Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/29/2021 05:25:26AM Via Free Access Nurses During the Anglo-Boer War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compassion and Courage

Compassion and courage Australian doctors and dentists in the Great War Medical History Museum, University of Melbourne War has long brought about great change and discovery in medicine and dentistry, due mainly to necessity and the urgency and severity of the injuries, disease and other hardships confronting patients and practitioners. Much of this innovation has taken place in the field, in makeshift hospitals, under conditions of poor Compassion hygiene and with inadequate equipment and supplies. During World War I, servicemen lived in appalling conditions in the trenches and were and subjected to the effects of horrific new weapons courage such as mustard gas. Doctors and dentists fought a courageous battle against the havoc caused by AUSTRALIAN DOCTORS AND DENTISTS war wounds, poor sanitation and disease. IN THE REAT AR Compassion and courage: Australian doctors G W and dentists in the Great War explores the physical injury, disease, chemical warfare and psychological trauma of World War I, the personnel involved and the resulting medical and dental breakthroughs. The book and exhibition draw upon the museums, archives and library of the University of Melbourne, as well as public and private collections in Australia and internationally, Edited by and bring together the research of historians, doctors, dentists, curators and other experts. Jacqueline Healy Front cover (left to right): Lafayette-Sarony, Sir James Barrett, 1919; cat. 247: Yvonne Rosetti, Captain Arthur Poole Lawrence, 1919; cat. 43: [Algernon] Darge, Dr Gordon Clunes McKay Mathison, 1914. Medical History Museum Back cover: cat. 19: Memorial plaque for Captain Melville Rule Hughes, 1922. University of Melbourne Inside front cover: cat. -

Dentistry and the British Army: 1661 to 1921

Military dentistry GENErAL Dentistry and the British Army: 1661 to 1921 Quentin Anderson1 Key points Provides an overview of dentistry in Britain and Provides an overview of the concerns of the dental Illustrates some of the measures taken to provide its relation to the British Army from 1661 to 1921. profession over the lack of dedicated dental dental care to the Army in the twentieth century provision for the Army from the latter half of the before 1921 and the formation of the Army nineteenth century. Dental Corps. Abstract Between 1661 and 1921, Britain witnessed signifcant changes in the prevalence of dental caries and its treatment. This period saw the formation of the standing British Army and its changing oral health needs. This paper seeks to identify these changes in the Army and its dental needs, and place them in the context of the changing disease prevalence and dental advances of the time. The rapidly changing military and oral health landscapes of the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century bring recognition of the Army’s growing dental problems. It is not, however, without years of campaigning by members of the profession, huge dental morbidity rates on campaign and the outbreak of a global confict that the War Ofce resource a solution. This culminates in 1921 with, for the frst time in 260 years, the establishment of a professional Corps within the Army for the dental care of its soldiers; the Army Dental Corps is formed. Introduction Seventeenth century site; caries at contact areas was rare. In the seventeenth century, however, the overall This paper sets out to illustrate the links At the Restoration in 1660, Britain had three prevalence increased, including the frequency between dentistry and the British Army over armies:1 the Army raised by Charles II in of lesions at contact areas and in occlusal the 260 years between the Royal Warrant exile, the Dunkirk garrison and the main fssures.3 In contrast, it is suggested by Kerr of Charles II establishing today’s Army Commonwealth army. -

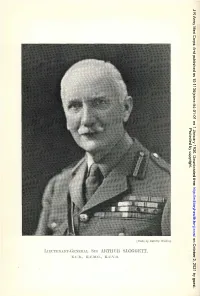

Lmc'renakt-Geciehal SIR Artiluh SLOGGETT, K .N.B., K.C.1-J.G., K.E.V.O

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-54-01-01 on 1 January 1930. Downloaded from Protected by copyright. http://militaryhealth.bmj.com/ on October 2, 2021 by guest. [Photo hy Dorcth?/ WtldiJlg LmC'rENAKT-GECiEHAL SIR ARTIlUH SLOGGETT, K .n.B., K.C.1-J.G., K.e.v.o. J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-54-01-01 on 1 January 1930. Downloaded from VOL. LIV. JANUARY, 1930. No. 1. Authors are alone responsible for the statements made and the opinions expressed in their papers. ~tlurnal of tb' ~bituar\? LIEUTENANT-GENERAL SIR ARTHUR SLOGGETT, K.C.B., Protected by copyright. K.C.M.G., K.C.V.O. SIR ARl'HUR SLOGGEl'l' was the son of Inspector-General W. H. Sloggett, R.N., and was born at Stoke Damerel, Devon, on November 24, 1857. He was educated' at King's College, London, of which he was subsequently elected a Fellow. He obtained the M.R.C.S.England and L.R.C.P.Edinburgh in 1880, and on February 5, 1881, was commissioned as Surgeon in the Medical Staff. In his batch were several men who afterwards attained distinction as administrators, the most eminent among them being the late Sir William Babtie. Sir Arthur Sloggett will be chiefly remembered as a wise administrator, his savoir-faire, knowledge of the world and of men, enabled him to succeed where other men, though http://militaryhealth.bmj.com/ well versed in Regulations, would have failed. Sir Arthur saw much active service ana was senior medical officer with British troops in' the Dongola expedition, 1896; he was mentioned in dispatches, received the Egyptian medal with two clasps, the Order of the Osmanieh and was promoted Surgeon Lieutenant-Colonel. -

