Crossing the Shadow Lines: Essays on the Topicality of Amitav Ghosh's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Patra Bharati 2003; 48P

1. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Patra Bharati 2003; 48p. Rs.30 It Is the famous rhymes collection of Bengali Literature. 2. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: National Book Agency 2003; 60p. Rs.30 It in the most popular Bengala Rhymes ener written. 3. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Dey's 1990; 48p. Rs.10 It is the most famous rhyme collection of Bengali Literature. 4. Aachin Paakhi Dutta, Asit : Nikhil Bharat Shishu Sahitya 2002; 48p. Rs.30 Eight-stories, all bordering on humour by a popular writer. 5. Aadhikar ke kake dei Mukhophaya, Sutapa Kolkata: A 'N' E Publishers 1999; 28p. Rs.16 8185136637 This book intend to inform readers on their Rights and how to get it. 6. Aagun - Pakhir Rahasya Gangopadhyay, Sunil Kolkata: Ananda Publishers 1996; 119p. Rs.30 8172153198 It is one of the most famous detective story and compilation of other fun stories. 7. Aajgubi Galpo Bardhan, Adrish (ed.) : Orient Longman 1989; 117p. Rs.12 861319699 A volume on interesting and detective stories of Adrish Bardhan. 8. Aamar banabas Chakraborty, Amrendra : Swarnakhar Prakashani 1993; 24p. Rs.12 It is nice poetry for childrens written by Amarendra Chakraborty. 9. Aamar boi Mitra, Premendra : Orient Longman 1988; 40p. Rs.6 861318080 Amar Boi is a famous Primer-cum-beginners book written by Premendra Mitra. 10. Aat Rahasya Phukan, Bandita New Delhi: Fantastic ; 168p. Rs.27 This is a collection of eight humour A Mystery Stories. 12. Aatbhuture Mitra, Khagendranath Kolkata: Ashok Prakashan 1996; 140p. Rs.25 A collection of defective stories pull of wonder & surprise. 13. Abak Jalpan lakshmaner shaktishel jhalapala Ray, Kumar Kolkata: National Book Agency 2003; 58p. -

Appellate Jurisdiction

Appellate Jurisdiction Daily Supplementary List Of Cases For Hearing On Monday, 26th of April, 2021 CONTENT SL COURT PAGE BENCHES TIME NO. ROOM NO. NO. HONBLE CHIEF JUSTICE THOTTATHIL B. 1 On 26-04-2021 1 RADHAKRISHNAN 1 DB -I At 11:15 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJESH BINDAL 16 On 26-04-2021 2 3 HON'BLE JUSTICE ANIRUDDHA ROY DB - II At 11:15 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 37 On 26-04-2021 3 6 HON'BLE JUSTICE MD. NIZAMUDDIN DB - III At 11:15 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 3 On 26-04-2021 4 7 HON'BLE JUSTICE MD. NIZAMUDDIN DB - III At 11:15 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON 2 On 26-04-2021 5 9 HON'BLE JUSTICE KAUSIK CHANDA DB- IV At 11:15 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 17 On 26-04-2021 6 26 HON'BLE JUSTICE SAUGATA BHATTACHARYYA DB-V At 11:15 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 11 On 26-04-2021 7 33 HON'BLE JUSTICE ABHIJIT GANGOPADHYAY DB At 11:15 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 11 2 -04-2021 8 For 7 37 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBHASIS DASGUPTA DB At 12:55 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 28 On 26-04-2021 9 38 HON'BLE JUSTICE TIRTHANKAR GHOSH DB - VII At 11:15 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SHIVAKANT PRASAD 9 On 26-04-2021 10 58 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBHASIS DASGUPTA DB At 02:00 PM 9 On 26-04-2021 11 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHIVAKANT PRASAD 59 SB - II At 11:15 AM 13 On 26-04-2021 12 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJASEKHAR MANTHA 64 SB - III At 11:15 AM 8 On 26-04-2021 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE SABYASACHI BHATTACHARYYA 84 SB - IV At 11:15 AM 26 On 26-04-2021 14 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHEKHAR B. -

