Critical Analysis of Sustainable Development of Bukit Lagong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pulih Sepenuhnya Pada 8:00 Pagi, 21 Oktober 2020 Kumpulan 2

LAMPIRAN A SENARAI KAWASAN MENGIKUT JADUAL PELAN PEMULIHAN BEKALAN AIR DI WILAYAH PETALING, GOMBAK, KLANG/SHAH ALAM, KUALA LUMPUR, HULU SELANGOR, KUALA LANGAT DAN KUALA SELANGOR 19 OKTOBER 2020 WILAYAH : PETALING ANGGARAN PEMULIHAN KAWASAN Kumpulan 1: Kumpulan 2: Kumpulan 3: Pulih Pulih Pulih BIL. KAWASAN sepenuhnya sepenuhnya sepenuhnya pada pada pada 8:00 pagi, 8:00 pagi, 8:00 pagi, 21 Oktober 2020 22 Oktober 2020 23 Oktober 2020 1 Aman Putri U17 / 2 Aman Suria / 3 Angkasapuri / 4 Bandar Baru Sg Buloh Fasa 3 / 5 Bandar Baru Sg. Buloh Fasa 1&2 / 6 Bandar Baru Sri Petaling / 7 Bandar Kinrara / 8 Bandar Pinggiran Subang U5 / 9 Bandar Puchong Jaya / 10 Bandar Tasek Selatan / 11 Bandar Utama / 12 Bangsar South / 13 Bukit Indah Utama / 14 Bukit Jalil / 15 Bukit Jalil Resort / 16 Bukit Lagong / 17 Bukit OUG / 18 Bukit Rahman Putra / 19 Bukit Saujana / 20 Damansara Damai (PJU10/1) / 21 Damansara Idaman / 22 Damansara Lagenda / 23 Damansara Perdana (Raflessia Residency) / 24 Denai Alam / 25 Desa Bukit Indah / 26 Desa Moccis / 27 Desa Petaling / 28 Eastin Hotel / 29 Elmina / 30 Gasing Indah / 31 Glenmarie / 32 Hentian Rehat dan Rawat PLUS (R&R) / 33 Hicom Glenmarie / LAMPIRAN A SENARAI KAWASAN MENGIKUT JADUAL PELAN PEMULIHAN BEKALAN AIR DI WILAYAH PETALING, GOMBAK, KLANG/SHAH ALAM, KUALA LUMPUR, HULU SELANGOR, KUALA LANGAT DAN KUALA SELANGOR 19 OKTOBER 2020 WILAYAH : PETALING ANGGARAN PEMULIHAN KAWASAN Kumpulan 1: Kumpulan 2: Kumpulan 3: Pulih Pulih Pulih BIL. KAWASAN sepenuhnya sepenuhnya sepenuhnya pada pada pada 8:00 pagi, 8:00 pagi, 8:00 -

Carey Island’S Port: Is It a “Need” Or “Want” ? Statement of Objectives

社会经济研究中心 SOCIO-ECONOMIC RESEARCH CENTRE Part 3: Carey Island’s port: Is it a “Need” or “Want” ? Statement of objectives • The idea of developing Carey Island’s port was conceptualised following the remarks that existing ports in the Port Klang area will hit maximum capacity. In early 2017, Port Klang Authority (PKA) had announced existing ports in the area will reach maximum capacity by 2025. • In April 2017, MMC Corporation Bhd has signed two agreements: (1) The first one with Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone Ltd (APSEZ) to conduct a feasibility study of Carey Island as an extension of Port Klang; and (2) Second MoU with Sime Darby Property Bhd and APSEZ to study the feasibility of developing an integrated maritime city in Carey Island. • In July 2018, another feasibility study under new administration will be independently conducted and commissioned by Port Klang Authority (PKA). As of now, previous government had not issued approval for the Carey Port. Transport Minister Anthony Loke indicated that the project will be private initiative-driven if the Parliament approved. • The objectives of this working paper are to provide an overview of the port development in Carey Island and also to assess the potential of the Carey Island project that can enhance the surrounding development. Socio-Economic Research Centre 1 Scope of the study Section 1: An overview of Carey Island • Illustrate some facts, the development status and hinterland connections about Carey Island. Section 2: Site and location analysis • Describe the land ownership of Carey Island, including an estimation of opportunity cost on Sime Darby Plantation’s arable land and palm oil revenue if Carey Port has to be implemented. -

