Contouring Urban Citizenship in Postcolonial Chennai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polio Vaccination Centers for International Travelers Travelling to Seven Polio Endemic Country Tamil Nadu Telephone Number of Name and Adress of Designated S

Polio Vaccination Centers for International Travelers travelling to Seven Polio endemic country_Tamil Nadu Telephone Number of Name and Adress of Designated S. No. Name of District/Urban Designated OPV Vaccination Name of Designated Official OPV Vaccination Center Center The Deputy Director of Health Services No. 2/457, 1 ARIYALUR Jayangondam Main Road, DDHS-9443013200 Dr. A. Mohan (Opp to District Collector©s Office) Valajanagaram, Ariyalur -621704. The Deputy Director of Health Services 107-A Race Course Office-0422-2220351 2 COIMBATORE Dr. S. Somasundaram Road, DDHS-9943030055 Coimbatore ± 641 018. The Deputy Director of Health Office -04142-295134 3 CUDDALORE Services, Beach Road, Dr. K.R. Jawaharlal DDHS-9442534652 Cuddalore ± 607 001. The Deputy Director of Health Services Collectorate Campus, Office- 04342-232720 DDHS- 4 DHARMAPURI Dr. V. Vijayalakshmi Dharmapuri - 636 9841673515 705. The Deputy Director of Health office : 0451-2432817 & 0451- Services 1/127 A, Meenakshi 5 DINDIGUL 2441232 Dr. S. Soundammal Naikken Patti (Po) DDHS 9962560901 Dindigul ± 624 002. The Deputy Director of Health Services Government Head Quarters, office : 0424-2258020 6 ERODE Dr. P. Balusamy Hospital Campus, DDHS-9443715335 Erode ± 638 009. The Deputy Director of Health Services , 42 A , Railway Road, office :27222019 7 KANCHEEPURAM Dr. K. Krishnaraj Arignar Anna Memorial DDHS-9443547147 Cancer Institute Campus, Kanchipuram ± 631 501. The Deputy Director of Health Services, District Offices Campus Office :04324-255340 8 KARUR 2nd floor, Collectorate Campus, Dr. V. Nalini DDHS-9442552692 Thanthonimalai, Karur ± 639 007. The Deputy Director of Health Services Behind Collectorate, Office :04343-232830 9 KRISHNAGIRI Via RTO Dr. B. Premkumar DDHS-9842252154 office, Krishnagiri - 635 001. -

Thiruvallur District

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR 2017 TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT tmt.E.sundaravalli, I.A.S., DISTRICT COLLECTOR TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT TAMIL NADU 2 COLLECTORATE, TIRUVALLUR 3 tiruvallur district 4 DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT - 2017 INDEX Sl. DETAILS No PAGE NO. 1 List of abbreviations present in the plan 5-6 2 Introduction 7-13 3 District Profile 14-21 4 Disaster Management Goals (2017-2030) 22-28 Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability analysis with sample maps & link to 5 29-68 all vulnerable maps 6 Institutional Machanism 69-74 7 Preparedness 75-78 Prevention & Mitigation Plan (2015-2030) 8 (What Major & Minor Disaster will be addressed through mitigation 79-108 measures) Response Plan - Including Incident Response System (Covering 9 109-112 Rescue, Evacuation and Relief) 10 Recovery and Reconstruction Plan 113-124 11 Mainstreaming of Disaster Management in Developmental Plans 125-147 12 Community & other Stakeholder participation 148-156 Linkages / Co-oridnation with other agencies for Disaster 13 157-165 Management 14 Budget and Other Financial allocation - Outlays of major schemes 166-169 15 Monitoring and Evaluation 170-198 Risk Communications Strategies (Telecommunication /VHF/ Media 16 199 / CDRRP etc.,) Important contact Numbers and provision for link to detailed 17 200-267 information 18 Dos and Don’ts during all possible Hazards including Heat Wave 268-278 19 Important G.Os 279-320 20 Linkages with IDRN 321 21 Specific issues on various Vulnerable Groups have been addressed 322-324 22 Mock Drill Schedules 325-336 -

