Report No. 2: the Instigators Are Getting Away

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Justice for Journalists in Ukraine, Belarus and Russia September 2011

No Justice for Journalists in Ukraine, Belarus and Russia September 2011 ARTICLE 19 Free Word Centre 60 Farringdon Road London EC1R 3GA United Kingdom Tel: +44 20 7324 2500 Fax: +44 20 7490 0566 E-mail: [email protected] www.article19.org International Media Support (IMS) Nørregarde 18, 2nd floor 1165 Copenhagen K Denmark Tel: +45 88 32 7000 Fax: +45 33 12 0099 E-mail: [email protected] www.i-m-s.dk ISBN: 978-1-906586-27-0 © ARTICLE 19 and International Media Support (IMS), London and Copenhagen, August 2011 This work is provided under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 2.5 licence. You are free to copy, distribute and display this work and to make derivative works, provided you: 1) give credit to ARTICLE 19 and International Media Support (IMS); 2) do not use this work for commercial purposes; 3) distribute any works derived from this publication under a licence identical to this one. To access the full legal text of this licence, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ legalcode. ARTICLE 19 and International Media Support (IMS) would appreciate receiving a copy of any materials in which information from this report is used. This report was written and published within the framework of a project supported by the International Media Support (IMS) Media and Democracy Programme for Central and Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. It was compiled and written by Nathalie Losekoot, Senior Programme Officer for Europe at ARTICLE 19 and reviewed by JUDr. Barbora Bukovskà, Senior Director for Law at ARTICLE 19 and Jane Møller Larsen, Programme Coordinator for the Media and Democracy Unit at International Media Support (IMS). -

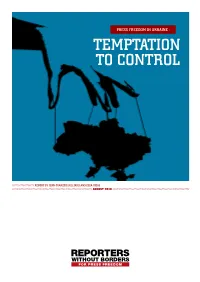

Temptation to Control

PrESS frEEDOM IN UKRAINE : TEMPTATION TO CONTROL ////////////////// REPORT BY JEAN-FRANÇOIS JULLIARD AND ELSA VIDAL ////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// AUGUST 2010 /////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// PRESS FREEDOM: REPORT OF FACT-FINDING VISIT TO UKRAINE ///////////////////////////////////////////////////////// 2 Natalia Negrey / public action at Mykhaylivska Square in Kiev in November of 2009 Many journalists, free speech organisations and opposition parliamentarians are concerned to see the government becoming more and more remote and impenetrable. During a public meeting on 20 July between Reporters Without Borders and members of the Ukrainian parliament’s Committee of Enquiry into Freedom of Expression, parliamentarian Andrei Shevchenko deplored not only the increase in press freedom violations but also, and above all, the disturbing and challenging lack of reaction from the government. The data gathered by the organisation in the course of its monitoring of Ukraine confirms that there has been a significant increase in reports of press freedom violations since Viktor Yanukovych’s election as president in February. LEGISlaTIVE ISSUES The government’s desire to control journalists is reflected in the legislative domain. Reporters Without Borders visited Ukraine from 19 to 21 July in order to accomplish The Commission for Establishing Freedom the first part of an evaluation of the press freedom situation. of Expression, which was attached to the presi- It met national and local media representatives, members of press freedom dent’s office, was dissolved without explanation NGOs (Stop Censorship, Telekritika, SNUJ and IMI), ruling party and opposition parliamentarians and representatives of the prosecutor-general’s office. on 2 April by a decree posted on the president’s At the end of this initial visit, Reporters Without Borders gave a news conference website on 9 April. -

