Planetary Praxis: on Rhyming Hope and History Paul D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interrogating the Anthropocene: Truth and Fallacy the Jus Semper Global Alliance

The Jus Semper Global Alliance In Pursuit of the People and Planet Paradigm Sustainable Human Development June 2021 BRIEFS ON TRUE DEMOCRACY AND CAPITALISM Interrogating the Anthropocene: Truth and Fallacy Opening reflections for a GTI forum1 Paul Raskin In the Anthropocene, what does your freedom mean?2 he Anthropocene concept advances the T stunning proposition that human activity has catapulted Earth out of the relatively benign Holocene into a hostile new geological epoch. The recognition of our species as a planet-transforming colossus has jolted the cultural zeitgeist and sparked reconsideration of who we are, where we are going, and how we must act. What are the implications for envisioning and building a decent future? If we care about a Great Transition, how should we think about the Anthropocene? Resonances An examination of the Anthropocene idea must start with a disturbing scientific truth: human activity has altered how the Earth functions as an integral biophysical system. For decades, evidence has mounted of anthropogenic disturbance of planetary conditions and processes, notably, the global climate, ocean chemistry, the cryosphere, the nitrogen cycle, and the abundance, diversity, and distribution of fauna and flora. Rippling synergistically across space and time, this multi-pronged disturbance compromises Earth’s stability and heightens risks of a disruptive state-shift of the system as a totality. 1 ↩ See the forum page: https://greattransition.org/gti-forum/interrogating-the-anthropocene 2 ↩ Singer-songwriter Nick Mulvey poses this question in his poignant lament “In the Anthropocene,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OYnaQIvBRAE. TJSGA/Brief/SD (B035) June 2021/Paul Raskin 1 Such pronounced human modification of the planet prompted earth scientists to propose the designation of a new geological epoch in a landmark 2000 article.3 They christened it “the Anthropocene,” an evocative neologism signifying the Age of Humanity (“Anthropos”). -

Global Citizens Movement Paul Raskin

4-6 Raskin - People's Movement_Layout 1 4/15/11 3:26 PM Page 1 feature | shared planetary consciousness Imagine All the People Advancing a Global Citizens Movement Paul Raskin How to change the world? Those concerned about the —climate change and ecosystem degradation, economic instabil - dangerous drift of global development are asking this ity and geopolitical conflict, oppression and mass migration—that left unattended might well pull us toward a bleak tomorrow. question with increasing urgency. Dominant institu - tions have proved too timorous or too venal for meet - Nonetheless, we still have time to bypass the future on offer, ing the environmental and social challenges of our though it will not be easy. Charting passage to a happier outcome time. Instead, an adequate response requires us to demands rapid emergence of ways of thinking and acting imagine the awakening of a new social actor: a coor - matched to the profound challenge posed by global transition. Our concern and accountability, indeed, our very sense of self, dinated global citizens movement (GCM) struggling must expand across the barriers of space and time to embrace the on all fronts toward a just and sustainable planetary whole human family, the ecosphere, and the unborn. We stand at civilization. Existing civil society campaigns remain an inflection point of history full of peril, but also promise, if we fragmented and therefore powerless to leverage holistic can come together in a joint venture: creating a culture of solidar - transformation. To create an alternative vision and ef - ity and politics of trust within a movement to build democratic institutions for peace, justice, and sustainability. -

