(Pp. 105-12) in That Same Chapter Was an Exceptional Synthesis of How

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcasting Canada's War: How the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Reported the Second World War

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2017 Broadcasting Canada's War: How the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Reported the Second World War Sweazey, Connor Sweazey, C. (2017). Broadcasting Canada's War: How the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Reported the Second World War (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/25173 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/3759 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Broadcasting Canada's War: How the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Reported the Second World War by Connor Sweazey A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA APRIL, 2017 © Connor Sweazey 2017 Abstract Public Canadian radio was at the height of its influence during the Second World War. Reacting to the medium’s growing significance, members of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) accepted that they had a wartime responsibility to maintain civilian morale. The CBC thus unequivocally supported the national cause throughout all levels of its organization. Its senior administrations and programmers directed the CBC’s efforts to aid the Canadian war effort. -

105Th American Assembly on "U.S.-Canada

The 105th American Assembly ENEWING THE U. S. ~ Canada R ELATIONSHIP The American Assembly February 3–6, 2005 475 Riverside Drive, Suite 456 Arden House New York, New York, 10115 Harriman, New York Telephone: 212-870-3500 Fax: 212-870-3555 E-mail: [email protected] www.americanassembly.org Canada Institute Canadian Institute The Woodrow Wilson CANADIAN INSTITUT INSTITUTE OF CANADIEN DES of International Affairs International Center for Scholars INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRES AFFAIRS INTERNATIONALES 205 Richmond Street West One Woodrow Wilson Plaza Suite 302 1300 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. CIIA/ICAI Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5V 1V3 Washington, D.C. 20004-3027 Telephone: 416-977-9000 Telephone: 202-691-4270 Fax: 416-977-7521 Fax: 202-691-4001 www.ciia.org www.wilsoncenter.org/canada/ PREFACE On February 3, 2005, seventy women and men from the United States and Canada including government officials, representatives from business, labor, law, nonprofit organizations, academia, and the media gathered at Arden House in Harriman, New York for the 105th American Assembly entitled “U.S.-Canada Relations.” Assemblies had been sponsored on this topic in 1964 and 1984, and this third Assembly on bilateral relations was co-sponsored by the Canada Institute of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, the Canadian Institute for International Affairs (CIIA), and The American Assembly of Columbia University. The participants, representing a range of views, backgrounds, and interests, met for three days in small groups for intensive, structured discussions to examine the concerns and challenges of the binational relationship. This Assembly was co-chaired by Allan Gotlieb, former Canadian ambassador to the United States, former under secretary of state for External Affairs, and senior advisor at Stikeman Elliot LLP in Toronto and James Blanchard, former U.S. -

War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada's Military, 1952-1992 by Mallory

War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada’s Military, 19521992 by Mallory Schwartz Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in History Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Mallory Schwartz, Ottawa, Canada, 2014 ii Abstract War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada‘s Military, 19521992 Author: Mallory Schwartz Supervisor: Jeffrey A. Keshen From the earliest days of English-language Canadian Broadcasting Corporation television (CBC-TV), the military has been regularly featured on the news, public affairs, documentary, and drama programs. Little has been done to study these programs, despite calls for more research and many decades of work on the methods for the historical analysis of television. In addressing this gap, this thesis explores: how media representations of the military on CBC-TV (commemorative, history, public affairs and news programs) changed over time; what accounted for those changes; what they revealed about CBC-TV; and what they suggested about the way the military and its relationship with CBC-TV evolved. Through a material culture analysis of 245 programs/series about the Canadian military, veterans and defence issues that aired on CBC-TV over a 40-year period, beginning with its establishment in 1952, this thesis argues that the conditions surrounding each production were affected by a variety of factors, namely: (1) technology; (2) foreign broadcasters; (3) foreign sources of news; (4) the influence -

