Winter Readings • Air Base Attack in Desert Storm • Iraqi Air Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operation Iraqi Freedom

Operation Iraqi Freedom: A First-Blush Assessment Andrew F. Krepinevich 1730 Rhode Island Avenue, NW, Suite 912 Washington, DC 20036 Operation Iraqi Freedom: A First-Blush Assessment by Andrew F. Krepinevich Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments 2003 ABOUT THE CENTER FOR STRATEGIC AND BUDGETARY ASSESSMENTS The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments is an independent public policy research institute established to promote innovative thinking about defense planning and investment strategies for the 21st century. CSBA’s analytic-based research makes clear the inextricable link between defense strategies and budgets in fostering a more effective and efficient defense, and the need to transform the US military in light of the emerging military revolution. CSBA is directed by Dr. Andrew F. Krepinevich and funded by foundation, corporate and individual grants and contributions, and government contracts. 1730 Rhode Island Ave., NW Suite 912 Washington, DC 20036 (202) 331-7990 http://www.csbaonline.org ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to thank Steven Kosiak, Robert Martinage, Michael Vickers and Barry Watts, who reviewed several drafts of this report. Their comments and suggestions proved invaluable. Critical research assistance was provided by Todd Lowery. His support in chasing down numerous sources and confirming critical facts proved indispensable. Alane Kochems did a fine job editing and proofing the final report draft, while Alise Frye graciously helped craft the report’s executive summary. I am most grateful for their encouragement and support. Naturally, however, the opinions, conclusions and recommendations in this report are the sole responsibility of the author. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... I I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 II. STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS ........................................................................................ -

Echan La Culpa a Las Lluvias De Lo Caras Que Están Las Frutas

PREMIO NACIONALDOMINGO DE PERIODISMO 1982 / 1989 / 1990 EL PERIÓDICO DEL PUEBLO ORIENTAL PUERTO LA CRUZ, Do m i ng o 27 de mayo de 2012 WW W.ELTIEMPO.COM.VE AÑO LII - Nº 2 0. 14 5 PRECIO Bs 4,00 DE P O RT E S CO N S U M O > Vendedores dicen que el mal estado de las vías contribuye al encarecimiento de productos Echan la culpa a las lluvias de lo caras El Marinos de 1991 dio inicio a la devoción que están las frutas de la fanaticada La lechosa, las naranjas y la guayaba son los rubros frutales que más han aumentado de precio en las últimas semanas. Los expendedores ubicados en el mercado municipal de Sotillo y en sus orient al +36, 37 alrededores aducen que pierden con algunos de ellos, como el melón, porque se dañan con rapidez. DRENAJES MEDIOS El Indepabis asegura que velará porque los proveedores no abusen >> 3 Por un tiempo más Hace cinco años Sotillo padecerá entró Tves y salió las consecuencias Rctv de la señal NI EL SÁBADO SE SALVAN de las lluvias del canal 2 +8 ,9 +1 6,1 7 EN CU E N T RO MUNDO Un exrehén está bajo sospecha por su presunta co l a b o ra c i ó n con las Farc +20 Niños de Anaco SALU D t u v i e ro n Clínicas plantean una jornada reanudar diálogo de pintura sobre costos con Caballito de sus servicios +30 +5 Una gran cola, de horas, se formó ayer en la vía sentido Barcelona-Puerto La Cruz, que no sólo impidió el acceso en esa dirección sino también hacia el hospital Luis Razetti. -

Air Force Enlisted Personnel Policy 1907-1956

FOUNDATION of the FORCE Air Force Enlisted Personnel Policy 1907-1956 Mark R. Grandstaff DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A Approved for Public Release Distribution Unlimited AIR PROGRAM 1997 20050429 034 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Grandstaff, Mark R. Foundation of the Force: Air Force enlisted personnel policy, 1907-1956 / Mark R. Grandstaff. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. United States. Air Force-Non-commissioned officers-History. 2. United States. Air Force-Personnel management-History. I. Title. UG823.G75 1996 96-33468 358.4'1338'0973-DC20 CIP For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-9328 ISBN 0-16-049041-3 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGEFomApve OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information Is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of Information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. -