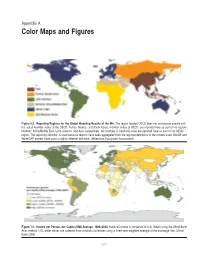

Color Maps and Figures

Appendix A Color Maps and Figures Figure 6.3. Reporting Regions for the Global Modeling Results of the MA. The region labeled OECD does not correspond exactly with the actual member states of the OECD. Turkey, Mexico, and South Korea, member states of OECD, are reported here as part of the regions Northern Africa/Middle East, Latin America, and Asia, respectively. All countries in Central Europe are reported here as part of hte OECD region. This reporting definition is used because regions have been aggregated from the regional definitions of the models used. IMAGE and WaterGAP models have used a slightly different definition. (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment) Figure 7.5. Income per Person, per Capita (GNI) Average, 1999–2003. National income is converted to U.S. dollars using the World Bank Atlas method. U.S. dollar values are obtained from domestic currencies using a three-year weighted average of the exchange rate. (World Bank 2003) 517 ................. 11411$ APPA 10-21-05 13:44:38 PS PAGE 517 518 Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Scenarios Figure 7.6a. Average GDP per Capita Annual Growth Rate, 1990–2003 Figure 7.6b. Average GDP Annual Growth Rate, 1990–2003 (Based on data downloaded from the online World Bank database and reported in World Bank 2004.) ................. 11411$ APPA 10-21-05 13:46:32 PS PAGE 518 Color Maps and Figures 519 Figure 7.10. Energy Intensity Changes with Changes in per Capita Income for China, India, Japan, and United States. Historical data for the United States since 1800 are shown. Data are converted from domestic currencies using market exchange rates. -

Great Transition: the Promise and Lure of the Times Ahead

Great Transition The planetary phase of history has begun, its ultimate shape profoundly uncertain. Will global development veer toward a world of impoverished people, cultures and nature? Or will there be a Great Transition toward a future of enriched lives, human solidarity and environmental sustainability? Though perhaps improbable, such a shift is still possible. The essay examines the historic roots of this fateful crossroads for world Great Transition development, and scans different scenarios that can emerge from contempo- The Promise and Lure of the Times Ahead rary forces and contradictions. This work of engagement as well as analysis points to strategies, values and choices for advancing a Great Transition. The book synthesizes the insights of the Global Scenario Group. Convened RASKIN • BANURI • GALLOPÍN • GUTMAN • HAMMOND SWART • KATES in 1995 by the Stockholm Environment Institute, the Group engages diverse participants in an exploration of the requirements for a sustainable world. Many global and regional assessments have relied on the Group’s research. PAUL RASKIN TARIQ BANURI GILBERTO GALLOPÍN PABLO GUTMAN AL HAMMOND ROBERT KATES ROB SWART Great Transition The Promise and Lure of the Times Ahead PAUL RASKIN, TARIQ BANURI, GILBERTO GALLOPÍN, PABLO GUTMAN, AL HAMMOND, ROBERT KATES, ROB SWART A report of the Global Scenario Group Stockholm Environment Institute - Boston Tellus Institute 11 Arlington Street Boston, MA 02116 Phone: 1 617 266 8090 Email: [email protected] SEI Web: http://www.sei.se GSG Web: http://www.gsg.org SEI PoleStar Series Report no. 10 © Copyright 2002 by the Stockholm Environment Institute Cover: Stephen S. Bernow Devera Ehrenberg ISBN: 0-9712418-1-3 C Printed on recycled paper To our grandparents, who labored and dreamed for us. -

Climate Change Redemption Through Crisis

Climate Change Redemption through Crisis Sivan Kartha GTI Paper Series 13 Frontiers of a Great Transition Tellus Institute 11 Arlington Street Boston, MA 02116 Phone: 1 617 2665400 Email: [email protected] Tellus Web: http://www.tellus.org GTI Web: http://www.gtinitiative.org © Copyright 2006 by the Tellus Institute Series Editors: Orion Kriegman and Paul Raskin Manuscript Editors: Faye Camardo, Loie Hayes, Pamela Pezzati, Orion Stewart Cover Image: Stephen Bernow and Devra Ehrenberg Printed on recycled paper The Great Transition Initiative GTI is a global network of engaged thinkers and thoughtful activists who are committed to rigorously assessing and creatively imagining a great transition to a future of enriched lives, human solidarity, and a healthy planet. GTI’s message of hope aims to counter resignation and pessimism, and help spark a citizens movement for carrying the transition forward. This paper series elaborates the global challenge, future visions, and strategic directions. GTI Paper Series Frontiers of a Great Transition The Global Moment and its Possibilities 1. Great Transition: The Promise and Lure of the Times Ahead (Raskin, Banuri, Gallopín, Gutman, Hammond, Kates, Swart) Planetary civilization, global scenarios, and change strategies 2. The Great Transition Today: A Report From the Future (Raskin) An optimistic vision of global society in the year 2084 Institutional Transitions 3. Global Politics and Institutions (Rajan) Principles and visions for a new globalism 4. Visions of Regional Economies in a Great Transition World (Rosen and Schweickart) Reinventing economies for the twenty-first century 5. Transforming the Corporation (White) Redesigning the corporation for social purpose 6. Trading into the Future: Rounding the Corner to Sustainable Development (Halle) International trade in a sustainable and equitable world 7. -