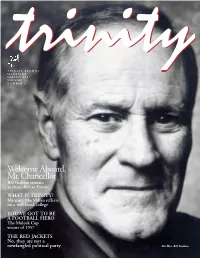

Welcome Aboard, Mr.Chancellor

17915 Trinity 4/25/07 2:09 PM Page 1 TRINITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE SPRING 2007 VOLUME 44 NUMBER 2 Welcome Aboard, Mr.Chancellor Bill Graham returns, as chancellor, to Trinity WHAT IS TRINITY? Margaret MacMillan reflects on a well-loved college YOU’VE GOT TO BE A FOOTBALL HERO The Mulock Cup victors of 1957 THE RED JACKETS No, they are not a newfangled political party The Hon. Bill Graham 17915 Trinity 4/25/07 2:09 PM Page 2 FromtheProvost The Last Word In her final column as Provost, Margaret MacMillan takes her leave with a fervent ‘Thank you, all’ hen I became Provost of this college five years not mean slavishly keeping every tradition, but picking out what was ago, I discovered all sorts of unexpected duties, important in what we inherited and discarding what was not. Estab- such as the long flower bed along Hoskin lished ways of doing things should never become a straitjacket. In W Avenue. When Bill Chisholm, then the build- my view, Trinity’s key traditions are its openness to difference, ing manager, told me on a cold January day that the Provost whether in ideas or people, its generous admiration for achievement always chose the plants, I did the only sensible thing and called in all fields, its tolerance, and its respect for the rule of law. my mother. She has looked after it ever since, with the results that I have made some changes while I have been here. Perhaps the so many of you have admired every summer. I also learned that I ones I feel proudest of are creating a single post of Dean of Students had to write this letter three times a year for the magazine. -

NAHLAH AYED FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT | the NATIONAL a Beginning, a Middle and an End: Canadian Foreign Reportage Examined

School of Journalism 34th Annual James M. Minifie Lecture NAHLAH AYED FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT | THE NATIONAL A beginning, a middle and an end: Canadian foreign reportage examined. March 12, 2014 QUESTION AUTHORITY Study Journalism at the University of Regina Learn to craft stories for all forms of media. Stories that engage. Stories that inform. Stories that empower the public. Stories that build a stronger democracy. www.uregina.ca/arts/journalism • [email protected] • 306-585-4420 A beginning, a middle and an end: Canadian foreign reportage examined. It’s a real honour to be here in Regina and especially to give the Minifie lecture. James M. Minifie embodied the best of Canadian foreign journalism. He was an early integrator who filed for both radio and TV and I’m sure would have also filed for online had it existed. The story of my coming to give this lecture is a little bit like the job that we do, a little like doing foreign correspondence. Just like foreign correspondence, every obstacle that could possibly be thrown in my way happened! I felt like I was being tested – the way we are with every single story we file. Even the very last leg of this journey, coming from Toronto just a few hours ago, I barely made it out. It was wet snow and a huge lineup of planes being de- iced. I couldn’t believe we made it out. So, just like every story we file, the object, as painful as it can be, is to make deadline – no matter what. The idea is that an imperfect but accurate and complete story on the air is better than no story. -

Kingston Frontenac Public Library Meet Your Library Board 2015-2018

Kingston Frontenac Public Library Meet your Library Board 2015-2018 Barbara Aitken Education: B. A. (Honours) History and Political Studies, Queen's University B.L.S., University of Toronto Experience: Queen’s University, Public Services Librarian, 1962-1965; 1987-2002 (took early retirement); KPL Head of Reference, 1966-1969 Musee de l’homme, Palais de Chaillot, Paris, France, 1965 UNESCO, Education Division, Documentation, Paris, France, 1966 Professional Affiliation: Certified Genealogical Record Searcher, 1979-2005; Certified Genealogist, 2005- 2014, Board for the Certification of Genealogists, Washington, D.C. Association of Professional Genealogists, member Awards: Top 50 in 50 – honoured as an Ontario Genealogical Society (OGS) volunteer who has made an outstanding contribution to a branch, as nominated by Kingston Branch OGS, in the 50th anniversary year of OGS, 2011 OGS Citation of Recognition for contributions to The Society in furthering genealogical research in Ontario, 2002, one of two awarded in 2002 Volunteer Activities: Ontario Genealogical Society Kingston Branch Retirees` Association of Queen`s Council Library Connections: Frontenac County Public Library Board Trustee, 1970-1972, 1973-1979 (Kingston Township representative) Lake Ontario Regional Library Board Trustee, representative. from FCPLB, 1973- 1979 Library patron of KPL and KFPL since 1962 Friends of KFPL member A city-appointed member of the KFPL Board since 2004, including five years` service on the Calvin Park Building Committee Why you applied to be on the Library Board: I volunteered in order to help contribute to this vital community service that seeks to provide the information, education and leisure needs of our citizens in Kingston and throughout Frontenac County. -

