Dp -O7f^3D PER CURIAM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gavin Newsom Governor of California

GAVIN NEWSOM GOVERNOR OF CALIFORNIA Life in Brief Quick Summary Born: October 10, 1967 Progressive politician who has established a reputation of advocating for marginalized Hometown: San Francisco, CA groups such as racial minorities and the LGBT community through unorthodox means. Current Residence: Greenbrae, CA Effectively leveraged family connections to jumpstart career Religion: Catholic • Embraces forging his own path on progressive issues; publicly goes against the status quo Education: • Fights for what he believes is right through • BS, Political Science, Santa Clara University, unconventional means; as Mayor of San 1989 Francisco, broke the state law to support same- sex marriage, putting his reputation at risk with Family: the broader Democratic Party • Wife, Jennifer Siebel, documentary filmmaker • Shifted from the private sector to politics after and actress working for Willie Brown • Divorced, Kimberly Guilfoyle, political analyst • Working for Jerry Brown allowed him to learn and former Fox News commentator tools of the trade and become his successor • Four children • Well connected to CA political and philanthropic elites; Speaker Nancy Pelosi is his aunt and Work History: political mentor, and he is friends with Sen. • Governor of California, 2019-present Kamala Harris and the Getty family • Lt. Governor of California, 2011-2019 • Advocates for constituents to engage with their • Mayor of San Francisco, 2004-2011 government, using technology to participate • Member of the San Francisco Board of nd Supervisors from the -

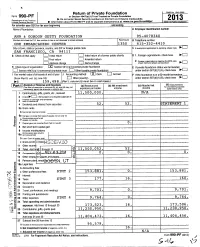

Return of Private Foundation

s III, OMB No 1545-0052 0, Return of Private Foundation Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Treasury Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. 2013 Department of the ► InterAal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.,rs.gov/form9!9Opf. en o u is ns ec ion For calendar year 2013 or tax year beginning and ending Name of foundation A Employer Identification number ANN & Gn RT)ON aRTTY FOUNDATION 95-4078340 Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ONE EMBARCADERO CENTER 1350 415-352-441 0 City or town , state or province , country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending , check here ► SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94111 G Check all that apply Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations , check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, ► O Address chan g e Name chan g e check here and attach computation H Check type of organization OX Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a )( 1 nonexem pt charitable trust = Other taxable p rivate foundati on under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► ^ I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method Cash L_J Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part ll, col. -

William Newsom POLITICS, LAW, and HUMAN RIGHTS

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California William Newsom POLITICS, LAW, AND HUMAN RIGHTS Interviews conducted by Martin Meeker in 2008-2009 Copyright © 2009 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and William Newsom, dated August 7, 2009, and Barbara Newsom, dated September 22, 2009 (by her executor), and Brennan Newsom, dated November 12, 2009. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Symphonic III: Getty & Berlioz Program Notes & Translations

Symphonic III: Getty & Berlioz Thurs, Feb 1, 2018 at 8p - Zellerbach Hall, Berkeley Fri, Feb 2, 2018 at 8p - Hume Hall, San Francisco Conservatory of Music http://www.berkeleysymphony.org/concerts/getty-berlioz/ Program Fauré: Cantique de Jean Racine Gordon Getty: Joan and the Bells Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique Conductor & Artists Keitaro Harada, guest conductor Lisa Delan, soprano Lester Lynch, baritone Eric Choate, concertmaster Berkeley Symphony and Chorus Program Notes & Translations Gabriel Fauré Born May 12, 1845, in Pamieres, France; died November 4, 1924, in Paris Cantique de Jean Racine, Op. 11 Composed: 1864-65 First performance: August 4, 1866, in Montivilliers, France Duration: approximately 7 minutes Scored for mixed choir and pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, and horns, plus harp and strings In sum: ● Gabriel Fauré’s best-loved work is his setting of the Requiem, but he was already hiding his sensitive, balanced choral style in Cantique de Jean Racine, an early student work. ● Written for a composition competition when he was 19, Cantique is a brief, beautifully proportioned setting of three stanzas based on a liturgical prayer. Born in the south of France, Gabriel Fauré was a bit of an anomaly in his family — the only one among his five siblings with musical leanings. But these were already evident by an early age, so that Fauré was sent off to Paris at the age of nine to concentrate on his musical studies at the École Niedermeyer, a college that specialized in preparing for careers in religious music. Camille Saint-Saëns became an important mentor, and young Fauré was educated as a choirmaster and organist. -

