Biol 317 Lecture Notes – Week 5 Summary Rosids: Malvids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Note on Host Diversity of Criconemaspp

280 Pantnagar Journal of Research [Vol. 17(3), September-December, 2019] Short Communication A note on host diversity of Criconema spp. Y.S. RATHORE ICAR- Indian Institute of Pulses Research, Kanpur- 208 024 (U.P.) Key words: Criconema, host diversity, host range, Nematode Nematode species of the genus Criconema (Tylenchida: showed preference over monocots. Superrosids and Criconemitidae) are widely distributed and parasitize Superasterids were represented by a few host plants only. many plant species from very primitive orders to However, Magnoliids and Gymnosperms substantially advanced ones. They are migratory ectoparasites and feed contributed in the host range of this nematode species. on root tips or along more mature roots. Reports like Though Rosids revealed greater preference over Asterids, Rathore and Ali (2014) and Rathore (2017) reveal that the percent host families and orders were similar in number most nematode species prefer feeding on plants of certain as reflected by similar SAI values. The SAI value was taxonomic group (s). In the present study an attempt has slightly higher for monocots that indicate stronger affinity. been made to precisely trace the host plant affinity of The same was higher for gymnosperms (0.467) in twenty-five Criconema species feeding on diverse plant comparison to Magnolids (0.413) (Table 1). species. Host species of various Criconema species Perusal of taxonomic position of host species in Table 2 reported by Nemaplex (2018) and others in literature were revealed that 68 % of Criconema spp. were monophagous aligned with families and orders following the modern and strictly fed on one host species. Of these, 20 % from system of classification, i.e., APG IV system (2016). -

Full of Beans: a Study on the Alignment of Two Flowering Plants Classification Systems

Full of beans: a study on the alignment of two flowering plants classification systems Yi-Yun Cheng and Bertram Ludäscher School of Information Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA {yiyunyc2,ludaesch}@illinois.edu Abstract. Advancements in technologies such as DNA analysis have given rise to new ways in organizing organisms in biodiversity classification systems. In this paper, we examine the feasibility of aligning two classification systems for flowering plants using a logic-based, Region Connection Calculus (RCC-5) ap- proach. The older “Cronquist system” (1981) classifies plants using their mor- phological features, while the more recent Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV (APG IV) (2016) system classifies based on many new methods including ge- nome-level analysis. In our approach, we align pairwise concepts X and Y from two taxonomies using five basic set relations: congruence (X=Y), inclusion (X>Y), inverse inclusion (X<Y), overlap (X><Y), and disjointness (X!Y). With some of the RCC-5 relationships among the Fabaceae family (beans family) and the Sapindaceae family (maple family) uncertain, we anticipate that the merging of the two classification systems will lead to numerous merged solutions, so- called possible worlds. Our research demonstrates how logic-based alignment with ambiguities can lead to multiple merged solutions, which would not have been feasible when aligning taxonomies, classifications, or other knowledge or- ganization systems (KOS) manually. We believe that this work can introduce a novel approach for aligning KOS, where merged possible worlds can serve as a minimum viable product for engaging domain experts in the loop. Keywords: taxonomy alignment, KOS alignment, interoperability 1 Introduction With the advent of large-scale technologies and datasets, it has become increasingly difficult to organize information using a stable unitary classification scheme over time. -

