Etudes Helleniques Hellenic Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stratis Myrivilis (1890 - 1969), the Author of “The Mermaid Madonna”

Erasmus+ project: “Every Child Matters: refugees and immigrants in education” Daily Junior High School of Petra, Lesvos, Hellas TENDRING TECHNOLOGY COLLEGE, Essex, U.K., 9-13 October 2017 Our school in Greece! Junior High School of Petra (Lesvos, Hellas) Participant countries: England Hellas Italy Portugal Turkey Participant teachers: •Mr. Charalambos Kavouras, Ancient/Modern Greek teacher •Ms. Panayiota Thiveou, English teacher •Ms. Eleni Ververi, Ancient/Modern Greek teacher Participant students: •Alexandra Kalpaki, C Class (Greek Gymnasium) •Eirini Miftiou, C Class (Greek Gymnasium) Mobility Theme: “Cultures – influences of immigration on literature, music and arts” PART A A short biography of Stratis Myrivilis (1890 - 1969), the author of “The Mermaid Madonna” Stratis Myrivilis (1890–1969) “The Mermaid Madonna” Stratis Myrivilis (1890–1969), is a major figure in the literary history of the 20th century in Greece. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature three times. He is considered one of the best European antiwar writers. He enrolled at Athens University to study law. However, his university education was cut short when he volunteered to fight in the first Balkan War in 1912. He also fought on the Macedonian front in North Greece and in the Asia Minor Campaign which followed. PART B The “Mermaid Madonna” by Stratis Myrivilis - The story of the refugees of 1922 In 1949, Myrivilis’ novel “The Mermaid Madonna” was published. The title of the novel derives from the name of a white chapel in his hometown dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The tiny chapel is built on a rock in the picturesque fishing village of Skala Skamia, on the island of Lesvos. -

American School of Classical Studies at Athens Newsletter Index 1977-2012 the Index Is Geared Toward Subjects, Sites, and Major

American School of Classical Studies at Athens Newsletter Index 1977-2012 The index is geared toward subjects, sites, and major figures in the history of the School, and only the major subject of an article. Not every individual has a cross-entry: look for subject and site, first—entries that will tend to be more complete. Note: The symbol (F) next to an entry signifies the presence of a photograph of the subject. S = Spring [occasionally, Summer] Issue; F = Fall Issue; and W= Winter Issue, followed by the year and page number. Parentheses within subentries surround subsubentries, which would otherwise be indented and consume more space; this level of entry is separated by commas rather than semi-colons. When in doubt in a jungle of parentheses, refer to the right of the last semi-colon for the relevant subhead. Where this method becomes less effective, e.g., at “mega”-entries like the Gennadeion, typesetting devices like boldface and indentation have been added. Abbe, Mark (Wiener Travel Grant recipient): on roman sculpture in Corinth F10- 24 (F) Academy of Athens: admits H. Thompson F80-1 (F); gold medal to ASCSA S87- 4 (F) Acrocorinth: annual meeting report (R. Stroud) S88-5; sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone S88-5 (F). See also Corinth Acropolis (Athens): anniversary (300th) of bombardment observed F87-12; conservation measures, Erechtheion and Parthenon F84-1 (F), F88-7 (F), F91- 5 (F); exploration work of J.C. Wright S79-14 (F); Propylaia study, publication of S92-3 (F); reconstruction efforts, Parthenon (K.A. Schwab) S93-5 (F); restoration photos displayed at Fairfield University S04-4 (F);Temple of Athena Nike S99-5 (F) Adkins, Evelyn (Jameson Fellow): on school experience F11-13 Adossides, Alexander: tribute to S84-13 Aegean Fellows program (ARIT-ASCSA) S02-12 (F) Aesop’s Fables postcards: F87-15 After-Tea-Talks: description and ‘79 schedule F79-5; ‘80-‘81 report (P. -

