UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Haunted Changes: How

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

Struggles of the Black Female Voice in Rap

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 2016 Stealing the Mic: Struggles of the Black Female Voice in Rap Miranda Flores Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Flores, Miranda, "Stealing the Mic: Struggles of the Black Female Voice in Rap" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 347. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/347 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stealing the Mic: Struggles of the Black Female Voice in Rap A Thesis Presented to The Honors Program of Butler University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Miranda R. Flores May 5, 2016 “You’ve taken my blues and gone-You sing ‘em on Broadway-And you sing ‘em in Hollywood Bowl- And you mixed ‘em up with symphonies-And you fixed ‘em-So they don’t sound like me. Yep, you done taken my blues and gone” -Langston Hughes From Langston Hughes to hip hop, African Americans have a long history of white appropriation. Rap, as a part of hip hop culture, gave rise to marginalized voices of minorities in the wake of declining employment opportunities and racism in the postindustrial economy beginning in the 1970s (T. Rose 1994, p. -

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

About the Artists

Contact: Michael Caprio, 702-658-6691 [email protected] Golden Slumbers is committed to creating projects that bring families together ABOUT THE ARTISTS MICHAEL MCDONALD This five-time Grammy winner is one of the most unmistakable voices in music, singing hits for three decades. His husky soulful baritone debuted 30 years ago, famously revitalizing the Doobie Brothers with "Takin' it to the Streets," "What a Fool Believes," and "Minute by Minute”. He went onto a distinguished solo career including duets with such R&B greats as James Ingram and Patti Labelle. Michael released the Grammy nominated Motown in 2003, selling over 1.3 million copies, followed by Motown 2, released in October 2004. PHIL COLLINS One of the music industry’s rock legends, Collins played drums, sang, wrote and arranged songs, played sessions, and helped Genesis become one of the leading lights in the Progressive rock field. After numerous solo hits and Platinum-selling albums, Walt Disney studios asked him in to compose the songs to their animated feature "Tarzan," and the sin- gle, "You'll be in my Heart," was a major hit which earned him the prestigious Academy, Grammy and Golden Globe Awards. He is currently working on three new Disney projects. With a new album in the pipeline, and a continued interest in all aspects of his past, Phil Collins has proved that there is no substitute for talent. SMOKEY ROBINSON Entering his fourth decade as a singer, songwriter and producer, this velvet-voiced crooner began his career as a founding Motown executive, and frontman for the Miracles. -

Mariella Cassar

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2014 Creative Responses to Maltese Culture and Identity: Case Study and Portfolio of Compositions Cassar, Mariella http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/3112 Plymouth University All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. CREATIVE RESPONSES TO MALTESE CULTURE AND IDENTITY: CASE STUDY AND PORTFOLIO OF COMPOSITIONS by MARIELLA CASSAR A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY University College Falmouth Incorporating Dartington College of Arts January 2014 MARIELLA CASSAR CREATIVE RESPONSES TO MALTESE CULTURE AND IDENTITY: CASE STUDY AND PORTFOLIO OF COMPOSITIONS Abstract The aim of this thesis is to explore the relationship between place, identity and musical practice. The study is inspired by Malta’s history and culture. This work presents a portfolio of seven musical compositions with a written component that highlights the historical and socio-cultural issues that had a bearing on the works presented. -

