Popular Public Shaming and Pseudonymous Plaintiffs Jayne S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking Intellectual Property Into Their Own Hands

Taking Intellectual Property into Their Own Hands Amy Adler* & Jeanne C. Fromer** When we think about people seeking relief for infringement of their intellectual property rights under copyright and trademark laws, we typically assume they will operate within an overtly legal scheme. By contrast, creators of works that lie outside the subject matter, or at least outside the heartland, of intellectual property law often remedy copying of their works by asserting extralegal norms within their own tight-knit communities. In recent years, however, there has been a growing third category of relief-seekers: those taking intellectual property into their own hands, seeking relief outside the legal system for copying of works that fall well within the heartland of copyright or trademark laws, such as visual art, music, and fashion. They exercise intellectual property self-help in a constellation of ways. Most frequently, they use shaming, principally through social media or a similar platform, to call out perceived misappropriations. Other times, they reappropriate perceived misappropriations, therein generating new creative works. This Article identifies, illustrates, and analyzes this phenomenon using a diverse array of recent examples. Aggrieved creators can use self-help of the sorts we describe to accomplish much of what they hope to derive from successful infringement litigation: collect monetary damages, stop the appropriation, insist on attribution of their work, and correct potential misattributions of a misappropriation. We evaluate the benefits and demerits of intellectual property self-help as compared with more traditional intellectual property enforcement. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38KP7TR8W Copyright © 2019 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Inc. -

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Ohio State University Alexandra Mary Jenkins, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Jared Gardner, Advisor Sean O’Sullivan Robyn Warhol Copyright by Alexandra Mary Jenkins 2014 Abstract Feminist activism in the United States and Europe during the 1960s and 1970s harnessed radical social thought and used innovative expressive forms in order to disrupt the “grand perspective” espoused by men in every field (Adorno 206). Feminist student activists often put their own female bodies on display to disrupt the disembodied “objective” thinking that still seemed to dominate the academy. The philosopher Theodor Adorno responded to one such action, the “bared breasts incident,” carried out by his radical students in Germany in 1969, in an essay, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis.” In that essay, he defends himself against the students’ claim that he proved his lack of relevance to contemporary students when he failed to respond to the spectacle of their liberated bodies. He acknowledged that the protest movements seemed to offer thoughtful people a way “out of their self-isolation,” but ultimately, to replace philosophy with bodily spectacle would mean to miss the “infinitely progressive aspect of the separation of theory and praxis” (259, 266). Lisa Yun Lee argues that this separation continues to animate contemporary feminist debates, and that it is worth returning to Adorno’s reasoning, if we wish to understand women’s particular modes of theoretical ii insight in conversation with “grand perspectives” on cultural theory in the twenty-first century. -

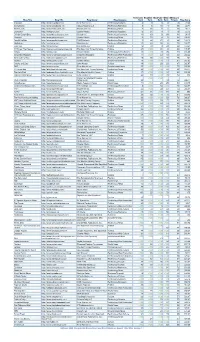

Blog Title Blog URL Blog Owner Blog Category Technorati Rank

Technorati Bloglines BlogPulse Wikio SEOmoz’s Blog Title Blog URL Blog Owner Blog Category Rank Rank Rank Rank Trifecta Blog Score Engadget http://www.engadget.com Time Warner Inc. Technology/Gadgets 4 3 6 2 78 19.23 Boing Boing http://www.boingboing.net Happy Mutants LLC Technology/Marketing 5 6 15 4 89 33.71 TechCrunch http://www.techcrunch.com TechCrunch Inc. Technology/News 2 27 2 1 76 42.11 Lifehacker http://lifehacker.com Gawker Media Technology/Gadgets 6 21 9 7 78 55.13 Official Google Blog http://googleblog.blogspot.com Google Inc. Technology/Corporate 14 10 3 38 94 69.15 Gizmodo http://www.gizmodo.com/ Gawker Media Technology/News 3 79 4 3 65 136.92 ReadWriteWeb http://www.readwriteweb.com RWW Network Technology/Marketing 9 56 21 5 64 142.19 Mashable http://mashable.com Mashable Inc. Technology/Marketing 10 65 36 6 73 160.27 Daily Kos http://dailykos.com/ Kos Media, LLC Politics 12 59 8 24 63 163.49 NYTimes: The Caucus http://thecaucus.blogs.nytimes.com The New York Times Company Politics 27 >100 31 8 93 179.57 Kotaku http://kotaku.com Gawker Media Technology/Video Games 19 >100 19 28 77 216.88 Smashing Magazine http://www.smashingmagazine.com Smashing Magazine Technology/Web Production 11 >100 40 18 60 283.33 Seth Godin's Blog http://sethgodin.typepad.com Seth Godin Technology/Marketing 15 68 >100 29 75 284 Gawker http://www.gawker.com/ Gawker Media Entertainment News 16 >100 >100 15 81 287.65 Crooks and Liars http://www.crooksandliars.com John Amato Politics 49 >100 33 22 67 305.97 TMZ http://www.tmz.com Time Warner Inc. -

