The Business of Media Distribution Monetizing Film, TV, and Video Content in an Online World Second Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Internationalbusiness Celebrating 30 Years of Publication!

JOURNAL OF THE UNITED STATES COUNCIL FOR INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS SPRING 2008 VOL. XXX, NO. 1 INTERNATIONALBUSINESS Celebrating 30 Years of Publication! Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting and Piracy page 3 Inside Emerging investment challenges 2 Addressing forced labor 4 A passport for goods 9 Vivendi Chairman Jean-René Fourtou and other BASCAP leadersUSCIB meet International in the UnitedBusiness States Spring 2008for the www.uscib.org first time 1to weigh new weapons in the global fight against fake products the first Peter M. Robinson, President and CEO, USCIB word Policy makers must come to terms with both sovereign wealth and subsidized takeovers. New Financial Challenges on the Horizon Government-controlled investors – including sovereign wealth funds and A new study from the United States Council Foundation, USCIB’s research state-owned enterprises – have gained a sizeable influence in international and educational arm, investigates several recent cases of subsidized finance business and finance. The total value of sovereign wealth worldwide already in cross-border M&A transactions, and suggests corrective measures that amounts to several trillions of dollars, and it is expected to multiply many should be taken to head off the possibility of protectionist overreaction to times over during the coming decade. subsidized investments. The paper, “Investment Subsidies for Cross-Border M&A: Trends and Policy Implications,” is authored by Gary Hufbauer and This raises unique public policy issues: sovereign investors may provoke Thomas Moll of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, and national security concerns, spur fears of market volatility and financial in- Luca Rubini of the Birmingham Law School (UK). -

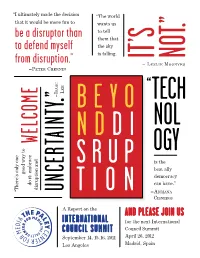

Be a Disruptor Than to Defend Myself from Disruption.”

“I ultimately made the decision “The world that it would be more fun to wants us be a disruptor than to tell them that to defend myself the sky is falling. from disruption.” IT’s NOT.” – Le s L i e Mo o n v e s –Pe t e r Ch e r n i n aac e e s i ” – L “ . BEYO TECH NOL WELCOME NDDI OGY SRUP is the best ally democracy can have.” disruption and UNCERTAINTY good way to do it: embrace “There’s only one TION –Ad r i A n A Ci s n e r o s A Report on the AND PLEASE JOIN US INTERNATIONAL for the next International COUNCIL SUMMIT Council Summit September 14, 15, 16, 2011 April 26, 2012 Los Angeles Madrid, Spain CONTENTS A STEP BEYOND DISRUPTION 3 | A STEP BEYOND DISRUPTION he 2011 gathering of The Paley Center for Me- Tumblr feeds, and other helpful info. In addi- dia’s International Council marked the first time tion, we livestreamed the event on our Web site, 4 | A FORMULA FOR SUCCESS: EMBRacE DISRUPTION in its sixteen-year history that we convened in reaching viewers in over 140 countries. Los Angeles, at our beautiful home in Beverly To view archived streams of the sessions, visit 8 | SNAPSHOTS FROM THE COCKTAIL PaRTY AT THE PaLEY CENTER Hills. There, we assembled a group of the most the IC 2011 video gallery on our Web site at http:// influential thinkers in the global media and en- www.paleycenter.org/ic-2011-la-livestream. -