Diversity in Host Preference of Rotylenchus Spp. Y.S

International Journal of Science, Environment ISSN 2278-3687 (O) and Technology, Vol. 7, No 5, 2018, 1786 – 1793 2277-663X (P) DIVERSITY IN HOST PREFERENCE OF ROTYLENCHUS SPP. Y.S. Rathore Principal Scientist (Retd.), Indian Institute of Pulses Research, Kanpur -208024 (U.P.) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Species of the genus Rotylenchus are ecto- or semi-endo parasites and feed on roots of their host plants. In the study it was found that 50% species of Rotylenchus were monophagous and mostly on plants in the clade Rosids followed by monocots, Asterids and gymnosperms. In general, Rosids and Asterids combined parasitized more than 50% host species followed by monocots. Though food preference was species specific but by and large woody plants were preferred from very primitive families like Magnoliaceae and Lauraceae to representatives of advanced families. Woody plants like pines and others made a substantial contribution in the host range of Rotylenchus. Maximum number of Rotylenchus species harboured plants in families Poaceae (monocots), Rosaceae (Rosids) and Oleaceae (Asterids) followed by Fabaceae, Fagaceae, Asteraceae and Pinaceae. It is, therefore, suggested that agricultural crops should be grown far away from wild vegetation and forest plantations. Keywords: Rotylenchus, Magnoliids, Rosids, Asterids, Gymnosperms, Host preference. INTRODUCTION Species of the genus Rotylenchus (Nematoda: Haplolaimidae) are migratory ectoparasites and browse on the surface of roots. The damage caused by them is usually limited to necrosis of penetrated cells (1). However, species with longer stylet penetrate to tissues more deeply and killing more cells and called as semi-endoparasites (2,3). The genus contains 97 nominal species which parasitize on a wide range of wild and cultivated plants worldwide (3). -

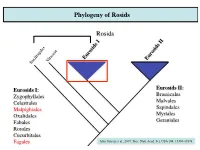

Phylogeny of Rosids! ! Rosids! !

Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Alnus - alders A. rubra A. rhombifolia A. incana ssp. tenuifolia Alnus - alders Nitrogen fixation - symbiotic with the nitrogen fixing bacteria Frankia Alnus rubra - red alder Alnus rhombifolia - white alder Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia - thinleaf alder Corylus cornuta - beaked hazel Carpinus caroliniana - American hornbeam Ostrya virginiana - eastern hophornbeam Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Fagaceae (Beech or Oak family) ! Fagaceae - 9 genera/900 species.! Trees or shrubs, mostly northern hemisphere, temperate region ! Leaves simple, alternate; often lobed, entire or serrate, deciduous -

ABSTRACTS 117 Systematics Section, BSA / ASPT / IOPB

Systematics Section, BSA / ASPT / IOPB 466 HARDY, CHRISTOPHER R.1,2*, JERROLD I DAVIS1, breeding system. This effectively reproductively isolates the species. ROBERT B. FADEN3, AND DENNIS W. STEVENSON1,2 Previous studies have provided extensive genetic, phylogenetic and 1Bailey Hortorium, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853; 2New York natural selection data which allow for a rare opportunity to now Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY 10458; 3Dept. of Botany, National study and interpret ontogenetic changes as sources of evolutionary Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, novelties in floral form. Three populations of M. cardinalis and four DC 20560 populations of M. lewisii (representing both described races) were studied from initiation of floral apex to anthesis using SEM and light Phylogenetics of Cochliostema, Geogenanthus, and microscopy. Allometric analyses were conducted on data derived an undescribed genus (Commelinaceae) using from floral organs. Sympatric populations of the species from morphology and DNA sequence data from 26S, 5S- Yosemite National Park were compared. Calyces of M. lewisii initi- NTS, rbcL, and trnL-F loci ate later than those of M. cardinalis relative to the inner whorls, and sepals are taller and more acute. Relative times of initiation of phylogenetic study was conducted on a group of three small petals, sepals and pistil are similar in both species. Petal shapes dif- genera of neotropical Commelinaceae that exhibit a variety fer between species throughout development. Corolla aperture of unusual floral morphologies and habits. Morphological A shape becomes dorso-ventrally narrow during development of M. characters and DNA sequence data from plastid (rbcL, trnL-F) and lewisii, and laterally narrow in M. -