P R O Je C T Op T Io N S

04 PROJECT OPTIONS Section 4 PROJECT OPTIONS SECTION 4 : PROJECT OPTIONS 4.1 INTRODUCTION Various alignment options were identified and evaluated in the process of selecting the preferred, optimum alignment for the Project. The options varied according to the physical characteristic, socio-economic constraints and transport network design requirements of each alignment options. In addition to the alignment options, two options for railway gauge were also considered, namely standard gauge and meter gauge. 4.2 PLANNING & DESIGN BASIS During the Feasibility Study for the ECRL Phase 2, a set of planning guidelines were used to develop the design concept for the ECRL Phase 2 corridor and the alignment (Table 4-1). Table 4-1 : Planning Guidelines for ECRL Phase 2 Aspect Description Strategic position Enhancing existing railway stations close to town centers to provide connectivity for freight transport Future development To avoid encroaching on areas committed for future development Connectivity Provide connectivity to: Major urban centers Industrial clusters Sea ports and internal container depot Tourism zones Integrated transport terminals Environment Minimize encroaching to Environmentally Sensitive Areas (ESAs) such as swamp forest, river corridors, forest reserves, ecological linkages and wildlife habitats wherever possible Additionally, a set of criteria will also be used to evaluate alignment options and to determine the preferred alignment ( Table 4-2). Section 5 Project Description 4-1 Table 4-2 : Alignment Criteria for ECRL -

Spatial Management Plan

6 -1 CHAPTER 6 SPATIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN The Spatial Management Plan is a basic framework that drives the translation of national strategic directions to the state level. The Spatial Management Plan consist of aspects related to spatial Three (3) Types of State Spatial availability (land use and transportation), growth areas (Conurbation, Management Plan Promoted Development Zone, Catalyst Centre and Agropolitan Centre), settlement hierarchies, resource management (forest, water, food, Spatial Growth Framework energy source and other natural resources) and disaster risk areas 1 Plan (tsunami, flood, landslide, coastal erosion and rise in sea level). Resource Management Plan A Spatial Management Plan at the state level is prepared to translate 2 national strategic directions to the state level (all states in Peninsular Natural Disaster Risk Area Malaysia, Sabah and Labuan Federal Territory) especially for strategic 3 Management Plan directions that have direct implications on a spatial aspect such as: . 1. Growth and development of cities as well as rural areas that is balanced and integrated (PD1 and PD 2); 2. Connectivity and access that is enhanced and sustainable (PD3); 3. Sustainable management of natural resources, food resources and State Spatial Management Plan heritage resources (KD1); involve the following states: 4. Management of risk areas (KD2); 5. Low carbon cities and sustainable infrastructure (KD3); and 1. Perlis pp. 6 - 8 6. Inclusive community development (KI1, KI2 and KI3). 2. Kedah pp. 6 - 14 3. Pulau Pinang pp. 6 - 20 This management plan shall become the basis for planning growth areas, conservation of resource areas as well as ensuring planning 4. Perak pp. 6 - 26 takes into account risks of natural disaster. -