Dhspring2014 DH Program

Oren Katzeff, Head of Programming, Tastemade Digital Hollywood Spring David Karp, EVP, Business Development, SnagFilms, Inc. The Digital Future has Arrived! Jason Berger, founder & Executive Producer, Kids at Play 1 May 5th - 8th, 2014 Elizabeth Brooks, Head of Marketing, Live Nation Labs The Ritz Carlton Hotel, Marina del Rey, California Sang H. Cho, President and CEO, Mnet Ann Greenberg, Founder & Chief Tinkerer, Sceneplay, The Strategic Sessions - Let's Get Started! Moderator Monday, May 5th Track II: Poolside Tent I (FINANCE) 10:00 AM - 11:15 AM Valuing and Financing Entertainment Content: Track I:Ballroom Terrace (BrandPower) (ADVERT) Movies, Television and Online Video, From VC Native Advertising: Digital Advertising & Equity to Crowdfunding Industry Gets Serious About Better Advertising Join a group of influential players in the media, entertainment Matt Palmer, SVP and GM, Demand Media and tech finance worlds for an enlightening look at emerging Andrew Budkofsky, EVP, Sales and Partnerships, Digital growth areas in our industry. They reveal where the value and Trends opportunities are, who's investing and whether we're headed for Greg Portell, Partner, A.T. Kearney a bubble or sustained hypergrowth in the convergence space. Mike Kisseberth, Chief Revenue Officer, TechMedia Network Mike LaSalle, Partner, Shamrock Capital Advisors Roger Camp, Partner & Chief Creative Officer, CAMP + KING Marti Frucci, Managing Director, Digital Capital Advisors Aron Levitz, SVP, Wattpad René Bourdages, CEO, Elevado Media, Inc. Shawn Gold, Advisor -

2012 Annual Report

2012 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA/ONSTAGE Events ................................................................................................................15 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Special Screenings .................................................................................................................................... 23 Robert M. -

2010 Annual Report

2010 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Media Council Board of Governors ..............................................................................................................12 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA Events .................................................................................................................................14 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Robert M. -

View the Video Overview

tuck cover4:Layout 1 7/16/10 11:16 AM Page 2 fold fold fold turn the page here PARTICIPANTS Steve Abraham Theresa Page Global Leader, Media & Entertainment SVP, Mobile Entertainment IBM Global Business Services GMR Marketing Lars Albright T’05 Robert Quicksilver D’77 VP, Business Development Chief Content Officer Quattro Wireless Tidal TV Jeff Bartlett Rich Ross President and GM President, Disney Channels Worldwide Hearst-Argyle/WMUR-TV Disney-ABC Television Group Tony Bates Jed Simmons T’87 SVP and GM, Service Provider Group Chief Operations Officer Cisco Systems Next New Networks Glenn Britt D’71, T’72 Melody Tan Chairman and CEO SVP, Strategy and Business Operations VIDEO Time Warner Cable for Content Distribution and Marketing Suranga Chandratillake MTV and BET Networks Founder and CEO Blair Westlake blinkx Corporate VP, Media and Entertainment Justin Denison Microsoft SVP Strategy and Market Intelligence Bob Zitter Samsung Telecommunications America EVP, Technology and CTO Keval Desai HBO Director Product Management Google Carrie Ferman T’04 Director Strategic Initiatives NBC Universal Jonathan Hurd This DVD presentation, produced by the Center for Digital Strategies, features Director Altman Vilandrie & Co. CONTRIBUTORS highlights and interviews from the 2008–2009 Britt Technology Impact Series. For additional information and to access our archive of Radio Tuck and Tuck TV Joel Hyatt D’72 Andy Chapman interviews, visit our website: www.tuck.dartmouth.edu/digitalstrategies Co-Founder and CEO Managing Director Current TV MindShare North America Jane Applegate, writer/producer Yvette Kanouff Jennifer E. Childs, program manager Bruce Leichtman Chief Strategy Officer President and Principal Analyst SeaChange International Barbara J. -