A Voice Behind the Headlines: the Public Relations of the Canadian Jewish Congress

A Voice Behind the Headlines: The Public Relations of the Canadian Jewish Congress during World War II by Nathan Lucky B.A., Hons. The University of British Columbia (Okanagan), 2018 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2021 © Nathan Lucky, 2021 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the thesis entitled: A Voice Behind the Headlines: The Public Relations of the Canadian Jewish Congress during World War II submitted by Nathan Lucky in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Examining Committee: Heidi Tworek, Associate Professor, Department of History, UBC Supervisor Richard Menkis, Associate Professor, Department of History, UBC Supervisory Committee Member Michel Ducharme, Associate Professor, Department of History, UBC Additional Examiner ii Abstract This thesis examines the public relations campaigns of the Canadian Jewish Congress (CJC) during World War II within the framework of agenda setting theory. As the voice of Canadian Jewry, the CJC implemented a sophisticated public relations strategy that brought attention to their causes in the non-Jewish press. From September 1939, the CJC capitalized on the patriotic atmosphere fostered by the war and the Canadian government. In a data-driven publicity campaign that would last the war, the CJC systematically both encouraged and tracked war efforts among Canadian Jews to fuel patriotic stories about Jews that improved their reputation. After it became clear in the summer of 1942 that the Nazis had begun exterminating Jews in Occupied Europe, the CJC started an awareness campaign in the non-Jewish press. -

NAC, the News, and the Neoliberal State, 1984-1993

NAC, the News, and the Neoliberal State, 1984-1993 Samantha C. Thrift Department of Art History and Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal August 2009 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies. © Samantha C. Thrift 2009 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-66542-8 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-66542-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

The Canadian Army, Public Relations, and War News During the Second World War

The Information Front: The Canadian Army, Public Relations, and War News during the Second World War By Timothy John Balzer B.R.E., Northwest Baptist Theological College, 1989 B.A., Trinity Western University, 1991 M.R.E., Trinity Western University, 1993 M.A., University of Victoria, 2004 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History © Timothy John Balzer, 2009 University of Victoria All Rights Reserved. This Dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part by photocopying, or other means without the permission of the author. ISBN: 978-0-494-52939-3 ii The Information Front: The Canadian Army, Public Relations, and War News during the Second World War By Timothy John Balzer B.R.E., Northwest Baptist Theological College, 1989 B.A., Trinity Western University, 1991 M.R.E., Trinity Western University, 1993 M.A., University of Victoria, 2003 Supervisory Committee Dr. David Zimmerman, Supervisor (Department of History) Dr. Patricia E. Roy, Departmental Member (Professor Emeritus, Department of History) Dr. A. Perry Biddiscombe, Departmental Member (Department of History) Professor David Leach, Outside Member (Department of Writing) iii Supervisory Committee Dr. David Zimmerman, Supervisor (Department of History) Dr. Patricia A. Roy, Departmental Member (Professor Emeritus, Department of History) Dr. A. Perry Biddiscombe, Departmental Member (Department of History) Professor David Leach, Outside Member (Department of Writing) Abstract War news and public relations (PR) was a critical consideration for the Canadian Army during the Second World War. The Canadian Army developed its PR apparatus from nothing to an efficient publicity machine by war’s end, despite a series of growing pains. -