Appellate Jurisdiction

Appellate Jurisdiction Daily Supplementary List Of Cases For Hearing On Tuesday, 27th of July, 2021 CONTENT SL COURT PAGE BENCHES TIME NO. ROOM NO. NO. HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJESH BINDAL , CHIEF 1 On 27-07-2021 1 JUSTICE (ACTING) 1 DB-I At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJARSHI BHARADWAJ HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 3 On 27-07-2021 2 4 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM MUKHERJEE DB-II At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON 28 On 27-07-2021 3 7 HON'BLE JUSTICE BIBEK CHAUDHURI DB-III At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 16 On 27-07-2021 4 60 HON'BLE JUSTICE HIRANMAY BHATTACHARYYA DB - V At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 11 On 27-07-2021 5 68 HON'BLE JUSTICE JAY SENGUPTA DB-VI At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 30 On 27-07-2021 6 77 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBHASIS DASGUPTA DB-VII At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 4 On 27-07-2021 7 83 HON'BLE JUSTICE SAUGATA BHATTACHARYYA DB - VIII At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE 32 On 27-07-2021 8 94 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUVRA GHOSH DB - IX At 11:00 AM 8 On 27-07-2021 9 HON'BLE JUSTICE DEBANGSU BASAK 123 SB II At 11:00 AM 13 On 27-07-2021 10 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJASEKHAR MANTHA 153 SB - IV At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SABYASACHI 7 On 27-07-2021 11 189 BHATTACHARYYA SB - V At 11:00 AM 26 On 27-07-2021 12 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHEKHAR B. -

Premendra Mitra - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Premendra Mitra - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Premendra Mitra(1904 - 3 May 1988) Premendra Mitra was a renowned Bengali poet, novelist, short story writer and film director. He was also an author of Bangla science fiction and thrillers. <b>Life</b> He was born in Varanasi, India, though his ancestors lived at Rajpur, South 24 Parganas, West Bengal. His father was an employee of the Indian Railways and because of that; he had the opportunity of travelling to many places in India. He spent his childhood in Uttar Pradesh and his later life in Kolkata & Dhaka. He was a student of South Suburban School (Main) and later at the Scottish Church College in Kolkata. During his initial years, he (unsuccessfully) aspired to be a physician and studied the natural sciences. Later he started out as a school teacher. He even tried to make a career for himself as a businessman, but he was unsuccessful in that venture as well. At a time, he was working in the marketing division of a medicine producing company. After trying out the other occupations, in which he met marginal or moderate success, he rediscovered his talents for creativity in writing and eventually became a Bengali author and poet. Married to Beena Mitra, he was, by profession, a Bengali professor at City College in north Kolkata. He spent almost his entire life in a house at Kalighat, Kolkata. <b>As an Author & Editor</b> In November 1923, Mitra came from Dhaka, Bangladesh and stayed in a mess at Gobinda Ghoshal Lane, Kolkata. -

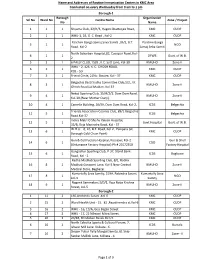

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area Conducted on every Wednesday from 9 am to 1 pm Borough-1 Borough Organization Srl No Ward No Centre Name Zone / Project No Name 1 1 1 Shyama Club, 22/H/3, Hagen Chatterjee Road, KMC CUDP 2 1 1 WHU-1, 1B, G. C. Road , Kol-2 KMC CUDP Paschim Banga Samaj Seva Samiti ,35/2, B.T. Paschim Banga 3 1 1 NGO Road, Kol-2 Samaj Seba Samiti North Subarban Hospital,82, Cossipur Road, Kol- 4 1 1 DFWB Govt. of W.B. 2 5 2 1 6 PALLY CLUB, 15/B , K.C. Sett Lane, Kol-30 KMUHO Zone-II WHU - 2, 126, K. C. GHOSH ROAD, 6 2 1 KMC CUDP KOL - 50 7 3 1 Friend Circle, 21No. Bustee, Kol - 37 KMC CUDP Belgachia Basti Sudha Committee Club,1/2, J.K. 8 3 1 KMUHO Zone-II Ghosh Road,Lal Maidan, Kol-37 Netaji Sporting Club, 15/H/2/1, Dum Dum Road, 9 4 1 KMUHO Zone-II Kol-30,(Near Mother Diary). 10 4 1 Camelia Building, 26/59, Dum Dum Road, Kol-2, ICDS Belgachia Friends Association Cosmos Club, 89/1 Belgachia 11 5 1 ICDS Belgachia Road.Kol-37 Indira Matri O Shishu Kalyan Hospital, 12 5 1 Govt.Hospital Govt. of W.B. 35/B, Raja Manindra Road, Kol - 37 W.H.U. - 6, 10, B.T. Road, Kol-2 , Paikpara (at 13 6 1 KMC CUDP Borough Cold Chain Point) Gun & Cell Factory Hospital, Kossipur, Kol-2 Gun & Shell 14 6 1 CGO (Ordanance Factory Hospital) Ph # 25572350 Factory Hospital Gangadhar Sporting Club, P-37, Stand Bank 15 6 1 ICDS Bagbazar Road, Kol - 2 Radha Madhab Sporting Club, 8/1, Radha 16 8 1 Madhab Goswami Lane, Kol-3.Near Central KMUHO Zone-II Medical Store, Bagbazar Kumartully Seva Samity, 519A, Rabindra Sarani, Kumartully Seva 17 8 1 NGO kol-3 Samity Nagarik Sammelani,3/D/1, Raja Naba Krishna 18 9 1 KMUHO Zone-II Street, kol-5 Borough-2 1 11 2 160,Arobindu Sarani ,Kol-6 KMC CUDP 2 15 2 Ward Health Unit - 15. -