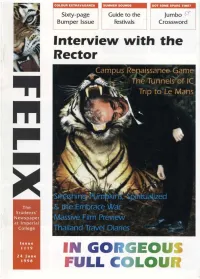

Felix Issue 1103, 1998

COLOUR EXTRAVAGANZA SUMMER SOUNDS GOT SOME SPARE TIME? Sixty-page Guide to the Jumbo $f Bumper Issue Festivals Crossword Interview with the Rector Campus Renaissance Game y the Tunnels "of IC 1 'I ^ Trip to Le Mans 7 ' W- & the Embrace War Massive Film Preview Thailand Travel Diaries IN GO EOUS FULL C 4 2 GAME 24 June 1998 24 June 1998 GAME 59 Automatic seating in Great Hall opens 1 9 18 unexpectedly during The Rector nicks your exam, killing fff parking space. Miss a go. Felix finds out that you bunged the builders to you're fc Rich old fo work Faster. "start small antiques shop. £2 million. Back one. ii : 1 1 John Foster electro- cutes himself while cutting IC Radio's JCR feed. Go »zzle all the Forward one. nove to the is. The End. P©r/-D®(aia@ You Bung folders to TTafeDts iMmk faster. 213 [?®0B[jafi®Drjfl 40 is (SoOOogj® gtssrjiBGariy tsm<s5xps@G(§tlI ITCD® esiDDorpo/Js Bs a DDD®<3CM?GII (SDB(Sorjaai„ (pAsasamG aracil f?QflrjTi@Gfi®OTjaD Y®E]'RS fifelaL rpDaecsS V®QO wafccs (MJDDD Haglfe G® sGairGo (SRBarjDDo GBa@to G® §GapG„ i You give the Sheffield building a face-lift, it still looks horrible. Conference Hey ho, miss a go. Office doesn't buy new flow furniture. ir failing Take an extra I. Move go. steps back. start Place one Infamou chunk of asbestos raer shopS<ee| player on this square, », roll a die, and try your Southsid luck at the CAMPUS £0.5 mil nuclear reactor ^ RENAISSANCE GAME ^ ill. -

Kenny G Bio 2018

A phenomenally successful instrumentalist whose recordings routinely made the pop, R&B, and jazz charts during the 1980s and ’90s, Kenny G‘s sound became a staple on adult contemporary and smooth jazz radio stations. He’s a fine player with an attractive sound (influenced a bit by Grover Washington, Jr.) who often caresses melodies, putting a lot of emotion into his solos. Because he does not improvise much (sticking mostly to predictable melody statements), his music largely falls outside of jazz. However, because he is listed at the top of “contemporary jazz” charts and is identified with jazz in the minds of the mass public, he is classified as jazz. Kenny Gorelick started playing professionally with Barry White‘s Love Unlimited Orchestra in 1976. He recorded with Cold, Bold & Together (a Seattle-based funk group) and freelanced locally. After graduating from the University of Washington, Kenny G worked with Jeff Lorber Fusion, making two albums with the group. Soon he was signed to Arista, recording his debut as a leader in 1982. His fourth album, Duotones(which included the very popular “Songbird”), made him into a star. Soon he was in demand for guest appearances on recordings of such famous singers as Aretha Franklin, Whitney Houston, and Natalie Cole. Kenny G’s own records have sold remarkably well, particularly Breathless, which has easily topped eight million copies in the U.S.; his total album sales top 30 million copies. The holiday album Miracles, released in 1994, and 1996’s Moment continued the momentum of his massive commercial success. He also recorded his own version of the Celine Dion/Titanic smash “My Heart Will Go On” in 1998, but the following year he released Classics in the Key of G, a collection of jazz standards like “‘Round Midnight” and “Body and Soul,” possibly to reclaim some jazz credibility. -

Downbeat.Com March 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. DOWNBEAT.COM MARCH 2014 D O W N B E AT DIANNE REEVES /// LOU DONALDSON /// GEORGE COLLIGAN /// CRAIG HANDY /// JAZZ CAMP GUIDE MARCH 2014 March 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 3 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Kathleen Costanza Design Intern LoriAnne Nelson ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene -

Guide to the Martin Williams Collection

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago CBMR Collection Guides / Finding Aids Center for Black Music Research 2020 Guide to the Martin Williams Collection Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cmbr_guides Part of the History Commons, and the Music Commons Columbia COLLEGE CHICAGO CENTER FOR BLACK MUSIC RESEARCH COLLECTION The Martin Williams Collection,1945-1992 EXTENT 7 boxes, 3 linear feet COLLECTION SUMMARY Mark Williams was a critic specializing in jazz and American popular culture and the collection includes published articles, unpublished manuscripts, files and correspondence, and music scores of jazz compositions. PROCESSING INFORMATION The collection was processed, and a finding aid created, in 2010. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Martin Williams [1924-1992] was born in Richmond Virginia and educated at the University of Virginia (BA 1948), the University of Pennsylvania (MA 1950) and Columbia University. He was a nationally known critic, specializing in jazz and American popular culture. He wrote for major jazz periodicals, especially Down Beat, co-founded The Jazz Review and was the author of numerous books on jazz. His book The Jazz Tradition won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in music criticism in 1973. From 1971-1981 he directed the Jazz and American Culture Programs at the Smithsonian Institution, where he compiled two widely respected collections of recordings, The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz, and The Smithsonian Collection of Big Band Jazz. His liner notes for the latter won a Grammy Award. SCOPE & CONTENT/COLLECTION DESCRIPTION Martin Williams preferred to retain his writings in their published form: there are many clipped articles but few manuscript drafts of published materials in his files. -