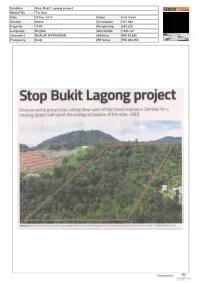

Stop Bukit Lagong Project

Headline Stop Bukit Lagong project MediaTitle The Star Date 03 Dec 2018 Color Full Color Section Metro Circulation 201,943 Page No 1TO3 Readership 605,829 Language English ArticleSize 1868 cm² Journalist SHALINI RAVINDRAN AdValue RM 99,650 Frequency Daily PR Value RM 298,950 Stop Bukit Lagong project Environmental groups say cutting down part of the forest reserve in Gombak for a housing project will upset the ecological balance of the area. >2&3 : ri:i tf Ii • i it** W W * --r<. - if : ,* •" Ml J&-V • J>. • Xi.' * — 1 xS rf^yz- rjsL ''' %J- ^Jf i-T, IS «.«« " 1, ««Hli^ar-S» s > 'fc-.ri" -ff. -tm'&rJiW ' HBi ; V „ •«'" • f/vVA.' • • Ti- fi L'-'O ' * . ; * • r • ; -mm^M r^sgp&L*. - v . 2 ::'; SL. ' ^ ' - ^ • • «fe- ^ i .-in < A. ^ .y I - • 4> A* ' O ' ' .V I^f JeJisr ^ » i 111 n i i t f n 111111 ri a tin 111 • i i 111111111111 u 111111111111111/ > i* Making way: An aerial view of the proposed housing development that would involve the degazetting of 28.3ha of the Bukit Lagong Forest Reserve in Gombak. — FAIHAN GHANI/The Star Headline Stop Bukit Lagong project MediaTitle The Star Date 03 Dec 2018 Color Full Color Section Metro Circulation 201,943 Page No 1TO3 Readership 605,829 Language English ArticleSize 1868 cm² Journalist SHALINI RAVINDRAN AdValue RM 99,650 Frequency Daily PR Value RM 298,950 STARMETRO, MONDAY 3 DECEMBER 2018 The pristine waterfall at Taman Rimba Bukit Lagong is one of the main attractions, the forest reserve also serves as an important water catchment area. -

Construction Aggregate Resources in the Federal Territory and Central Selangor

Geological Society of Malaysia Annual Geological Conference 2000 September 8-9 2000, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia Construction Aggregate Resources in the Federal Territory and Central Selangor CHEONG KHAI WENG & YEAP EE BENG Department of Geology, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Abstract The Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur and Selangor have produced 29% of the total crushed rock production in Malaysia. The average consumption per capita in 1998 was 3.74 tonnes of aggregates. It is estimated that the current rock reserve in this area can only cope with the demands of this region for the next 30 years. Thus, the exploitation of aggregate resources must be planned carefully and integrated with other types of landuse. Sumber Agregat Pembinaan di Wilayah Persekutuan dan Selangor Abstrak Wilayah Persekutuan Kuala Lumpur dan Selangor telah menghasilkan 29% daripada jumlah pengeluaran batu hancur di Malaysia. Jumlah penggunaan agregat per kapita pada tahun 1998 adalah 3.74 ton. Dianggarkan simpanan batuan sedia ada di kawasan ini hanya boleh memenuhi keperluan rantau ini untuk 30 tahun akan datang. Maka, eksploitasi sumber agregat mestilah dirancang dengan teliti dan disepadukan dengan jenis gunatanah yang lain. INTRODUCTION and provide plentiful construction aggregates to the Hulu Langat - Semenyih area. The areas around the Lagong Coarse aggregate is one of the most accessible natural Forest Reserve in the District of Gombak has currently industrial material and a major basic raw material used attracted a lot of quarry operators. One granite quarry in by the construction industry. It consists of crushed stone, Bukit Lanchong is stragetically located in a highly which is defined as "the product resulting from artificial populated area. -

SIME DARBY PLANTATION Sdn Bhd Management Unit SOU7 Jeram, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia

PUBLIC SUMMARY REPORT ANNUAL SURVEILLANCE ASSESSMENT (ASA1) SIME DARBY PLANTATION Sdn Bhd Management Unit SOU7 Jeram, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia Report Author Charlie Ross – Prepared June 2012 [email protected] Tel: +61 417609026 BSi Group Singapore Pte Ltd (Co. Reg. 1995 02096-N) BSi Services Malaysia Sdn Bhd (Co.Reg. 804473 A) 3 Lim Teck Kim Road #10-02 B-08-01, Level 8, Block B, PJ8 Genting Centre No. 23, Jalan Barat, Seksyen 8 SINGAPORE 088934 46050 Petaling Jaya Tel +65 6270 0777 SELANGOR MALAYSIA Fax +65 6270 2777 Tel +03 79607801 (Hunting Line) Aryo Gustomo: [email protected] Fax +03 79605801 www.bsigroup.sg ii TABLE of CONTENTS Page No SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................... 1 ABBREVIATIONS USED ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.0 SCOPE OF SURVEILLANCE ASSESSMENT ........................................................................................................ 1–6 1.1 Identity of Certification Unit ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Production Volume ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Certification Details ..................................................................................................................................... -