Raising Professional Confidence: the Influence of the Anglo-Boer War (1899 – 1902) on the Development and Recognition of Nursing As a Profession

Raising professional confidence: The influence of the Anglo-Boer War (1899 – 1902) on the development and recognition of nursing as a profession A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing in the Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences. 2013 Charlotte Dale School of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work 2 Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 Declaration ........................................................................................................................................................... 6 Copyright Statement ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................................... 8 The Author ............................................................................................................................................................ 9 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 10 Chapter One ........................................................................................................................................................ 17 Nursing, War and the late Nineteenth Century -

Deeds and Words in the Suffrage Military Hospital in Endell Street

Medical History, 2007, 51: 79–98 Deeds and Words in the Suffrage Military Hospital in Endell Street JENNIAN F GEDDES* Introduction Shortly after war broke out in 1914 Dr Flora Murray and Dr Louisa Garrett Anderson, two former members of the Women’s Social and Political Union, founded their own women’s hospital organization to care for soldiers wounded in the fighting. Experience in the suffrage movement had taught them what the likely reaction of the authorities would be to any offer of help from women doctors, so they applied directly to the French, who accepted their offer and assigned them a newly built hotel in Paris for their hospital. During the autumn and early winter of 1914 Murray and Anderson’s ‘‘Women’s Hospital Corps’’ successfully ran two military hospitals, in Paris and at Wimereux on the Channel coast, until January 1915, when casualties began to be evacuated to England in preference to being treated in France. In the interim, the War Office had received many favourable reports of the WHC’s achievements, with the result that at the beginning of 1915 the women were invited to return to England, and given the opportunity to run a large military hospital in the centre of London, under the Royal Army Medical Corps. This hospital, the Endell Street Military Hospital, was open from May 1915 to the end of 1919. Entirely staffed by women, and the only women’s unit run by militant suffragists, it was one of the most remarkable hospitals of the war.1 By any standards, the achievements of the WHC were astonishing. -

BRITISH MEDICAL Joutnal

SUPPLEME1:13NT TO THE BRITISH MEDICAL JOUtNAL. LONDON: SATURDAY, AUGUST 14TH, 1915. CONTENTS. PAGE WAR EMERGENCY COMMITTEE... ... 85 MEETINGS OF BRANCHES AND DIVISIONS ... 90 INSURANCE ACTS COMMITTEE... ... ... 87 BRITISH MEDICAL ASSOCIATION: FURTHER EXTRAORDINARY GENERAL MEETING ... .. ... ... ... 90 LOCAL MEDICAL AND PANEL COMMITTEES: NAVAL AND I[tlITARY APPOINTMENTS ... ... 90 Middlesex (Panel Committee) ... ... ... 88 VITAL STATISTICS ... ... .. 91 Coventry (Panel Committee) ... ... ... 89 .. ... 92 Liverpool (Panel Committee) ... ... ... ... 89 VACANCIES AND APPOINTHENTS Shropshire (Panel Committee ... ... ... 89 BIRTHS. HARRIAGES. AND DETaL-I ., . .. 92 CORRESPONDENCE ... ... 89 DIARY OF THE ASSOCIATION ... ... ., .. 92 to the best possible use; to deal with all nmatters affecting the medlical profession arising in conneRxion 'i'nt'tsb grttztat Asraz with the war; and to report to the Council. M71embers of Commnnittee. WAR EMERGENCY COMMITTEE. Sir Thomas Clifford Allbutt, K.C.B.. M$.D., F.R.S., Cambridge. Sir William Osler, Bt., M.D., F.R.S., Oxfor(l. IT lhas already been reported that the War Emergency Dr. A. E. Shipley, F.R.S., Master of Christ's Collegce, Committee appointed by the Representative Meeting on Cambridlge. July 23rd lhad at its meeting on July 30tlh elected Dr. T. Sir Alex. Ogston, K.CX.O., Aberdeen (Presidenzt, British Mledical Jenner Verrall chairnman, Dr. A. E. Slhipley, Master of Associattioni). Mr. E. B. Turner, F.R.C.S., London (Cha,iirmiiani of I?epresentatire Clhrist's College, Cambridge, and Mr. E. B. Turner, Chair- llMeetingls, Britishl Medical Association). nman of Representative Meetings, vice-clhairmen, and Mr. Dr. J. A. Macdonald, LL.D., Taunton (Chairmnan of Conne1cil, Bishop Harman and Dr. Alfred Cox, Medical Secretary of British Mlledical Associa tion). -