Programs Issue 2018 Flyer Daedalian Flying Training

Daedalus Programs Issue 2018 Flyer Daedalian Flying Training Educ & Trng Awards Veterans Day JROTC Awards Service Awards ROTC Scholarships Aviation Awards Air Camp Community Support First to fly in time of war The premier fraternity of military aviators CONTENTS December 2018, Vol. LIX No. 4 Departments Programs 5 8 30-31 Reunions Objectives & Programs Service Awards 6 10 32-33 Commander’s Perspective Meet the Program Manager Mentoring Program 7 11 34-35 Executive Director Top 10 Benefits of Membership Virtual Flight 14 12-13 36-37 New/Rejoining Daedalians A Daedalian History Lesson A Tribute to Les Leavoy 16-17 15 38-39 Book Reviews Education & Training Awards Air Camp 23 19 40-41 In Memoriam Sustained Giving JROTC Awards 42-44 20-21 Awards Community Support Extras 18 45-63 22 Advice for Future Aviators Flightline National Flight Academy 64 65 24-25 A Young Boy’s Wisdom Flight Contacts Scholarships 66-67 26-27 Eagle Wing DFT 28-29 Educate Americans THE ORDER OF DAEDALIANS was organized on March 26, 1934, by a representative group of American World War I pilots to perpetuate the spirit of pa- triotism, the love of country, and the high ideals of sacrifice which place service to nation above personal safety or position. The Order is dedicated to: insuring that America will always be preeminent in air and space—the encouragement of flight safety—fostering an esprit de corps in the military air forces—promoting the adoption of military service as a career—and aiding deserving young individuals in specialized higher education through the establishment of scholarships. -

Impact Melt Emplacement on Mercury

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 7-24-2018 2:00 PM Impact Melt Emplacement on Mercury Jeffrey Daniels The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Neish, Catherine D. The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Geology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Science © Jeffrey Daniels 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Geology Commons, Physical Processes Commons, and the The Sun and the Solar System Commons Recommended Citation Daniels, Jeffrey, "Impact Melt Emplacement on Mercury" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5657. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5657 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Impact cratering is an abrupt, spectacular process that occurs on any world with a solid surface. On Earth, these craters are easily eroded or destroyed through endogenic processes. The Moon and Mercury, however, lack a significant atmosphere, meaning craters on these worlds remain intact longer, geologically. In this thesis, remote-sensing techniques were used to investigate impact melt emplacement about Mercury’s fresh, complex craters. For complex lunar craters, impact melt is preferentially ejected from the lowest rim elevation, implying topographic control. On Venus, impact melt is preferentially ejected downrange from the impact site, implying impactor-direction control. Mercury, despite its heavily-cratered surface, trends more like Venus than like the Moon. -

Forever Free Mckinney

FOREVER FREE MCKINNEY By Christopher Rozansky Collin County Regional Airport January - February The City of McKinney’s Fourth of 2008 July celebration, Forever Free, was delayed five weeks last FOREVER FREE MCKINNEY 1, 3 summer, but if you asked 88 wounded soldiers they would not DAVE’S HANGAR 2 have wanted it any other way. More than 20 inches of summer WINGTIPS EDITOR ON TO RETIREMENT rainfall dampened the spirits of A C-130, one of two aircraft, carrying 88 veterans arrives at McKinney-Collin 2 those who were looking forward County Regional Airport and is greeted by a ceremonial arch of water courtesy to the music and fireworks display of the airport’s fire department. TEXAS AVIATION HALL OF FAME scheduled to be held at Myers 3-4 Park. Wet conditions forced planners to postpone the event until August 11, 2007, but that setback ALPINE CASPARIS turned out to be a unique opportunity for the community and Collin County Regional Airport to honor MUNICIPAL AIRPORT veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. 5-7 WASP MOTTO U.S. Department of Defense staff from the Office of the Severely Injured Joint Support Operations 7-8 Center, a program created several years ago to support those injured in combat, learned of the TXDOT’S 26TH ANNUAL circumstances and contacted event planners. All involved recognized the significance of the AVIATION CONFERENCE 9-12 opportunity before them and moved quickly to integrate a fitting tribute to those who have fought for our freedom with the delayed Independence Day celebration. With a plan put together in only a couple SAVORING STEPHENVILLE 13-14 of short weeks, all that was needed was a sunny forecast. -