Abducted Women 70–73, 87–89, 94, 105 Agamben, Giorgio 221, 246 Agomoni 148 Agunpakhi 223, 225 Agrarian Movements 16, 75–76

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-06170-5 - The Partition of Bengal: Fragile Borders and New Identities Debjani Sengupta Index More information Index Abducted women 70–73, 87–89, 94, 105 Assam 2–3, 122, 150, 160, 180, 182, 185, Agamben, Giorgio 221, 246 188–93, 196–97, 214–16, 240, 242 agomoni 148 Asom Jatiya Mahasabha 193 Agunpakhi 223, 225 Azad 199 Agrarian movements 16, 75–76, 234, Babughat 121 236–37 Bagerhat 158 Ahmed, Muzzaffar 83–84 Bandopadhyay, Ateen 19–21, 74, 93, 95, Akhyan 144, 146 102, 115 Alamer Nijer Baari 204 Bandopadhyay, Bibhutibhushan 29, 124, Ali, Agha Shahid 220 223–24 All India Congress Party 36–37, 40, 48–50, Bandopadhyay, Hiranmoy 30, 122, 149–51 73, 76, 86, 119, 125, 133, 137, 176 Bandopadhyay, Manik 17, 18, 34, 42, 44– All India Women’s Conference (AIWC) 70, 46, 48–51, 57–58, 60, 66–67, 154, 208 72, 74, 86–87, 92, 112–13, 120 Bandopadhyay, Shekhar 64, 66 Amin, Shahid 29 Bandopadhyay, Sibaji 215, 217–19 Anandamath 13, 208, 210 Bandopadhyay, Tarashankar 10–11, 17, 33, 57–58, 60–61, 63, 67, 116, 208 Anderson, Benedict 71, 220 Banerjee, Himani 187, 246 Anyo Gharey Anyo Swar 205 Banerjee, Paula 34, 248 Andul 121 Banerjee, Suresh Chandra 37 Ansars 158, 190–91 Bangla fiction 2, 60, 93, 117, 131, 165, Anti ‘Tonko’ movement 191 170, 194–95 Amrita Bazar Patrika 122, 158–60, 162, 190 Bangla literature 1, 14, 188 Ananda Bazar Patrika 181, 186 Bangla novel 11, 13, 57, 75, 146–47, 179 Aro Duti Mrityu 202, 217 Bangla partition fiction 3, 12, 18, 157, 168, Aronyak 224 226, 247 Arjun 16, 19, 142–45, 155 Bangladesh War of 1971 -

Uhm Phd 9519439 R.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality or the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106·1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521-0600 Order Number 9519439 Discourses ofcultural identity in divided Bengal Dhar, Subrata Shankar, Ph.D. University of Hawaii, 1994 U·M·I 300N. ZeebRd. AnnArbor,MI48106 DISCOURSES OF CULTURAL IDENTITY IN DIVIDED BENGAL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DECEMBER 1994 By Subrata S. -

NAAC NBU SSR 2015 Vol II

ENLIGHTENMENT TO PERFECTION SELF-STUDY REPORT for submission to the National Assessment & Accreditation Council VOLUME II Departmental Profile (Faculty Council for PG Studies in Arts, Commerce & Law) DECEMBER 2015 UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL [www.nbu.ac.in] Raja Rammohunpur, Dist. Darjeeling TABLE OF CONTENTS Page number Departments 1. Bengali 1 2. Centre for Himalayan Studies 45 3. Commerce 59 4. Lifelong Learning & Extension 82 5. Economics 89 6. English 121 7. Hindi 132 8. History 137 9. Law 164 10. Library & Information Science 182 11. Management 192 12. Mass Communication 210 13. Nepali 218 14. Philosophy 226 15. Political Science 244 16. Sociology 256 Research & Study Centres 17. Himalayan Studies (Research Unit placed under CHS) 18. Women’s Studies 266 19. Studies in Local languages & Culture 275 20. Buddhist Studies (Placed under the Department of Philosophy) 21. Nehru Studies (Placed under the Department of Political Science) 22. Development Studies (Placed under the Department of Political Science) _____________________________________________________________________University of North Bengal 1. Name of the Department : Bengali 2. Year of establishment : 1965 3. Is the Department part of a School/Faculty of the University? Department is the Faculty of the University 4. Name of the programmes offered (UG, PG, M. Phil, Ph.D., Integrated Masters; Integrated Ph.D., D.Sc., D.Litt., etc.) : (i) PG, (ii) M. Phil., (iii) Ph. D., (iv) D. Litt. 5. Interdisciplinary programmes and departments involved : NIL 6. Course in collaboration with other universities, industries, foreign institution, etc. : NIL 7. Details of programmes discontinued, if any, with reasons 2 Years M.Phil.Course (including Methadology in Syllabus) started in 2007 (Session -2007-09), it continued upto 2008 (Session - 2008-10); But it is discontinued from 2009 for UGC Instruction, 2009 regarding Ph. -