Telephone Numbers

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY THANJAVUR IMPORTANT TELEPHONE NUMBERS DISTRICT EMERGENCY OPERATION CENTRE THANJAVUR DISTRICT YEAR-2018 2 INDEX S. No. Department Page No. 1 State Disaster Management Department, Chennai 1 2. Emergency Toll free Telephone Numbers 1 3. Indian Meteorological Research Centre 2 4. National Disaster Rescue Team, Arakonam 2 5. Aavin 2 6. Telephone Operator, District Collectorate 2 7. Office,ThanjavurRevenue Department 3 8. PWD ( Buildings and Maintenance) 5 9. Cooperative Department 5 10. Treasury Department 7 11. Police Department 10 12. Fire & Rescue Department 13 13. District Rural Development 14 14. Panchayat 17 15. Town Panchayat 18 16. Public Works Department 19 17. Highways Department 25 18. Agriculture Department 26 19. Animal Husbandry Department 28 20. Tamilnadu Civil Supplies Corporation 29 21. Education Department 29 22. Health and Medical Department 31 23. TNSTC 33 24. TNEB 34 25. Fisheries 35 26. Forest Department 38 27. TWAD 38 28. Horticulture 39 29. Statisticts 40 30. NGO’s 40 31. First Responders for Vulnerable Areas 44 1 Telephone Number Officer’s Details Office Telephone & Mobile District Disaster Management Agency - Thanjavur Flood Control Room 1077 04362- 230121 State Disaster Management Agency – Chennai - 5 Additional Cheif Secretary & Commissioner 044-28523299 9445000444 of Revenue Administration, Chennai -5 044-28414513, Disaster Management, Chennai 044-1070 Control Room 044-28414512 Emergency Toll Free Numbers Disaster Rescue, 1077 District Collector Office, Thanjavur Child Line 1098 Police 100 Fire & Rescue Department 101 Medical Helpline 104 Ambulance 108 Women’s Helpline 1091 National Highways Emergency Help 1033 Old Age People Helpline 1253 Coastal Security 1718 Blood Bank 1910 Eye Donation 1919 Railway Helpline 1512 AIDS Helpline 1097 2 Meteorological Research Centre S. -

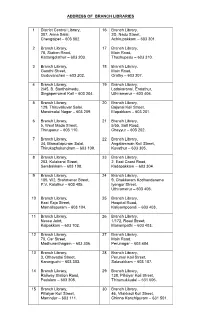

Branch Libraries List

ADDRESS OF BRANCH LIBRARIES 1 District Central Library, 16 Branch Library, 307, Anna Salai, 2D, Nadu Street, Chengalpet – 603 002. Achirupakkam – 603 301. 2 Branch Library, 17 Branch Library, 78, Station Road, Main Road, Kattangolathur – 603 203. Thozhupedu – 603 310. 3 Branch Library, 18 Branch Library, Gandhi Street, Main Road, Guduvancheri – 603 202. Orathy – 603 307. 4 Branch Library, 19 Branch Library, 2/45, B. Santhaimedu, Ladakaranai, Endathur, Singaperrumal Koil – 603 204. Uthiramerur – 603 406. 5 Branch Library, 20 Branch Library, 129, Thiruvalluvar Salai, Bajanai Koil Street, Maraimalai Nagar – 603 209. Elapakkam – 603 201. 6 Branch Library, 21 Branch Library, 5, West Mada Street, 5/55, Salt Road, Thiruporur – 603 110. Cheyyur – 603 202. 7 Branch Library, 22 Branch Library, 34, Mamallapuram Salai, Angalamman Koil Street, Thirukazhukundram – 603 109. Kuvathur – 603 305. 8 Branch Library, 23 Branch Library, 203, Kulakarai Street, 2, East Coast Road, Sembakkam – 603 108. Kadapakkam – 603 304. 9 Branch Library, 24 Branch Library, 105, W2, Brahmanar Street, 9, Chakkaram Kodhandarama P.V. Kalathur – 603 405. Iyengar Street, Uthiramerur – 603 406. 10 Branch Library, 25 Branch Library, East Raja Street, Hospital Road, Mamallapuram – 603 104. Kaliyampoondi – 603 403. 11 Branch Library, 26 Branch Library, Nesco Joint, 1/172, Road Street, Kalpakkam – 603 102. Manampathi – 603 403. 12 Branch Library, 27 Branch Library, 70, Car Street, Main Road, Madhuranthagam – 603 306. Perunagar – 603 404. 13 Branch Library, 28 Branch Library, 3, Othavadai Street, Perumal Koil Street, Karunguzhi – 603 303. Salavakkam – 603 107. 14 Branch Library, 29 Branch Library, Railway Station Road, 138, Pillaiyar Koil Street, Padalam – 603 308. -