For Free Distribution

INTERNATIONAL PAGE EU AMBASSADOR TEIXEIRA PAGE IVAN MARCHUK: PAGE OPINION ON POLITICAL ON SCANDALOUS TRIALS A GREAT PAINTER INSPIRED PERSECUTION IN UKRAINE 10 AND THE ASSOCIATION AGREEMENT 16 BY HIS HOMELAND 42 № 9 (21) OCTOBER 2011 EUROPE MUST ACT NOW! www.ukrainianweek.com for free distribution featuring selected content from the economist |contents briefing focus PoLitics Europe Must The Collapse of Justice Damon Wilson Act Now! Lawyer Valentyna Telychenko on how Ukraine can The triangle talks about the cases against Yulia improve its image of Ukraine, Tymoshenko, Leonid Kuchma, Russia and the EU and Oleksiy Pukach who killed journalist Gongadze 4 6 10 David Kramer Steven Pifer Tango for Two and Freedom on official Kyiv Jose Manuel Pinto Teixeira House: We running out of on how the scandalous will continue room to maneuver trials in Ukraine can affect to tell the in the international Association Agreement truth arena prospects 12 14 16 neighbours economics Time to Shove Off Greek Consequences War and Myth The Soviet Union Ratification of the The real roots of was undermined by Association Agreement Ukraine’s energy stagnation and a sense of and FTA will depend dependence go back hopelessness. Is the same on whether political to the oligarchs thing happening again? repression stops 18 22 24 investigation society You’d Rather Be Dead Tour de Ukraine Who Is Scared While pharmaceutical Ukrainians switch of Ukrainian Hackers? groups fight for the to bicycles, pushing Ukrainian market, Ukraine’s supply local authorities to cybercriminals -

Ukraine's Domestic Affairs

No. 1 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JANUARY 7, 2001 7 2000: THE YEAR IN REVIEW on February 22, aimed to “increase the economic inde- cent of farmers leased land, according to the study, while Ukraine’s domestic affairs: pendence of the citizenry and to promote entrepreneurial another 51 percent were planning to do so. activity,” said Minister of the Economy Tyhypko. The survey produced by the IFC came at the conclu- Mr. Tyhypko, who left the government a few weeks sion of a $40 million, five-year agricultural and land the good, the bad, the ugly later over disagreements with Ms. Tymoshenko and was reform project. elected to a vacant Parliament seat in June, indicated that n the domestic front in 2000 it was a roller coast- Trouble in the energy sector the program would assure deficit-free budgets, and even er ride for Ukraine, the economy being one of the budget surpluses for Ukraine, which could lead to repay- few surprisingly steady elements in an otherwise Reform of Ukraine’s most troubled economic sector, ment of wage and debt arrears, a radical reduction in the unstable year. fuel and energy, proceeded much more turbulently and country’s debt load and a stable currency. A stated longer- The new millennium began at a high point for Ukraine. claimed at least two victims. Ms. Tymoshenko, the con- O term goal was the privatization of land and resurgence of At the end of 1999 the nation had re-elected a president troversial energy vice prime minister, was not, however, the agricultural sector. -

Human Rights in Ukraine – 2005

HUMAN RIGHTS IN UKRAINE – 2005 HUMAN RIGHTS ORGANIZATIONS REPORT UKRAINIAN HELSINKI HUMAN RIGHTS UNION KHARKIV HUMAN RIGHTS PROTECTION GROUP KHARKIV «PRAVA LUDYNY» 2006 1 BBK 67.9(4) H68 In preparing the cover, the work of Alex Savransky «Freedom is on the march» was used Designer Boris Zakharov Editors Yevgeny Zakharov, Irina Rapp, Volodymyr Yavorsky Translator Halya Coynash The book is published with the assistance of the International Renaissance Foundation and the Democracy Fund of the U.S. Embassy, Kyiv The views of the authors do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Government Human Rights in Ukraine – 2005. Report by Human Rights Organizations. / Editors H68 Y.Zakharov, I.Rapp, V.Yavorsky / Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union, Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group – Kharkiv: Prava Ludyny, 2006. – 328 p. ISBN 966-8919-08-4. This book considers the human rights situation in Ukraine during 2005 and is based on studies by various non-governmental human rights organizations and specialists in this area. The first part gives a general assessment of state policy with regard to human rights in 2005, while in the second part each unit concentrates on identifying and analysing violations of specific rights in 2005, as well as discussing any positive moves which were made in protecting the given rights. Current legislation which encour- ages infringements of rights and freedoms is also analyzed, together with draft laws which could change the situation. The conclusions of the research contain recommendations for eliminating -

