Protestant Worship Music Charles L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to Resources for SINGING and PRAYING the PSALMS

READ PRAY SING A Guide to Resources for SINGING and PRAYING the PSALMS – WELCOME – Voices of the Past on the Psalter We are delighted you have come to this conference, and I pray it has been helpful to you. Part of our aim is that you be encouraged and helped to make use of the Psalms in your own worship, using them as a guide for prayer and Dietrich Bonhoeffer singing. To that end we have prepared this booklet with some suggested “Whenever the Psalter is abandoned, an incomparable treasure vanishes from resources and an explanation of metrical psalms. the Christian church. With its recovery will come unsuspected power.” Special thanks are due to Michael Garrett who put this booklet together. We Charles Spurgeon have incorporated some material previously prepared by James Grant as well. “Time was when the Psalms were not only rehearsed in all the churches from day to day, but they were so universally sung that the common people As God has seen fit to give us a book of prayers and songs, and since he has knew them, even if they did not know the letters in which they were written. so richly blessed its use in the past, surely we do well to make every use of it Time was when bishops would ordain no man to the ministry unless he knew today. May your knowledge of God, your daily experience of him be deeply “David” from end to end, and could repeat each psalm correctly; even Councils enhanced as you use his words to teach you to speak to him. -

Service Music

Service Music 386 387 388 389 390 391 392 393 394 395 396 397 398 399 400 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 412 413 414 415 416 417 418 419 420 421 422 423 424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432 433 434 435 436 437 Indexes Copyright Permissions Copyright Page Under Construction 441 442 Chronological Index of Hymn Tunes Plainsong Hymnody 1543 The Law of God Is Good and Wise, p. 375 800 Come, Holy Ghost, Our Souls Inspire 1560 That Easter Day with Joy Was Bright, p. 271 plainsong, p. 276 1574 In God, My Faithful God, p. 355 1200?Jesus, Thou Joy of Loving Hearts 1577 Lord, Thee I Love with All My Heart, p. 362 Sarum plainsong, p. 211 1599 How Lovely Shines the Morning Star, p. 220 1250 O Come, O Come Emmanuel 1599 Wake, Awake, for Night Is Flying, p. 228 13th century plainsong, p. 227 1300?Of the Father's Love Begotten Calvin's Psalter 12th to 15th century tropes, p. 246 1542 O Food of Men Wayfaring, p. 213 1551 Comfort, Comfort Ye My People, p. 226 Late Middle Ages and Renaissance Melodies 1551 O Gladsome Light, p. 379 English 1551 Father, We Thank Thee Who Hast Planted, p. 206 1415 O Love, How Deep, How Broad, How High! English carol, p. 317 Bohemian Brethren 1415 O Wondrous Type! O Vision Fair! 1566 Sing Praise to God, Who Reigns Above, p. 324 English carol, p. 320 German Unofficial English Psalters and Hymnbooks, 1560-1637 1100 We Now Implore the Holy Ghost 1567 Lord, Teach Us How to Pray Aright -Thomas Tallis German Leise, p. -

1494:1 Russellville, Arkansas

10-11 z A HISTORICAL SURVEY OF PSALM SETTINGS FROM THE TIME OF THE REFORMATION THROUGH STRAVINSKY'S "SYMPHONIE DES PSAUMES" THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State Teachers College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Virginia Sue Williamson, B. M. 1494:1 Russellville, Arkansas August, 1947 14948i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.. .... .......... v Chapter I. INTRODUCTION ...... ....... ... 1 II. LATIN PSALM SETTINGS..... ....... 6 III. THE REFORMATION AND CHURCH MUSIC . 13 IV. EARLYPSALTERS . 25 The Genevan Psalter English Psalters C e Psalter Sternhold and-Hopkins Psalter D Psalter Este Psalter Allison's Psalter Ainsworth Psalter Ravencroft's Psalter John Keble Psalter Cleveland Psalter The Bay Psalm Book V. SCHUTZ TO STRAVINSKY. ........... 51 Heinrich Schutz (1585-1682) Henry Purcell (1658 or 1659-1695) George Frederic Handel (1685-1759) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Franz Peter Schubert (1797-1828) Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809-1847) Franz Liszt (1811-1886) Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Cesar Franck (1822-1890) Charles Camille Saint-Saens (1835-1921) Mikail M. Ippolotov-Ivanov (1859----- Charles Martin Loeffler (1861-----) iii Chapter Page Albert Roussel (1869- ---- ) Igor Stravinsky (1882 .---- ) VI. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION . 86 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 89 iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. "L'Amour de moy" (Ps. 130), from the Psalter d'Anvers of 1541 . 32 2. Secular melody used by Bourgeois for Psalm 25 . 32 3. "Susato," used for Psalms 65 and 72 in Genevan Psalter .*.*.*. .*.9** .* . ,933 4. "Paris et Gevaet," used for Psalm 134 in the Genevan Psalter of 1551 . -