North-Western Istria the Mediterranean World of Flavour Contents

North-western Istria The Mediterranean World of Flavour Contents North-western Istria Gourmand’s Paradise 4 Gastronomic Pulse of the Region Something for Everyone 6 Food and Wine Itineraries Routes of Unforgettable Flavours 12 Istria Wine & Walk. Gastronomic manifestation. 20 Calendar of Events In the Feisty Rhythm of Tasty Food 21 Calendar of Pleasures 24 Package Tours Tailored Experiences 26 Information and Contacts 27 North-western Istria Gourmand’s Paradise Croatia Istria North-western Istria Just like a magic chest, north-western Easily accessible from a num- The heart-shaped Istria is easily reached The truffle, considered by many the king Istria abounds with untouched natural from all European cities. This largest of the world gastronomy and ascribed beauties, small architectural wonders ber of European countries, Adriatic peninsula is situated in the west- aphrodisiac characteristics and exceptional and a luxurious spectrum of colours, north-western Istria inspires ernmost part of Croatia, at the junction of culinary power, grows here. Except on the tastes and flavours. the quest for the culinary Central Europe and the Mediterranean. truffle, the Istrian cuisine also relies on home-made pasta, fish and seafood, sea- A curious visitor will find everything legacy of former generations. The north-western part of Istria welcomes sonal vegetables, home-made prosciutto required for a relaxed or active holiday, Visitors can choose from a all travellers offering them the hospital- and cheese and a variety of wild herbs. in the perfect blend of tradition and ity of the seaside towns of Umag and contemporary tourist needs. wide variety of specialities – Novigrad and picturesque inland towns of The rich variety of food is contributed from the modern Istrian sushi Buje and Brtonigla. -

Download Book

"We do not to aspire be historians, we simply profess to our readers lay before some curious reminiscences illustrating the manners and customs of the people (both Britons and Indians) during the rule of the East India Company." @h£ iooi #ld Jap €f Being Curious Reminiscences During the Rule of the East India Company From 1600 to 1858 Compiled from newspapers and other publications By W. H. CAREY QUINS BOOK COMPANY 62A, Ahiritola Street, Calcutta-5 First Published : 1882 : 1964 New Quins abridged edition Copyright Reserved Edited by AmARENDRA NaTH MOOKERJI 113^tvS4 Price - Rs. 15.00 . 25=^. DISTRIBUTORS DAS GUPTA & CO. PRIVATE LTD. 54-3, College Street, Calcutta-12. Published by Sri A. K. Dey for Quins Book Co., 62A, Ahiritola at Express Street, Calcutta-5 and Printed by Sri J. N. Dey the Printers Private Ltd., 20-A, Gour Laha Street, Calcutta-6. /n Memory of The Departed Jawans PREFACE The contents of the following pages are the result of files of old researches of sexeral years, through newspapers and hundreds of volumes of scarce works on India. Some of the authorities we have acknowledged in the progress of to we have been indebted for in- the work ; others, which to such as formation we shall here enumerate ; apologizing : — we may have unintentionally omitted Selections from the Calcutta Gazettes ; Calcutta Review ; Travels Selec- Orlich's Jacquemont's ; Mackintosh's ; Long's other Calcutta ; tions ; Calcutta Gazettes and papers Kaye's Malleson's Civil Administration ; Wheeler's Early Records ; Recreations; East India United Service Journal; Asiatic Lewis's Researches and Asiatic Journal ; Knight's Calcutta; India. -

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province. -

Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Banerjee [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Suparno, "Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3181. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. OTHER TOMORROWS: POSTCOLONIALITY, SCIENCE FICTION AND INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Suparno Banerjee B. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2000 M. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2002 August 2010 ©Copyright 2010 Suparno Banerjee All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation would not have been possible without the constant support of my professors, peers, friends and family. Both my supervisors, Dr. Pallavi Rastogi and Dr. Carl Freedman, guided the committee proficiently and helped me maintain a steady progress towards completion. Dr. Rastogi provided useful insights into the field of postcolonial studies, while Dr. Freedman shared his invaluable knowledge of science fiction. Without Dr. Robin Roberts I would not have become aware of the immensely powerful tradition of feminist science fiction.