John M. Anderson Oral History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas--Artur Schnabel (1932-1935) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by James Irsay (Guest Post)*

The Complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas--Artur Schnabel (1932-1935) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by James Irsay (guest post)* Artur Schnabel Austrian pianist Artur Schnabel has been called “the man who invented Beethoven”... a strange thing to say considering Schnabel was born more than half a century after Beethoven, universally recognized as the greatest composer in Europe, died in 1827. What, then, did Artur Schnabel invent? The 32 piano sonatas of Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) represent one of the great artistic achievements in human history, and stand as the musical autobiography of the great composer's maturity, from his 25th until his 53rd year, four years before his death. The fruit of those years mark a staggering creative journey that began and ended in the composer's adopted home of Vienna, “Music Central” to the German-speaking world. Beethoven's musical path led from the domain of Haydn and Mozart to the world of his late period, when the agonizing progress of his deafness had become complete. By then, Beethoven's musical narrative had begun to speak a new language, proceeding according to a new logic that left many listeners behind. While the beauties of his music and his deep genius were generally recognized, at the same time, it was thought by some critics that Beethoven frequently smudged things up with his overly- bold, unfettered invention, even well before his final period: Beethoven, who is often bizarre and baroque, takes at times the majestic flight of an eagle, and then creeps in rocky pathways. He first fills the soul with sweet melancholy, and then shatters it by a mass of shattered chords. -

Rachmaninoff's Rhapsody on a Theme By

RACHMANINOFF’S RHAPSODY ON A THEME BY PAGANINI, OP. 43: ANALYSIS AND DISCOURSE Heejung Kang, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2004 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor and Program Coordinator Stephen Slottow, Minor Professor Josef Banowetz, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Interim Chair of Piano Jessie Eschbach, Chair of Keyboard Studies James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrill, Interim Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kang, Heejung, Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43: Analysis and Discourse. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2004, 169 pp., 40 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 39 titles. This dissertation on Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43 is divided into four parts: 1) historical background and the state of the sources, 2) analysis, 3) semantic issues related to analysis (discourse), and 4) performance and analysis. The analytical study, which constitutes the main body of this research, demonstrates how Rachmaninoff organically produces the variations in relation to the theme, designs the large-scale tonal and formal organization, and unifies the theme and variations as a whole. The selected analytical approach is linear in orientation - that is, Schenkerian. In the course of the analysis, close attention is paid to motivic detail; the analytical chapter carefully examines how the tonal structure and motivic elements in the theme are transformed, repeated, concealed, and expanded throughout the variations. As documented by a study of the manuscripts, the analysis also facilitates insight into the genesis and structure of the Rhapsody. -

Gavin Newsom Governor of California

GAVIN NEWSOM GOVERNOR OF CALIFORNIA Life in Brief Quick Summary Born: October 10, 1967 Progressive politician who has established a reputation of advocating for marginalized Hometown: San Francisco, CA groups such as racial minorities and the LGBT community through unorthodox means. Current Residence: Greenbrae, CA Effectively leveraged family connections to jumpstart career Religion: Catholic • Embraces forging his own path on progressive issues; publicly goes against the status quo Education: • Fights for what he believes is right through • BS, Political Science, Santa Clara University, unconventional means; as Mayor of San 1989 Francisco, broke the state law to support same- sex marriage, putting his reputation at risk with Family: the broader Democratic Party • Wife, Jennifer Siebel, documentary filmmaker • Shifted from the private sector to politics after and actress working for Willie Brown • Divorced, Kimberly Guilfoyle, political analyst • Working for Jerry Brown allowed him to learn and former Fox News commentator tools of the trade and become his successor • Four children • Well connected to CA political and philanthropic elites; Speaker Nancy Pelosi is his aunt and Work History: political mentor, and he is friends with Sen. • Governor of California, 2019-present Kamala Harris and the Getty family • Lt. Governor of California, 2011-2019 • Advocates for constituents to engage with their • Mayor of San Francisco, 2004-2011 government, using technology to participate • Member of the San Francisco Board of nd Supervisors from the -

~Tate of M:Enne~~Ee

~tate of m:enne~~ee HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION NO. 695 By Representative Shepard and Senators Crowe, Herron A RESOLUTION to honor the professional achievements of musician John Rich. WHEREAS, it is fitting that the members of this body should pause to honor those exemplary citizens who contribute significantly to the reputation of Tennessee throughout the world as the center of the music industry universe and home of the most generous and compassionate citizenry by helping to reinforce the "Volunteer State" nickname; and WHEREAS, one such citizen is John Rich who has garnered high acclaim as a singer, songwriter, record producer, and television personality over the course of his illustrious and storied career in the music and entertainment industry; and WHEREAS, Mr. Rich, born on January 7, 1974, in Amarillo, Texas, moved to middle Tennessee in the early 1990s, where he attended and graduated from Dickson County Senior High School with the class of 1992, making lifelong friends and ties with the community; and WHEREAS, after high school, Mr. Rich chose to forego college to pursue his dream of becoming a country music recording artist. In the summer of 1992, he was chosen by executives at Opryland USA to be a performer in the Nashville-based theme park's daily variety show entitled "Country Music USA," wherein Mr. Rich performed songs by country music superstars such as George Jones, Garth Brooks, George Strait, and Vince Gill; and WHEREAS, during his time at Opryland USA, Mr. Rich met fellow performer Dean Sams, who along with Mr. Rich and two other fellow Texans formed a band named Texassee. -