Abuse of Power – Corruption in the Office of the President Is His Most Recent Book

Contents 1. Preface 2. 1 “Evil has to be stopped” 3. 2 Marchuk, the arch-conspirator 4. 3 Kuchma fixes his re-election 5. 4 East & West celebrate Kuchma’s victory 6. 5 Kuchma and Putin share secrets 7. 6 Corruption 8. 7 Haunted by Lazarenko 9. 8 Bakai “the conman” 10. 9 “Yuliya must be destroyed” 11. 10 Prime minister’s wife “from the CIA”? 12. 11 Kidnapping Podolsky & killing Gongadze 13. 12 Covering up murder 14. 13 Marchuk’s “secret coordinating center” 15. 14 Kolchuga fails to oust Kuchma 16. 15 The Melnychenko-Kuchma pact 17. 16 “We can put anyone against the wall” 18. 17 Fixed election sparks Orange Revolution 19. 18 Yanukovych’s revenge 20. Bibliography 21. Acknowledgements 22. A note on the author 23. Books by JV Koshiw Artemia Press Ltd Published by Artemia Press Ltd, 2013 www.artemiabooks.com ISBN 978-0-9543764-3-7 Copyright © JV Koshiw, 2013 All rights reserved. Database right Artemia Press Ltd (maker) The photograph on the front cover It shows President Leonid Kuchma and Viktor Yushchenko clasping hands, while his rival Viktor Yanukovych looks on. Yushchenko’s pot marked face bears witness to the Dioxin poisoning inflicted on him a few weeks earlier during the 2004 presidential election campaign. Photo taken by Valeri Soloviov on Nov. 26, 2004, during the negotiations to end the Orange Revolution (Photo UNIAN). System of transliterations The study uses the Library of Congress system of transliteration for Ukrainian, with exceptions in order to make Ukrainian words easier to read in English. The letter є will be transcribed as ye and not ie. -

Erica Griedergrieder

20160425_cover61404-postal.qxd 4/5/2016 8:49 PM Page 1 April 25, 2016 $4.99 CLAIRE BERLINSKI: KEVIN D. WILLIAMSON: VICTOR DAVIS HANSON: Belgium, Cradle of Terror The Lemonade Menace Art and the Free Man GETTINGGETTING CRUZ He’s an underestimated but shrewd and RIGHT effective candidate EricaErica GriederGrieder www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 4/4/2016 1:51 PM Page 1 TOC--READY_QXP-1127940144.qxp 4/6/2016 2:09 PM Page 1 Contents APRIL 25, 2016 | VOLUME LXVIII, NO. 7 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 26 The Underestimated Mr. Cruz Douglas Murray on euthanasia If not for Ted Cruz, Donald Trump would p. 32 inevitably be the 2016 presidential nominee. Yet he’s a weak front-runner, having lost about a dozen contests to Cruz prior to the BOOKS, ARTS Wisconsin primary. The GOP is finally, at & MANNERS long last, taking its Trump problem 36 LEVIATHAN RISING seriously, and its ability to thwart his bid Mario Loyola reviews Liberty’s Nemesis: The Unchecked for the nomination is wholly contingent Expansion of the State, edited by Dean Reuter and John Yoo. on Cruz ’s ongoing success. Erica Grieder 38 ART AND THE FREE MAN COVER: THOMAS REIS Victor Davis Hanson reviews David’s Sling: A History of ARTICLES Democracy in Ten Works of Art, by Victoria C. Gardner Coates. THEIR GEORGE WALLACE—AND OURS by Richard Lowry 16 42 THE STRAIGHT DOPE Donald Trump channels the lurid voice of American populism. Fred Schwarz reviews The War on TRUMP’S COUNTERFEIT MASCULINITY by David French Alcohol: Prohibition and the 19 Rise of the American State, It reinforces every feminist stereotype. -