Great Transition Great

Great Transition The planetary phase of history has begun, its ultimate shape profoundly uncertain. Will global development veer toward a world of impoverished people, cultures and nature? Or will there be a Great Transition toward a future of enriched lives, human solidarity and environmental sustainability? Though perhaps improbable, such a shift is still possible. The essay examines the historic roots of this fateful crossroads for world Great Transition development, and scans different scenarios that can emerge from contempo- The Promise and Lure of the Times Ahead rary forces and contradictions. This work of engagement as well as analysis points to strategies, values and choices for advancing a Great Transition. The book synthesizes the insights of the Global Scenario Group. Convened RASKIN • BANURI • GALLOPÍN • GUTMAN • HAMMOND SWART • KATES in 1995 by the Stockholm Environment Institute, the Group engages diverse participants in an exploration of the requirements for a sustainable world. Many global and regional assessments have relied on the Group’s research. PAUL RASKIN TARIQ BANURI GILBERTO GALLOPÍN PABLO GUTMAN AL HAMMOND ROBERT KATES ROB SWART Great Transition The Promise and Lure of the Times Ahead PAUL RASKIN, TARIQ BANURI, GILBERTO GALLOPÍN, PABLO GUTMAN, AL HAMMOND, ROBERT KATES, ROB SWART A report of the Global Scenario Group Stockholm Environment Institute - Boston Tellus Institute 11 Arlington Street Boston, MA 02116 Phone: 1 617 266 8090 Email: [email protected] SEI Web: http://www.sei.se GSG Web: http://www.gsg.org SEI PoleStar Series Report no. 10 © Copyright 2002 by the Stockholm Environment Institute Cover: Stephen S. Bernow Devera Ehrenberg ISBN: 0-9712418-1-3 C Printed on recycled paper To our grandparents, who labored and dreamed for us. -

Socio-Economic Scenario Development for Climate Change

Socioeconomic Scenario Development for Climate Change Analysis WORKING PAPER Elmar Kriegler, Brian O’Neill, Stephane Hallegatte, Tom Kram, Robert Lempert, Richard Moss, Thomas Wilbanks Published 18 October 2010 Author affiliations: Elmar Kriegler, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Telegrafenberg A31, 14473 Potsdam, Germany. Email: kriegler@pik‐potsdam.de, Tel: (+49) (0)331 288‐2616. Brian C. O’Neill, National Center for Atmospheric Research, PO Box 3000, Boulder, CO, 80307, USA. Email: [email protected], Tel: (+1) 303‐497‐8118. Stéphane Hallegatte, Centre International de Recherche sur l’Environnement et le Développement (CIRED) and Ecole Nationale de la Météorologie, Météo‐France, 45bis Av. de la Belle Gabrielle, F‐94736 Nogent‐sur‐Marne, France. Email : hallegatte@centre‐cired.fr, Tel : (+33) (0)1 43 94 73 73. Tom Kram, PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, PO Box 303, 3720 AH Bilthoven, The Netherlands. Email: [email protected], Tel: (+31) (0)30 274‐3554. Richard H. Moss, Joint Global Change Research Institute, Pacific Northwest National Labs / Univ. of Maryland, 5825 University Research Court, Suite 3500, College Park, MD 20740, USA. Email: [email protected], Tel: (+1) 301‐314‐6711. Robert Lempert, RAND Corp., 1776 Main St, Santa Monica, California, USA. Email: [email protected], Tel: (+1) 310‐393‐0411 x6217. Thomas J. Wilbanks, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 1 Bethel Valley Road, Oak Ridge, TN 37831‐ 6103, USA. Email: [email protected], Tel: (+1) 865‐574‐5515. 1 Abstract: Socio‐economic scenarios constitute an important tool for exploring the long‐term consequences of anthropogenic climate change and available response options. They have been applied for different purposes and to a different degree in various areas of climate change analysis, typically in combination with projections of future climate change. -