2017-2018 Master Class-Leon Fleisher

Welcome to the 2017-2018 season. The talented students and extraordinary faculty of the Lynn LEON FLEISHER MASTER CLASS Conservatory of Music take this opportunity to share with you the beautiful world of music. Your Wednesday, January 24, 2018 at 7:00 pm ongoing support ensures our place among the premier conservatories Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall of the world and a staple of our community. - Jon Robertson, dean PROGRAM There are a number of ways by which you can help us fulfill our mission: Friends of the Conservatory of Music Sonata Op. 2 No. 2 in A Major Ludwig van Beethoven Lynn University’s Friends of the Conservatory of Music is a IV Rondo: Grazioso (1770-1827) volunteer organization that supports high-quality music education through fundraising and community outreach. Raising more than $2 million since 2003, the Friends support Lynn’s effort to provide Chance Israel, piano free tuition scholarships and room and board to all Conservatory of Music students. The group also raises money for the Dean’s Discretionary Fund, which supports the immediate needs of the university’s music performance students. This is accomplished through annual gifts and special events, such as outreach concerts and the annual Gingerbread Holiday Concert. To learn more about joining the Friends and its many benefits, Scherzo No. 4 in E Major Frederic Chopin such as complimentary concert admission, visit Give.lynn.edu/support-music. (1810-1849) The Leadership Society of Lynn University Meiyu Wu, piano The Leadership Society is the premier annual giving society for donors who are committed to ensuring a standard of excellence at Lynn for all students. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

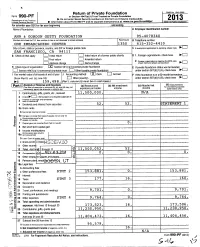

Return of Private Foundation

s III, OMB No 1545-0052 0, Return of Private Foundation Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Treasury Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. 2013 Department of the ► InterAal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.,rs.gov/form9!9Opf. en o u is ns ec ion For calendar year 2013 or tax year beginning and ending Name of foundation A Employer Identification number ANN & Gn RT)ON aRTTY FOUNDATION 95-4078340 Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ONE EMBARCADERO CENTER 1350 415-352-441 0 City or town , state or province , country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending , check here ► SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94111 G Check all that apply Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations , check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, ► O Address chan g e Name chan g e check here and attach computation H Check type of organization OX Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a )( 1 nonexem pt charitable trust = Other taxable p rivate foundati on under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► ^ I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method Cash L_J Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part ll, col. -

William Newsom POLITICS, LAW, and HUMAN RIGHTS

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California William Newsom POLITICS, LAW, AND HUMAN RIGHTS Interviews conducted by Martin Meeker in 2008-2009 Copyright © 2009 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and William Newsom, dated August 7, 2009, and Barbara Newsom, dated September 22, 2009 (by her executor), and Brennan Newsom, dated November 12, 2009. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Riccardo Muti Conductor Rudolf Buchbinder Piano Wagner Siegfried’S Rhine Journey and Funeral March from Götterdämmerung Beethoven Piano Concerto No

Please note that pianist Leif Ove Andsnes has withdrawn from these concerts. The CSO welcomes Rudolf Buchbinder, who has graciously agreed to perform. The program remains unchanged. PROGRAM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-SECOND SEASON Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Music Director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, June 13, 2013, at 8:00 Friday, June 14, 2013, at 1:30 Saturday, June 15, 2013, at 8:00 Riccardo Muti Conductor Rudolf Buchbinder Piano Wagner Siegfried’s Rhine Journey and Funeral March FROM Götterdämmerung Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Major, Op. 58 Allegro moderato Andante con moto— Rondo: Vivace RUDOLF BUCHBINDER INTERMISSION Bruckner Symphony No. 1 in C Minor Allegro Adagio—Andante Scherzo: Lively Finale: Agitated and fiery These performances have been enabled by the Juli Grainger Fund. Support of the music director and related programs is made possible in part by a generous gift from the Zell Family Foundation. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. COMMENTS BY PHILLIP HUSCHER Richard Wagner Born May 22, 1813, Leipzig, Germany. Died February 13, 1883, Venice, Italy. Siegfried’s Rhine Journey and Funeral March FROM Götterdämmerung iegfried’s Death was the original then e Young Siegfried, and finally Stitle of the prose sketch for an e Valkyrie each demanded yet opera that grew, over the span of another opera before it to provide twenty-eight years, into the most background and to set all the nec- monumental undertaking in the essary narrative strands in motion. -

