP JOHN WALKER (1732-1807) WITH EMPHASIS UPON GESTURING DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By M. Leon Dodez, B.Sc., M.A ****** The Ohio State University 1963 Approved by Department of Speech ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to express my gratitude to Dr. George Lewis for his assistance In helping to shape my background, to Dr. Franklin Knower for guiding me to focus, and to Dr. Keith Brooks, my adviser, for his cooperation, patience, encouragement, leadership, and friendship. All three have given much valued time, encouragement and knowledge. ii CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................... 1 Chapter I. INTRODUCTION............................... 1 II, BIOGRAPHY................................... 9 III. THE PUBLICATIONS OP JOHN WALKE R............. 27 IV. JOHN WALKER, ORTHOEPIST AND LEXIGRAPHER .... 43 V. NATURALISM AND MECHANICALISM............... 59 VI. THEORY AND METHODOLOGY..................... 80 VII^ POSTURE AND P A S S I O N S ......................... 110 VIII. APPLICATION AND PROJECTIONS OP JOHN WALKER'S THEORIES AND METHODOLOGIES......... 142 The Growth of Elocution......................143 L a n g u a g e ................................... 148 P u r p o s e s ................................... 150 H u m o r ....................................... 154 The Disciplines of Oral Reading and Public Speaking ......................... 156 Historical Analysis ....................... 159 The Pa u s e .................................. -

A Portrait of EMMA KAʻILIKAPUOLONO METCALF

HĀNAU MA KA LOLO, FOR THE BENEFIT OF HER RACE: a portrait of EMMA KAʻILIKAPUOLONO METCALF BECKLEY NAKUINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HAWAIIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2012 By Jaime Uluwehi Hopkins Thesis Committee: Jonathan Kamakawiwoʻole Osorio, Chairperson Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa Wendell Kekailoa Perry DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Kanalu Young. When I was looking into getting a graduate degree, Kanalu was the graduate student advisor. He remembered me from my undergrad years, which at that point had been nine years earlier. He was open, inviting, and supportive of any idea I tossed at him. We had several more conversations after I joined the program, and every single one left me dizzy. I felt like I had just raced through two dozen different ideas streams in the span of ten minutes, and hoped that at some point I would recognize how many things I had just learned. I told him my thesis idea, and he went above and beyond to help. He also agreed to chair my committee. I was orignally going to write about Pana Oʻahu, the stories behind places on Oʻahu. Kanalu got the Pana Oʻahu (HWST 362) class put back on the schedule for the first time in a few years, and agreed to teach it with me as his assistant. The next summer, we started mapping out a whole new course stream of classes focusing on Pana Oʻahu. But that was his last summer. -

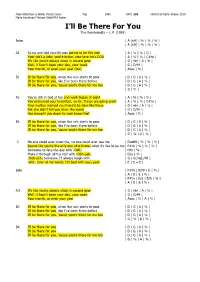

I'll Be There for You (V1) Artist:The Rembrandts

I'll Be There For You (v1) Artist:The Rembrandts. Writer:Phil Sōlem, Danny Wilde, David Crane, Marta Kauffman, Michael Skloff, Allee Willis A -2-2-2-0------------0-----2-2-2-0--------------0---- E -3---------3-1-1-3-----3--3----------3-1-1-3-----3- C -2---------------------------2--------------------------- G -0---------------------------0--------------------------- Strumming Pattern: Island Strum Intro: [G] [F] [G] [F] [G] So no one told you life was gonna be this [F] way [G] Your job's a joke, you're broke, your love life's [Gmaj7] D.O.A. [F] It's like you're [C] always stuck in [G] second gear And it [F] hasn't been your [C] day, your week Your [D] month or even your [D7] year, but Gmaj7 [G] I'll be [C] there for [D] you, when the rain starts to [G] pour I'll be [C] there for [D] you, like I've been there be-[G]fore I'll be [C] there for [D] you, 'cause you're there for me [F] too [F] [G] You're in bed at ten and work began at [F] eight [G] You've burned your breakfast so far things are going [Gmaj7] great [F] Your mother [C] warned you there'd be [G] days like these But she [F] didn’t tell you [C] when the world has [D] brought You down to your [D7] knees that [G] I'll be [C] there for [D] you, when the rain starts to [G] pour I'll be [C] there for [D] you, like I've been there be-[G]fore I'll be [C] there for [D] you, 'cause you're there for me [F] too [F] [G] [G] [C] No one could ever know me, no one could ever see me [Em] Sometimes the only one who knows what it's like to be me [Am] Someone to face the day with, [Am7] make it through -

