Holding Fire: Security Force Allegiance During Nonviolent Uprisings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements

BETWEEN MAO AND GANDHI: STRATEGIES OF VIOLENCE AND NONVIOLENCE IN REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENTS A thesis Presented to the Faculty of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy by CHES THURBER In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2015 Dissertation Committee: Richard Shultz, Chair H. Zeynep Bulutgil Erica Chenoweth CHES THURBER 104 E. Main St. #2, Gloucester, MA 02155 [email protected] | (617) 710-2617 DOB: September 21, 1982 in New York, NY, USA EDUCATION Tufts University, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy PH.D. | International Relations (2015) Dissertation: “Between Mao and Gandhi: Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements” Committee: Richard Shultz, Zeynep Bulutgil, Erica Chenoweth M.A.L.D. | International Relations (2010) Middlebury College B.A. | International Studies (summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, 2004) ACADEMIC University of Chicago APPOINTMENTS Postdoctoral Fellow, Chicago Project on Security and Terrorism (Beginning Aug. 1, 2015) Program on Political Violence Harvard University Research Fellow, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs (2014-2015) International Security Program PUBLICATIONS “Militias as Sociopolitical Movements: Lessons from Iraq’s Armed Shia Groups" in Small Wars and Insurgencies 25, nos. 5-6 (October 2014): 900-923. Review of The Maoist Insurgency in Nepal: Revolution in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Mahendra Lawoti and Anuk K. Pahari, in Himalaya 34, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 148-150. “A Step Short of the Bomb: Explaining the Strategy of Nuclear Hedging” in Journal of Public and International Affairs (2011). “From Coexistence to Cleansing: The Rise of Sectarian Violence in Baghdad, 2003-2006” in al-Nakhlah: Journal of Southwest Asia and Islamic Civilization (March 2011). -

For Free Distribution

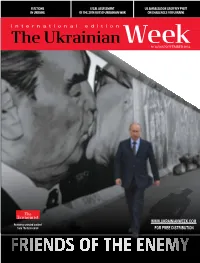

ELECTIONS LeGAL ASSESSMENT US AMBASSADOR GeOFFREY PYATT IN UKRAINE OF THE 2014 RuSSO-UKRAINIAN WAR ON CHALLENGES FOR UKRAINE № 14 (80) NOVEMBER 2014 WWW.UKRAINIANWEEK.COM Featuring selected content from The Economist FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION |CONTENTS BRIEFING Lobbymocracy: Ukraine does not have Rapid Response Elections: The victory adequate support in the West, either in of pro-European parties must be put political circles, or among experts. The to work toward rapid and irreversible situation with the mass media and civil reforms. Otherwise it will quickly turn society is slightly better into an equally impressive defeat 28 4 Leonidas Donskis: An imagined dialogue on several clichés and misperceptions POLITICS 30 Starting a New Life, Voting as Before: Elections in the Donbas NEIGHBOURS 8 Russia’s gangster regime – the real story Broken Democracy on the Frontline: “Unhappy, poorly dressed people, 31 mostly elderly, trudged to the polls Karen Dawisha, the author of Putin’s to cast their votes for one of the Kleptocracy, on the loyalty of the Russian richest people in Donetsk Oblast” President’s team, the role of Ukraine in his grip 10 on power, and on Russia’s money in Europe Poroshenko’s Blunders: 32 The President’s bloc is painfully The Bear, Master of itsT aiga Lair: reminiscent of previous political Russians support the Kremlin’s path towards self-isolation projects that failed bitterly and confrontation with the West, ignoring the fact that they don’t have a realistic chance of becoming another 12 pole of influence in the world 2014 -

Georgia: What Now?

GEORGIA: WHAT NOW? 3 December 2003 Europe Report N°151 Tbilisi/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................. 2 A. HISTORY ...............................................................................................................................2 B. GEOPOLITICS ........................................................................................................................3 1. External Players .........................................................................................................4 2. Why Georgia Matters.................................................................................................5 III. WHAT LED TO THE REVOLUTION........................................................................ 6 A. ELECTIONS – FREE AND FAIR? ..............................................................................................8 B. ELECTION DAY AND AFTER ..................................................................................................9 IV. ENSURING STATE CONTINUITY .......................................................................... 12 A. STABILITY IN THE TRANSITION PERIOD ...............................................................................12 B. THE PRO-SHEVARDNADZE -