Rank1/200) (Rank: 6/200) Rank Company Number Avg

493 Total International Students On Campus Spring 2103 272 Total International COB Students Spring 2013 55% of Total International Student Population 18% of COB Population Computer Systems Analyst Management Analysts (Rank1/200) (Rank: 6/200) Rank Company Number Avg. Salary Rank 1 Infosys Limited 10,154 $73,412 1 2 Cognizant Technology Solutions 1,761 $67,051 2 3 IBM 1,217 $85,232 3 4 Deloitte Consulting 1,111 $79,778 4 5 Satyam Computer Services 1,076 $72,356 5 6 UST Global 1,013 $63,886 6 7 HCL Technologies America 977 $73,009 7 8 Patni Americas 820 $70,699 8 9 Wipro 785 $82,443 9 10 Hexaware Technologies 610 $63,204 10 11 Deloitte Touche 549 $81,179 11 12 Accenture 491 $79,527 12 13 Tata Consultancy Services 381 $65,010 13 14 Mphasis 367 $66,044 14 15 Synechron 358 $77,189 15 16 Capgemini Financial Services 318 $78,030 16 17 Virgo 291 $60,227 17 18 Hewlett Packard 272 $96,771 18 19 Diaspark 270 $64,728 19 20 Yash Technologies 269 $55,205 20 21 Advent Global Solutions 247 $62,220 21 22 RS Software India 243 $67,253 22 23 Infosys Limited 241 $78,296 23 24 Persistent Systems 240 $71,556 24 25 Reliable Software Resources 232 $60,521 25 26 Larsen Toubro Infotech 231 $65,177 26 27 kforce 225 $90,304 27 28 Ernst Young 217 $89,948 28 29 Pricewaterhousecoopers 208 $66,478 29 30 Compunnel Software Group 206 $76,062 30 31 Polaris Software Lab 204 $69,457 31 32 Tech Mahindra americas 204 $64,965 32 33 Horizon Technologies 199 $61,330 33 34 SAP America 198 $102,811 34 35 Orian Engineersorporated 197 $62,835 35 36 Oracle 195 $93,968 36 37 Syntel -

2000 Spring Television Quarterly

JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS AND SCIENCES LINCOLN CITY LIBRARIES "III III II III 1 III 3 3045 01854 1744 hub llerbee e Newswoman Who Fired e- Networks BY ARTHUR UNGER Public Television nd the Camel's Nose Y BERNARD S. REDMONT V's Distorted and 'ssing Images f Women and e Elderly Y BERT R. BRILLER EVISION BULK RATE Ii lkih.hiid1II1 111 I.III, I,II. III II 1II.I,II U.S. POSTAGE RTERLY xxAUTO.xxx.xxxxxxxxxMIXEO HOC 430 CITY' PAID W. 57TH ST. LINCOLN LIBRARIES REFRENCE DEPT. COLUMBUS, OH YO3K 136 S 14TH ST LINCOLN NE 68508 -1801 PERMIT NO. 2443 . 10019 www.americanradiohistory.com Hubbard Broadcasting'.0 bbarc Proudly d casti nc The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences P -FM KS KSTP -AM KSTP- V USSB CONUS F&F Productions Inc. Diamond P Sports All News Channel WD1O -TV WIRT -TV KSAX -TV KRWF -TV KOB-TV KOBR-TV KOBFTV WNYT TV WNEC -TV www.americanradiohistory.com Muchas gracias, muchas gracias. As the first Spanish -language television network to be honored with two national Emmy Awards, we thought some words of thanks were in order. "Gracias" to our talented Noticiero Univision team of anchors, reporters, and producers for their award -winning coverage of last summer's devastating Hurricane Mitch. " Gracias" to the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences for recognizing not just the increasing importance, but the worldclass quality of Spanish- language newscasting in this country. www.americanradiohistory.com e aétte°ate o new ColorStream Pro DVD with Progressive Scan & eue/7,4n ckieectle, Jowni dedyne4e, echto4e, CMdiStAWitt eChjA94e, ca4ne4eaman, aJst'sttan,tt , vi G(.SKIT,G1tct4W, W ¡ re0/ ud10, u1agta eve/7me Jee defix ukO4 de Way aif,W. -

