A COMPARATIVE ANATOMY of OIL PRICE ROUTS: a REVIEW of FOUR PRICE ROUTS BETWEEN 1985 and 2014 Robert Skinner†

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monthly Report on Petroleum Developments in the World Markets February 2020

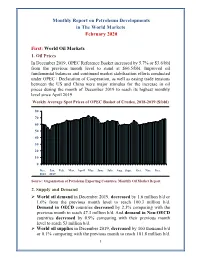

Monthly Report on Petroleum Developments in The World Markets February 2020 First: World Oil Markets 1. Oil Prices In December 2019, OPEC Reference Basket increased by 5.7% or $3.6/bbl from the previous month level to stand at $66.5/bbl. Improved oil fundamental balances and continued market stabilization efforts conducted under OPEC+ Declaration of Cooperation, as well as easing trade tensions between the US and China were major stimulus for the increase in oil prices during the month of December 2019 to reach its highest monthly level since April 2019. Weekly Average Spot Prices of OPEC Basket of Crudes, 2018-2019 ($/bbl) 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Dec. Jan. Feb. Mar. April May June July Aug. Sept. Oct. Nov. Dec. 2018 2019 Source: Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, Monthly Oil Market Report. 2. Supply and Demand World oil demand in December 2019, decreased by 1.6 million b/d or 1.6% from the previous month level to reach 100.3 million b/d. Demand in OECD countries decreased by 2.3% comparing with the previous month to reach 47.3 million b/d. And demand in Non-OECD countries decreased by 0.9% comparing with their previous month level to reach 53 million b/d. World oil supplies in December 2019, decreased by 100 thousand b/d or 0.1% comparing with the previous month to reach 101.8 million b/d. 1 Non-OPEC supplies remained stable at the same previous month level of 67.2 million b/d. Whereas preliminary estimates show that OPEC crude oil and NGLs/condensates total supplies decreased by 0.6% comparing with the previous month to reach 34.5 million b/d. -

Price Forecast June 30, 2015 Contents

Resource Evaluation & Advisory Price forecast June 30, 2015 Contents Canadian price forecast 1 International price forecast 5 Global outlook 6 Western Canada royalty comparison 8 Pricing philosophy 11 Glossary 12 Canadian domestic price forecast Forecast commentary Andrew Botterill Senior Manager, Resource Evaluation & Advisory “Everything is in a state of fl ux, including status quo” - Robert Byrne As industry adjusts to the “new normal” we have analyzed This narrowing has been most notable on the heavy oil in our last two forecasts, activities in the energy sector side, where diff erentials have decreased more than 30 per are beginning to demonstrate a cautious, but optimistic cent compared with where they were in summer 2014. view of the future. While not anticipating $100 oil in the With greater than 60 per cent of Canadian production near term, these views show an expectation industry will being from oil sands (CAPP 2015 forecast report) the bring a more focused approach to North American oil narrowing of heavy diff erentials is welcome news to much development within the coming 12 to 18 months. of the sector. In recent weeks, the WTI to heavy diff erential has been narrower than we have seen recently as In recent weeks, Canadian-received oil prices have been production from some projects was shut-in due to wildfi res stronger relative to the beginning of the year, with daily in northern Alberta. The shut-in production has since been WTI settlements hovering around $60/bbl USD and brought back on-stream, which has slowed the narrowing Canadian Light settlements greater than $70/bbl CAD. -

The Price of Oil Risk

The Price of Oil Risk Steven D. Baker,∗ Bryan R. Routledge,y [February 10, 2017] Abstract We solve a Pareto risk-sharing problem for two agents with heterogeneous re- cursive utility over two goods: oil, and a general consumption good. Using the optimal consumption allocation, we derive a pricing kernel and the price of oil and related futures contracts. This gives us insight into the dynamics of prices and risk premia. We compute portfolios that implement the optimal consumption policies, and demonstrate that large and variable open interest is a property of optimal risk-sharing. A numerical example of our model shows that rising open interest and falling oil risk premium are an outcome of the dynamic properties of the optimal risk sharing solution. ∗ McIntire School of Commerce, University of Virginia; [email protected]. y Tepper School of Business, Carnegie Mellon University; [email protected]. 1 Introduction The spot price of crude oil, and commodities in general, experienced a dramatic price increase in the summer of 2008. For oil, the spot price peaked in early July 2008 at $145.31 per barrel (see Figure 1). In real-terms, this price spike exceeded both of the OPEC price shocks of 1970's and has lasted much longer than the price spike at the time of the Iraq invasion of Kuwait in the summer of 1990. The run-up to the July 2008 price of oil begins around 2004. Buyuksahin, Haigh, Harris, Overdahl, and Robe (2011) and Hamilton and Wu (2014) identify a structural change in the behavior of oil prices around 2004. -