Curated by Nico Muhly Soundbox

FOCUS CURATED BY NICO MUHLY SOUNDBOX 1 “The theme of this SoundBox is Focus, a notion I’m trying to explore in various senses of the word.” —Nico Muhly 2 Esa-Pekka Salonen SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY MUSIC DIRECTOR San Francisco Symphony Music Director Esa-Pekka Salonen has, through his many high-profile conducting roles and work as a leading composer, shaped a unique vision for the present and future of the contemporary symphony orchestra. Salonen recently concluded his tenure as Principal Conductor & Artistic Advisor for London’s Philharmonia Orchestra and he is Artist in Association at the Finnish National Opera and Ballet. He is a member of the faculty of the Colburn School in Los Angeles, where he developed and directs the pre-professional Negaunee Conducting Program. Salonen is the Conductor Laureate for both the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Los Angeles Philharmonic, where he was Music Director from 1992 until 2009. Salonen co-founded— and from 2003 until 2018 served as the Artistic Director for—the annual Baltic Sea Festival. 3 The Orchestra Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director SECOND VIOLINS CELLOS Michael Tilson Thomas, Music Director Laureate Dan Carlson, Principal Vacant, Principal Herbert Blomstedt, Conductor Laureate Dinner & Swig Families Chair Philip S. Boone Chair Daniel Stewart, San Francisco Symphony Youth Helen Kim, Associate Principal Peter Wyrick, Associate Principal Orchestra Wattis Foundation Music Director Audrey Avis Aasen-Hull Chair Peter & Jacqueline Hoefer Chair Ragnar Bohlin, Chorus Director Jessie Fellows, Assistant Principal Amos Yang, Assistant Principal Vance George, Chorus Director Emeritus Vacant Vacant The Eucalyptus Foundation Second Century Chair Lyman & Carol Casey Second Century Chair FIRST VIOLINS Raushan Akhmedyarova Barbara Andres Alexander Barantschik, Concertmaster David Chernyavsky The Stanley S. -

Haute 100 All.Pdf

SPECIAL FEATURE 2016 HAUT E THE MVPS IN TECHNOLOGY, VENTURE CAPITAL, ARTS, FOOD & WINE, BANKING, REAL ESTATE, PHILANTHROPY & SPORTS HERE IS OUR 2016 LIST OF THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA’S MOST A-LIST 2014 S.F. GIANTS, STEPHEN CURRY PHOTO: GOLDEN WARRIORS, STATE JOE LACOB PHOTO: SABIN ORR, JED YORK PHOTO: COURTESY SAN FRANCISCO 49ERS BILLIONAIRES, PHILANTHROPISTS, POWER COUPLES, ENTREPRENEURS, © ATHLETES AND, OF COURSE, TECH TITANS. THIS IS THE HOME OF SILICON VALLEY, AFTER ALL. BRUCE BOCHY PHOTO: 46 ww CATEGORY: POWER COUPLES FEATURE SPECIAL PAM AND LARRY BAER ROBIN AND MICHELLE BAGGETT SLOAN AND ROGER BARNETT WHAT MAKES THEM HAUTE WHAT MAKES THEM HAUTE WHAT MAKES THEM HAUTE Larry Baer, president and CEO of the San Francisco Robin Baggett, a former general counsel for the Roger and Sloan Barnett were once prominent Giants, possesses a reputation as one of professional Golden State Warriors, and his marketing whiz figures on the young New York social scene; now, - sports’ leading visionaries—not to mention World wife, Michelle Baggett, revolutionized the wine this eco-conscious couple plays a similar role Series rings for 2010, 2012 and 2014. His wife, Pam, industry 10 years ago when they started Alpha in San Francisco. In 2004, Roger, a former Wall founded For Goodness Sake, an e-commerce site and Omega, in Napa Valley’s Rutherford district, based Street financier, paid $310 million for Shaklee pop-up boutique that donates 25 percent of proceeds on an 80 percent direct-to-consumer business Corporation. He’s the chairman and CEO of the from every purchase to charity partners. -

Could the City's Westside Burn After an Earthquake?

Glenn Rogers Quentin Kopp Taraval Station Report Is the Business Model at Uber and Lyft in Even Donald “Bone Spur” gets Quentin’s Get the low-down on crime straight from jeopardy? .......................................... 2 goat around the 4th of July ..................3 the Captain on the frontline ................10 Geoge Wooding Central Council Wildflowers Mayor Breed reminds George that the A Special Message from Outgoing If flowers are the “earth’s way of laughing” Willie era may not be over ..............5 Mayor Farrell and a Crime update ..... 3 and we need some of that .................... 9 Volume 31 • Number 6 Celebrating Our 31st Year www.westsideobserver.com July/August 2018 No Takers Yet: Laguna Honda’s Aid-In-Dying Program by Dr. Derek Kerr & Dr. Maria Rivero s reported in the June 2017 Westside Observer (WSO), Laguna Honda Hospital (LHH) Aapproved a medical aid-in-dying policy last May. Based on California’s 2016 End of Life Options Act, it allows terminally ill patients with decision-making capacity to self-administer prescribed lethal sedatives in the hospital. While awaiting LHH’s promised annual report on its aid-in-dying program, the WSO requested records showing the number of lethal prescriptions issued and the number of associated deaths. LHH’s response: “zero” and “zero”. Zero takers may seem surprising in a hospital that reported 181 deaths in 2017. However, few dying patients choose this option. For example, Oregon’s 20 year old “Death with Dignity” program accounted for just 144 deaths in 2017. Despite a steady rise in par- ticipants, that’s merely 0.4% of Oregon deaths. -