Balkan Wars Between the Lines: Violence and Civilians in Macedonia, 1912-1918

ABSTRACT Title of Document: BALKAN WARS BETWEEN THE LINES: VIOLENCE AND CIVILIANS IN MACEDONIA, 1912-1918 Stefan Sotiris Papaioannou, Ph.D., 2012 Directed By: Professor John R. Lampe, Department of History This dissertation challenges the widely held view that there is something morbidly distinctive about violence in the Balkans. It subjects this notion to scrutiny by examining how inhabitants of the embattled region of Macedonia endured a particularly violent set of events: the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and the First World War. Making use of a variety of sources including archives located in the three countries that today share the region of Macedonia, the study reveals that members of this majority-Orthodox Christian civilian population were not inclined to perpetrate wartime violence against one another. Though they often identified with rival national camps, inhabitants of Macedonia were typically willing neither to kill their neighbors nor to die over those differences. They preferred to pursue priorities they considered more important, including economic advancement, education, and security of their properties, all of which were likely to be undermined by internecine violence. National armies from Balkan countries then adjacent to geographic Macedonia (Bulgaria, Greece, and Serbia) and their associated paramilitary forces were instead the perpetrators of violence against civilians. In these violent activities they were joined by armies from Western and Central Europe during the First World War. Contrary to existing military and diplomatic histories that emphasize continuities between the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and the First World War, this primarily social history reveals that the nature of abuses committed against civilians changed rapidly during this six-year period. -

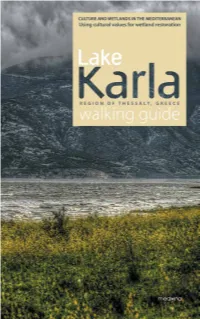

ENG-Karla-Web-Extra-Low.Pdf

231 CULTURE AND WETLANDS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Using cultural values for wetland restoration 2 CULTURE AND WETLANDS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Using cultural values for wetland restoration Lake Karla walking guide Mediterranean Institute for Nature and Anthropos Med-INA, Athens 2014 3 Edited by Stefanos Dodouras, Irini Lyratzaki and Thymio Papayannis Contributors: Charalampos Alexandrou, Chairman of Kerasia Cultural Association Maria Chamoglou, Ichthyologist, Managing Authority of the Eco-Development Area of Karla-Mavrovouni-Kefalovryso-Velestino Antonia Chasioti, Chairwoman of the Local Council of Kerasia Stefanos Dodouras, Sustainability Consultant PhD, Med-INA Andromachi Economou, Senior Researcher, Hellenic Folklore Research Centre, Academy of Athens Vana Georgala, Architect-Planner, Municipality of Rigas Feraios Ifigeneia Kagkalou, Dr of Biology, Polytechnic School, Department of Civil Engineering, Democritus University of Thrace Vasilis Kanakoudis, Assistant Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Thessaly Thanos Kastritis, Conservation Manager, Hellenic Ornithological Society Irini Lyratzaki, Anthropologist, Med-INA Maria Magaliou-Pallikari, Forester, Municipality of Rigas Feraios Sofia Margoni, Geomorphologist PhD, School of Engineering, University of Thessaly Antikleia Moudrea-Agrafioti, Archaeologist, Department of History, Archaeology and Social Anthropology, University of Thessaly Triantafyllos Papaioannou, Chairman of the Local Council of Kanalia Aikaterini Polymerou-Kamilaki, Director of the Hellenic Folklore Research -