Report No. 2: the Instigators Are Getting Away

The Gongadze Inquiry An investigation into the failure of legal and judicial processes in the case of Gyorgy Gongadze Supported by: • The International Federation of Journalists • The Institute of Mass Information • The National Union of Journalists of the UK and Ireland • The Gongadze Foundation Report no. 2: The instigators are getting away 1 Introduction This second report on the case of Gyorgy Gongadze, commissioned by the International Federation of Journalists, the Institute of Mass Information (Kyiv), the Gongadze Foundation and the National Union of Journalists of the UK and Ireland, updates our first report published in January 2005.1 It reviews developments in the investigation of the case between January and September 2005. Our main conclusion, set out in the last section, is that the investigation of the process by which Gongadze’s murder was ordered has suffered serious setbacks. Progress has been made in bringing to trial interior ministry officers who allegedly participated in Gongadze’s kidnap, and were present when he was murdered. But the investigation’s failures with respect to the links between these direct perpetrators and those who ordered the murder are so blatant and numerous that they can most likely be explained as the result of continued political interference and resistance. Senior political figures have stated publicly that the instigators of Gongadze’s murder are known to investigators, but no details have been made public; this has left the impression that these statements were part of the “public relations management” of the investigation, which was meanwhile directing its focus away from the instigators. Our most serious concerns relate to the case of General Olexiy Pukach, who was named by the general prosecutor’s office as the ringleader of the gang that killed Gongadze. -

Canvas Core Curriculum: a Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle

CANVAS CORE CURRICULUM: A GUIDE TO EFFECTIVE NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE STUDENTS BOOK by CANVAS printed and published in Serbia 2007 CANVAS Curriculum Introduction Before you is a wealth of knowledge about the planning, conduct, and Srdja Popovic, Slobodan Djinovic, Andrej Milivojevic, Hardy Merriman evaluation of strategic nonviolent conflict. This curriculum guide will be a and Ivan Marovic valuable companion to new and experienced activists, as well as to others who wish to learn about this subject. CANVAS Core Curriculum: A Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle Copyright 2007 by CANVAS. All rights reserved. The authors combine classic insights about nonviolent conflict with new ideas based on recent experience. The result is a synthesis that pushes the Published in Serbia, 2007. limits of what we thought nonviolent strategies were capable of achieving. The material covered includes time-tested analyses of power, different ISBN 978-86-7596-087-4 methods of nonviolent action, and ways to create a strategic plan for developing and mobilizing a movement. In addition, the authors include new material about how to: Publisher: Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS) • chart a movement’s history and progress (Chapter 8) Masarikova 5/ XIII, Belgrade, Serbia, www.canvasopedia.org • use marketing, branding, and effective communication techniques in a movement (Chapters 9 and 10) Graphic design and illustrations: Ana Djordjevic • address the effects of fear on a movement’s members (Chapter 13) • develop security measures within a movement (Chapter 14) Photo on cover: Igor Jeremic • manage a movement’s material resources, human resources, and time (Advanced Chapters 2-4) Throughout these topics, the authors emphasize pragmatic learning and draw on their own experience applying these ideas in their own struggles. -

Contemporary Art in the Regions of Russia: Global Trends and Local Projects

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 10 (2016 9) 2413-2426 ~ ~ ~ УДК 7.01 Contemporary Art in the Regions of Russia: Global Trends and Local Projects Dmitrii V. Galkin* and Anastasiia Iu. Kuklina National Research Tomsk State University 36 Lenina Str., Tomsk, 634050, Russia Received 21.04.2016, received in revised form 09.06.2016, accepted 19.08.2016 The authors deal with the problem of the development of contemporary art in the regions of Russia in the context of global projects and institutions, establishing ‘the rules of the game’ in the field of contemporary culture. The article considers the experience of working with contemporary art within the framework of the National Centre for Contemporary Arts and other organizations. So-called Siberian ironic conceptualism is considered as an example of original regional aesthetics. The article concludes that the alleged problem can be solved in the framework of specific exhibition projects and curatorial decisions, which aim at finding different forms of meetings (dialogue, conflict, addition) of a regional identity and global trends. Keywords: contemporary art, National Center for Contemporary Arts, curatorial activities, regional art. This article was prepared with the support of the Siberian Branch of the National Centre for Contemporary Arts. DOI: 10.17516/1997-1370-2016-9-10-2413-2426. Research area: art history. The growing interest of researchers and also intends to open a profile branch in Moscow. the public in the dynamic trends and issues But this is an example of the past three years. of contemporary art in Russia is inextricably There are more historically important and long- linked with the development of various projects standing examples. -