Taxonomy 3110 Schedule

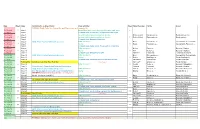

Date Week Class Assignments, Quizzes, Exams Class activities Week Talks (Tuesday) Family Group OVERALL PLAN: Talks Tue, Keying Tue and Thu, Lecture and Computer Fri Thu, Sep 08 1 Class 1 Intro if Rain (with reverse keying). Otherwise walk, press 1 Fri, Sep 09 Class 2 Computer Lab- Course info, on-paper exercises, login Tue, Sep 13 Class 3 no student talk, instructors explain the families Dmitry & Carol Nymphaeaceae Basal angiosperms Thu, Sep 15 2 Class 4 no student talk, instructors explain the families 2 Dmitry & Carol Ranunculaceae Basal eudicots Fri, Sep 16 Class 5 Computer Lab- Mesquite characters Tue, Sep 20 Class 6 QUIZ: 45 min Keying 1 plant and questions Talks and keying Bumo Caryophylaceae Caryophyllids-Caryophyllales Thu, Sep 22 3 Class 7 Keying 3 Maggie Polygonaceae Caryophyllids-Polygonales Fri, Sep 23 Class 8 Computer Lab- Setup and do the project on Characters Tue, Sep 27 Class 9 Talks and keying Melissa Fabaceae Eurosids I-Fabales Thu, Sep 29 4 Class 10 Keying 4 Nick Malvaceae Eurosids II-Malvales Fri, Sep 30 Class 11 Computer Lab- Mesquite and DNA Katherine Lamiaceae Euasterids I-Lamiales Tue, Oct 04 Class 12 QUIZ: 45 min Keying 1 plant and questions Talks and keying Brent Chenopodiaceae Caryophyllids-Caryophyllales Thu, Oct 06 5 Class 13 Keying 5 Robert Saxifragaceae Rosids-Saxifragales Fri, Oct 07 Class 14 Computer Lab - Molecular tools online, setup project Vanessa M Geraniaceae Rosids-Geraniales Tue, Oct 11 Thanksgiving Oct 10-11 break, W12 Mon, Th13 Tue :: no class :: Vanessa F Onagraceae Rosids-Myrtales Thu, Oct 13 -

A Global Assembly of Cotton Ests

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 3, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Resource A global assembly of cotton ESTs Joshua A. Udall,1 Jordan M. Swanson,1 Karl Haller,2 Ryan A. Rapp,1 Michael E. Sparks,1 Jamie Hatfield,2 Yeisoo Yu,3 Yingru Wu,4 Caitriona Dowd,4 Aladdin B. Arpat,5 Brad A. Sickler,5 Thea A. Wilkins,5 Jin Ying Guo,6 Xiao Ya Chen,6 Jodi Scheffler,7 Earl Taliercio,7 Ricky Turley,7 Helen McFadden,4 Paxton Payton,8 Natalya Klueva,9 Randell Allen,9 Deshui Zhang,10 Candace Haigler,10 Curtis Wilkerson,11 Jinfeng Suo,12 Stefan R. Schulze,13 Margaret L. Pierce,14 Margaret Essenberg,14 HyeRan Kim,3 Danny J. Llewellyn,4 Elizabeth S. Dennis,4 David Kudrna,3 Rod Wing,3 Andrew H. Paterson,13 Cari Soderlund,2 and Jonathan F. Wendel1,15 1Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Organismal Biology, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa 50011, USA; 2Arizona Genomics Computational Laboratory, BIO5 Institute, 3Arizona Genomics Institute, Department of Plant Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721, USA; 4CSIRO Plant Industry, Canberra City ACT 2601, Australia; 5Department of Plant Sciences, University of California–Davis, Davis, California 95616, USA; 6Institute of Plant Physiology and Ecology, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Shanghai, 200032, China; 7United States Department of Agriculture–Agricultural Research Service, Stoneville, Mississippi 38776, USA; 8United States Department of Agriculture–Agricultural Research Service, Lubbock, Texas 79415, USA; 9Department of Biology, Texas Tech University, -

Updated Angiosperm Family Tree for Analyzing Phylogenetic Diversity and Community Structure