Concordia Journal

CONCORDIA JOURNAL Volume 28 July 2002 Number 3 CONTENTS ARTICLES The 1676 Engraving for Heinrich Schütz’s Becker Psalter: A Theological Perspective on Liturgical Song, Not a Picture of Courtly Performers James L. Brauer ......................................................................... 234 Luther on Call and Ordination: A Look at Luther and the Ministry Markus Wriedt ...................................................................... 254 Bridging the Gap: Sharing the Gospel with Muslims Scott Yakimow ....................................................................... 270 SHORT STUDIES Just Where Was Jonah Going?: The Location of Tarshish in the Old Testament Reed Lessing .......................................................................... 291 The Gospel of the Kingdom of God Paul R. Raabe ......................................................................... 294 HOMILETICAL HELPS ..................................................................... 297 BOOK REVIEWS ............................................................................... 326 BOOKS RECEIVED ........................................................................... 352 CONCORDIA JOURNAL/JULY 2002 233 Articles The 1676 Engraving for Heinrich Schütz’s Becker Psalter: A Theological Perspective on Liturgical Song, Not a Picture of Courtly Performers James L. Brauer The engraving at the front of Christoph Bernhard’s Geistreiches Gesang- Buch, 1676,1 (see PLATE 1) is often reproduced as an example of musical PLATE 1 in miniature 1Geistreiches | Gesang-Buch/ -

Introduction to the Genevan Psalter

Introduction to the Genevan Psalter David T. Koyzis, Redeemer University College, Ancaster, Ontario, Canada The chief liturgical book of God’s people For millennia the biblical psalter has been the chief liturgical book of God’s people of the old and new covenants. The Psalms are unique in that they simultaneously reflect the full range of human experience and reveal to us God’s word. In them we hear expressions of joy and lament, cries for revenge against enemies, confession of sin, acknowledgement of utter dependence on God, recitations of his mighty acts in history, and finally songs of praise and adoration. With the rest of the Old Testament, Christians share the biblical Psalter with the Jewish people, with whom it originates. Many of the Psalms are ascribed to David himself, and there is even a tradition making him the author of the entirety of the book. While there is no certainty to the ascriptions traditionally prefacing each psalm, it is likely that many of them do indeed originate with the revered founder of the Judaic dynasty. If the latest of the psalms were composed during the Persian and perhaps even into the Hasmonean eras, then the Psalter was compiled over the better part of a millennium of Jewish history before being finalized sometime during the second temple period. Translated into Greek as part of the Septuagint, the Psalms naturally found their way into early Christian usage as well. The New Testament writers see in several of the Psalms, for example Psalms 2, 8, 22, 41, 69, 110 and 118, a foretaste of the coming Messiah. -

18Summer-Vol24-No3-TM.Pdf

Theology Matters Vol 24, No. 3 Summer 2018 Rediscovering the Office of Elder The Shepherd Model by Eric Laverentz At the center of our name, tradition, identity, and ethos guard the purity of the church in the lives of its as Presbyterians is a term that has lost almost all members. In dealing with offenses, the session holds connection with what it meant to most who have called both judiciary and executive authority. But the most themselves Presbyterians over the last five centuries. important function of elders is to watch over the flock, Even to many of our parents and grandparents being a of which they are under-shepherds, guarding, “presbyter” or “elder” meant something quite different counseling, comforting, instructing, encouraging, and than it means to most of us today. admonishing, as circumstances require. The penalties imposed on wrongdoers are censure, suspension from The not too distant past paints a picture of elders vested the communion of the Church, and excommunication.1 with spiritual authority who were deeply enmeshed in the lives of people. This is very different from the As foreign as this description of duties sounds to 21st service rendered in most elder-led churches today. We century ears, it was not the elders of First Presbyterian have seen a total shift in understanding of what it Church, Dayton, Ohio, in the 1880s who were guarding means to be an elder over the last generation or two. the purity of their members and exercising discipline The shift is so complete that few of us have any that were out of touch with the historical and Biblical institutional memory of the way it used to be. -