The Fatal Englishman: Three Short Lives Free

FREE THE FATAL ENGLISHMAN: THREE SHORT LIVES PDF Sebastian Faulks | 352 pages | 25 Feb 1997 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099518013 | English | London, United Kingdom The fragile Englishmen | Jane Gardam | The Guardian Look Inside. In The Fatal Englishmanhis first work of nonfiction, Sebastian Faulks explores the lives of three remarkable men. Each had the seeds of greatness; each was a beacon to his generation and left something of value behind; yet each one died tragically young. Christopher Wood, only twenty-nine when he killed himself, was a painter who lived most of his short life in The Fatal Englishman: Three Short Lives beau monde of s Paris, where his charm, good looks, and the dissolute life that followed them sometimes frustrated his ambition and achievement as an artist. Jeremy Wolfenden, hailed by his contemporaries as the brightest Englishman of his generation, rejected the call of academia to become a hack journalist in Cold War Moscow. A spy, alcoholic, and open homosexual at a time when such activity was still illegal, he died at the age of thirty- one, a victim of his own recklessness and of the peculiar pressures of his time. Through the lives of these doomed young men, Faulks paints an oblique portrait of English society as it changed in the twentieth century, from the Victorian era to the modern world. Sebastian Faulks worked as a journalist for 14 years before taking up writing full-time in Superbly portrayed. When you buy a book, we donate a book. Sign in. The Best Books of So Far. Read An Excerpt. Mar 12, ISBN Add to Cart. -

By David Halton Lisa Jane De Gara

Canadian Military History Volume 26 | Issue 1 Article 3 3-7-2017 "Dispatches from the Front: The Life of Matthew Halton, Canada’s Voice at War (Book Review)" by David Halton Lisa Jane de Gara Recommended Citation de Gara, Lisa Jane () ""Dispatches from the Front: The Life of Matthew Halton, Canada’s Voice at War (Book Review)" by David Halton," Canadian Military History: Vol. 26 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh/vol26/iss1/3 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. de Gara: Dispatches from the Front (Book Review) CANADIAN MILITARY HISTORY 5 Matthew Halton. Dispatches from the Front: The Life of Matthew Halton, Canada’s Voice at War. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2014. Pp. 352. Matthew Halton served as a Foreign Correspondent for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) during the Second World War, and his broadcasts serve as a vital record for both Canada’s role in the conflict and the willingness of the CBC to acknowledge the brutality of conflict to its domestic audiences. Arguably once known more widely than Billy Bishop (p. 2), Halton’s prominence in the Canadian canon dwindled in the intervening decades. Dispatches from the Front, as an accessible mass-market tome, hopes to assert Halton as a hero worthy of the Canadian canon. The efforts to make a hero of a mostly-forgotten journalist are not assumed. -

Kingston Frontenac Public Library Meet Your Library Board 2015-2018

Kingston Frontenac Public Library Meet your Library Board 2015-2018 Barbara Aitken Education: B. A. (Honours) History and Political Studies, Queen's University B.L.S., University of Toronto Experience: Queen’s University, Public Services Librarian, 1962-1965; 1987-2002 (took early retirement); KPL Head of Reference, 1966-1969 Musee de l’homme, Palais de Chaillot, Paris, France, 1965 UNESCO, Education Division, Documentation, Paris, France, 1966 Professional Affiliation: Certified Genealogical Record Searcher, 1979-2005; Certified Genealogist, 2005- 2014, Board for the Certification of Genealogists, Washington, D.C. Association of Professional Genealogists, member Awards: Top 50 in 50 – honoured as an Ontario Genealogical Society (OGS) volunteer who has made an outstanding contribution to a branch, as nominated by Kingston Branch OGS, in the 50th anniversary year of OGS, 2011 OGS Citation of Recognition for contributions to The Society in furthering genealogical research in Ontario, 2002, one of two awarded in 2002 Volunteer Activities: Ontario Genealogical Society Kingston Branch Retirees` Association of Queen`s Council Library Connections: Frontenac County Public Library Board Trustee, 1970-1972, 1973-1979 (Kingston Township representative) Lake Ontario Regional Library Board Trustee, representative. from FCPLB, 1973- 1979 Library patron of KPL and KFPL since 1962 Friends of KFPL member A city-appointed member of the KFPL Board since 2004, including five years` service on the Calvin Park Building Committee Why you applied to be on the Library Board: I volunteered in order to help contribute to this vital community service that seeks to provide the information, education and leisure needs of our citizens in Kingston and throughout Frontenac County.