There's a Future. Visions for a Better World

System Shift: Pivoting Toward Sustainability Paul D. Raskin >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> THE LARGER CHALLENGE The world’s dalliance with sustainable development has been rather platonic, beguiled by the idea and indifferent to the practice. Affirming sustainability in the abstract is an easy virtue: the call to bequeath an undiminished world to our descendants expresses a moral imperative that resonates with survival and empathic instincts deep in the human psyche. When these good intentions alight in the contentious sphere of public policy, however, the clamor of immediate self-interest often silences appeals for collective foresight and responsible action. Sustainability hangs suspended where grave crises gather in the lacuna between aspiration and deed. When the Rio Earth Summit of 1992 adopted its optimistic Agenda 21 blueprint for a new century, the dream of a sustainable future reached an apogee. By contrast, the Rio+20 Summit of 2012 could muster only constricted vision and anodyne recommendations, bookending the world’s two-decade descent from hope and commitment to intransigence and inertia. This triumph of inaction has bred a Zeitgeist of apprehension among citizens attuned to deteriorating conditions, while more apocalyptic spirits succumb to resignation and despair, even nihilism. Trepidation and ennui are certainly understandable responses to our contemporary predicament. Nevertheless, to paraphrase Mark Twain’s comment on his own premature obituary, reports of sustainability’s death are greatly exaggerated. Blanca Muñoz, Retráctil (detail), 2009 Still, any exploration of a renewed basis for hope must begin with clear-eyed acknowledgement of the dire circumstances we now confront. Scientific evidence keeps mounting that current patterns of development threaten to carry the global system beyond critical thresholds into a terra incognita of destabilizing social-ecological crises (Barnosky et al. -

MAKING the GREAT Transformation S E I R E S E C N E R E F N O C E E D R a P

MAKINGTHEGREATTRANSFORMATION MAKING THE GREAT Transformation PARDEECONFERENCESERIES FREDERICK S. PARDEE CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF THE LONGER-RANGE FUTURE Boston University 67 Bay State Road Boston, MA 02215 tel: 617-358-4000 fax: 617-358-4001 e-mail: [email protected] www.bu.edu/pardee F A L L 2 0 0 3 Copyright © Trustees of Boston University. All rights reserved. The Pardee Center Conference Series Fall 2003 0806 795047 The Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future was established at Boston University in late 2000 to advance scholarly dialogue and investigation into the future. The over- arching mission of the Pardee Center is to serve as Frederick S. Pardee a leading academic nucleus for the study of the longer-range future and to produce serious intellectual work that is interdisci- plinary, international, non-ideological, and of practical applicability towards the betterment of human well-being and enhancement of the human condition. The Pardee Center’s Conference Series provides an ongoing platform for such investigation. The Center convenes a conference each year, relating the topics to one another, so as to assemble a master-construct of expert research, opinion, agreement, and disagreement over the years to come. To help build an institutional memory, the Center encourages select participants to attend most or all of the conferences. Conference participants look at decisions that will have to be made and at options among which it will be necessary to choose. The results of these deliberations provide the springboard for the development of new scenarios and strategies. The following is an edited version of our conference presentations. -