Serhiy KUDELIA

Serhiy KUDELIA Department of Political Science Baylor University One Bear Place #97276 Waco, TX 76798 Phone: 254-710-6050 [email protected] CURRENT POSITION Assistant Professor of Political Science, Baylor University (from August, 2012) RESEARCH IN TERESTS Political Regimes and Institutional Design; Political Violence and Civil Wars; Social Movements and Revolutions; Post-communism. EDUCATION Johns Hopkins University, Paul Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) — PhD, International Relations (2008) Stanford University – MA, Political Science (1999) Ivan Franko Lviv National University (Ukraine) – BA, International Relations (1998) TEACHING EXPERIENCE August, 2012 – present Assistant Professor of Political Science, Baylor University August 6 – 24, 2011: Ukrainian Studies Summer School, Ernst Moritz Arndt University of Greifswald (Germany) January 2009 – August 2011 Assistant Professor of Political Science, National University “Kyiv-Mohyla Academy” (Ukraine) September 2007- May 2008/September – December, 2011 Professorial Lecturer, Johns Hopkins University (SAIS) RESEARCH EXPERIENCE September 2011 – May 2012: Petrach Visiting Scholar, Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies (IERES), George Washington University. September 2009 – June 2010: Jacyk Post-doctoral Fellow, Center for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies (CERES), University of Toronto. 2 June 1999 – September 2000: Research Assistant, Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, Stanford University. GOVERNME NT/POLICY EXPERIENCE Advisor to Deputy Prime Minister of Ukraine — May 2008 - April 2009 Prepared analytical reports and policy memos, drafted policy statements and held interagency negotiations on the issues of Ukraine’s infrastructural development in the run-up to UEFA EURO-2012. ACADEMIC PUBLICATION S AND PAPERS BOOKS The Strategy of Campaigning: Lessons from Ronald Reagan and Boris Yeltsin, with Kiron Skinner, Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Condoleezza Rice (Ann Arbor, MI:University of Michigan Press, 2007). -

President of China Enlists Ukraine's Support During Visit to Kyiv U.S. National Security Adviser Presses Reform in Ukraine

INSIDE:• Paris Declaration seeks more transparency in OSCE — page 3. • Heorhii Gongadze awarded international journalism prize — page 4. • Lviv scholar notes continuing Russification in Ukraine — page 12. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXIX HE KRAINIANNo. 30 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JULY 29, 2001 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine President of China enlists Ukraine’s support during visit to Kyiv U.S. Tnational securityU adviser W by Maryna Makhnonos presses reform in Ukraine Special to The Ukrainian Weekly by Maryna Makhnonos KYIV – President Jiang Zemin of China enlisted Special to The Ukrainian Weekly Ukraine’s support for his country’s opposition to U.S. missile defense plans and preservation of the ABM KYIV – Ukraine’s integration into European society treaty, signing a joint Chinese-Ukrainian declaration of depends upon political and economic reforms, as well as friendship and comprehensive cooperation on July 21. transparent investigations of journalists’ killings, U.S. “This treaty is the foundation of the structure of inter- National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice said on July 25 during her visit to Ukraine’s capital. national agreements on limiting and reducing strategic “A very strong message is sent about political reform, offensive weapons,” the declaration said. about free press, judiciary reform and transparency in the “Ukraine and China believe that global strategic sta- [murder] cases that are of worldwide attention here,” Dr. bility and international safety depend upon the 1972 Rice said during a meeting with representatives of leading Anti-Ballistic Missile treaty,” it said. Ukrainian media outlets and non-governmental organiza- Mr. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 2005, No.40