The Impact of the U.S Fracking Boom on the Price of Oil and on Arab Oil Producers

The Impact of the U.S Fracking Boom on the Price of Oil and on Arab Oil Producers Lutz Kilian University of Michigan CEPR Background ● Shale oil production became possible because of technological innovation (horizontal drilling, hydraulic fracturing (fracking), microseismic imaging). ● The rapid expansion of U.S. shale oil production was stimulated by the high price of conventional crude oil after 2003, which made this new technology competitive. ● Since then efficiency gains in shale oil production have lowered its cost, allowing continued production at much lower oil prices. ● Because the price of oil has remained low since 2015, shale oil producers are experiencing increased operating losses and financial stress. The Role of Refineries ● Crude oil is being consumed by refineries that turn crude oil into refined products such as gasoline, diesel, heating oil, jet fuel and heavy fuel oil. ● Not all refineries are alike. Their technical configuration determines which type of crude oil they can process. ● Changing an existing configuration is costly. The Refining Industry in Transition A few years ago, the global refining industry expected a growing shortage of light sweet crude oil worldwide: 1. Refiners along the Texas Gulf Coast invested in new technology that allowed them to become the world leader in processing heavier crudes. This allowed them to process lower priced crudes imported from Saudi Arabia, Venezuela and Mexico. 2. Refiners along the East Coast began to shut down existing refineries for light sweet crude oil in anticipation of a growing shortage of light sweet crude oil. The Glut That No One Saw Coming After 2010 shale oil was shipped in ever increasing quantities from the interior of the country to the U.S. -

Peak Oil Demand and Long-Run Oil Prices

January 2018 Peak Oil Demand and Long-Run Oil Prices Abstract The prospect that global oil demand will gradually slow and eventually peak has created a cottage industry of executives and commentators trying to predict the point at which demand will peak. In this Energy Insight, we argue that this focus seems misplaced. The date at which oil demand will stop growing is highly uncertain and small changes in assumptions can lead to vastly different estimates. More importantly, there is little reason to believe that once it does peak, that oil demand will fall sharply. The world is likely to demand large quantities of oil for many decades to come. Rather, the significance of peak oil is that it signals a shift in paradigm – from an age of (perceived) scarcity to an age of abundance – and with it is likely to herald a shift to a more competitive market environment. This change in paradigm is also likely to pose material challenges for oil producing economies as they try both to ensure that their oil is produced and consumed, and at the same time diversify their economies fit for a world in which they can no longer rely on oil revenues to provide their main source of revenue for the indefinite future. We argue that the extent and pace of this diversification is likely to have an important bearing on oil prices over the next 20 or 30 years. It seems likely that many low-cost producers will delay the pace at which they adopt a more competitive “higher volume, lower price” strategy until they have made material progress in reforming their economies. -

Embassy - Canada's

<b> Searching for a Pakistan policy </b> | Embassy - Canada's ... http://www.embassymag.ca/page/printpage/pakistan-9-23-2009 embassymag.ca September 23, 2009 - http://embassymag.ca/page/printpage/pakistan-9-23-2009 Searching for a Pakistan policy By Lee Berthiaume On a cold winter morning in mid-January, about 90 academics, journalists, former political leaders and diplomats gathered in a room in the Ottawa headquarters of Canada's spy agency, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service. While drawn from different backgrounds, they all shared one thing in common: deep interest or expertise in Pakistan. The next two days were spent discussing the factors that had contributed to the South Asian country being named one of the most dangerous countries in the world in terms of global stability. The participants also laid out possible scenarios for Pakistan's future. The main ideas were captured in a report that would support "the Embassy Photo: Lee Berthiaume development of an informal community of interest on Pakistan's Pakistan High Commissioner Akbar Zeb says his security within the government of Canada." country wants the Canadian government to start working on a free trade agreement with his country, Yet noticeably absent from the report were any policy suggestions for increase aid and lift arms trading restrictions. Canada, whose own interest in Afghanistan's nuclear-armed neighbour cannot be understated. In fact, the only real mention of Canada came in explaining the implications Pakistan's deteriorating security situation would have on Canada. Eight years after 9/11 put Pakistan on the front lines of the global war on terror, critics say the government has failed to fully grasp the need for a comprehensive policy towards the country. -