World Air Forces Flight 2011/2012 International

SPECIAL REPORT WORLD AIR FORCES FLIGHT 2011/2012 INTERNATIONAL IN ASSOCIATION WITH Secure your availability. Rely on our performance. Aircraft availability on the flight line is more than ever essential for the Air Force mission fulfilment. Cooperating with the right industrial partner is of strategic importance and key to improving Air Force logistics and supply chain management. RUAG provides you with new options to resource your mission. More than 40 years of flight line management make us the experienced and capable partner we are – a partner you can rely on. RUAG Aviation Military Aviation · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen · Switzerland Legal domicile: RUAG Switzerland Ltd · Seetalstrasse 175 · P.O. Box 301 · 6032 Emmen Tel. +41 41 268 41 11 · Fax +41 41 260 25 88 · [email protected] · www.ruag.com WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 CONTENT ANALYSIS 4 Worldwide active fleet per region 5 Worldwide active fleet share per country 6 Worldwide top 10 active aircraft types 8 WORLD AIR FORCES World Air Forces directory 9 TO FIND OUT MORE ABOUT FLIGHTGLOBAL INSIGHT AND REPORT SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES, CONTACT: Flightglobal Insight Quadrant House, The Quadrant Sutton, Surrey, SM2 5AS, UK Tel: + 44 208 652 8724 Email:LQVLJKW#ÁLJKWJOREDOFRP Website: ZZZÁLJKWJOREDOFRPLQVLJKt World Air Forces 2011/2012 | Flightglobal Insight | 3 WORLD AIR FORCES 2011/2012 The French and Qatari air forces deployed Mirage 2000-5s for the fight over Libya JOINT RESPONSE Air arms around the world reacted to multiple challenges during 2011, despite fleet and budget cuts. We list the current inventories and procurement plans of 160 nations. -

Airport Listings of General Aviation Airports

Appendix B-1: Summary by State Public New ASSET Square Public NPIAS Airports Not State Population in Categories Miles Use Classified SASP Total Primary Nonprimary National Regional Local Basic Alabama 52,419 4,779,736 98 80 75 5 70 18 25 13 14 Alaska 663,267 710,231 408 287 257 29 228 3 68 126 31 Arizona 113,998 6,392,017 79 78 58 9 49 2 10 18 14 5 Arkansas 53,179 2,915,918 99 90 77 4 73 1 11 28 12 21 California 163,696 37,253,956 255 247 191 27 164 9 47 69 19 20 Colorado 104,094 5,029,196 76 65 49 11 38 2 2 27 7 Connecticut 5,543 3,574,097 23 19 13 2 11 2 3 4 2 Delaware 2,489 897,934 11 10 4 4 1 1 1 1 Florida 65,755 18,801,310 129 125 100 19 81 9 32 28 9 3 Georgia 59,425 9,687,653 109 99 98 7 91 4 18 38 14 17 Hawaii 10,931 1,360,301 15 15 7 8 2 6 Idaho 83,570 1,567,582 119 73 37 6 31 1 16 8 6 Illinois 57,914 12,830,632 113 86 8 78 5 9 35 9 20 Indiana 36,418 6,483,802 107 68 65 4 61 1 16 32 11 1 Iowa 56,272 3,046,355 117 109 78 6 72 7 41 16 8 Kansas 82,277 2,853,118 141 134 79 4 75 10 34 18 13 Kentucky 40,409 4,339,367 60 59 55 5 50 7 21 11 11 Louisiana 51,840 4,533,372 75 67 56 7 49 9 19 7 14 Maine 35,385 1,328,361 68 36 35 5 30 2 13 7 8 Maryland 12,407 5,773,552 37 34 18 3 15 2 5 6 2 Massachusetts 10,555 6,547,629 40 38 22 22 4 5 10 3 Michigan 96,716 9,883,640 229 105 95 13 82 2 12 49 14 5 Minnesota 86,939 5,303,925 154 126 97 7 90 3 7 49 22 9 Mississippi 48,430 2,967,297 80 74 73 7 66 10 15 16 25 Missouri 69,704 5,988,927 132 111 76 4 72 2 8 33 16 13 Montana 147,042 989,415 120 114 70 7 63 1 25 33 4 Nebraska 77,354 1,826,341 85 83 -