Psalm 100 Sweelinck, Ed

CM9412 Psalm 100 Sweelinck, ed. Hooper / SAATB a cappella Psalm 100 Vous tous qui la terr’ habitez Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck For RANDALL HOOPER unlawfulpromotional SAATB Voices a cappella Duration: 3:49 to RANGES: copy use or only print FREE MP3 rehearsal and accompaniments www.carlfischer.com 2 About the Composer Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562-1621) was born and raised in Amsterdam. He worked as the organist at the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam from ca. 1580 until his death in 1621. Because the Calvinists saw the organ as a worldly instrument and forbade its use during religious services, he was actually a civil servant employed by the city of Amsterdam. It is assumed that his duties were to provide music twice daily in the church, an hour in the morning and in the evening. When there was a service, this hour came before and/or after the service. As well as being one of the most famous organists and teachers of this time, Sweelinck was the last and most important com- poser of the musically rich golden era of the Netherlanders. All of his vocal works Forwere printed in his lifetime. His polyphonic setting of Psalter has been called a monu- ment of Netherlandish music, unequalled in the sphere of sacred polyphony. From the outset he intended to set the entire Psalter, and he dedicated much of his creative life unlawfulto this music.promotional The texts are from the French metrical Psalter, not the Dutch version which was used in most Dutch churches. This is probably because the psalms were not intended for use in public Calvinist services but rather within a circle of well-to-do musical amateurs among whom French was the preferred language. -

Christianity and Oral Culture in Anglo-Saxon Verse

Oral Tradition, 24/2 (2009): 293-318 The Word Made Flesh: Christianity and Oral Culture in Anglo-Saxon Verse Andy Orchard As far as the history of English literature goes, in the beginning was Cædmon’s Hymn, and Cædmon’s Hymn, at least as an inaugural event, seems something of a damp squib.1 Not just because Bede’s description of the unexpected inspiration of the apparently Celtic-named putative parent of English verse has so many analogues in the form of similar and sometimes seemingly more miraculous stories (see, for examples, Atherton 2002; Ireland 1987; Lester 1974; O’Donnell 2005:29-60 and 191-202), including a Latin autobiographical account of the “inspiration” of the drunk Symphosius (whose Greek-derived name means “drinking-party animal” or suchlike), supposedly similarly spurred to song at a much earlier North African booze-up of his own, the narrative of which seems to have been known in Anglo-Saxon England at around the same time Cædmon took his fateful walk to commune with the common herd (Orchard forthcoming a). And not just because for many readers there is a lingering sense of disappointment on first acquaintance, since however well-constructed we are increasingly told that Cædmon’s Hymn may be (Howlett 1974; Conway 1995; but see O’Donnell 2005:179-86), the fact that the repetition of eight so seemingly trite and formulaic epithets for God (seven of them different, however) has seemed to some a tad excessive in a poem of only nine lines (Fry 1974 and 1981; Stanley 1995). Still further factors seem to undermine the iconic status of Cædmon’s Hymn, including its variant forms and the rumbling (if unlikely) suggestions that it is no more than a back-translation from Bede’s somehow superior Latin, at the margins of which it so often appears in the manuscripts (Kiernan 1990; Isaac 1997). -

The Scottish Metrical Psalter of 1635� 69

The Scottish Metrical Psalter of 1635 69 The Scottish Metrical Psalter of 1635. THERE is undoubtedly arising at this time a very great interest in the music of our Scottish Psalters, and the particular edition that is receiving most attention is that of 1635. The Scottish Metrical Psalter was first published in 1564, and was, in all its editions, bound up with the Book of Common Order. It was the duly authorised Psalter until it was superseded in 1650 by the Psalter still used in our churches to-day, and of which a new edition, com- panion to the Revised Hymnary, is to be published this year. The popularity of the Reformation Psalters may be judged by the fact that at least twenty-five editions, but more probably thirty, were published between the years 1564 and 1644—that is, one edition practically every three years. The exact number of editions cannot be stated owing to the difficulty of deciding whether certain editions are new or merely reissues in later years. Now, why should the edition of 1635 be more worthy of attention than all these others ? Our forefathers, in their wisdom, never published the Psalter without the tunes, the first verse of each Psalm appearing directly under the notes of the music. In every edition previous to that of 1635 the Psalters contained the melody only. As the title-page tells us, the famous 1635 edition was published " with their whole tunes in foure or mo parts." It was thus the first harmonised edition, and so of greater interest from the musical point of view. -

Cantus Christi Copyright © 2002 Christ Church, Moscow, Idaho 2004 Revised Edition

Cantus Christi Copyright © 2002 Christ Church, Moscow, Idaho 2004 Revised Edition Published by Canon Press P.O. Box 8729, Moscow, ID 83843. 800–488–2034 www.canonpress.org 05 06 07 08 09 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the author, except as provided by USA copyright law. The publisher gratefully acknowledges permission to reprint texts, tunes and arrangements granted by the publishers, organizations and individuals listed on pages xviii and 443–445. Every effort has been made to secure current copyright permission information on the Psalms, hymns, and service music used. If any right has been infringed, the publisher promises to make the correction in subsequent printings as the additional information is received. ISBN: Cantus Christi (clothbound) 1–59128–003- 6 ISBN: Cantus Christi (accompanist’s edition) 1–59128–004–4 Tabl e of Conte nt s Manifesto on Psalms and Hymns by Douglas Wilson . v Introduction to Musical Style by Dr. Louis Schuler . ix List of Abbreviations . xvii Copyright Holders . xviii Section I Psalms . 1 Section II Hymns . 197 Baptism . 198 Communion . 202 Advent . 218 Christmas . 230 Epiphany . 251 Christ’s Passion . 255 Triumphal Entry . 268 Resurrection . 269 Ascension . 274 Pentecost . 276 All Saints . 280 Thanksgiving . 283 Adoration . 286 Supplication . 336 Evening Hymns . 377 Section III Service Music . 385 Indexes . 441 Copyright Permissions . 443 Chronological Index of Hymn Tunes . 446 Index of Authors, Composers, and Sources . -