{PDF EPUB} Life in the Tomb by Stratis Myrivilis Stratis Myrivilis

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Life in the Tomb by Stratis Myrivilis Stratis Myrivilis. Efstratios Stamatopoulos [lower-alpha 1] (30 June 1890 – 19 July 1969) was a Greek writer. He is known for writing novels, novellas, and short stories under the pseudonym Stratis Myrivilis . [lower-alpha 2] He is associated with the "Generation of the '30s". [1] He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature three times (1960, 1962, 1963). [2] Contents. Biography [ edit | edit source ] Myrivilis was born in the village of Sykaminea (Συκαμινέα), also known as Sykamia (Συκαμιά), on the north coast of the island of Lesbos (then part of the Ottoman Empire), in 1890. [3] There he spent his childhood years until, in 1905, he was sent to the town of Mytilene to study at the Gymnasium. In 1910 he completed his secondary education and took a post as a village schoolmaster, but gave that up after one year and enrolled at Athens University to study law. However, his university education was cut short when he volunteered to fight in the First Balkan War in 1912. After the Balkan Wars, he returned home to a Lesbos free from Turkish rule and united with the motherland Greece. There he made a name for himself as a columnist and as a writer of poetry and fiction. He published his first book in 1915: a set of six short stories collected together under the general title of Red Stories . In World War I, Myrivilis saw active service in the army of Eleftherios Venizelos' breakaway government on the Macedonian front and also in the Asia Minor Campaign which followed. -

Editorial Board

EDITORIAL BOARD: Rismag Gordeziani – Editor-in-Chief Dimitris Angelatos (Nicosia) Valeri Asatiani Irine Darchia Riccardo Di Donato (Pisa) Tina Dolidze Levan Gordeziani Sophie Shamanidi Nana Tonia Jürgen Werner (Berlin) Tamara Cheishvili – Executive Secretary fazisi 11, 2008 ivane javaxiSvilis saxelobis Tbilisis saxelmwifo universitetis klasikuri filologiis, bizantinistikisa da neogrecistikis institutis berZnuli da romauli Studiebi © programa ‘logosi’, 2008 ISSN 1512-1046 EDITORIAL NOTE Those who wish to contribute to the journal Phasis are requested to submit an electronic version and a hard copy of their paper (in Microsoft Word for Windows format, font Book Antiqua). If there are any special characters in the paper, please indicate them on the left margin next to their respective lines. Notes must be continuously numbered in 1, 2, 3 … format and appear as footnotes. The following way of citing bibliography is suggested: In the case of a periodical or of a collection of papers: the name of the au- thor (initials and full surname), the title of the paper, the title of the pe- riodical, number, year, pages (without p.); In the case of monographs: the name of the author (initials and full surname), the title of the work, publisher (name and city), year, pages (without p.). Papers must be submitted in the following languages: English, French, German, Italian and Modern Greek. Accepted papers will be published in the next volume. Each contributor will receive one copy of the volume. Please send us your exact wherea- bouts: address, telephone number, fax number, e-mail. Our address: Institute of Classical, Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University 13 Chavchavadze ave. -

Gecikmiş MODERNLİK VE ESTETIK KÜLTÜR Milli Edebiyatın İcat Edilişi Gregory Jusdanis, Kuzey Yunanistan'da Doğdu