Facebook, Social Media Privacy, and the Use and Abuse of Data

S. HRG. 115–683 FACEBOOK, SOCIAL MEDIA PRIVACY, AND THE USE AND ABUSE OF DATA JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE AND THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 10, 2018 Serial No. J–115–40 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( Available online: http://www.govinfo.gov VerDate Nov 24 2008 09:24 Nov 08, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 S:\GPO\DOCS\37801.TXT JACKIE FACEBOOK, SOCIAL MEDIA PRIVACY, AND THE USE AND ABUSE OF DATA VerDate Nov 24 2008 09:24 Nov 08, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 S:\GPO\DOCS\37801.TXT JACKIE S. HRG. 115–683 FACEBOOK, SOCIAL MEDIA PRIVACY, AND THE USE AND ABUSE OF DATA JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE AND THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 10, 2018 Serial No. J–115–40 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( Available online: http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 37–801 PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Nov 24 2008 09:24 Nov 08, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\DOCS\37801.TXT JACKIE SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JOHN THUNE, South Dakota, Chairman ROGER WICKER, Mississippi BILL NELSON, Florida, Ranking ROY BLUNT, Missouri MARIA -

Congressman Pete Stark Acknowledges Reason Rally

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Michelle Blackley Phone: (716) 636-4869, ext. 218 E-mail: [email protected] Stark Acknowledges the Reason Rally The US Congressman will contribute to the Rally March 24, in Washington, DC Washington, DC–January 26, 2012–Today, Rep. Pete Stark (D-CA) has agreed to prove a video testimonial at the Reason Rally, March 24, 2012 on the National Mall in Washington, DC. Stark is the first openly atheist member of Congress, as announced by the Secular Coalition for America (SCA). Stark acknowledged that he is an atheist in response to an SCA questionnaire sent to public officials in January 2007. During that same year he reaffirmed that he is an atheist by making a public announcement in front of the Humanist Chaplaincy at Harvard, the Harvard Law School Heathen Society, and various other atheist, agnostic, secular, humanist, and nonreligious groups. The American Humanist Association (AHA) named him their 2008 Humanist of the Year, and he now serves on the AHA Advisory Board. “Unfortunately he can’t make it personally but this endorsement from Mr. Stark is a great addition to the Reason Rally,” organizer and chair David Silverman said. The Reason Rally, a nationwide celebration sponsored by the top secular organizations in the United States, will be held from 10 AM to 5 PM. With the intent to unify, energize, and embolden secular people nationwide, the Reason Rally is a FREE event that will combat negative stereotypes about nonreligious Americans. It is slated to be the largest secular event in World history. Leaders of the secular movement, including a FREE concert by Bad Religion, will fill the rally with music, comedy and reason. -

Communication & Media Studies

COMMUNICATION & MEDIA STUDIES BOOKS FOR COURSES 2011 PENGUIN GROUP (USA) Here is a great selection of Penguin Group (usa)’s Communications & Media Studies titles. Click on the 13-digit ISBN to get more information on each title. n Examination and personal copy forms are available at the back of the catalog. n For personal service, adoption assistance, and complimentary exam copies, sign up for our College Faculty Information Service at www.penguin.com/facinfo 2 COMMUNICaTION & MEDIa STUDIES 2011 CONTENTS Jane McGonigal Mass Communication ................... 3 f REality IS Broken Why Games Make Us Better and Media and Culture .............................4 How They Can Change the World Environment ......................................9 Drawing on positive psychology, cognitive sci- ence, and sociology, Reality Is Broken uncov- Decision-Making ............................... 11 ers how game designers have hit on core truths about what makes us happy and uti- lized these discoveries to astonishing effect in Technology & virtual environments. social media ...................................13 See page 4 Children & Technology ....................15 Journalism ..................................... 16 Food Studies ....................................18 Clay Shirky Government & f CognitivE Surplus Public affairs Reporting ................. 19 Creativity and Generosity Writing for the Media .....................22 in a Connected age Reveals how new technology is changing us from consumers to collaborators, unleashing Radio, TElEvision, a torrent -