Indusrialization of the Madurai-Tuticorin Corridor

INDUSTRIALIZATION OF THE MADURAI – TUTICORIN CORRIDOR THE UNEXPLORED OPPORTUNITY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY For Confederation of Indian Industry By Scope e-Knowledge Center Pvt Ltd Table of Contents SI.NO Topic Page No 1 Introduction 3 i. Introduction 4 ii. Methodology and Approach 4 iii. Framework of Analysis 5 2 Key Indicators 6 i. Demographics and Key Economic 7 Indicators, 2003 ii. Infrastructure 7 ii. Existing Resources, Industries & 11 Clusters 3 Way Forward – The Hubs, The 12 Satellites And The Corridors i. The Approach for the Industrial 13 Development of the Corridor ii. Roles to be played 18 iii. Conclusions & Outlook 20 1.0 Introduction Introduction The Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), Tamil Nadu branch’s Task Force for Industrialisation of Tamil Nadu, has appointed Scope e-Knowledge Center Pvt. Ltd., Chennai to carry out a study on the industrialisation potential of the southern districts of Tamil Nadu and suggest the way forward for achieving the objective. This report covers seven districts: Madurai, Virudhunagar, Ramanathapuram, Tirunelveli, Sivagangai, Tuticorin and Kanniyakumari. It is based on extensive discussions with government officials, industries, trade, services, CII council members and NGOs, in every district covered as well as exhaustive secondary and Internet research. The study was conducted by Scope e-Knowledge Center, Chennai, in partnership with Madras Consultancy Group, Chennai. Methodology and Approach • The study employed a combination of Primary & Secondary research tools • Secondary Research helped in -

RK Nagar Suffers Despite Promises

Volume No 17 Issue No 10 April 3, 2017 LAB JOURNAL OF THE ASIAN COLLEGE OF JOURNALISM Decriminalising EMA bans drugs Football inspires Suicide tested in India children Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 A\ SMITABHA MANNA yet to be taken to maintain solid radius of the Government Jayalalithaa's pending initiatives Rs 360 crore started by Amma,'' RK Nwaste magnagemenat,'' sayrs T. suffers desPeriphperal iHotspitale in foprward. Orne briodge and am flyover siays sKannane, a shops owner in Unkept promises and neglect of Naveenkumar, a resident of Tondiarpet.'' project connecting Coronation Tondiarpet. severe health issues plague the RK Korukkupet and an advocate with Korukkupet residents are also Nagar to Ezhil Nagar worth Rs 117 Kannan like many others is a Nagar constituency where some 60 the High Court. receiving similar muddy and crore is in limbo after her demise. worried resident because there is candidates are in the fray for the The residents are left gasping for brackish water for drinking and The project is crucial as in the no water sometimes for weeks and April 12 by-election. breath when smoke from burning household purposes since January absence of an over-bridge or a there is improper management of The Kodungaiyur dumpyard, a garbage and medical waste fills the and are plagued by cholera as subway the road near Korukkupet Amma Unvagams. He adds that 110-acre garbage disposal area is area. A canal to divert the sewage well as malaria infections. railway station gets congested and Amma canteens have stopped an environmental concern for the and waste from the dump yard that Primary health care is not traffic is stalled for hours. -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction The Invention of an Ethnic Nationalism he Hindu nationalist movement started to monopolize the front pages of Indian newspapers in the 1990s when the political T party that represented it in the political arena, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP—which translates roughly as Indian People’s Party), rose to power. From 2 seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian parliament, the BJP increased its tally to 88 in 1989, 120 in 1991, 161 in 1996—at which time it became the largest party in that assembly—and to 178 in 1998. At that point it was in a position to form a coalition government, an achievement it repeated after the 1999 mid-term elections. For the first time in Indian history, Hindu nationalism had managed to take over power. The BJP and its allies remained in office for five full years, until 2004. The general public discovered Hindu nationalism in operation over these years. But it had of course already been active in Indian politics and society for decades; in fact, this ism is one of the oldest ideological streams in India. It took concrete shape in the 1920s and even harks back to more nascent shapes in the nineteenth century. As a movement, too, Hindu nationalism is heir to a long tradition. Its main incarnation today, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS—or the National Volunteer Corps), was founded in 1925, soon after the first Indian communist party, and before the first Indian socialist party. -

The Chennai Comprehensive Transportation Study (CCTS)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The consultants are grateful to Tmt. Susan Mathew, I.A.S., Addl. Chief Secretary to Govt. & Vice-Chairperson, CMDA and Thiru Dayanand Kataria, I.A.S., Member - Secretary, CMDA for the valuable support and encouragement extended to the Study. Our thanks are also due to the former Vice-Chairman, Thiru T.R. Srinivasan, I.A.S., (Retd.) and former Member-Secretary Thiru Md. Nasimuddin, I.A.S. for having given an opportunity to undertake the Chennai Comprehensive Transportation Study. The consultants also thank Thiru.Vikram Kapur, I.A.S. for the guidance and encouragement given in taking the Study forward. We place our record of sincere gratitude to the Project Management Unit of TNUDP-III in CMDA, comprising Thiru K. Kumar, Chief Planner, Thiru M. Sivashanmugam, Senior Planner, & Tmt. R. Meena, Assistant Planner for their unstinted and valuable contribution throughout the assignment. We thank Thiru C. Palanivelu, Member-Chief Planner for the guidance and support extended. The comments and suggestions of the World Bank on the stage reports are duly acknowledged. The consultants are thankful to the Steering Committee comprising the Secretaries to Govt., and Heads of Departments concerned with urban transport, chaired by Vice- Chairperson, CMDA and the Technical Committee chaired by the Chief Planner, CMDA and represented by Department of Highways, Southern Railways, Metropolitan Transport Corporation, Chennai Municipal Corporation, Chennai Port Trust, Chennai Traffic Police, Chennai Sub-urban Police, Commissionerate of Municipal Administration, IIT-Madras and the representatives of NGOs. The consultants place on record the support and cooperation extended by the officers and staff of CMDA and various project implementing organizations and the residents of Chennai, without whom the study would not have been successful. -

India Freedom Fighters' Organisation

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of Political Pamphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Part 5: Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of POLITICAL PAMPHLETS FROM THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT PART 5: POLITICAL PARTIES, SPECIAL INTEREST GROUPS, AND INDIAN INTERNAL POLITICS Editorial Adviser Granville Austin Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Indian political pamphlets [microform] microfiche Accompanied by printed guide. Includes bibliographical references. Content: pt. 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups—pt. 2. Indian Internal Politics—[etc.]—pt. 5. Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics ISBN 1-55655-829-5 (microfiche) 1. Political parties—India. I. UPA Academic Editions (Firm) JQ298.A1 I527 2000 <MicRR> 324.254—dc20 89-70560 CIP Copyright © 2000 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-829-5. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................. vii Source Note ............................................................................................................................. xi Reference Bibliography Series 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups Organization Accession # -

18R Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

18R bus time schedule & line map 18R Broadway - Nanganallur View In Website Mode The 18R bus line (Broadway - Nanganallur) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Broadway: 5:45 AM - 7:45 PM (2) Cement Road: 1:00 PM - 10:25 PM (3) Cement Road: 1:40 PM (4) Nanganallur: 6:25 AM - 9:05 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 18R bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 18R bus arriving. Direction: Broadway 18R bus Time Schedule 32 stops Broadway Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:45 AM - 7:45 PM Monday 5:45 AM - 7:45 PM Nanganallur Tuesday 5:45 AM - 7:45 PM Nanganallur Mgr Road MGR Road, Chennai Wednesday 5:45 AM - 7:45 PM Vetri Vel Thursday 5:45 AM - 7:45 PM Friday 5:45 AM - 7:45 PM Roja Medicals Bus Stop Saturday 5:45 AM - 7:45 PM Chidambaram Stores Market Road Bus Stop Pazavanthangal Road Junction 18R bus Info Direction: Broadway Junction Of Palavanthangal & GST Stops: 32 Trip Duration: 44 min Alandur Cement Road Line Summary: Nanganallur, Nanganallur Mgr Road, Vetri Vel, Roja Medicals Bus Stop, Chidambaram Stores, Market Road Bus Stop, Pazavanthangal Alandur Depot Road Junction, Junction Of Palavanthangal & GST, Alandur Cement Road, Alandur Depot, Ota Metro Ota Metro Station Station, Cantonment Board (St. Thomas Mount Head Post O∆ce), Prnaipalai / Alandur, Guindy R.S, Cantonment Board (St. Thomas Mount Head Chellammal College, Panagal Maligai, Saidapet, Raja Post O∆ce) Hostel, S.H.B., Nandanam Military Quarters, Vanavali, D.M.S.Metro Station, Gemini, Anand Prnaipalai / Alandur Theatre, Spensor Plaza (Tvs), LIC, Mount Road Post O∆ce, Shanthi Theatre, Simpsons / Periyar Bridge, Guindy R.S Pallavan Salai/Periyar Bridge, Central R.S. -