RCA LHMV 1 His Master's Voice 10 Inch Series

RCA Discography Part 33 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA LHMV 1 His Master’s Voice 10 Inch Series Another early 1950’s series using the label called “His Master’s Voice” which was the famous Victor trademark of the dog “Nipper” listening to his master’s voice. The label was retired in the mid 50’s. LHMV 1 – Stravinsky The Rite of Spring – Igor Markevitch and the Philharmonia Orchestra [1954] LHMV 2 – Vivaldi Concerto for Oboe and String Orchestra F. VII in F Major/Corelli Concerto grosso Op. 6 No. 4 D Major/Clementi Symphony Op. 18 No. 2 – Renato Zanfini, Renato Fasano and Virtuosi di Roma [195?] LHMV 3 – Violin Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 2 (Bartok) – Yehudi Menuhin, Wilhelm Furtwangler and the Philharmonia Orchestra [1954] LHMV 4 – Beethoven Concerto No. 5 in E Flat Op. 73 Emperor – Edwin Fischer, Wilhelm Furtwangler and the Philharmonia Orchestra [1954] LHMV 5 – Brahms Concerto in D Op. 77 – Gioconda de Vito, Rudolf Schwarz and the Philharmonia Orchestra [1954] LHMV 6 - Schone Mullerin Op. 25 The Maid of the Mill (Schubert) – Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Gerald Moore [1/55] LHMV 7 – Elgar Enigma Variations Op. 36 Wand of Youth Suite No. 1 Op. 1a – Sir Adrian Boult and the London Philharmonic Orchestra [1955] LHMV 8 – Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F/Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D – Harold Jackson, Gareth Morris, Herbert Sutcliffe, Manoug Panikan, Raymond Clark, Gerraint Jones, Edwin Fischer and the Philharmonia Orchestra [1955] LHMV 9 – Beethoven Symphony No. 5 in C Minor Op. -

Working Finding Aid the Center for Popular Music

THIS COLLECTION IS STILL IN PROCESS – WORKING FINDING AID THE CENTER FOR POPULAR MUSIC, MIDDLE TENNESSEE STATE UNIVERSITY, MURFREESBORO, TN ALAN L. MAYOR COLLECTION 17-005 Creator: Mayor, Alan Leslie (August 21, 1949 – February 22, 2015) Type of Material: Manuscript Materials, Photographs, Negatives, Slides, Datebooks, Sound Recordings Physical Description: 162 linear feet of manuscript material including: 113 linear feet of photographic prints 19 linear feet of negatives 22 linear feet of slides 5 linear feet of CD/DVD/Floppy disc photographic files 1 linear foot of datebooks 2 linear foot of press passes Dates: circa 1977 – 2012, bulk 1990-2000 Access/Restrictions: The collection is partially processed, but is open for research use. The Center for Popular Music only owns rights to the physical materials in this collection. All materials in this collection are under copyright that is owned by the Mayor Family. Researchers must receive prior written permission from the Mayor Family for any reproductions of use. Center staff are able to assist with copyright questions for this material. Provenance and Acquisition Information: This collection was donated by Alan Mayor’s sister, Theresa Mayor Smith, in October 2017. The Center’s Director and Archivist picked up a portion of the collection on October 6, 2017 from Mrs. Smith’s storage unit in Cadiz, Kentucky. The second, and largest, portion was picked up by the Center’s Archivist and Assistant Archivist on October 13, 2017 from Cadiz, Kentucky. The third batch of remanding binders of negatives was dropped off at the Center by Mrs. Smith on November 9, 2017. Subjects/Index Terms: Country music – 1971-1980 THIS COLLECTION IS STILL IN PROCESS – WORKING FINDING AID Alan L. -

Symphonic III: Getty & Berlioz Program Notes & Translations

Symphonic III: Getty & Berlioz Thurs, Feb 1, 2018 at 8p - Zellerbach Hall, Berkeley Fri, Feb 2, 2018 at 8p - Hume Hall, San Francisco Conservatory of Music http://www.berkeleysymphony.org/concerts/getty-berlioz/ Program Fauré: Cantique de Jean Racine Gordon Getty: Joan and the Bells Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique Conductor & Artists Keitaro Harada, guest conductor Lisa Delan, soprano Lester Lynch, baritone Eric Choate, concertmaster Berkeley Symphony and Chorus Program Notes & Translations Gabriel Fauré Born May 12, 1845, in Pamieres, France; died November 4, 1924, in Paris Cantique de Jean Racine, Op. 11 Composed: 1864-65 First performance: August 4, 1866, in Montivilliers, France Duration: approximately 7 minutes Scored for mixed choir and pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, and horns, plus harp and strings In sum: ● Gabriel Fauré’s best-loved work is his setting of the Requiem, but he was already hiding his sensitive, balanced choral style in Cantique de Jean Racine, an early student work. ● Written for a composition competition when he was 19, Cantique is a brief, beautifully proportioned setting of three stanzas based on a liturgical prayer. Born in the south of France, Gabriel Fauré was a bit of an anomaly in his family — the only one among his five siblings with musical leanings. But these were already evident by an early age, so that Fauré was sent off to Paris at the age of nine to concentrate on his musical studies at the École Niedermeyer, a college that specialized in preparing for careers in religious music. Camille Saint-Saëns became an important mentor, and young Fauré was educated as a choirmaster and organist.