Python: XML, Sockets, Servers

CS107 Handout 37 Spring 2008 May 30, 2008 Python: XML, Sockets, Servers XML is an overwhelmingly popular data exchange format, because it’s human-readable and easily digested by software. Python has excellent support for XML, as it provides both SAX (Simple API for XML) and DOM (Document Object Model) parsers via xml.sax, xml.dom, and xml.dom.minidom modules. SAX parsers are event-driven parsers that prompt certain methods in a user- supplied object to be invoked every time some significant XML fragment is read. DOM parsers are object-based parsers than build in-memory representations of entire XML documents. Python SAX: Event Driven Parsing SAX parsers are popular when the XML documents are large, provided the program can get what it needs from the XML document in a single pass. SAX parsers are stream- based, and regardless of XML document length, SAX parsers keep only a constant amount of the XML in memory at any given time. Typically, SAX parsers read character by character, from beginning to end with no ability to rewind or backtrack. It accumulates the stream of characters building the next XML fragment, where the fragment is either a start element tag, an end element tag, or character data content. As it reads the end of one fragment, it fires off the appropriate method in some handler class to handle the XML fragment. For instance, consider the ordered stream of characters that might be a some web server’s response to an http request: <point>Here’s the coordinate.<long>112.4</long><lat>-45.8</lat></point> In the above example, you’d expect events to be fired as the parser pulls in each of the characters are the tips of each arrow. -

Build “Customer Equity.” They Define a Firm’S Customer Equity As the Total Discounted Lifetime Value of All of Its Customers

9780071458290-Ch-06 10/18/07 3:41 PM Page 115 CHAPTER 6 building customer relationships It has been called the decade of the customer, the customer millennium, and virtually every name that can incorporate “customer” within. There’s nothing new about businesses focusing on customers or wanting to be customer-centered. However, in today’s marketplace just saying an enterprise is “customer-centric” is not enough. It is a promise that organizations must keep. The problem is that most organizations still fall short of this goal. This chapter will address customer management and the variety of techniques used in customer relationship building, nurturing, loyalty, retention, and reactivation. These include Customer Relationship Management (CRM), Customer Performance Management (CPM), Customer Experience Management (CEM), and customer win-back. The objective of these techniques is to help organizations coax the greatest value from their customers. While the strategies are different, all of these methods use the tools and techniques of direct marketing in their execution. What is “Customer-Centric”? There is a clear definition of “customer-centric.” To be customer-centric, an organization must have customers at the center of its business. Many organizations are sales-focused and not marketing-oriented. Many enterprises that have a marketing focus are brand- or product-centric. Being a customer-centered organ- ization is much more complex than it appears. Enterprises can’t just decide to organize around customers. Today, it is often cus- tomers who dictate how an enterprise should be organized to better serve their needs. Customers want their needs met, to be cared for, and to be delighted. -

The Fashion Industry As a Slippery Discursive Site: Tracing the Lines of Flight Between Problem and Intervention

THE FASHION INDUSTRY AS A SLIPPERY DISCURSIVE SITE: TRACING THE LINES OF FLIGHT BETWEEN PROBLEM AND INTERVENTION Nadia K. Dawisha A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Patricia Parker Sarah Dempsey Steve May Michael Palm Neringa Klumbyte © 2016 Nadia K. Dawisha ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Nadia K. Dawisha: The Fashion Industry as a Slippery Discursive Site: Tracing the Lines of Flight Between Problem and Intervention (Under the direction of Dr. Patricia Parker) At the intersection of the glamorous façade of designer runway shows, such as those in Paris, Milan and New York, and the cheap prices at the local Walmart and Target, is the complicated, somewhat insidious “business” of the fashion industry. It is complicated because it both exploits and empowers, sometimes through the very same practices; it is insidious because its most exploitative practices are often hidden, reproduced, and sustained through a consumer culture in which we are all in some ways complicit. Since fashion’s inception, people and institutions have employed a myriad of discursive strategies to ignore and even justify their complicity in exploitative labor, environmental degradation, and neo-colonial practices. This dissertation identifies and analyzes five predicaments of fashion while locating the multiple interventions that engage various discursive spaces in the fashion industry. Ultimately, the analysis of discursive strategies by creatives, workers, organizers, and bloggers reveals the existence of agile interventions that are as nuanced as the problem, and that can engage with disciplinary power in all these complicated places. -