Welcome to the 11Th Edition of Energy Perspectives! This Is An

Welcome to the 11th edition of Energy Perspectives! This is an independent report that informs Equinor’s strategy and offers a fact-based contribution to the energy transition debate. This year’s edition is an update of the edition from November last year, and with a lot happening on the global arena the last 6 months, there is a lot to consider when looking 30 years ahead. As always, this report and its data and conclusions would be impossible without the excellent work of many of my colleagues, to whom I extend my appreciation and gratitude. You are the best! 1 Covid19 is not over. In a global perspective, we are still dealing with its impact and the enormous effects it has on people, societies, economies, and markets. We are not through it yet. And we might have to live with recurring infection spikes, especially in parts of the world that do not get sufficient access to vaccines. Recurring lockdowns entailed that energy demand, and in particular oil demand due to its use as a transport fuel, was hit hard. Recovery is in the making, and faster than many feared, but oil demand, as an example, is still not back to pre-Covid19-levels. The map shows how the pandemic has affected economies across the globe, with almost all countries pink or red, that is, with negative economic development. Industrialised countries are on their way out of recession while disabling the virus, but the uncertainty is still high in many emerging economies. 2 We are seeing signs of recovery. Thanks to the development and rollout of vaccines and massive public spending to stimulate demand, there are signs that the situation is being brought under control so that we can live with the virus more like we do with normal flus. -

Canadian Foreign Policy? Do You Think This Reform Would Be Politically “Difficult” Or “Easy”? How/Why?

POLI 3569 ONLINE-ONLY VERSION, WINTER 2021 Professor Brian Bow ([email protected]) UPDATED JANUARY 10 The purpose of this course is to provide a basic overview of Canada’s political and diplomatic relations with the rest of the world. There will be some attention to specific policy questions here and there, but most of the course is organized around “bigger” debates about how to think about how Canada fits into the world, what it can and should try to accomplish, and who gets to make those choices. The first part of the course—Module 1, below—lays out the conventional history of Canada’s foreign relations, emphasizing the way that past developments shape current and future decisions. Module 2 looks at a variety of different critiques of this conventional view (realist, neomarxist, feminist, postcolonial, etc.), to try to give you a sense of the main theoretical debates. Module 3 shifts the focus to the political structures of foreign policy decision-making in Canada (e.g., parliament, bureaucracy, provinces, etc.). And Module 4 wraps things up by connecting the previous debates to some difficult foreign policy choices facing Canada today (e.g., relations with China, climate change, trade, arms exports, etc.). Basic format of the course As with almost all Dalhousie courses this year, POLI 3569 for Winter 2021 is going to be online only. Most parts of the course are asynchronous (i.e., students engage with the course material on their own time, within weekly sections); however, unlike some other courses, POLI 3569 provides a choice between synchronous and asynchronous options for some course components. -

2016-2017 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2016-17 Contents About the School 3 Highlights of the Year 4 Research Clusters 6 Outreach & Events 7 Board of Directors 16 BSIA People 18 PhD Students 22 Masters Students 24 Policy Briefs - Global Affairs Canada 25 PhD Graduates 26 Masters Graduates 27 Faculty Books and Publications 28 2 About the School The Balsillie School of International Affairs (BSIA) is an institute for advanced research, programs, while CIGI, as a think tank, uses its in-house expertise and its worldwide education, and outreach in the fields of global governance and international public network of practitioners to help inform and guide BSIA’s outreach and collaborative policy. research. The BSIA is also the home to three research centres with an international profile - the Academic Council on the United Nations System (ACUNS), the As a hub in a global network of scholars, practitioners and students, BSIA aims to International Migration Research Centre (IMRC) and the Centre for Sustainable Food develop new solutions to humanity’s critical problems, improve global governance Systems. now and in the future, and enhance the quality of people’s lives around the world. The unique integration of the collaborating institutions’ approaches and cultures gives Founded in 2007 by philanthropist Jim Balsillie, BSIA is an equal collaboration among BSIA an unmatched ability to promote vigorous engagement across boundaries the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), the University of Waterloo of discipline and practice, to connect today’s experts with tomorrow’s leaders in (UW), and Wilfrid Laurier University (Laurier). The collaborating institutions bring critical debate and analysis, and to achieve—in all its work—the highest standards of to BSIA different but complementary strengths, so they have different roles and excellence. -