CASE STUDY of ROCK AGGREGATES in EASTERN SELANGOR Geological Society of Malaysia, Bulletin 53, June 2007, Pp

MINERALS SECURITY THROUGH LANDUSE PLANNING – CASE STUDY OF ROCK AGGREGATES IN EASTERN SELANGOR Geological Society of Malaysia, Bulletin 53, June 2007, pp. 89 – 93 Mineral security through landuse planning – Case study of rock aggregates in Eastern Selangor JOY JACQUELINE PEREIRA Institute for Environment and Development (LESTARI) Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia Abstract: There is a need to ensure long-term security for the supply of rock aggregates in Selangor, in view of the impending implementation of the Selangor Policy on Environmentally Sensitive Areas (ESAs). Preliminary findings from a case study of rock aggregates in Eastern Selangor reveal that six quarries and 66% of new aggregate resources in the state are located in highly sensitive ESAs, which are categorised as “no go areas” for quarrying. At least ten quarries and another 26% of new resources are located in ESAs of medium and low sensitivity, which are areas of “controlled development” requiring special circumstances and very strict conditions for quarrying. Only 8% of the new resources identified are actually available for exploitation in the future. Aggregate landbanks and buffer zones should be delineated and gazetted in local development plans and efforts should be made to thoroughly investigate potential resources outside of the ESAs. This effort should be augmented by the promotion of recycled concrete aggregates to maintain aggregate security and ensure sustainable development. Abstrak- Perlaksanaan Dasar Kawasan Sensitif Alam Sekitar (KSAS) Selangor dijangka menjejas jaminan bekalan batuan agregat di negeri tersebut. Hasil awalan kajian kes di bahagian timur Selangor mendapati bahawa terdapat enam kuari dan 66% daripada sumber aggregate baru yang bertapak di KSAS berkesensitifan tinggi yang melarang kegiatan pengkuarian. -

Executive Summary

EIA for the Proposed Mixed Development for Lagong Development at Mukim Rawang, Rev.01 District Of Gombak, Selangor Darul Ehsan for Sime Darby Landscaping Sdn. Bhd. RINGKASAN EKSEKUTIF I. Pengenalan Cadangan Projek Kajian EIA ini dijalankan untuk cadangan Pembangunan Bercampur di atas Lot 482, 484, 640, 688, 1423, 1424, 1000, 1020 & 1021, 1023, 1024, 1427, 1430, 1433 & 1876, 1434, 1436, 1437, 1439, 1440, 4157, 35227, 15361, 15360, 15359 dan 15358, Mukim Rawang, Lot 488, 489, 497 dan 498, Pekan Kuang, Daerah Gombak, Selangor Darul Ehsan. Projek ini akan dijalankan di kawasan dengan keluasan 1,549.45 ekar (627.04 hek). Tapak Projek ini adalah berpecah-pecah dan mempunyai dua kawasan pembangunan berbeza. Cadangan projek ini akan dibangunkan oleh Sime Darby Landscaping Sdn. Bhd. sebagai pemaju. Lokaliti tapak Projek ini adalah di bawah pentadbiran Majlis Perbandaran Selayang (MPS). Penilaian Awalan Tapak telah dikemukakan kepada Jabatan Alam Sekitar (JAS) Selangor pada 8hb Mei 2015 dan melalui surat bertarikh 20 Mei 2015 [(B) B 91/110 / 621/077 Jilid 185 (2)] Jabatan tidak mempunyai bantahan terhadap cadangan pembangunan. Sebagai maklumbalas kepada salah satu syarat yang dinyatakan dalam PAT, penukaran syarat nyata tanah untuk tapak akan dilakukan setelah mendapat kelulusan penyerahan KM dan di bawah proses serahan dan pemberimilikan semula. Jabatan juga meminta penyediaan dan penyerahan laporan EIA ke Jabatan Alam Sekitar, Selangor untuk pembangunan yang dicadangkan. Tapak Projek ini terletak di dalam Mukim Rawang dan Pekan Kuang, Selangor Darul Ehsan. Terdapat tiga lebuhraya utama yang melaului Tapak Projek yang dicadangkan ini iaitu Guthrie Corridor Expressway (GCE-E35 Shah Alam – Rawang Expressway), Lebuhraya Utara Selatan (E1) and Lebuhraya Kuala Lumpur – Kuala Selangor E25 (LATAR). -