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE:• Verkhovna Rada commission reports on the Gongadze case — page 2. •A Ukrainian American journalist’s book about Chornobyl — page 5. • Volodymyr Klitschko’s latest victory makes him a contender — page 19. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXIII HE KRAINIANNo. 40 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2005 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine AsT fifth anniversaryU passes, President announcesW appointees Gongadze case still not over to hisby Zenon new Zawada team inM governmentr. Stashevskyi and Mr. Yekhanurov are Kyiv Press Bureau like-minded thinkers, Mr. Stoyakin said. Appearing to fulfill his commitment to KYIV – President Viktor Yushchenko remove wealthy businessmen with con- formed most of his new government by flicts of interest, Mr. Yushchenko September 28, selecting a team he relieved trucking magnate Yevhen expects will work pragmatically and Chervonenko from the post of transporta- without the vicious in-fighting their pred- tion minister and David Zhvania from the ecessors engaged in. emergency situations minister post. To serve that cause, Mr. Yushchenko Yet, Mr. Yushchenko tapped another mostly chose appointees that belong to businessman, Viktor Baloha of the Our his Our Ukraine People’s Union party or Ukraine faction, to replace Mr. Zhvania. its allies. Mr. Baloha is a partner in a family busi- Of 24 Cabinet positions, Mr. ness, Barva, which engages in wholesale Yushchenko has replaced eight. Another trade of food products. He served as oblast 12 ministers will remain; among them administration chair for the Zakarpattia are two switching their job titles. Oblast. In his Who’s Who in Ukraine sub- Mr. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 2005, No.46

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE:• Ottawa Chair of Ukrainian Studies receives major donation — page 4. • Ukraine’s U.N. envoy speaks on Holocaust, Holodomor — page 6. • Lviv plays host to first annual Viennese ball — page 15. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXIII HE No.KRAINIAN 46 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 2005 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine New Tprocurator inherits Uunresolved high-profile cases Latest pollsW show Yushchenko bloc slipping to third in public support by Zenon Zawada part ways with Ms. Tymoshenko, their Kyiv Press Bureau united Our Ukraine bloc was the domi- nant political force in Ukrainian politics. KYIV – President Viktor Yushchenko’s What has emerged in Ukraine’s cur- split with former Orange Revolution ally rent political landscape is that three par- Yulia Tymoshenko has not only plundered ties each dominate a region, said his party’s potential but may also pave the Volodymyr Polokhalo, the center’s aca- way for Viktor Yanukovych to become demic director and editor of the website Ukraine’s next prime minister, according Politychna Dumka, formerly a magazine. to a poll released on October 31. The Party of Regions still enjoys Of 2,400 Ukrainians surveyed in late immense popularity in the eastern and October, 20.7 percent would vote for the southern oblasts, the Yulia Tymoshenko Party of the Regions and 17.7 percent Bloc has emerged as the favorite in would vote for the Yulia Tymoshenko Ukraine’s central oblasts, and the Our Bloc, according to a poll conducted by Ukraine People’s Union party commands Kyiv’s Socio-Vymir Center for western Ukraine. -

Ukraine's Security Forces: Bloated, Incompetent and Still Neo-Soviet Taras Kuzio

Eurasia Daily Monitor -- Volume 10, Issue 22 Ukraine’s Security Forces: Bloated, Incompetent and Still Neo-Soviet Taras Kuzio More than 20 years after independence, Ukraine’s security forces are over-manned, incompetent and largely remain neo-Soviet in their operating culture. On January 18, the prosecutor’s office accused former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko of being in league with Pavlo Lazarenko (prime minister in 1996–1997) for the murder of Donetsk oligarch Yevhen Shcherban. Allegedly, she paid $2.329 million from her accounts, while Lazarenko paid another half a million dollars in cash for the murder (http://www.gp.gov.ua/ua/news.html?_m=publications&_t=rec&id=115177&fp=40). When asked why the prosecutor’s office had not initiated these criminal charges when he was in power, former Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma replied, “The Prosecutor-General [Mykhaylo] Potebenko, in his reports, said at the time there were no grounds for legal action [against Tymoshenko]. And that is it.” “And against Lazarenko, at that time, there were [grounds for opening a case],” Kuchma added (http://www.pravda.com.ua/news/2013/01/24/6982168/). Interviewed on Russian television, Kuchma remains adamant that Tymoshenko had nothing to do with the murder of Shcherban (http://www.pravda.com.ua/news/2013/02/3/6982753/). Under Presidents Kuchma and Viktor Yushchenko, Ukraine’s moribund security forces and prosecutor’s office were unable to find evidence linking Tymoshenko to the Shcherban murder. The new “information” against Tymoshenko is part of a concerted campaign to remove her forever from Ukrainian politics and “prove” to the West her case is allegedly not political.