• • GECIKMIS MODERNLİK • VE ESTETIK •• •• KULTUR Milli Edebiyatın İcat Edilişi � metis Gregory Jusdanis GECiKMiŞ MODERNLİK VE ESTETIK KÜLTÜR Milli Edebiyatın İcat Edilişi Gregory Jusdanis, Kuzey Yunanistan'da doğdu. On yaşın dayken ailesiyle birlikte Kanada'ya yerleşti. Üniversite eğitimini burada yaptıktan sonra eğitimini Almanya, İn giltere ve ABD'de sürdürdü. Halen Ohio State University' de Yunan edebiyatı ve edebiyat kuramı dersleri veren, milliyetçilik ve kültür üzerine çalışmalar yürüten Jusda nis, bu kitabından önce The Poetics of Cavafyadlı araştır masını yayımlamıştır. Metis Yayınlan İpek Sokak 9, 80060 Beyoğlu, İstanbul GECİKMİŞ MODERNLİK VE ESTETİK KÜL TÜR Milli Edebiyatın İcat Edilişi Gregory Jusdanis Özgün Adı: Belated Modemity and Aesthetic Culture Inventing National Literature © ı 991, The Regents ofthe University ofMinnesota ©Metis Yayın1an, 1997 Birinci Basım: Mayıs 1998 Yayına Hazırlayan: Beril Eyüboğ1u Kapak Resmi: Avni Lifij'in Elem Günü tablosundan detay ( 1917, Ankara Resim ve Heyke1 Müzesi) Kapak Tasarımı: Semih Sökmen Dizgi ve Baskı Öncesi Hazırlık: Sedat Ateş Film: Doruk Grafik Kapak ve İç Baskı: Yaylacık Matbaacılık Ltd. Cilt: Sistem Mücellithanesi ISBN 975-342-186-9 GREGORY JUSDANIS GECiKMiŞ MODERNLİK VE ES TETİK KULTUR• • • • Milli Edebiyatın İcat Edilişi Çeviren: TUNCAYBİRKAN METiS YAYINLARI Içindekiler Teşekkürler 7 Giriş 9 Milli Kültür Olarak Eleştiri 18 Imparatorluktan Ulus-Devlete: Yunanlılar'ın Beklentileri 35 Bir Kanonun Oluşumu: Kendilerine Ait Bir Edebiyat 79 Sanatın Ortaya Çıkışı ve Modernleşmenin Başarısızlıkları 134 Kamusal Kültür Mekanları 179 Sonsöz: Hikayelerin Sonu mu? 227 Kaynakça 232 Julian için Teşekkürler � İlerideki sayfalarda sık sık bu çalışmaya edebiyatların tarihsel olarak ortaya çıkışına dair kolektif bir araştırmanın bir parçası olarak bakılma sı gerektiğini belirtiyorum. Bu kişisel olarak da doğru. Birçok arkadaşı ma, meslektaşıma ve bazı kurumlara çok şey borçluyum. -

Centre for Hellenic Studies

Centre for Hellenic Studies Newsletter 30 December 2019 Director’s Report The year 2019 started off strong with a fascinating, well-attended Biography of a Modern Nation, will help shape the many ways Runciman Lecture, given by Professor Richard P. Martin in which Greece and the Greek diaspora will be celebrating the (Stanford University). Over the summer, the Arts & Humanities bicentenary of the Greek Revolution in 2021. Research Institute (AHRI) and CHS collaborated closely to A student group visited Athens and Rhodes during the last week overhaul the Centre’s webpages and to upload another rich events of October 2019. Their trip was generously sponsored by the list for the new academic year. Our autumn semester started with Jamie Rumble Memorial Fund. Pictures from their trip and their a celebration. On 30 September colleagues and CHS friends and many adventures grace this newsletter. One of the highlights of donors came out in strong numbers to congratulate Emeritus the tour was a guided visit of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Koraes Professor Roderick Beaton on the special distinction Cultural Center. Also exciting was their meeting, in a classroom he received a couple of weeks earlier (on 9 September): in a setting, with students and peers from the University of the Aegean special award ceremony held at the presidential mansion, Mr Rhodes campus. The trip was an intrinsic part of our newly Prokopis Pavlopoulos, President of the Hellenic Republic, designed BA and MA module, ‘Engaging Greece: Experiencing bestowed on him the Medal of the Commander of the Order the Past and Responding to the Present’. -

The Crisis Years (1922-1927)

CHAPTER THREE: The Crisis Years (1922-1927) 'I will write a sad ballad to the uncelebrated poets. There are those who take their place in history, and there are those who make history. It is the latter I honour.' (Terzakis 1987: 76) I Bakhtin's dialogic approach can provide a valuable perspective on the biographical narrative, highlighting the multiplicity of situated sites within it, the corporeal nature of subjectivity and memory, and the writer-biographer's location in the writing process. In this chapter I have approached the narrative by constructing a broad historical and literary framework of the period and by exploring Alekos Doukas' letters and manuscript's in relation to the contexts of his locations. I have used Bakhtin's concept of the 'chronotope' in both its literary and extra- literary sense to historically position the texts under scrutiny. Genre is given attention as a 'master category of dialogism' which allows us to read the texts in relation to the changing genres of the period (Holquist 1990: 144). This offers biographical discourse a generic analysis of texts through a diachronic perspective and interplay of textual and non-textual mediations. The biographical self is not sculptured in a vacuum but in direct relation to others, much as a hologram appears in three-dimensional space through its placement within a surrounding field. Far from being a simple interaction of two fixed entities, the self/other relationship is dynamic and contested, giving rise to distinctive identities which are never entirely stable or static (Holquist 1990: 135)*. This relationship is another aspect of intertextuality, and a literary biography is nothing if not an exploration of this endless web of intertextual dialogue. -