A Portrait of Fandom Women in The

DAUGHTERS OF THE DIGITAL: A PORTRAIT OF FANDOM WOMEN IN THE CONTEMPORARY INTERNET AGE ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors TutoriAl College Ohio University _______________________________________ In PArtiAl Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors TutoriAl College with the degree of Bachelor of Science in Journalism ______________________________________ by DelAney P. Murray April 2020 Murray 1 This thesis has been approved by The Honors TutoriAl College and the Department of Journalism __________________________ Dr. Eve Ng, AssociAte Professor, MediA Arts & Studies and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Thesis Adviser ___________________________ Dr. Bernhard Debatin Director of Studies, Journalism ___________________________ Dr. Donal Skinner DeAn, Honors TutoriAl College ___________________________ Murray 2 Abstract MediA fandom — defined here by the curation of fiction, art, “zines” (independently printed mAgazines) and other forms of mediA creAted by fans of various pop culture franchises — is a rich subculture mAinly led by women and other mArginalized groups that has attracted mAinstreAm mediA attention in the past decAde. However, journalistic coverage of mediA fandom cAn be misinformed and include condescending framing. In order to remedy negatively biAsed framing seen in journalistic reporting on fandom, I wrote my own long form feAture showing the modern stAte of FAndom based on the generation of lAte millenniAl women who engaged in fandom between the eArly age of the Internet and today. This piece is mAinly focused on the modern experiences of women in fandom spaces and how they balAnce a lifelong connection to fandom, professional and personal connections, and ongoing issues they experience within fandom. My study is also contextualized by my studies in the contemporary history of mediA fan culture in the Internet age, beginning in the 1990’s And to the present day. -

Case No. 16-11220 in the UNITED

Case: 16-11220 Document: 00513719015 Page: 1 Date Filed: 10/14/2016 Case No. 16-11220 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT AMERICAN HUMANIST ASSOCIATION; ISAIAH SMITH, Plaintiffs – Appellants v. BIRDVILLE INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT; JACK MCCARTY, in his individual and official capacity; JOE D. TOLBERT, in his individual and official capacity; BRAD GREENE, in his individual and official capacity; RICHARD DAVIS, in his individual and official capacity; RALPH KUNKEL, in his individual and official capacity; CARY HANCOCK, in his individual and official capacity; DOLORES WEBB, in her individual and official capacity, Defendants – Appellees On Appeal from the United States District Court, Northern District of Texas, Fort Worth Division BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE FREEDOM FROM RELIGION FOUNDATION, CENTER FOR INQUIRY, AMERICAN ATHEISTS, RICHARD DAWKINS FOUNDATION FOR REASON & SCIENCE, AND SECULAR COALITION FOR AMERICA IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS Samuel T. Grover Attorney for Amicus Curiae Freedom From Religion Foundation P.O. Box 750 Madison, WI 53701 608-256-8900 [email protected] Case: 16-11220 Document: 00513719015 Page: 2 Date Filed: 10/14/2016 Case No. 16-11220 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT AMERICAN HUMANIST ASSOCIATION; ISAIAH SMITH, Plaintiffs – Appellants v. BIRDVILLE INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al., Defendants – Appellees CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS The undersigned counsel of record certifies that the following listed persons and entities as described in the fourth sentence of Rule 28.2.1 have an interest in the outcome of this case. These representations are made in order that the judges of this Court may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal. -

Progressive Punitivism: Notes on the Use of Punitive Social Control to Advance Social Justice Ends

Buffalo Law Review Volume 68 Number 1 Article 4 1-1-2020 Progressive Punitivism: Notes on the Use of Punitive Social Control to Advance Social Justice Ends Hadar Aviram UC Hastings College of the Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview Part of the Criminal Procedure Commons, and the Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons Recommended Citation Hadar Aviram, Progressive Punitivism: Notes on the Use of Punitive Social Control to Advance Social Justice Ends, 68 Buff. L. Rev. 199 (2020). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol68/iss1/4 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Buffalo Law Review VOLUME 68 JANUARY 2020 NUMBER 1 Progressive Punitivism: Notes on the Use of Punitive Social Control to Advance Social Justice Ends HADAR AVIRAM† INTRODUCTION Paul Manafort, one of the most reviled men connected with the Russian involvement in Donald Trump’s ascent to power, was convicted of multiple white collar crimes related to his foreign activities.1 Newspapers reported that Manafort was to serve his sentence at the notorious Rikers Island prison in New York, in conditions of “isolation.”2 This announcement caused an eruption of schadenfreude on social media, which was countered by sobering remarks from †Thomas E. Miller ‘73 Professor of Law, UC Hastings College of the Law.