47Th FLYING TRAINING WING

47th FLYING TRAINING WING MISSION The 47th Flying Training Wing conducts joint specialized undergraduate pilot training for the United States Air Force, Air Force Reserve, Air National Guard and allied nation air forces utilizing the T-37, T-38 and T-1A aircraft. The 47th FTW commands a flying operation which exceeds 105,000 flying hours and 90,000 sorties per year. It is composed of more than 1,300 military personnel, 1,124 civilian employees and a total base community exceeding 4,200 people. LINEAGE 47th Bombardment Wing, Light, established, 28 Jul 1947 Organized, 15 Aug 1947 Inactivated, 2 Oct 1949 Activated, 12 Mar 1951 Redesignated 47th Bombardment Wing, Tactical, 1 Oct 1955 Discontinued and inactivated, 22 Jun 1962 Redesignated 47th Flying Training Wing, 22 Mar 1972 Activated, 1 Sep 1972 STATIONS Biggs Field (later, AFB), TX, 15 Aug 1947 Barksdale AFB, LA, 19 Nov 1948-2 Oct 1949 Langley AFB, VA, 12 Mar 1951-21 May 1952 Sculthorpe RAF Station (later, RAF Sculthorpe), England, 1 Jun 1952-22 Jun 1962 Laughlin AFB, TX, 1 Sep 1972 ASSIGNMENTS Twelfth Air Force, 15 Aug 1947-2 Oct 1949 Tactical Air Command, 12 Mar 1951 Third Air Force, 5 Jun 1952 Seventeenth Air Force, 1 Jul 1961-22 Jun 1962 Air Training Command, 1 Sep 1972 Nineteenth Air Force, 1 Jul 1993 ATTACHMENTS 49th Air Division, Operational, l2 Feb 1952-1 Jul 1956 WEAPON SYSTEMS A (later, B)-26, 1947 B-45, 1949 B-45, 1951 B-26, 1951 RB-45, 1954 B-66, 1958 KB-50, 1960 T-41, 1972 T-37, 1972 T-38, 1972 T-1, 1993 T-6, 2002 COMMANDERS Col William M. -

Optics, Aesthetics, Epistemology : the History of Photography Reconsidered

OPTICS, AESTHETICS, EPISTEMOLOGY: THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY RECONSIDERED Peter Wollheim B.A., University of Rochester, 1970 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS (COWNICATION STUDIES) in the Department of Communication Studies @ Peter Wollheim 1977 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY November 1977 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Approval Name: Peter Wollheirn Degree: Master of Arts (Communication Studies) Title of Thesis: "Optics, Aesthetics, Epistemology: The History of Photography Reconsidered." Examining Committee: Chairperson: Thomas J. Mallinson J. C. Haqpr - Supervisor J. Zaslove E. Gibson EMrnal Examiner Associate Professor Department of Geography, Simon Fraser University Date Approved : November 29th.1977. PARTIAL COPYRTCHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to usere of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to marte parclai or singie copies only for. such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its 'own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/~issertation: "OPTICS AESTHETICS, EPISTEMOLOGY: THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY RFXONS IDERED" Author : (signature) PETER WOLLHFIM (name) NQV: 23rd. 1977 (date) This thesis dfals with the status of "truthi' - spis+;mological, assthhetic, and psycholcgical - % r. -