SWAN CV Updated December 2020.Docx 12/21/20 | Cs

SWAN_CV_Updated_December 2020.docx 12/21/20 | cs CURRICULUM VITAE CLAUDIA SWAN AREAS OF EXPERTISE European art, with a focus on the Netherlands in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; art and science; early modern global encounters; Renaissance and Baroque graphic arts (prints and drawings); the history of collecting and museology; history of the imagination. EDUCATION Ph.D., Art History, 1997 Columbia University New York, NY Dissertation: “Jacques de Gheyn II and the Representation of the Natural World in the Netherlands ca. 1600” Advisor: David Freedberg (Readers: Keith P.F. Moxey, David Rosand, Simon Schama, J.W. Smit) M.A., Art History, 1987 Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, MD Thesis: “The Galleria Giustiniani: eine Lehrschule für die ganze Welt” Advisor: Elizabeth Cropper B.A. cum laude with Honors in Art History, 1986 Barnard College, Columbia University New York, NY Senior thesis: “‘Annals of Crime’: Man among the Monuments” Advisor: David Freedberg EMPLOYMENT Inaugural Mark S. Weil Professor of Early Modern Art 2021- Department of Art History & Archaeology Washington University in St. Louis St. Louis, MO Associate Professor of Art History 2003- Department Chair 2007-2010 Assistant Professor of Art History 1998-2003 Northwestern University Department of Art History Northwestern University, Evanston, IL Assistant Professor of Art History Northern European Renaissance and Baroque Art The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 1996-1998 Instructor Art Humanities: Masterpieces of Western Art Columbia University, New York, NY 1995-1996 Lecturer (for Simon Schama) 17th-Century Dutch Art and Society Columbia University Spring 1995 Research Assistant Rembrandt Research Project Amsterdam 1986 Translator, Dutch-English Meulenhoff-Landshoff; Benjamins; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; Simiolus 1986-1991 FELLOWSHIPS AND RESEARCH AWARDS Post-doctoral fellowships and awards (Invited) Senior Fellow, Imaginaria of Force DFG Centre of Advanced Studies Dir. -

The NME Singles Charts

The Chart Book – The Specials The New Musical Express Charts 1960- 1969 Compiled by Lonnie Readioff Chart History For The NME Singles Charts Between 1 January 1960 and 27 December 1969 Entry Peak Weeks on chart, Title (Number 1 Number) (Awards symbols, if any for this record in this period) (Composer) Full artist credit (if different) B-Side (Or EP/Album track listing if any charted on this chart) Label (Catalogue Number) Duration. Notes are presented below the title for some entries. Entries are sorted by artist, then by entry date and finally, in the event of ties, by peak position and finally weeks on chart. All re-entries are shown as separate entries, but track listings of any albums or EP's which re-entered the chart are not shown for their re-entries. Kenny Ball (Continued) 16.02.1962 1 11 March Of The Siamese Children (N1 #131) (Oscar Hammerstein II / Richard Rodgers) Kenny Ball and His Jazzmen If I Could Be With You Pye Jazz 7": 7NJ 2051 02:44 18.05.1962 8 11 The Green Leaves Of Summer (Dimitri Tiomkin / Paul Francis Webster) Kenny Ball and His Jazzmen I'm Crazy 'bout My Baby Pye Jazz 7": 7NJ 2054 02:48 24.08.1962 11 5 So Do I (Ian Grant / Theo Mackeben) Kenny Ball and His Jazzmen Cornet Chop Suey Pye Jazz 7": 7NJ 2056 02:38 19.10.1962 23 3 The Pay-Off (A Moi De Payer) (Sidney Bechet) Kenny Ball and His Jazzmen I Got Plenty O' Nuttin' Pye Jazz 7": 7NJ 2061 03:00 25.01.1963 10 8 Sukiyaki (Ei Rohusuke / Nakamura Hachidai) Kenny Ball and His Jazzmen Swanee River Pye Jazz 7": 7NJ 2062 03:00 19.04.1963 17 6 Casablanca (Nicolas Sakelario -

I'll Be There For

Allee Willis/Danny Wilde/ David Crane/ Pop 1995 BPM: 191 Aflyttet af Martin Krøger 2019 Marta Kauffman/ Michael Skloff/Phil Solem I’ll Be There For You The Rembrandts – L.P. (1995) Intro | A (riff) | % | % | % | | A (riff) | % | % | % | A1 So no one told you life was gonna to be this way | A | % | % | G | Your job's a joke, you're broke, your love life's DOA | A | % | % | C#m | It's like you're always stuck in second gear | G | Hm | A | % | Well, it hasn't been your day, your week | G | D/f# | Your month, or even your year (but) | Asus | % | B1 I'll be there for you, when the rain starts to pour | D | G | A | % | I'll be there for you, like I've been there before | D | G | A | % | I'll be there for you, 'cause you're there for me too | D | G | A | % | | G | % | A2 You're still in bed at ten and work began at eight | A | % | % | G | You've burned your breakfast, so far, things are going great | A | % | % | C#m | Your mother warned you there'd be days like these | G | Hm | A | % | But she didn't tell you when the world | G | D/f# | Has brought you down to your knees that | Asus | % | B2 I'll be there for you, when the rain starts to pour | D | G | A | % | I'll be there for you, like I've been there before | D | G | A | % | I'll be there for you, 'cause you're there for me too | D | G | A | % | | G | % | A | % | C No one could ever know me, no one could ever see me | Dadd9 | % | % | % | Seems like you're the only one who knows what it's like to be me | F#m | % | % | % | Someone to face the day with (Ooh) | Hm | % | Make it through all the