For Free Distribution

INTERNATIONAL PAGE EU AMBASSADOR TEIXEIRA PAGE IVAN MARCHUK: PAGE OPINION ON POLITICAL ON SCANDALOUS TRIALS A GREAT PAINTER INSPIRED PERSECUTION IN UKRAINE 10 AND THE ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT 16 BY HIS HOMELAND 42 № 9 (21) OCTOBER 2011 EUROPE MUST ACT NOW! www.ukrainianweek.com for free distribution featuring selected content from the economist |contents briefing focus PoLitics Europe Must The Collapse of Justice Damon Wilson Act Now! Lawyer Valentyna Telychenko on how Ukraine can The triangle talks about the cases against Yulia improve its image of Ukraine, Tymoshenko, Leonid Kuchma, Russia and the EU and Oleksiy Pukach who killed journalist Gongadze 4 6 10 David Kramer Steven Pifer Tango for Two and Freedom on official Kyiv Jose Manuel Pinto Teixeira House: We running out of on how the scandalous will continue room to maneuver trials in Ukraine can affect to tell the in the international Association Agreement truth arena prospects 12 14 16 neighbours economics Time to Shove Off Greek Consequences War and Myth The Soviet Union Ratification of the The real roots of was undermined by Association Agreement Ukraine’s energy stagnation and a sense of and FTA will depend dependence go back hopelessness. Is the same on whether political to the oligarchs thing happening again? repression stops 18 22 24 investigation society You’d Rather Be Dead Tour de Ukraine Who Is Scared While pharmaceutical Ukrainians switch of Ukrainian Hackers? groups fight for the to bicycles, pushing Ukrainian market, Ukraine’s supply local authorities to cybercriminals -

Presidential Election in Ukraine Implications for the Ukrainian Transition Presidential Election in Ukraine Implications for the Ukrainian Transition

Helmut Kurth/Iris Kempe (Ed.) PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION IN UKRAINE IMPLICATIONS FOR THE UKRAINIAN TRANSITION PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION IN UKRAINE IMPLICATIONS FOR THE UKRAINIAN TRANSITION KIEV – 2004 The following texts are preliminary versions. Necessary corrections and updates will be undertaken once the results of the election process are final. These preliminary versions are not for quotation or citation, and may only be used with the express written consent of the authors. CONTENTS Preface ................................................................................. 5 Timm Beichelt/Rostyslav Pavlenko Presidential Election and Constitutional Reforms in Ukraine ............................................................................ 7 Olaf Hillenbrand Consensus-Building and Good Governance – a Framework for Democratic Transition ........................... 44 Oleksandr Dergachov Formation of Democratic Consensus and Good Governance ....................................................... 71 Oleksandr Sushko/Oles Lisnychuk The 2004 Presidential Campaign as a Sign of Political Evolution in Ukraine....................................... 87 Iris Kempe/Iryna Solonenko International Orientation and Foreign Support of the Presidential Elections ............................................ 107 5 Preface Long before Kiev’s Independence Square became a sea of orange, it was clear to close observers that the presidential election in 2004 would not only be extremely close and hard fought, but also decisive for the country’s future development. Discussions -

Extensions of Remarks

23678 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS September 13, 1988 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS CHEMICAL GENOCIDE OF White House also accepted with indecent stroyed thousands of Kurdish villages and KURDS haste an Iraqi apology for the attack on the resettled as many of the Kurds in Arab USS Stark, which killed 37 American serv dominated regions as they could. After the icemen. In its grudge match with Iran, the Iran-Iraq war erupted in 1980, the surviving HON. STENY H. HOYER Reagan administration visibly tilted to Kurdish fighters threw in their lot with Iraq's side-and at a high price. Tehran. OF MARYLAND But now Washington appears either This time it is a truce with the ayatollahs IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES unable or unwilling to use the leverage it that has enabled Iraq to have another go at Tuesday, September 13, 1988 said it was obtaining to help the Kurds or removing the Kurds from their homelands, push the Iraqis to drop the hard-line posi with the new wrinkle of poison gas thrown Mr. HOYER. Mr. Speaker, two articles ap tions that have driven the negotiations on in. This time Hussein's intention of depopu peared in the Washington Post and the New ending the Iran-Iraq war into deadlock. lating Kurdistan may be within his grasp. York Times this week that I would like to Secretary of State George Shultz has It is unthinkable that he will benefit once given several recent speeches mixing elo submit for the RECORD. The thrust of both is again from official American indifference quence with hand-wringing about the hor and/or impotence that will be justified in clear. -