Market Indicators As at End*: August-2020

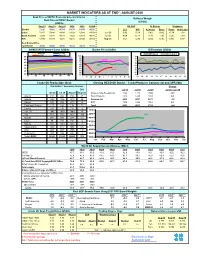

MARKET INDICATORS AS AT END*: AUGUST-2020 Spot Price of OPEC Basket & Selected Crudes Refiners' Margin Real Price of OPEC Basket (US$/b) (US$/b) Aug-18 Aug-19 Aug-20 2018 2019 2020# US Gulf N. Europe Singapore Basket 72.26 59.62 45.19 69.78 64.04 40.50 LLS WTI A. Heavy Brent Oman Arab Light Dubai 72.47 58.88 43.89 69.68 63.48 41.54 Jun-20 3.92 5.19 0.42 0.42 -0.74 1.02 North Sea Dtd 72.64 58.83 44.79 71.22 64.19 40.88 Jul-20 4.64 6.13 -1.86 1.30 1.26 1.99 WTI 67.99 54.84 42.36 65.16 57.02 38.15 Aug-20 3.67 5.30 -2.05 0.16 0.86 0.87 Real Basket Price Jun01=100 46.86 39.02 28.30 35.22 44.73 26.19 NYMEX WTI Forward Curve (US$/b) Basket Price (US$/b) Differentials (US$/b) May-20 Jun-20 WTI-Brent Brent-Dubai Jul-20 Aug-20 50 100 3 90 2 45 2018 80 1 70 40 0 60 35 2019 -1 50 30 40 -2 2020 -3 25 30 20 -4 20 10 -5 1M 3M 5M 7M 9M 11M J F M A M J J A S O N D 03 05 07 11 13 17 19 21 25 27 31 Crude Oil Production (tb/d) Closing OECD Oil Stocks - Crude/Products Commercial and SPR (Mb) Crude Oil Production (Tb/d) Production: Secondary Sources Change Diff. -

The Impact of the Decline in Oil Prices on the Economics, Politics and Oil Industry of Venezuela

THE IMPACT OF THE DECLINE IN OIL PRICES ON THE ECONOMICS, POLITICS AND OIL INDUSTRY OF VENEZUELA By Francisco Monaldi SEPTEMBER 2015 B | CHAPTER NAME ABOUT THE CENTER ON GLOBAL ENERGY POLICY The Center on Global Energy Policy provides independent, balanced, data-driven analysis to help policymakers navigate the complex world of energy. We approach energy as an economic, security, and environmental concern. And we draw on the resources of a world-class institution, faculty with real-world experience, and a location in the world’s finance and media capital. Visit us atenergypolicy. columbia.edu facebook.com/ColumbiaUEnergy twitter.com/ColumbiaUEnergy ABOUT THE SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS SIPA’s mission is to empower people to serve the global public interest. Our goal is to foster economic growth, sustainable development, social progress, and democratic governance by educating public policy professionals, producing policy-related research, and conveying the results to the world. Based in New York City, with a student body that is 50 percent international and educational partners in cities around the world, SIPA is the most global of public policy schools. For more information, please visit www.sipa.columbia.edu THE IMPACT OF THE DECLINE IN OIL PRICES ON THE ECONOMICS, POLITICS AND OIL INDUSTRY OF VENEZUELA By Francisco Monaldi* SEPTEMBER 2015 *Francisco Monaldi is Baker Institute Fellow in Latin American Energy Policy and Adjunct Professor of Energy Economics at Rice University, Belfer Center Associate in Geopolitics of Energy at the Harvard Kennedy School, Professor at the Instituto de Estudios Superiores de Administracion (IESA) in Caracas, Venezuela, and Founding Director of IESA’s Center on Energy and the Environment. -

Global Dynamics of Oil Price Fluctuations

RUCHAN KAYA MESUT HAKKI CASIN 146146 147 CASPIAN REPORT, SPRING 2015 GLOBAL DYNAMICS OF OIL PRICE FLUCTUATIONS RUCHAN KAYA SENIOR RESARCH FELLOW, ENERGY AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS EXPERT, HASEN The crude oil saw the lowest price levels since 2009 and has a few economic and political reasons behind the drop. The dramatic increase in the supply side is one of the main factors. Within the past year or so, only one around $55-60 levels and are cur- thing is certain about the oil prices rently hovering around $65. Look- and that is the uncertainty of the fu- ing at these numbers and future es- ture price levels. In June 2014, the timates, clearly, we cannot predict end of the year price predictions of the price of oil perfectly, but we can Barclay’s was $109 per barrel. How- identify the reasons of current trend ever, by that time, in January, the of decline, therefore lowering the MESUT HAKKI CASIN price was around $50 per barrel. amount of uncertainty in future esti- In early 2015 Goldman Sachs and mations and policy behavior. 146 147 Bank of America Merrill Lynch made even more worrisome price esti- CASPIAN REPORT, SPRING 2015 mates down around $35-45 range is that it is important to be aware of Onethe fact of the that first history things of oilto alreadyrecognize in- early March, the oil prices oscillated cludes such price booms and busts. in their Q1 projections. However, in Figure 1. Crude Oil Prices in 1861-2013 ($) Source: BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2014 As Figure 1 shows, recent low prices than doubled the crude oil price, ris- of oil are nothing new as sharp de- ing from $14 per barrel to over $30 clines have existed in the past.