The Great Transition Today a Report from the Future

The Great Transition Today A Report from the Future Paul D. Raskin GTI Paper Series 2 Frontiers of a Great Transition Tellus Institute 11 Arlington Street Boston, MA 02116 Phone: 1 617 2665400 Email: [email protected] Tellus Web: http://www.tellus.org GTI Web: http://www.gtinitiative.org © Copyright 2006 by the Tellus Institute Series Editors: Orion Kriegman and Paul Raskin Manuscript Editors: Faye Camardo, Loie Hayes, Pamela Pezzati, Orion Stewart Cover Image: Stephen Bernow and Devra Ehrenberg Printed on recycled paper The Great Transition Initiative GTI is a global network of engaged thinkers and thoughtful activists who are committed to rigorously assessing and creatively imagining a great transition to a future of enriched lives, human solidarity, and a healthy planet. GTI’s message of hope aims to counter resignation and pessimism, and help spark a citizens movement for carrying the transition forward. This paper series elaborates the global challenge, future visions, and strategic directions. GTI Paper Series Frontiers of a Great Transition The Global Moment and its Possibilities 1. Great Transition: The Promise and Lure of the Times Ahead (Raskin, Banuri, Gallopín, Gutman, Hammond, Kates, Swart) Planetary civilization, global scenarios, and change strategies 2. The Great Transition Today: A Report From the Future (Raskin) An optimistic vision of global society in the year 2084 Institutional Transitions 3. Global Politics and Institutions (Rajan) Principles and visions for a new globalism 4. Visions of Regional Economies in a Great Transition World (Rosen and Schweickart) Reinventing economies for the twenty-first century 5. Transforming the Corporation (White) Redesigning the corporation for social purpose 6. -

How Do We Get There? the Problem of Action

How Do We Get There? The Problem of Action Paul Raskin Planetary Praxis Redux In our time of unprecedented interdependence and existential risk, we face a common predicament and an uncertain destiny. As the global quandary deepens and awareness spreads, the conviction that root-and-branch social change is needed to circumvent perils and seize opportunities draws more and more of us. Reaching a flourishing future requires the revitalization of the basis of planetary civilization, a Great Transition in culture and institutions.1 The vision of a better world beckons, but how do we get there? Although there are no easy answers, this much seems axiomatic: a systemic social force is needed to drive a systemic planetary shift. But what shape might such a force take, and how can we best nurture it? Since its inception in 2003, GTI has taken up the question of historic agency, building on the work of its predecessor, the Global Scenario Group. We have had episodic exchanges on the critical role to be played by a popular global movement (a “global citizens movement”) in the Great Transition story, and some of us have experimented with building collaborative campaigns to foster it.2 1 | A GTI Discussion Note But it’s been a while. The times change, and so do we. More than ever, we need stronger answers to the still-burning question of action. This note summarizes core GTI ideas developed to date, in the hope of stimulating fresh thought and debate, and perhaps new initiatives.3 The Fourth Question The conceptual framework for addressing this challenge rests on four pillars that address four associated questions: Where are we? Where are we going? Where do we want to go? How do we get there? These questions urge—in ascending degree of difficulty—critique of the existing order, analytic exploration of alternative global scenarios, normative visions of desirable outcomes, and collective action for shaping social evolution. -

Journey-To-Earthland.Pdf

JOURNEY TO EARTHLAND The Great Transition to Planetary Civilization PAUL RASKIN JOURNEY TO EARTHLAND T he Great Transition to Planetary Civilization Tellus Institute 11 Arlington Street Boston, Massachusetts 02116 www.tellus.org Copyright © 2016 by Paul Raskin Published 2016 This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license. You may share this PAUL RASKIN work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher. Requests to reprint or reproduce excerpts of Journey to Earthland should be directed to the Tellus Institute (email: info@ tellus.org). ISBN: 978-0-9978376-2-9 For the vision-keepers—yesterday’s trailblazers to a world made whole, today’s multitudes carrying it forward, and tomorrow’s travelers who may glimpse CONTENTS the destination. Author’s Preface i Prologue: Bound Together 1 Part I: Departure: Into the Maelstrom 5 The long prelude 5 Out of the cosmos 5 The second Big Bang 8 Macro-shifts 10 The Planetary Phase 13 A unitary formation 13 Adumbrations 16 A turbulent time 20 Tomorrowlands 24 Branching scenarios 24 Dramatis personae 28 Who speaks for Earthland? 31 Part II: Pathway: A Safe Passage 35 Peril in the mainstream 35 Triads of transformation 45 Through-lines 50 Rising up 59 Citizens without borders 59 Dimensions of collective action 64 Imagine all the people 66 Part III: Destination: Scenes from a Civilized Future 71 One hundred years that shook the world 71 What matters 75 One world 78 AUTHOR’S PREFACE Many places 79 Governance: the principle of constrained pluralism 84 Economy 88 o paraphrase Ray Bradbury, I write not to describe the future, but World trade 92 Tto prevent it.