Explaining Foreign Policy Change in Transitional States

Explaining Foreign Policy Change in Transitional States: A Case Study of Ukraine between Two Revolutions By © 2017 Lidiya Zubytska M.A., University of Notre Dame, 2004 B.A., Ivan Franko National University of L’viv, 2002 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Political Science and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Mariya Omelicheva Robert Rohrschneider Nazli Avdan Steven Maynard-Moody Erik Herron Date Defended: 24 July 2017 The dissertation committee for Lidiya Zubytska certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Explaining Foreign Policy Change in Transitional States: A Case Study of Ukraine between Two Revolutions Chair: Mariya Omelicheva Date Approved: 24 July 2017 ii ABSTRACT Over the span of a decade, Ukraine saw two revolutions that rocked its political and social life to the very core. The Orange revolution of 2004, a watershed event in the post-Soviet history of East European states, reversed the authoritarian trend in the country and proclaimed its course for democracy and integration with the European Union. However, reforms and electoral promises of the revolutionary leaders quickly turned into shambles, and instead another pro- Russian authoritarian leader consolidated power. As Ukrainian political elites vacillated between closer ties with the EU to its west and the Russian Federation to its east, the 2014 Revolution of Dignity rose again to defend the European future for Ukraine. In this work, I investigate the driving forces shaping foreign policymaking in Ukraine during these years. I posit that it was precisely because such policies were shaped in an uncertain post-revolutionary transitional political environment that we are able to see seemingly contradictory shifts in Ukraine’s relations with the EU and Russia. -

Museological Unconscious VICTOR TUPITSYN Introduction by Susan Buck-Morss and Victor Tupitsyn the Museological Unconscious

The Museological Unconscious VICTOR TUPITSYN introduction by Susan Buck-Morss and Victor Tupitsyn The Museological Unconscious VICTOR TUPITSYN The Museological Unconscious VICTOR TUPITSYN Communal (Post)Modernism in Russia THE MIT PRESS CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS LONDON, ENGLAND © 2009 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please email special_sales@ mitpress.mit .edu or write to Special Sales Department, The MIT Press, 55 Hayward Street, Cambridge, MA 02142. This book was set in Sabon and Univers by Graphic Composition, Inc., Bogart, Georgia. Printed and bound in Spain. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tupitsyn, Viktor, 1945– The museological unconscious : communal (post) modernism in Russia / Victor Tupitsyn. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-20173-5 (hard cover : alk. paper) 1. Avant-garde (Aesthetics)—Russia (Federation) 2. Dissident art—Russia (Federation) 3. Art and state— Russia (Federation) 4. Art, Russian—20th century. 5. Art, Russian—21st century. I. Title. N6988.5.A83T87 2009 709.47’09045—dc22 2008031026 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Margarita CONTENTS PREFACE ix 1 Civitas Solis: Ghetto as Paradise 13 INTRODUCTION 1 2 Communal (Post)Modernism: 33 SUSAN BUCK- MORSS A Short History IN CONVERSATION 3 Moscow Communal Conceptualism 101 WITH VICTOR TUPITSYN 4 Icons of Iconoclasm 123 5 The Sun without a Muzzle 145 6 If I Were a Woman 169 7 Pushmi- pullyu: 187 St. -

Human Rights in Ukraine – 2005

HUMAN RIGHTS IN UKRAINE – 2005 HUMAN RIGHTS ORGANIZATIONS REPORT UKRAINIAN HELSINKI HUMAN RIGHTS UNION KHARKIV HUMAN RIGHTS PROTECTION GROUP KHARKIV «PRAVA LUDYNY» 2006 1 BBK 67.9(4) H68 In preparing the cover, the work of Alex Savransky «Freedom is on the march» was used Designer Boris Zakharov Editors Yevgeny Zakharov, Irina Rapp, Volodymyr Yavorsky Translator Halya Coynash The book is published with the assistance of the International Renaissance Foundation and the Democracy Fund of the U.S. Embassy, Kyiv The views of the authors do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Government Human Rights in Ukraine – 2005. Report by Human Rights Organizations. / Editors H68 Y.Zakharov, I.Rapp, V.Yavorsky / Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group – Kharkiv: Prava Ludyny, 2006. – 328 p. ISBN 966-8919-08-4. This book considers the human rights situation in Ukraine during 2005 and is based on studies by various non-governmental human rights organizations and specialists in this area. The first part gives a general assessment of state policy with regard to human rights in 2005, while in the second part each unit concentrates on identifying and analysing violations of specific rights in 2005, as well as discussing any positive moves which were made in protecting the given rights. Current legislation which encour- ages infringements of rights and freedoms is also analyzed, together with draft laws which could change the situation. The conclusions of the research contain recommendations for eliminating