Acta Botanica Brasilica - 31(2): 191-198. April-June 2017. doi: 10.1590/0102-33062016abb0306 Updated angiosperm family tree for analyzing phylogenetic diversity and community structure Markus Gastauer1,2* and João Augusto Alves Meira-Neto2 Received: August 19, 2016 Accepted: March 3, 2017 . ABSTRACT Th e computation of phylogenetic diversity and phylogenetic community structure demands an accurately calibrated, high-resolution phylogeny, which refl ects current knowledge regarding diversifi cation within the group of interest. Herein we present the angiosperm phylogeny R20160415.new, which is based on the topology proposed by the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV, a recently released compilation of angiosperm diversifi cation. R20160415.new is calibratable by diff erent sets of recently published estimates of mean node ages. Its application for the computation of phylogenetic diversity and/or phylogenetic community structure is straightforward and ensures the inclusion of up-to-date information in user specifi c applications, as long as users are familiar with the pitfalls of such hand- made supertrees. Keywords: angiosperm diversifi cation, APG IV, community tree calibration, megatrees, phylogenetic topology phylogeny comprising the entire taxonomic group under Introduction study (Gastauer & Meira-Neto 2013). Th e constant increase in knowledge about the phylogenetic The phylogenetic structure of a biological community relationships among taxa (e.g., Cox et al. 2014) requires regular determines whether species that coexist within a given revision of applied phylogenies in order to incorporate novel data community are more closely related than expected by chance, and is essential information for investigating and avoid out-dated information in analyses of phylogenetic community assembly rules (Kembel & Hubbell 2006; diversity and community structure. -

Saxifragaceae Sensu Lato (DNA Sequencing/Evolution/Systematics) DOUGLAS E

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 87, pp. 4640-4644, June 1990 Evolution rbcL sequence divergence and phylogenetic relationships in Saxifragaceae sensu lato (DNA sequencing/evolution/systematics) DOUGLAS E. SOLTISt, PAMELA S. SOLTISt, MICHAEL T. CLEGGt, AND MARY DURBINt tDepartment of Botany, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164; and tDepartment of Botany and Plant Sciences, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521 Communicated by R. W. Allard, March 19, 1990 (received for review January 29, 1990) ABSTRACT Phylogenetic relationships are often poorly quenced and analyses to date indicate that it is reliable for understood at higher taxonomic levels (family and above) phylogenetic analysis at higher taxonomic levels, (ii) rbcL is despite intensive morphological analysis. An excellent example a large gene [>1400 base pairs (bp)] that provides numerous is Saxifragaceae sensu lato, which represents one of the major characters (bp) for phylogenetic studies, and (iii) the rate of phylogenetic problems in angiosperms at higher taxonomic evolution of rbcL is appropriate for addressing questions of levels. As originally defined, the family is a heterogeneous angiosperm phylogeny at the familial level or higher. assemblage of herbaceous and woody taxa comprising 15 We used rbcL sequence data to analyze phylogenetic subfamilies. Although more recent classifications fundamen- relationships in a particularly problematic group-Engler's tally modified this scheme, little agreement exists regarding the (8) broadly defined family Saxifragaceae (Saxifragaceae circumscription, taxonomic rank, or relationships of these sensu lato). Based on morphological analyses, the group is subfamilies. The recurrent discrepancies in taxonomic treat- almost impossible to distinguish or characterize clearly and ments of the Saxifragaceae prompted an investigation of the taxonomic problems at higher power of chloroplast gene sequences to resolve phylogenetic represents one of the greatest relationships within this family and between the Saxifragaceae levels in the angiosperms (9, 10). -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Miao Sun Contact Information Plant Evolution and Biodiversity (PEB) Group Department of Biology – Ecoinformatics and Biodiversity, Aarhus University Ny Munkegade 116, Building 1535, Room 227, 8000 Aarhus C, Denmark Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Homepage: https://www.sunmiao.name Twitter: @Miao_the_Sun Education • 2009 ~ 2014, PhD in Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences • 2006 ~ 2009, Master of Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences • 2002 ~ 2006, Bachelor of Environmental Science, College of Resources and Environment, Beijing Forestry University • 2020.2 ~ 2020.8, Visiting scholar in Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Michigan • 2012.10 ~ 2013.1, Visiting scholar in Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida Positions • Postdoctoral Research Fellow (2019.10 ~ present) Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University Advisor: Dr. Wolf L. Eiserhardt • Postdoctoral Research Fellow (2016 ~ 2019.8) Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida Advisor: Dr. Pamela S. Soltis • Postdoctoral Research Fellow (2015 ~ 2016) Department of Biology, University of Florida Advisor: Dr. Douglas E. Soltis • Research Assistant (2014.07 ~ 2015.01) State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences Advisor: Dr. Zhiduan Chen 1 Research Interests A phylogenetic tree is a pivotal framework for solving fundamental issues in biology. For a long term, I have endeavored to build large -