Spotlight on Arts Grantmaking in California

The Foundation Center–San Francisco OCTOBER 2006 SPOTLIGHT ON ARTS GRANTMAKING IN CALIFORNIA The Foundation Center’s mission is to strengthen the nonprofit TYPES OF SUPPORT sector by advancing knowledge about U.S. philanthropy. We are pleased to present this brief exploration into arts and culture Among those specified, program support and capital support grantmaking (referred to as “arts” throughout the report). We were the most common types of support in California arts hope this look at California grantmakers and recipients and grantmaking. (Figure 2) Within the area of capital support, those foundations outside California that support the state’s building/renovation and capital campaigns represent nearly arts organizations will help you gain insights into the state of 19% of grant dollars, followed by close to 8% for endowments, arts grantmaking in California. The report includes statistical and nearly 2% for collections acquisition. charts and tables based on the Center’s annual grants sample, a mini-directory of significant arts funders in California, Performing Arts and Museums captured the largest share and profiles of select California foundations that support of California giving to the arts individual artists. CALIFORNIA GRANTS SAMPLE Each year the Foundation Center indexes all of the grants of $10,000 and up awarded by approximately 1,000 of the nation’s largest foundations. Our most recent (2004) sample includes over 126,000 grants awarded by 1,172 U.S. foundations totaling $15.5 billion. Of the sampled foundations, 119 were based in California. The charts on the right are based on the 95 California foundations that made arts-related grants to California-based Source: The Foundation Center recipients and were included in the 2004 sample. -

Extensions of Remarks E1698 HON. LAMAR SMITH HON. NANCY PELOSI

E1698 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks December 20, 2018 Ceres Police Department. He was sworn into CELEBRATING THE LIFE OF BILL Depression-era San Francisco on February the Sheriff’s Office in January of 1996, where NEWSOM 15, 1934 and raised on Jefferson St. at Baker, in the shadow of the Palace of Fine Arts. He he has served ever since. As Deputy Sheriff was the second and last surviving of six chil- he filled an impressive variety of roles as Pa- HON. NANCY PELOSI dren (Carole A. Onorato, Belinda B. (‘‘Bar- trol, K9 Handler and Supervisor, Bailiff, Field OF CALIFORNIA bara’’) Newsom, Brennan J. Newsom, Sharon Training Officer and Detective. As Sergeant he IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES C. Mohun, Patrick J. Newsom) born to Wil- was assigned to Patrol and supervised the liam A. Newsom, Jr. and Christine Newsom. Wednesday, December 19, 2018 Bill’s parents were Mission District Irish. High Tech Crimes Unit. As Lieutenant he Ms. PELOSI. Mr. Speaker, I include the fol- His father, William A. Newsom, Jr., (b. 1902) worked in Homeland Security, Internal Affairs, lowing obituary from the San Francisco Chron- was a developer and civic leader who sur- and was the Northwest Area Commander. vived the 1906 earthquake and was closely as- icle honoring Bill Newsom: sociated with the late Gov. Edmund G. Sheriff Christianson has been a mainstay of Justice William A. (‘‘Bill’’) Newsom, pater- (‘‘Pat’’) Brown. Bill’s paternal grandfather, the community throughout his time in office. familias of a pioneering San Francisco fam- also William A. Newsom, born in San Fran- Public Safety facilities have been expanded ily and a revered figure to his children, cisco in 1865, was a contractor and early city grandchildren and expansive clan, ardent de- with more jail beds, a medical and mental father who later became an associate of A.P. -