Labour Students Caught in Postal Vote Scandal

That Friday free thing Leeds St de Friday, May 4, 2007 VOL37:ISSUE 20 Labour students caught in postal vote scandal By Alex Doorey continued involvement with the Leeds certainly be expelled from the Labour branch of the Labour Party_ A party and face criminal charges." he spokesperson for the Lib Dems said said. that they were 'appalled' at the Responding to the Sunday Times MON 4 -SAT 9 JUNE Opposition parties have rounded on 'alleged disgraceful behaviour of allegations. David Crompton. the student Labour movement On Leeds University students whilst out assistant chief constable of West campus over claims that its members canvassing for Labour in Gipton and Yorkshire Police, said: "This is DIRECT FROM THE WEST END have been involved in the alleged Harehills'. extremely sharp practice and a.clear postal vote fraud scandal. These concerns have been echoed breach of the guidelines." tra_ I NG 0 The movement has remained tight- by Liberal Democrat Council Leader Wilson went on to say that. if the fHilu PIM ISIS lipped since allegations were made in Mark Harris. who said: "This is a claims were true. it would reflect the the national press on Sunday that ii disgrace. This matter needs to be difficulties that Labour were facing in I had been involved in the dubious thoroughly investigated." the local elections. collection of postal ballots for Simon Harley, Chairperson of "It is too early to say whether the yesterdays local elections. Leeds Conservative Future, made no allegations are true or not, but if they A spokesperson for the student comment on the counter-accusations are. -

FINAL AGENDA AUTUMN ONLINE CONFERENCE 2-11 October 2020

FINAL AGENDA AUTUMN ONLINE CONFERENCE 2-11 October 2020 9 1 CONTENTS Table of Contents 2 Section A (Enabling Motions) 10 Enabling Motions A01 Standing Orders Committee (SOC) Report 10 Enabling Motions A02 Amendments to Standing Orders for the Conduct of Conference 11 to enable an online and telephone Extraordinary Conference to be held in Autumn 2020 Enabling Motions A03 Enabling Motion for an Extraordinary Autumn Conference 2020 12 to be held online Section A – Main Agenda 14 A1 Standing Orders Committee Report 14 A2 Green Party Executive Report 37 A3 Treasurers Report 46 A4 Green Party Regional Council Report 47 A5 Dispute Resolution Committee Report 50 A6 Policy Development Committee Report 54 A7 Complaint Managers Report 57 A8 Campaigns Committee Report 58 A9 Conferences Committee Report 58 A10 Equality and Diversity Committee Report 58 A11 Green World Editorial Board Report 58 A12 Framework Development Group report 58 A13 Climate Emergency Policy Working Group Report 58 Section B 60 B1 Food and Agriculture Voting Paper 60 Amendment 2a 60 Amendment 1a 61 Amendment 2b 61 Amendment 1b 61 Amendment 1c 62 Amendment 1d 62 Amendment 2c 64 2 3 Section C 65 C1 Deforestation (Fast Tracked) 65 C2 Car and vans to go zero carbon by 2030 65 C3 Ban on advertising of high-carbon goods and services 65 C4 The 2019 General Election Manifesto and Climate Change Mitigation 66 Amendment 1 67 Amendment 2 67 C5 Adopt the Principle of Rationing to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions Arising from Travel, 67 Amending the Climate Emergency and the Transport Chapters of PSS C6 Updating the philosophical basis to reflect doughnut economics 68 Amendment 1 69 C7 Self Declaration of Gender 69 C8 Animal Rights: Fireworks; limit use and quiet 70 C9 Access to Fertility Treatment 70 Section D 71 D1 Winning over workers is crucial to fighting climate change. -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven.