The Patrolling War in Tobruk Abstract Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military History Anniversaries 01 Thru 14 Feb

Military History Anniversaries 01 thru 14 Feb Events in History over the next 14 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Feb 01 1781 – American Revolutionary War: Davidson College Namesake Killed at Cowan’s Ford » American Brigadier General William Lee Davidson dies in combat attempting to prevent General Charles Cornwallis’ army from crossing the Catawba River in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. Davidson’s North Carolina militia, numbering between 600 and 800 men, set up camp on the far side of the river, hoping to thwart or at least slow Cornwallis’ crossing. The Patriots stayed back from the banks of the river in order to prevent Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tartleton’s forces from fording the river at a different point and surprising the Patriots with a rear attack. At 1 a.m., Cornwallis began to move his troops toward the ford; by daybreak, they were crossing in a double-pronged formation–one prong for horses, the other for wagons. The noise of the rough crossing, during which the horses were forced to plunge in over their heads in the storm-swollen stream, woke the sleeping Patriot guard. The Patriots fired upon the Britons as they crossed and received heavy fire in return. Almost immediately upon his arrival at the river bank, General Davidson took a rifle ball to the heart and fell from his horse; his soaked corpse was found late that evening. Although Cornwallis’ troops took heavy casualties, the combat did little to slow their progress north toward Virginia. -

Medical Conditions in the Western Desert and Tobruk

CHAPTER 1 1 MEDICAL CONDITIONS IN THE WESTERN DESERT AND TOBRU K ON S I D E R A T I O N of the medical and surgical conditions encountered C by Australian forces in the campaign of 1940-1941 in the Wester n Desert and during the siege of Tobruk embraces the various diseases me t and the nature of surgical work performed . In addition it must includ e some assessment of the general health of the men, which does not mean merely the absence of demonstrable disease . Matters relating to organisa- tion are more appropriately dealt with in a later chapter in which the lessons of the experiences in the Middle East are examined . As told in Chapter 7, the forward surgical work was done in a main dressing statio n during the battles of Bardia and Tobruk . It is admitted that a serious difficulty of this arrangement was that men had to be held for some tim e in the M.D.S., which put a brake on the movements of the field ambulance , especially as only the most severely wounded men were operated on i n the M.D.S. as a rule, the others being sent to a casualty clearing statio n at least 150 miles away . Dispersal of the tents multiplied the work of the staff considerably. SURGICAL CONDITIONS IN THE DESER T Though battle casualties were not numerous, the value of being able to deal with varied types of wounds was apparent . In the Bardia and Tobruk actions abdominal wounds were few. Major J. -

Brevity, Skorpion & Battleaxe

DESERT WAR PART THREE: BREVITY, SKORPION & BATTLEAXE OPERATION BREVITY MAY 15 – 16 1941 Operation Sonnenblume had seen Rommel rapidly drive the distracted and over-stretched British and Commonwealth forces in Cyrenaica back across the Egyptian border. Although the battlefront now lay in the border area, the port city of Tobruk - 100 miles inside Libya - had resisted the Axis advance, and its substantial Australian and British garrison of around 27,000 troops constituted a significant threat to Rommel's lengthy supply chain. He therefore committed his main strength to besieging the city, leaving the front line only thinly held. Conceived by the Commander-in-Chief of the British Middle East Command, General Archibald Wavell, Operation Brevity was a limited Allied offensive conducted in mid-May 1941. Brevity was intended to be a rapid blow against weak Axis front-line forces in the Sollum - Capuzzo - Bardia area of the border between Egypt and Libya. Operation Brevity's main objectives were to gain territory from which to launch a further planned offensive toward the besieged Tobruk, and the depletion of German and Italian forces in the region. With limited battle-ready units to draw on in the wake of Rommel's recent successes, on May 15 Brigadier William Gott, with the 22nd Guards Brigade and elements of the 7th Armoured Division attacked in three columns. The Royal Air Force allocated all available fighters and a small force of bombers to the operation. The strategically important Halfaya Pass was taken against stiff Italian opposition. Reaching the top of the Halfaya Pass, the 22nd Guards Brigade came under heavy fire from an Italian Bersaglieri (Marksmen) infantry company, supported by anti-tank guns, under the command of Colonel Ugo Montemurro. -

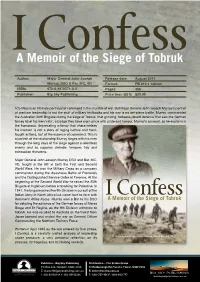

A Memoir of the Siege of Tobruk

I Confess A Memoir of the Siege of Tobruk Author: Major General John Joseph Release date: August 2011 Murray, DSO & Bar, MC, VD Format: PB 210 x 148mm ISBN: 978-0-9870574-8-8 Pages: 256 Publisher: Big Sky Publishing Price (incl. GST): $29.99 I Confess is an intimate portrayal of command in the crucible of war. But Major General John Joseph Murray’s portrait of wartime leadership is not the stuff of military textbooks and his war is no set-piece battle. Murray commanded the Australian 20th Brigade during the siege of Tobruk, that grinding, tortuous desert defence that saw the German forces label his men ‘rats’, a badge they have worn since with pride and honour. Murray’s account, as he explains in the humorous, deprecating whimsy that characterises his memoir, is not a story of raging battles and hard- fought actions, but of the essence of command. This is a portrait of the relationship Murray forges with his men through the long days of the siege against a relentless enemy and as supplies dwindle, tempers fray and exhaustion threatens. Major General John Joseph Murray DSO and Bar, MC, VD, fought in the AIF in both the First and Second World Wars. He won the Military Cross as a company commander during the disastrous Battle of Fromelles and the Distinguished Service Order at Peronne. At the beginning of the Second World War he raised the 20th Brigade at Ingleburn before embarking for Palestine. In 1941, the brigade joined the 9th Division in pursuit of the Italian Army in North Africa but came face to face with Rommel’s Afrika Korps. -

(June 1941) and the Development of the British Tactical Air Doctrine

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 14, ISSUE 1, FALL 2011 Studies A Stepping Stone to Success: Operation Battleaxe (June 1941) and the Development of the British Tactical Air Doctrine Mike Bechthold On 16 February 1943 a meeting was held in Tripoli attended by senior American and British officers to discuss the various lessons learned during the Libyan campaign. The focus of the meeting was a presentation by General Bernard Montgomery. This "gospel according to Montgomery," as it was referred to by Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder, set out very clearly Monty's beliefs on how air power should be used to support the army.1 Among the tenets Montgomery articulated was his conviction of the importance of air power: "Any officer who aspires to hold high command in war must understand clearly certain principles regarding the use of air power." Montgomery also believed that flexibility was the greatest asset of air power. This allowed it to be applied as a "battle-winning factor of the first importance." As well, he fully endorsed the air force view of centralized control: "Nothing could be more fatal to successful results than to dissipate the air resource into small packets placed under the control of army formation commanders, with each packet working on its own plan. The soldier must not expect, or wish, to exercise direct command over air striking forces." Montgomery concluded his discussion by stating that it was of prime importance for the army and air 1 Arthur Tedder, With Prejudice: The war memoirs of Marshal of the Royal Air Force, Lord Tedder (London: Cassell, 1966), p. -

The Pillars of American Grand Strategy in World War II by Tami Davis Biddle

Leveraging Strength: The Pillars of American Grand Strategy in World War II by Tami Davis Biddle Tami Davis Biddle is the Hoyt S. Vandenberg Chair of Aerospace Studies at the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle, PA. She is the author of Rhetoric and Reality in Air Warfare: The Evolution of British and American Thinking about Strategic Bombing, 1914–1945, and is at work on a new book titled, Taking Command: The United States at War, 1944–1945. This article is based on a lecture she delivered in March 2010 in The Hertog Program on Grand Strategy, jointly sponsored by Temple University’s Center for Force and Diplomacy, and FPRI. Abstract: This article argues that U.S. leaders navigated their way through World War II challenges in several important ways. These included: sustaining a functional civil-military relationship; mobilizing inside a democratic, capitalist paradigm; leveraging the moral high ground ceded to them by their enemies; cultivating their ongoing relationship with the British, and embra- cing a kind of adaptability and resiliency that facilitated their ability to learn from mistakes and take advantage of their enemies’ mistakes. ooking back on their World War II experience from the vantage point of the twenty-first century, Americans are struck, first of all, by the speed L with which everything was accomplished: armies were raised, fleets of planes and ships were built, setbacks were overcome, and great victories were won—all in a mere 45 months. Between December 1941 and August 1945, Americans faced extraordinary challenges and accepted responsibilities they had previously eschewed. -

The German Army, Vimy Ridge and the Elastic Defence in Depth in 1917

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 18, ISSUE 2 Studies “Lessons learned” in WWI: The German Army, Vimy Ridge and the Elastic Defence in Depth in 1917 Christian Stachelbeck The Battle of Arras in the spring of 1917 marked the beginning of the major allied offensives on the western front. The attack by the British 1st Army (Horne) and 3rd Army (Allenby) was intended to divert attention from the French main offensive under General Robert Nivelle at the Chemin des Dames (Nivelle Offensive). 1 The French commander-in-chief wanted to force the decisive breakthrough in the west. Between 9 and 12 April, the British had succeeded in penetrating the front across a width of 18 kilometres and advancing around six kilometres, while the Canadian corps (Byng), deployed for the first time in closed formation, seized the ridge near Vimy, which had been fiercely contested since late 1914.2 The success was paid for with the bloody loss of 1 On the German side, the battles at Arras between 2 April and 20 May 1917 were officially referred to as Schlacht bei Arras (Battle of Arras). In Canada, the term Battle of Vimy Ridge is commonly used for the initial phase of the battle. The seizure of Vimy ridge was a central objective of the offensive and was intended to secure the protection of the northern flank of the 3rd Army. 2 For detailed information on this, see: Jack Sheldon, The German Army on Vimy Ridge 1914-1917 (Barnsley: Pen&Sword Military, 2008), p. 8. Sheldon's book, however, is basically a largely indiscriminate succession of extensive quotes from regimental histories, diaries and force files from the Bavarian War Archive (Kriegsarchiv) in Munich. -

EHA Magazine Vol.3 No.3 September 2019

EHA MAGAZINE Engineering Heritage Australia Magazine Volume 3 No.3 September 2019 Engineering Heritage Australia Magazine ISSN 2206-0200 (Online) September 2019 This is a free magazine covering stories and news items about Volume 3 Number 3 industrial and engineering heritage in Australia and elsewhere. EDITOR: It is published online as a down-loadable PDF document for Margret Doring, FIEAust. CPEng. M.ICOMOS readers to view on screen or print their own copies. EA members and non-members on the EHA mailing lists will receive emails The Engineering Heritage Australia Magazine is notifying them of new issues, with a link to the relevant Engineers published by Engineers Australia’s National Australia website page. Committee for Engineering Heritage. Statements made or opinions expressed in the Magazine are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect CONTENTS the views of Engineers Australia. Editorial & Connections 3 Contact EHA by email at: The Electrification of Melbourne’s Railways 4 [email protected] or visit the website at: Gladesville Bridge 6 https://www.engineersaustralia.org.au/Communiti es-And-Groups/Special-Interest-Groups/Engineerin Lighting the Streets with Electricity 10 g-Heritage-Australia Honeysuckle Creek & the Moon Landings 14 Unsubscribe: If you do not wish to receive any The Beirut to Tripoli Railway 18 further material from Engineering Heritage Australia, contact EHA at : [email protected] “Wonders Never Cease” Subscribe: Readers who want to be added to the subscriber list can contact EHA via our email at : “100 Australian Engineering Achievements.” [email protected] Engineers Australia (EA) is celebrating its centenary year in 2019. -

Canadian Infantry Combat Training During the Second World War

SHARPENING THE SABRE: CANADIAN INFANTRY COMBAT TRAINING DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR By R. DANIEL PELLERIN BBA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2007 BA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2008 MA, University of Waterloo, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in History University of Ottawa Ottawa, Ontario, Canada © Raymond Daniel Ryan Pellerin, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii ABSTRACT “Sharpening the Sabre: Canadian Infantry Combat Training during the Second World War” Author: R. Daniel Pellerin Supervisor: Serge Marc Durflinger 2016 During the Second World War, training was the Canadian Army’s longest sustained activity. Aside from isolated engagements at Hong Kong and Dieppe, the Canadians did not fight in a protracted campaign until the invasion of Sicily in July 1943. The years that Canadian infantry units spent training in the United Kingdom were formative in the history of the Canadian Army. Despite what much of the historical literature has suggested, training succeeded in making the Canadian infantry capable of succeeding in battle against German forces. Canadian infantry training showed a definite progression towards professionalism and away from a pervasive prewar mentality that the infantry was a largely unskilled arm and that training infantrymen did not require special expertise. From 1939 to 1941, Canadian infantry training suffered from problems ranging from equipment shortages to poor senior leadership. In late 1941, the Canadians were introduced to a new method of training called “battle drill,” which broke tactical manoeuvres into simple movements, encouraged initiative among junior leaders, and greatly boosted the men’s morale. -

The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 Karl James University of Wollongong James, Karl, The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945, PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2005. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from University of Wollongong by Karl James, BA (Hons) School of History and Politics 2005 i CERTIFICATION I, Karl James, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, is wholly my work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Karl James 20 July 2005 ii Table of Contents Maps, List of Illustrations iv Abbreviations vi Conversion viii Abstract ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1 ‘We have got to play our part in it’. Australia’s land war until 1944. 15 2 ‘History written is history preserved’. History’s treatment of the Final Campaigns. 30 3 ‘Once the soldier had gone to war he looked for leadership’. The men of the II Australian Corps. 51 4 ‘Away to the north of Queensland, On the tropic shores of hell, Stand grimfaced men who watch and wait, For a future none can tell’. The campaign takes shape: Torokina and the Outer Islands. -

Zero Day Exploits and National Readiness for Cyber-Warfare

Nigerian Journal of Technology (NIJOTECH) Vol. 36, No. 4, October 2017, pp. 1174 – 1183 Copyright© Faculty of Engineering, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Print ISSN: 0331-8443, Electronic ISSN: 2467-8821 www.nijotech.com http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njt.v36i4.26 ZERO DAY EXPLOITS AND NATIONAL READINESS FOR CYBER-WARFARE A. E. Ibor* DEPT. OF COMPUTER SCIENCE, CROSS RIVER UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, CALABAR, CROSS RIVER STATE NIGERIA E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT A zero day vulnerability is an unknown exploit that divulges security flaws in software before such a flaw is publicly reported or announced. But how should a nation react to a zero day? This question is a concern for most national governments, and one that requires a systematic approach for its resolution. The securities of critical infrastructure of nations and states have been severally violated by cybercriminals. Nation-state espionage and the possible disruption and circumvention of the security of critical networks has been on the increase. Most of these violations are possible through detectable operational bypasses, which are rather ignored by security administrators. One common instance of a detectable operational bypass is the non-application of periodic security updates and upgrades from software and hardware vendors. Every software is not necessarily in its final state, and the application of periodic updates allow for the patching of vulnerable systems, making them to be secure enough to withstand an exploit. To have control over the security of critical national assets, a nation must be “cyber-ready” through the proper management of vulnerabilities and the deployment of the rightful technology in the cyberspace for hunting, detecting and preventing cyber-attacks and espionage. -

'Something Is Wrong with Our Army…' Command, Leadership & Italian

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 14, ISSUE 1, FALL 2011 Studies ‘Something is wrong with our army…’ Command, Leadership & Italian Military Failure in the First Libyan Campaign, 1940-41. Dr. Craig Stockings There is no question that the First Libyan Campaign of 1940-41 was an Italian military disaster of the highest order. Within hours of Mussolini’s declaration of war British troops began launching a series of very successful raids by air, sea and land in the North African theatre. Despite such early setbacks a long-anticipated Italian invasion of Egypt began on 13 September 1940. After three days of ponderous and costly advance, elements of the Italian 10th Army halted 95 kilometres into Egyptian territory and dug into a series of fortified camps southwest of the small coastal village of Sidi Barrani. From 9-11 December, these camps were attacked by Western Desert Force (WDF) in the opening stages of Operation Compass – the British counter-offensive against the Italian invasion. Italian troops not killed or captured in the rout that followed began a desperate and disjointed withdrawal back over the Libyan border, with the British in pursuit. The next significant engagement of the campaign was at the port-village Bardia, 30 kilometres inside Libya, in the first week of 1941. There the Australian 6 Division, having recently replaced 4 Indian Division as the infantry component of WDF (now renamed 13 Corps), broke the Italian fortress and its 40,000 defenders with few casualties. The feat was repeated at the port of Tobruk, deeper into Libya, when another 27,000 Italian prisoners were taken.