War Neurosurgery: Triumphs and Transportation

War Neurosurgery: Triumphs and Transportation The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hedley-Whyte, John, and Debra Milamed. 2020. "War Neurosurgery: Triumphs and Transportation." Ulster Medical Journal 89, no. 2: 103-109. Published Version https://www.ums.ac.uk/umj089/089(2)103.pdf Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37367066 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Ulster Med J 2020;89(2):103-110 Medical History WAR NEUROSURGERY: TRIUMPHS AND TRANSPORTATION John Hedley-Whyte, M.D., F.A.C.P., F.R.C.A. Debra R. Milamed, M.S. Key Words: Neurosurgery, Mentors, Air Evacuation, World War I, World War II INTRODUCTION HARVEY CUSHING AND THE FOUNDING OF THE PETER BENT BRIGHAM HOSPITAL In both World War I and World War II approximately seven percent of battle casualties were due to cranial injuries. The years before World War I saw medico-political struggles In1915 Harvey Cushing led a Harvard-financed hospital to on both sides of the Atlantic. Between 1902 and 1912 the Paris. Cushing and Colonel Andrew Fullerton of Queen’s Peter Bent Brigham Trustees had negotiated with President University Belfast with advances of much specialist surgery, Lowell of Harvard for the establishment of the Peter Bent whole blood and trained nurses nearer to the Front Line Brigham Hospital next door to the Harvard Medical School1. -

Documents Relating to Australian Army Medical

APPENDIX No. 2 DOCUMENTS RELATING TO AUSTRALIAN ARMY MEDICAL SERVICES OVERSEAS (i) CORRESPONDENCE RELATING TO IMPERIAL CO- OPERATION IN THE MEDICAL SERVICES Letter, datcd 4th SeptrtiaBcr, 1917, froin Lreirt.-Grrreral Sir Alfred Keogh, D.G., A.M.S., to ihc ad?rrittistratizte hcads of the Medical Scrziiccs of the Dotihioris (iiiarkcd “Secret mid Confrrlcntial”) :- “For some time the Directors of the Medical Services of Australia, Canada and New Zealand have been in communication with me on a subject which is, I consider, of such importance that I should put it forward whether or not the statements I have to make commend themselves. “I should premise, however, that many years ago I made an at- tempt to keep the Medical Services of the Dominions in touch with our own, because it was obvious that the newer services ought to mould themselves on ours-their destiny being to work with us. In the case of Australia this was effected by frequent communication of a personal nature between the Australian D.G. and myself. The former was then engaged in organising the Medical Service of Australia, and in all essential particulars it developed on lines similar to that of Great Britain. The connection with Canada was closer for we were able to secure that selected officers from that portion of the Dominions came to us for instructioii in Administration, and were given opportunities of seeing the organisation and its constituent parts from Hospitals up to the W.O. branches. The result was a development in Canada along lines similar to our own. The service in New Zealand was a new formation, but the attitude of the Authorities has been sufficiently dis- played by their demand that their Director of M.S. -

Medical Women at War, 1914-1918

Medical History, 1994, 38: 160-177. MEDICAL WOMEN AT WAR, 1914-1918 by LEAH LENEMAN * Women had a long and difficult struggle before they were allowed to obtain a medical education.' Even in 1914 the Royal Free was the only London teaching hospital to admit them and some universities (including Oxford and Cambridge) still held out against them. The cost of a medical education continued to be a major obstacle, but at least there were enough schools by then to ensure that British women who wanted and could afford one could get it. The difficulty was in finding residency posts after qualifying, in order to make a career in hospital medicine. Few posts were available outside the handful of all-women hospitals, and medical women were channelled away from the more prestigious specialities-notably general surgery-into those less highly regarded, like gynaecology and obstetrics, and into asylums, dispensaries, public health, and, of course, general practice.2 When war broke out in August 1914, the Association of Registered Medical Women expected that women doctors would be needed mostly for civilian work, realizing that "as a result of the departure of so many medical men to the front there will be vacancies at home which medical women may usefully fill".3 As early as February 1915 it was estimated that a sixth of all the medical men in Scotland had taken commissions in the RAMC. In April of that year it was reported that "there is hardly a resident post not open to a qualified woman if she cares to apply for it". -