Systematics and Biogeography of the Clusioid Clade (Malpighiales) Brad R

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Biological Sciences Faculty and Staff Research Biological Sciences January 2011 Systematics and Biogeography of the Clusioid Clade (Malpighiales) Brad R. Ruhfel Eastern Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/bio_fsresearch Part of the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Ruhfel, Brad R., "Systematics and Biogeography of the Clusioid Clade (Malpighiales)" (2011). Biological Sciences Faculty and Staff Research. Paper 3. http://encompass.eku.edu/bio_fsresearch/3 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Sciences Faculty and Staff Research by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARVARD UNIVERSITY Graduate School of Arts and Sciences DISSERTATION ACCEPTANCE CERTIFICATE The undersigned, appointed by the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology have examined a dissertation entitled Systematics and biogeography of the clusioid clade (Malpighiales) presented by Brad R. Ruhfel candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and hereby certify that it is worthy of acceptance. Signature Typed name: Prof. Charles C. Davis Signature ( ^^^M^ *-^£<& Typed name: Profy^ndrew I^4*ooll Signature / / l^'^ i •*" Typed name: Signature Typed name Signature ^ft/V ^VC^L • Typed name: Prof. Peter Sfe^cnS* Date: 29 April 2011 Systematics and biogeography of the clusioid clade (Malpighiales) A dissertation presented by Brad R. Ruhfel to The Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Biology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2011 UMI Number: 3462126 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Comparative Analysis of Gossypium and Vitis Genomes Indicates Genome Duplication Specific to the Gossypium Lineage

Genomics 97 (2011) 313–320 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Genomics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ygeno Comparative analysis of Gossypium and Vitis genomes indicates genome duplication specific to the Gossypium lineage Lifeng Lin a, Haibao Tang a, Rosana O. Compton a, Cornelia Lemke a, Lisa K. Rainville a, Xiyin Wang a,b, Junkang Rong a,1, Mukesh Kumar Rana a,c, Andrew H. Paterson a,⁎ a Plant Genome Mapping Laboratory, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30605, USA b Center for Genomics and Biocomputing, College of Sciences, Hebei Polytechnic University, Tangshan, Hebei, 063000, China c NRC on DNA Fingerprinting, NBPGR, Pusa Campus, New Delhi, 110012, India article info abstract Article history: Genetic mapping studies have suggested that diploid cotton (Gossypium) might be an ancient polyploid. Received 17 November 2010 However, further evidence is lacking due to the complexity of the genome and the lack of sequence resources. Accepted 15 February 2011 Here, we used the grape (Vitis vinifera) genome as an out-group in two different approaches to further explore Available online 22 February 2011 evidence regarding ancient genome duplication (WGD) event(s) in the diploid Gossypium lineage and its (their) effects: a genome-level alignment analysis and a local-level sequence component analysis. Both Keywords: Gossypium studies suggest that at least one round of genome duplication occurred in the Gossypium lineage. Also, gene Lineage specific genome-wide duplication densities in corresponding regions from Gossypium raimondii, V. vinifera, Arabidopsis thaliana and Carica Vitis vinifera papaya genomes are similar, despite the huge difference in their genome sizes and the different number of Whole genome alignment WGDs each genome has experienced.