2. Soalan Bertulis

PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN BERTULIS DARIPADA Y.B. PUAN HANIZA BT. MOHAMED TALHA (TAMAN MEDAN) TAJUK : PELABURAN DAN PELUANG PEKERJAAN DALAM SELANGOR 1. Bertanya kepada Y.A.B. Menteri Besar: a) Nyatakan dengan terperinci mengenai pelaburan baru yang diperoleh bagi 2009-2010. b) Senaraikan bilangan peluang pekerjaan yang ada di seluruh Selangor. c) Apakah usaha kerajaan bagi memastikan pekerjaan tersebut diisi oleh warga Malaysia? JAWAPAN : a) Bagi tempoh Januari hingga Disember 2009 sebanyak 182 projek baru telah diluluskan oleh MIDA di Selangor dengan nilai pelaburan berjumlah RM 3,181,707,948. Daripada jumlah ini, sebanyak RM 1,893,920,504 adalah daripada pelaburan tempatan dan sebanyak RM 1,287,787,444 daripada pelaburan asing. Sebanyak 14,483 potensi peluang pekerjaan telah diwujudkan. b) Bagi tempoh Januari hingga Disember 2009, sebanyak 22,753 potensi peluang pekerjaan telah diwujudkan di Negeri Selangor hasil daripada 278 projek perkilangan yang diluluskan. Daripada jumlah ini sebanyak 14,483 potensi peluang pekerjaan daripada projek baru dan selebihnya sebanyak 8,270 potensi peluang pekerjaan daripada projek pembesaran/pelbagaian. c) Bagi memastikan peluang-peluang pekerjaan ini diisi, Kerajaan Negeri telah mengadakan program “Jom Kerja” yang mana program ini memberi kesempatan kepada pihak syarikat untuk mengadakan “walk in interview” di tempat program ini diadakan. Program ini akan diadakan di setiap daerah bagi membantu pihak syarikat mencari sumber tenaga kerja yang diperlukan di kalangan rakyat tempatan. SSIC Berhad juga turut menganjurkan pertemuan dengan Ketua-Ketua Kampung, Guru- Guru Besar Sekolah dan Pengarah Institut Kemahiran Belia untuk mendapatkan kerjasama mereka bagi menghebahkan kekosongan pekerja bersama-sama kilang- kilang yang memerlukan pekerja dan juga Pejabat Daerah. -