Item 3A. LBR-2017-18-045 Balboa Cafe.Pdf

CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO LONDON N. BREED, MAYOR OFFICE OF SMALL BUSINESS REGINA DICK-ENDRIZZI, DIRECTOR Legacy Business Registry Staff Report HEARING DATE AUGUST 13, 2018 BALBOA CAFE Application No.: LBR-2017-18-045 Business Name: Balboa Cafe Business Address: 3199 Fillmore Street District: District 2 Applicant: Jeremy Scherer, President Nomination Date: June 5, 2018 Nominated By: Supervisor Catherine Stefani Staff Contact: Richard Kurylo [email protected] BUSINESS DESCRIPTION Balboa Cafe (“the Balboa”) opened in 1913 despite the original signage above the door that says 1914 (the owner was superstitious about the number 13). The restaurant and bar has been operating continuously for 105 years in the Cow Hollow neighborhood. The Balboa was originally a working-man’s saloon with a sawdust floor, pool tables, and a carving station serving sandwiches in the corner. Balboa Cafe has become a more sophisticated establishment over the years, but the historical integrity of the building is intact. Many original details remain, such as the back bar, the exterior signage that announces Off Sale Liquors, the original Coca-Cola sign, the windows, transoms and small details throughout the restaurant’s interior. There is little information about the Balboa Cafe owners and its history from the time of its opening through the early 1970s when Jack Hobday (aka Jack Slick, brother of Henry Africa aka Norman Hobday) took over operations. In 1980, famed chef Jeremiah Tower came on as Executive Chef for four years, helping to establish a proper bar menu. In 1994, Gavin Newsom’s PlumpJack Group’s Balboa Cafe Partners acquired the Balboa and debuted with minimal updates in 1995. -

Plump Jack, Opera by Gordon Getty

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PLUMP JACK – GORDON GETTY’S OPERA INSPIRED BY SHAKESPEARE’S IMMORTAL ROGUE “SWEET JACK FALSTAFF” HYBRID MULTI-CHANNEL SACD RELEASED ON THE PENTATONE CLASSICS LABEL “Falstaff is all the world,” declares Gordon Getty about the title character of his opera, Plump Jack, which has been released in concert version on the PentaTone Classics label (PTC 5186 445, hybrid multi-channel SACD). “We must meet him at the top of his game: outwitting his arresters, winning the crowd, pulling the Chief Justice’s beard and borrowing another ten pounds for good measure. His next scene at Gad’s Hill is the endearing opposite. Here Falstaff is flustered, flummoxed and apoplectic as Hal and Boy play their tricks on him…It is at Gad’s Hill that we love Falstaff most. 2 “Love him we must,” Mr. Getty continues, “since all who know him do. He is mourned in the end as much as Hamlet or Brutus or Lear. ‘Falstaff, he is dead,’ says Pistol, ‘and we must yearn therefore.’ ‘He’s in Arthur’s bosom,’ says Hostess, even though she never saw a farthing back from him. Bardolph adds the most beautiful tribute of all: ‘Would I were with him, wheresome’er he is, either in heaven or in hell.’” Plump Jack features conductor Ulf Schirmer, 10 vocal soloists, the Munich Radio Orchestra and the Bavarian Radio Choir in a work that the composer has been developing over three decades, focusing upon the character of Falstaff from Shakespeare’s history plays, Henry IV Parts 1 and 2 and Henry V. -

Mavambo Engoma, Rooted in Music Curated by Chinyakare Ensemble

MAVAMBO ENGOMA, ROOTED IN MUSIC CURATED BY CHINYAKARE ENSEMBLE 1 Julia and Kanukai Chigamba of Chinyakare Ensemble on Mavambo eNgoma, Rooted in Music “Music is the roots, and it’s the family, “Music is a universal language that it’s the community, it’s the world.” helps everyone, if everyone explores —Julia Chigamba it with respect. And love.” —Kanukai Chigamba 2 Esa-Pekka Salonen SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY MUSIC DIRECTOR San Francisco Symphony Music Director Esa-Pekka Salonen has, through his many high-profile conducting roles and work as a leading composer, shaped a unique vision for the present and future of the contemporary symphony orchestra. Salonen is currently the Principal Conductor & Artistic Advisor for London’s Philharmonia Orchestra and is Artist in Association at the Finnish National Opera and Ballet. He is a member of the faculty of the Colburn School in Los Angeles, where he developed and directs the pre-professional Negaunee Conducting Program. Salonen is the Conductor Laureate for both the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Los Angeles Philharmonic, where he was Music Director from 1992 until 2009. Salonen co-founded— and from 2003 until 2018 served as the Artistic Director for—the annual Baltic Sea Festival. 3 The Orchestra Esa-Pekka Salonen, Music Director SECOND VIOLINS CELLOS Michael Tilson Thomas, Music Director Laureate Dan Carlson, Principal Vacant, Principal Herbert Blomstedt, Conductor Laureate Dinner & Swig Families Chair Philip S. Boone Chair Daniel Stewart, San Francisco Symphony Youth Helen Kim, Associate Principal Peter Wyrick, Associate Principal Orchestra Wattis Foundation Music Director Audrey Avis Aasen-Hull Chair Peter & Jacqueline Hoefer Chair Ragnar Bohlin, Chorus Director Jessie Fellows, Assistant Principal Amos Yang, Assistant Principal Vance George, Chorus Director Emeritus Vacant Vacant The Eucalyptus Foundation Second Century Chair Lyman & Carol Casey Second Century Chair FIRST VIOLINS Raushan Akhmedyarova Barbara Andres Alexander Barantschik, Concertmaster David Chernyavsky The Stanley S.