Chalkou, Maria (2008) Towards the Creation of 'Quality' Greek National Cinema in the 1960S

Chalkou, Maria (2008) Towards the creation of 'quality' Greek national cinema in the 1960s. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1882/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] TOWARDS THE CREATION OF ‘QUALITY’ GREEK NATIONAL CINEMA IN THE 1960S by Maria Chalkou Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD Department of Theatre, Film & Television Studies Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow Supported by the State Scholarship Foundation of Greece (I.K.Y.) 6 December 2008 CONTENTS ABSTRACT (1) INTRODUCTION (2-11) 1. THE ORIGINS OF NEK: SOCIOPOLITICAL, CULTURAL, LEGISLATIVE AND CINEMATIC FRAMEWORK, AND THE NATIONAL CINEMA DEBATE (12-62) 1.1 The 1960s: the sociopolitical and cultural framework (13-20) 1.2 The commercial film industry and the development of two coexisting and intersecting film cultures (20-27) 1.3 The state’s institutional and financial involvement in cinema: the beginning of a new direction (27-33) 1.4 The public debate over a ‘valued’ Greek national cinema (34-63) a. -

Greek Historiography and Slav-Macedonian National Identity

GREEK HISTORIOGRAPHY AND SLAV-MACEDONIAN NATIONAL IDENTITY In his celebrated novel Η ζωή εν τάφω [Life in a tomb] (1954 edition), Greek author Stratis Myrivilis has the protagonist briefly stay in a village in the region of Macedonia during World War I. The peasants: …spoke a language understood both by Serbs and Bulgarians. The first they hate because they torment them and treat them as if they were Bulgarians; and they [also] hate the Bulgarians because they took their children to the war. Us [Greeks] they accept with some sympathetic curiosity, only because we are the genuine moral subjects of the…Ecumenical Patriarch.1 It is fair to assume that this encounter was with people that today most Greeks would have identified as Slav-Macedonians. The existence, formation and mutations of their national identity have posed an interpretative challenge to Greek scholars and proved a consistently controversial topic. Since the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) declared independence in September 1991, the name dispute has added a further layer of often emotional complexity to bilateral arguments and understandings of identity.2 Over the past century, a mainstream narrative has emerged in Greek historiography concerning when and how Slav-Macedonian national 1 Stratis Myrivilis, Η ζωή εν τάφω [Life in a tomb], Athens: Estia, n.d., p. 227; my translation. This passage is taken from the seventh and final 1954 edition. In the novel’s first edition, published in 1924, the above-cited passage is to be found in a version that is similar in essence but perhaps somewhat rougher in language. -

Downloaded for Personal Non‐Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

Lemos, Anastasia Aglaia (2019) Aspects of the literatures of the Turkish war of independence and the Greek Asia Minor disaster. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/30967 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. ASPECTS OF THE LITERATURES OF THE TURKISH WAR OF INDEPENDENCE AND THE GREEK ASIA MINOR DISASTER Anastasia Aglaia Lemos Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2018 Department of the Languages and Cultures of the Near and Middle East SOAS, University of London 1 ABSTRACT The thesis examines literary works in Greek and Turkish inspired by the war of 1919- 1922 and the subsequent exchange of populations, the most critical years in the recent life of both nations. It focuses on the early period, particularly the works of Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu and Halide Edip Adıvar in Turkey and Elias Venezis in Greece. It seeks to show the way themes were selected and then used or adapted to reflect more contemporary concerns.