Annual Report 1914

NATIONAL HEALTH INSURANCE. FIRST ANNUAL REPORT OF THE MEDICAL RESEARCH COMMITTEE, 1914–1915. Presented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of His Majesty. LONDON; PRINTED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE By HARRISON and SONS, 45–47, St Martin’s Lane, W.C., Printers in Ordinary To His Majesty To be purchased, either directly or through any Bookseller, from WYMAN and SONS, Limited, 29, Breams Buildings, Fetter Lane, E.C., and 28, Abingdon Street, S.W., and 54, St Mary Street, Cardiff; or H.M. stationery OFFICE (Scottish Branch), 23 Forth Street, Edinburgh ; or E.PONSONBY, Limited, 116, Grafton Street, Dublin ; or from the Agencies in the British Colonies and Dependencies, the United States of America and other Foreign Countries of T. FISHER UNWIN, Limited, London, W.C. [Cd. 8101] Price Threepence. NATIONAL HEALTH INSURANCE, MEDICAL RESEARCH COMMITTEE. The following publications relating to the work of the Medical Research Committee can be purchased, either directly or through any bookseller, from Wyman & Sons, Ltd., 29, Breams Buildings, Fetter Lane, E.C., 28, Abingdon Street, S.W., and 54, St. Mary Street, Cardiff; or H.M. Stationery Office (Scottish Branch), 23, Forth Street, Edinburgh; or E. Ponsonby, Ltd., 116, Grafton Street, Dublin; or from the Agencies in the British Colonies and Dependencies, the United States of America and other Foreign Countries of T. Fisher Unwin, Ltd., London, W.C. National Health Insurance (Medical Research Fund) Regulations, 1914. [S.R. & O., 1914, No. 418.] Price 1d., post free 1½d. Interim Report on the Work in connection with the War undertaken by the Medical Research Committee. -

Imperialmagazine36.Pdf

Spring/Summer 2011 THE MAGAZINE OF IMPERIAL COLLEGE LONDON WAR ZONE Where innovation is forged? GENERATING GENIUS The summer schools changing lives SPRAY ME Haute couture chemistry DAVID WARREN The maker of the black box spring/summer 2011 18 inside > issue 36 Staff • Editor-in-Chief: Tom Miller (Biology 1995) • Creative Director: Beth Elzer • Editor-at-Large and Features Editor: Natasha Martineau (MSc Science Communica- tion 1994) • Alumni Editor: Zoe Perkins • News Editor: Laura Gallagher • Sub Editor and Production: Saskia Daniel • Mailing and Subscriptions: Elizabeth Atkin • Contributors: Anna Codrea- Rado, Tanya Gubbay, 24 Behind the scenes Colin Smith, Simon Watts, LIQUID ASSET Katie Weeks Civil engineers simulate the ocean in a wave basin The magazine for Imperial’s 12 friends, supporters and alumni, 26 Going public including former students of OPEN AIR LABS Imperial College London, the Nearly half a million citizen former Charing Cross and West- 3 Rector’s welcome 18 Picture this scientists sign up to help minster Medical School, Royal SPRAY-ON SCIENCE monitor urban and rural Postgraduate Medical School, 4 Inbox Science goes out in style as environments St Mary’s Hospital Medical Editorial and contributors spray-on technology goes School and Wye College. from lab to catwalk and 28 Travel 5 In brief chemical engineering meets INTO AFRICA Published twice a year by the Spotlight on recent events haute couture Beate Kampmann’s open lab Communications and Develop- and discoveries straddles nearly 3,000 miles ment Division. imperialmagazine 20 Feature from London to the Gambia @imperial.ac.uk 10 Product pipeline TECHNOLOGIES OF ATTENTION TO DETAIL WAR AND PEACE 29 Alter ego Subscriptions Spin-out technologies for New thinking from David LIGHT FANTASTIC If you would like to subscribe to seeing in new ways Edgerton reassesses the Theoretical physicist Imperial magazine please email relationship between war and Martin McCall puts in some imperialmagazine@imperial. -

Record-Keeping Practices in World War 1 in Relation to The

RECORD-KEEPING PRACTICES IN WORLD WAR I IN RELATION TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN BUREAUCRACY IN GREAT BRITAIN AND CANADA. A STUDY OF GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS AND OF THE ROYAL ARMY MEDICAL CORPS AND THE CANADIAN ARMY MEDICAL CORPS Brian McCullough Owens (University College London) Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London 1998 ProQuest Number: U642048 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642048 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DEDICATION Thanks are extended to many individuals who supported me as I conducted research, thought and wrote this thesis. Most notably are my supervisors, Jane E. Sayers and Virginia Berridge. Other individuals who have provided support have been Leslie Howsam, Heather Maclvor and Karen Marrero, College of Arts and Human Sciences, University of Windsor, Windsor, Canada; Claude Roberto, Provincial Archives of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada; and Laura Hamson-Hoyano, Faculty of Law, University of Bristol. I wish to thank the Trustees and Staff of the London Goodenough Trust for providing me with accommodation and a lively, intellectual and supportive community in central London.