Direktori Florikultur Malaysia

DIREKTORI FLORIKULTUR MALAYSIA 2016 JABATAN PERTANIAN MALAYSIA JABATAN PERTANIAN MALAYSIA 1 | P a g e DIREKTORI PENGUSAHA FLORIKULTUR BPTIF, JABATAN PERTANIAN 2017 KANDUNGAN PERKARA MUKA SURAT 1. PRAKATA 2. PENDAHULUAN 3. OBJEKTIF 4. RINGKASAN MAKLUMAT FLORIKULTUR MENGIKUT NEGERI 5. RINGKASAN MAKLUMAT FLORIKULTUR MENGIKUT PERSATUAN BUNGA TAHUN 2016 6. MAKLUMAT ASAS PENGUSAHA FLORIKULTUR 5.1 NEGERI PERLIS & DAERAH 5.2 NEGERI KEDAH & DAERAH 5.3 NEGERI PULAU PINANG & DAERAH 5.4 NEGERI PERAK & DAERAH 5.5 NEGERI SELANGOR & DAERAH/ WPKL 5.6 NEGERI SEMBILAN & DAERAH 5.7 NEGERI MELAKA & DAERAH 5.8 NEGERI JOHOR & DAERAH 5.9 NEGERI KELANTAN & DAERAH 5.10 NEGERI TERENGGANU & DAERAH 5.11 NEGERI PAHANG & DAERAH 5.12 NEGERI SABAH & DAERAH 5.13 NEGERI SARAWAK & DAERAH 7. LAMPIRAN 2 | P a g e DIREKTORI PENGUSAHA FLORIKULTUR BPTIF, JABATAN PERTANIAN 2017 PENDAHULUAN Malaysia mempunyai kelebihan dari segi kekayaan biodiversiti berupaya menjana dan meningkatkan sumbangan industri fllorikultur kepada pendapatan Negara. Dalam tempoh pelaksanaan Dasar Agromakanan Negara (DAN), jumlah pengeluaran bunga negara dijangka meningkat daripada 468 juta keratan atau pasu pada tahun 2020 iaitu pertumbuhan sebanyak 6.2% setahun. Nilai eksport forikultur pula diunjurkan meningkat daripada RM449 juta pada tahun 2010 kepada RM857 juta pada tahun 2020. Penubuhan Jawatankuasa Food and Agro Council for Export (FACE) bagi menyelaras pelaksanaan pengeluaran untuk eksport bagi agromakanan diharapkan mampu meningkatkan eksport agromakanan negara. Malaysian Agro Networking (MAN) mengikut subsektor tanaman iaitu buah-buahan, sayur-sayuran dan florikultur telah ditubuhkan melalui beberapa siri perbincangan dengan pihak Persatuan Pengeluar Subsektor Tanaman. MAN (Florikultur) berperanan sebagai medium perbincangan di antara Jabatan Pertanian dan Jabatan/ Agensi berkaitan dengan pemain industri bagi meningkatan pengeluaran florikultur khususnya bagi tujuan eksport. -

Major News Property Launches

Property launches ECONOMIC OVERVIEW Apartments / Condos / Townhouses Key statistics Latest release Previous rate Single storey terraced houses Two storey terraced houses Quarterly GDP growth 4.0% (2Q2011) 4.6% (1Q2011) Three storey terraced houses Annual GDP growth 7.2% (2010) -1.7%(2009) Three storey semi-d houses Two storey detached houses Consumer Price Index (CPI) 3.3% (Aug-11) 3.1% (Jul-11) Two & half detached houses Industrial Production Index (IPI) 107.5 (Jul-11) 108.0 (June-11) Three storey detached houses Base Lending Rate (BLR) 6.60% (May-11) 6.27% (Apr-11) Major News Exchange rate: RM to US dollar RM3.1910 (30/09) RM2.9700 (01/09) Vue woos prospective buyers with… Source: Department of Statistics Malaysia & Bank Negara Malaysia Canada, Australia next on TA Global… Bukit OUG condominium owners… New HELP campus to be ready by 2013 The Malaysia’s economy recorded a growth of 4.0% during the second quarter of SunREIT to double value of Putra Place 2011. Services sector was the main contributor to the economic growth. The key Laman PKNS to aim for GBI Platinum impetus on the demand side was the Private Final Consumption Expenditure. Kedah Hydrocarbon Hub back on track During the first six months of 2011, the Gross Domestic Products (GDP) expanded by 4.4%. LBS to launch high-end RM3.5bil… Magna Prima in A$210m Aussie… The Consumer Price Index (CPI) accelerated by 3.3% year-on-year in August, on River of Life in full flow higher prices for miscellaneous goods and services, recreation services and PR1MA sites located culture as well as housing, water, electricity, gas and other fuels.