YOU Gave Generously: Corporations Every Year, United Way of King County Recognizes Outstanding Workplace Campaigns with the Spirit of Caring Awards

START IT S W I TH 2009-2010 SPIRIT OF CARING AwaRDS Costco Wholesale takes top honors at United Way’s Spirit of Caring Celebration YOU gave generously: Corporations Every year, United Way of King County recognizes outstanding workplace campaigns with the Spirit of Caring Awards. Costco Wholesale received the 2009-2010 Spirit of Puget Sound Award, King County’s highest achievement in corporate philanthropy. It honors outstanding community involvement, sustained campaign excellence and the promotion of volunteerism. For the 2009-2010 campaign season, the employees of Costco Wholesale showed incredible heart and boundless generosity. Chairman Jeff Brotman’s and CEO Jim Sinegal’s strong leadership and commitment to United Way of King County resonated throughout the company, and made this campaign year an exceptional success. Leadership Giving (gifts of $1,000 and above) jumped 7 percent company-wide, and overall participation was 84 percent—a 33 percent increase. Adding to Costco’s campaign success was its innovative new Express Pledge System. This point-of-sale pledge system for employees enabled gifts to go directly to United Way of King County in $5 increments, which generated nearly $60,000. Lauren Kutschka accepted the award on Costco’s behalf In all, Costco’s Northwest region raised $3.7 million for United Way of King County during a superb campaign. Costco employees also gave generously of their time, volunteering on Day of Caring. Executive of the Year Award Most Significant Increase Award Recognizing an exceptional level of support for United Way For exceptional campaign growth of King County by a top executive Charter Bank Sandy Gregory, Seattle Seahawks TOP 40 SUPPORTERS OF UNITED way OF KING COUNTY First Place School Companies listed gave between July 1, 2009 and June 30, 2010 Ambassador of the Year INCA Engineers Inc. -

Product Guideguide

MIPT V PRODUCTPRODUCT GUIDEGUIDE LOVE CRUISE 2001CHRIS COLORADO 2 222 FBC A AAA Animation (6x26’) Reality Series (7 x 60min.) Language: French (original version), Cast: Sixteen Eligible Singles Dubbed English, 20TH CENTURY FOX Exec. Prods. Jonathan Murray, Mary- A&E Director: Franck Bertrand, Thibaut INTERNATIONAL Ellis Bunim Arts & Entertainment, A&E Television Chatel, Jacqueline Monsigny Audiences will cruise through the south- Network / The History Channel, 235 East Produced by: AB Productions and TELEVISION ern Caribbean and visit exotic enezuelan 45th Street, New York, NY 10017 USA. Studios Animage 20th Century Fox International ports with eighteen eligible single men Tel: 212.210.1400. Fax: 212.983.4370. Co-producers: MEDIASET /CANAL + / Television, P.O. Box 900, Beverly Hills, and women who are in competition to find At MIP-TV: Carl Meyer (Regional France 3 / AB PRODUCTIONS CA 90213-0900. Tel 310.369.1000. love and to gain an extraordinary grand Managing Director, Asia), Chris O’Keefe Delivery Status: Completed Australia Office: 20th Century Fox prize. (Regional Managing Director, Latin Budget: 43 MF International TV, Level 5, Frank Hurley KATE BRASHER America), Shelley Blaine Goodman (VP, Danger lurks, group of 666’ agents, have Grandstand, Fox Studios Australia. CBS Affiliates Sales, Canada), Maria infiltrated the higher levels power of the Driver Avenue, Moore Park NSW 1363, Drama (6 x 30 min.) Komodikis (SVP, International Managing world federation. Chris Colorado becomes Australia. Tel 61.2.8353.2200. Fax Cast: Mary Stuart Masterson, Rhea Director) the President’s man to save democracy and 61.2.8353.2205. Brazil Office: Fox Film Perlman, and Hector Elizondo Office: E3-08 peace. -