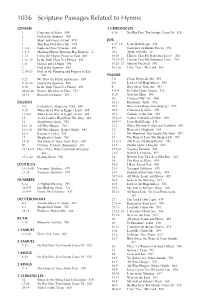

1036 Scripture Passages Related to Hymns

1036 Scripture Passages Related to Hymns GENESIS 2 CHRONICLES 1: Cantemos al Señor 695 6:14 No Hay Dios Tan Grande Como Tú 525 1: God of the Sparrow 485 1: Many and Great, O God 479 JOB 1: This Day God Gives Me 693 3:17–18 Jesus Shall Reign 478 1:1–2 Soplo del Dios Viviente 458 8:9 Cantemos un Himno Nuevo 431 1:3–5 Morning Hymn (Morning Has Broken) 4 14:1 Abide with Me 21 1:12 I Sing the Mighty Power of God 481 19:25 I Know That My Redeemer Lives! 434 1:12–13 In the Bulb There Is a Flower 491 19:25–27 I Know That My Redeemer Lives 795 1:31 Gracias por el Amor 696 19:25–27 Song of Farewell 796 2: God of the Sparrow 485 42:1–6 I Say “Yes,” My Lord 565 2:18–23 God, in the Planning and Purpose of Life 793 PSALMS 8:22 We Plow the Fields and Scatter 659 3:4 Christ Be beside Me 553 9:12–16 God of the Sparrow 485 4:8 Lord of All Hopefulness 556 9:15 In the Bulb There Is a Flower 491 8: How Great Thou Art 483 28:10–22 Nearer, My God, to Thee 794 8:4–5 El Cielo Canta Alegría 516 28:12 Blessed Assurance 582 9:10 You Are Mine 596 16: Center of My Life 566 EXODUS 16:11 Enséñame, Señor 561 3:5 Cantando la Alegría de Vivir 680 18:3 How Can I Keep from Singing? 570 6:10 When Israel Was in Egypt’s Land 488 19:2 Cantemos al Señor 695 11:4–8 When Israel Was in Egypt’s Land 488 19:2 Canticle of the Sun 482 15: At the Lamb’s High Feast We Sing 449 19:2–4 Vamos Cantando al Señor 689 16: Shepherd of Souls 755 19:5–7 Jesus Shall Reign 478 16:1–21 All Who Hunger 769 22:2 When My Soul Is Sore and Troubled 559 16:1–21 All Who Hunger, Gather Gladly 684 23: Heart -

John Calvin and the Psalmody of the Reformed Churches

John Calvin and the Psalmody of the Reformed Churches Author(s): Benson, Louis Fitzgerald Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: By the turn of the 20th century, Benson had become a leading authority in Reformed hymnology. His personal library, in fact, eventually contained over 9,000 volumes. In 1907, Benson delivered Princeton Theological Seminary's L.P. Stone Lectures, and his series of talks concerned the topic of congregational singing in the Calvinist tradition. Most of the lectures concern the development of church music in Geneva during John Calvin's lifetime. Kathleen O©Bannon CCEL Staff i Contents John Calvin and the Psalmody of the Reformed Churches 1 I. The Historical Background. 2 II. The Situation at Geneva and Calvin’s Proposals. 7 III. Inauguration Of The Calvinistic Psalmody At Strassburg. 11 IV. Clement Marot And The Court Psalmody. 14 V. Inauguration Of Psalmody At Geneva. 19 VI. The Genevan Psalter: Calvin, Marot And Beza. 21 VII. The Melodies of the Genevan Psalter. 25 VIII. Spread of the Genevan Psalmody in France. 30 IX. The Psalmody of the Reformed Churches of France. 33 X. Calvin: His Relations to Metrical Psalmody and Church Music. 36 XI. Appendix: The Decline Of Psalmody In French-Speaking Reformed Churches. 45 Appendix to this Electronic Text: Provenance 54 Indexes 58 Index of Pages of the Print Edition 59 ii This PDF file is from the Christian Classics Ethereal Library, www.ccel.org. The mission of the CCEL is to make classic Christian books available to the world. • This book is available in PDF, HTML, ePub, Kindle, and other formats.