Stabilization of Sludge from AAVIN Dairy Processing Plant (Chennai) Using Vermicomposting

Available online www.jocpr.com Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research, 2015, 7(3):846-851 ISSN : 0975-7384 Research Article CODEN(USA) : JCPRC5 Stabilization of sludge from AAVIN dairy processing plant (Chennai) using Vermicomposting Anusha S.* and Pratheeba Paul Department of Civil Engineering, Hindustan Institute of Technology & Science, Hindustan University, Padur, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Land pollution has become a serious problem in the present scenario and resolving this issue is yet another challenging task. Solid wastes contribute to serious threats on environmental hazards and it has become the need of the hour to develop sustainable methods in handling them by enhancing cleaner technologies in recycling and thereby creating safe environment adding organic fertility to soil. Dairy industry is an important sector in both the developed and developing nations and the pollutants from these consists of organic compounds with enormous amounts of suspended solids, biochemical oxygen demand and chemical oxygen demand along with nitrate compounds. The wastewater from dairy industries when dumped or land filled has various disadvantages of being expensive occupying more open space resulting in polluting the ground water and soil resources. In the present work, the dairy sludge from AAVIN industry, Chennai was stabilized by the technique of vermiconversion. Initially dairy sludge and cow dung of varying proportions of 1:2 and 2:2 were mixed and earthworms of two different species called Eisenia foetida and Eudrilus Eugenia were added to the contents for about 55 days to create vermicomposting. The vermicomposted sludge exhibited very good results in comparison to normal sludge and were added to the radish plants where they yielded good growth results. -

Bus Routes & Timings

BUS ROUTES & TIMINGS ACADEMIC YEAR 2015 - 2016 ROUTE NO. 15 ROUTE NO. 1 to 12, 50, 54, 55, 56, 61,64,88, RAJA KILPAKKAM TO COLLEGE 113,117 to 142 R2 - RAJ KILPAKKAM : 07.35 a.m. TAMBARAM TO COLLEGE M11 - MAHALAKSHMI NAGAR : 07.38 a.m. T3 - TAMBARAM : 08.20 a.m. C2 - CAMP ROAD : 07.42 a.m. COLLEGE : 08.40 a.m. S11 - SELAIYUR : 07.44 a.m. A4 - ADHI NAGAR : 07.47 a.m. ROUTE NO. 13 C19 - CONVENT SCHOOL : 07.49 a.m. KRISHNA NAGAR - ITO COLLEGE COLLEGE : 08.40 a.m. K37 - KRISHNA NAGAR (MUDICHUR) : 08.00 a.m. R4 - RAJAAMBAL K.M. : 08.02 a.m. ROUTE NO. 16 NGO COLONY TO COLLEGE L2 - LAKSHMIPURAM SERVICE ROAD : 08.08 a.m. N1 - NGO COLONY : 07.45 a.m. COLLEGE : 08.40 a.m. K6 - KAKKAN BRIDGE : 07.48 a.m. A3 - ADAMBAKKAM : 07.50 a.m. (POLICE STATION) B12 – ROUTE NO. 14 BIKES : 07.55 a.m. KONE KRISHNA TO COLLEGE T2 - T. G. NAGAR SUBWAY : 07. 58 a.m. K28 - KONE KRISHNA : 08.05 a.m. T3 - TAMBARAM : 08.20 a.m. L5 - LOVELY CORNER : 08.07 a.m. COLLEGE : 08.40 a.m. ROUTE NO. 17 ADAMBAKKAM - II TO COLLEGE G3 - GANESH TEMPLE : 07.35 a.m. V13 - VANUVAMPET CHURCH : 07.40 a.m. J3 - JAYALAKSHMI THEATER : 07.43 a.m. T2 - T. G. NAGAR SUBWAY : 07.45 a.m. T3 - TAMBARAM : 08.20 a.m. COLLEGE : 08.40 a.m. ROUTE NO. 18 KANTHANCHAVADI TO COLLEGE ROUTE NO.19 NANGANALLUR TO COLLEGE T 43 – THARAMANI Rly.