Vendors Payments

Vendors Payments The image The image cannot be cannot be displayed. Your displayed. Your computer may computer may not have not have enough enough memory to Regular Vendors memory to Regular Vendors $ 275,228,292.64 1ST RESPONSE TOWING INC 167223 $ 345.00 22ND CENTURY STAFFING INC 166767 $ 9,002.50 3 B'S INC 130384 $ 1,767.50 333 6TH STREET LLC 165858 $ 57,827.10 3D VISIONS INC 163619 $ 1,050.00 3M COMPANY 102220 $ 40,452.83 4 THE TRUCK 166313 $ 9,184.94 4IMPRINT INC 105038 $ 551.81 4LEAF CONSULTING LLC 160792 $ 716,994.61 70 LIMITED PARTNERSHIP 168682 $ 38,000,000.00 818 FLAMINGO COMPANY 167309 $ 2,319.00 84 LUMBER COMPANY 131949 $ 1,973.87 A & A UNIFORMS INC 102856 $ 2,615.97 A & B ENVIRONMENTAL LLC 120671 $ 15,420.00 A & B SECURITY GROUP INC 103501 $ 4,501.00 A & D AUTOMATIC GATE AND 100035 $ 820.00 A & G TOWING 123562 $ 80.00 A & R REID ENTERPRISES INC 166140 $ 395.10 A ABLE MINI STORAGE 122134 $ 405.00 A ADAMS &/OR US TREASURY 159194 $ 1,750.00 A BACA &/OR WYOMING C S 132102 $ 3,553.83 A BETTER LIFE 124683 $ 3,680.00 A COMPANY INC 102887 $ 525. 00 A D L HOME CARE INC 103985 $ 31,200.00 A DAVIS & OR STATE DISBURSEMENT 140448 $ 645.12 A DODGE &/OR LV CONSTABLE 167113 $ 1,988.91 A GARBUTT &/OR US TREASURY 162481 $ 700.00 A HELPING HAND HOME HEALTH CARE 106117 $ 46,803.75 INC A HONEY WAGON INC 138408 $ 27,657.50 A K EDGERLY &/OR US TREASURY 168120 $ 919.08 A KELLY &/OR NLV CONSTABLE 168114 $ 529.02 A KING &/OR MISDU 154359 $ 819.07 A MEDINA &/OR GREAT LAKES HIGHER 168230 $ 188.46 A NLV CAB CO 100177 $ 1,269.20 A PEARSON &/OR INSCCU 162945 -

194969015.Pdf

Anyone who wants to know more about how films and TV shows are dis- tributed and exploited can learn a huge amount from this book. —Jim Morris, Pixar Animation Studios General Manager, EVP, Production, and Producer Wall•E The entertainment industry is an industry with ongoing challenges with constant change. Jeff provides a road map to see where you are going by understanding where you started. —Louis Feola, President, Paramount Famous Productions Ulin expertly depicts the fluid nature of content creation and distribution in a concise and understandable way. There’s never been a better insider’s look at the choices and challenges that studio executives face every day. —Gary Marenzi, President, MGM Worldwide Television Jeff Ulin’s broad spectrum of expertise, spanning all aspects of motion pic- ture and television distribution, from theatrical to home entertainment to new media and television licensing, render him uniquely qualified to illu- minate the business side of the entertainment business. —Hal Richardson, President of Paramount Worldwide Television Jeff Ulin’s book is a must read for practitioners, academics and potential in- vestors in the new media space. Having worked in all segments of the indus- try, Ulin brings together a unique combination of experience and analytical rigor to deconstruct the driving forces of an industry in dynamic change. —Pablo Spiller, Jeffrey A. Jacobs Distinguished Professor of Business and Technology, Haas School of Business. This is the book that everyone in the business has been waiting for — Jeff’s seen it all, and has written a must-read book for those wanting to under- stand the jigsaw of media distribution and in what ways the web is influ- encing how, when and where money is made.