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 48

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 48 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2010 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All ri hts reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information stora e and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Printed by Windrush Group ,indrush House Avenue Two Station Lane ,itney O028 40, 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President 2arshal of the Royal Air Force Sir 2ichael 3eetham GC3 C3E DFC AFC 7ice8President Air 2arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KC3 C3E AFC Committee Chairman Air 7ice82arshal N 3 3aldwin C3 C3E FRAeS 7ice8Chairman -roup Captain 9 D Heron O3E Secretary -roup Captain K 9 Dearman FRAeS 2embership Secretary Dr 9ack Dunham PhD CPsychol A2RAeS Treasurer 9 Boyes TD CA 2embers Air Commodore - R Pitchfork 23E 3A FRAes :9 S Cox Esq BA 2A :6r M A Fopp MA F2A FI2 t :-roup Captain A 9 Byford MA MA RAF :,ing Commander P K Kendall BSc ARCS MA RAF ,ing Commander C Cummings Editor & Publications ,ing Commander C G Jefford M3E BA 2ana er :Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS OPENIN- ADDRESS œ Air 2shl Ian Macfadyen 7 ON.Y A SIDESHO,? THE RFC AND RAF IN A 2ESOPOTA2IA 1914-1918 by Guy Warner THE RAF AR2OURED CAR CO2PANIES IN IRAB 20 C2OST.YD 1921-1947 by Dr Christopher Morris No 4 SFTS AND RASCHID A.IES WAR œ IRAB 1941 by )A , Cdr Mike Dudgeon 2ORNIN- Q&A F1 SU3STITUTION OR SU3ORDINATION? THE E2P.OY8 63 2ENT OF AIR PO,ER O7ER AF-HANISTAN AND THE NORTH8,EST FRONTIER, 1910-1939 by Clive Richards THE 9E3E. -

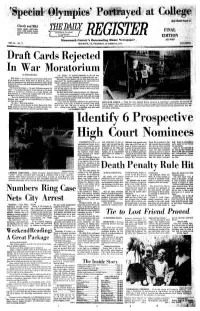

Identify 6 Prospective High Court Nominees WASHINGTON (AP) - a Nent Assignment in This Re- California State Appeals Court Nixon

Cloudy and Mild Mostly cloudy, mild today. THEDAILY Clear, mild tonight; Sunny, pleasant tomorrow and Satur- FINAL day. EDITION Monmouth County's Outstanding Home X«?wspa|»c*r 32 PAGES VOL. 94 NO. 77 BED BANK, IS J. THURSDAY, OCTOBEK M,1971 Draft Cards Rejected In War Moratorium By DOBIS KULMAN "Mr. Dilapo?" he inquired pleasantly as the two men 1 shook hands, "I'm Larry Erickson. I've wanted to meet you." RED BANK — Two young men turned in their draft cards "When you go home tonight, why not think about why you're at the Selective Service Board office on Broad St., here, as doing this?" Mr, prkkson .suggested to the board staff as he* part of 3 Moratorium Day observance yesterday while a group and Mr. Gurniak left to rejoin the demonstrators. of about 150 anti-war, anti-draft demonstrators picketed on the Mr. Erickson also, turned in the draft card of Bic Kcssler, sidewalk below. formerly of Fair Haven, which he said Mr. Kcssler had given The chant of the pickets - "no more Victnams, no more At- him for that purpose. He said Mr. Kessler is believed en route , ticas" -~ was audible through the closed windows of the board here from Boulder, Colo. offices as Lawrence D. Erickson, 22, of Long Branch, arid The draft board wasn't taken by surprise, Mr. Dilapo said. Greg Gurniak, 21, of Red Bank, dropped their draft cards on He said he had read nowspaper reports quoting Mr. Erick- the desk of Joan Dixon, a board secretary, son as saying he would return his own draft card and would j "There are demonstrators outside against the draft," Mr.