Why Hip-Hop Is Queer: Using Queer Theory to Examine Identity Formation in Rap Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Puma Kylie Rihanna 1

Buzz Queens Why Rihanna and Kylie Jenner are critical to Puma’s ambitious new women’s push. By Sheena Butler-Young GE CHINSEE R O E S: G R THE O L AL AND; R B F O Y S E T R U O C : BU AM J OCK; ST R SHUTTE X Behind S: LEPORE: RE the scenes ofO a recent FentyOT design meetingPH ver Easter weekend, why Puma is making the trendset- are nothing new, but the German Rihanna was relishing ting songstress a cornerstone of its footwear-and-apparel maker’s col- a rare few hours of business strategy. laborations with two of pop culture’s O downtime in New But the brand isn’t stopping there. most influential women are not of Last week, the highly anticipated the garden variety. from her Anti World Tour. Scores sneaker from Puma’s campaign with Rihanna, Puma’s women’s creative of paparazzi snapped flicks of the Kylie Jenner hit stores, fueling a new director since December 2014, and UMA P star as she ran errands in a black wave of buzz after the queen of social Kylie Jenner, the brand’s newest F O Vetements hoodie and fur slides media teased her partnership for the ambassador, represent a strategic Y S E T from her Fenty x Puma collection. past month on Instagram. R U O Make no mistake about it: Puma to the women’s market in an unprec- C S: Rihanna’s every fashion move is a is serious about girl power. edented way. O OT statement for the masses. -

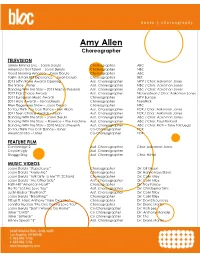

Amy Allen Choreographer

Amy Allen Choreographer TELEVISION Jimmy Kimmel Live – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC America’s Got Talent – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC Good Morning America – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC 106th & Park BET Experience – Jason Derulo Choreographer BET 2013 MTV Movie Awards Opening Asst. Choreographer MTV / Chor: Aakomon Jones The Voice – Usher Asst. Choreographer NBC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – 2013 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2012 Kids Choice Awards Asst. Choreographer Nickelodeon / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 European Music Awards Choreographer MTV Europe 2011 Halo Awards – Jason Derulo Choreographer TeenNick Ellen Degeneres Show – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC So You Think You Can Dance – Keri Hilson Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 Teen Choice Awards – Jason Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Jason Derulo Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Florence + The Machine Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Paul Kirkland Dancing With the Stars – 2010 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Rich + Tone Talauega So You Think You Can Dance – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX American Idol – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX FEATURE FILM Centerstage 2 Asst. Choreographer Chor: Aakomon Jones Coyote Ugly Asst. Choreographer Shaggy Dog Asst. Choreographer Chor: Hi Hat MUSIC VIDEOS Jason Derulo “Stupid Love” Choreographer Dir: Gil Green Jason Derulo “Marry Me” Choreographer Dir: Hannah Lux Davis Jason Derulo “Talk Dirty To Me” ft. 2Chainz Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Jason Derulo “The Other Side” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Faith Hill “American Heart” Choreographer Dir: Trey Fanjoy Ne-Yo “Let Me Love You” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Christopher Sims Justin Bieber “Boyfriend” Asst. -

A$Ap Rocky Injured Generation Tour 18-City

A$AP ROCKY INJURED GENERATION TOUR 18-CITY NORTH AMERICAN TOUR KICKS OFF TUESDAY, JANUARY 8 TICKETS ON SALE FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 2 October 29, 2018 – New York – A$AP Rocky will be hitting the road this winter with his Injured Generation Tour. The 18-city North American tour kicks off on Tuesday, January 8th in Minneapolis at The Armory, and will make stops in Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, Atlanta and more, before wrapping on Wednesday, February 6th in Kent, WA at accesso ShoWare Center. The tour is produced by AEG Presents. Tickets for A$AP Rocky’s Injured Generation Tour go on sale Friday, November 2nd at 12 noon local time. A$AP Rocky Fan Presale will begin Tuesday October 30th at 10am local time through Thursday, November 1st at 10pm local time. American Express® Card Members can purchase tickets before the general public beginning Tuesday, October 30th at 12 noon local time, through Thursday, November 1st at 10pm local time. For more information and to purchase tickets please visit: https://tstng.co/shows.html The tour comes on the heels of the release of A$AP Rocky’s highly-anticipated third studio album, TESTING, which has garnered over 1 billion streams worldwide, landing at #1 on the iTunes charts in 16 countries upon release. TESTING launches a new era for Rocky, exploring new sounds and ideas in an unparalleled musical landscape where he continues to break the mainstream mindset with sonics rarely heard in hip-hop. This album picks up where Rocky last left off, weaving mind-melting aural psychedelics into hip-hop that is, at times dark and confessional, and in other moments uplifting and celebratory. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS December 4, 1973 Port on S

39546 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS December 4, 1973 port on S. 1443, the foreign aid author ADJOURNMENT TO 11 A.M. Joseph J. Jova, of Florida, a Foreign Serv ization bill. ice officer of the class of career minister, to Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Mr. Presi be Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipo There is a time limitaiton thereon. dent, if there be no further business to tentiary of the United States of America to There will be at least one yea-and-nay come before the Senate, I move, in ac Mexico. vote, I am sure, on the adoption of the cordance with the previous order, that Ralph J. McGuire, of the District of Colum. bia, a Foreign Service officer of class 1, to be conference report, and there may be the Senate stand in adjournment until Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipoten other votes. the hour of 11 o'clock a.m. tomorrow. t iary cf the United States of America to the On the disposition of the conference The motion was agreed to; and at 6: 45 Republic of Mali. report on the foreign aid authorization p.m., the Senate adjourned until tomor Anthony D. Marshall, of New York, to be row, Wednesday, December 5, 1973, at Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipoten bill, S. 1443, the Senate will take up tiary of the United States of America to the Calendar Order No. 567, S. 1283, the so lla.m. Republic of Kenya. called energy research and development Francis E. Meloy, Jr., of the District of bill. I am sure there will be yea and Columbia, a Foreign Service officer of the NOMINATIONS class of career minister, to be Amb1ssador nay votes on amendments thereto to Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the morrow. -

Cuba “Underground”: Los Aldeanos, Cuban Hip-Hop and Youth Culture

Cuba “Underground”: Los Aldeanos, Cuban Hip-Hop and Youth Culture Manuel Fernández University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Occasional Paper #97 c/o Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee PO Box 413 Milwaukee, WI 53201 http://www4.uwm.edu/clacs/ [email protected] Fernández 1 Cuba “Underground”: Los Aldeanos, Cuban Hip-Hop and Youth Culture Manuel Fernández The genre most frequently mentioned in U.S. university textbooks and anthologies when discussing Cuba’s recent musical production is the nueva trova , which developed soon after Fidel Castro came to power. The first edition of Más allá de las palabras (2004), to cite just one example of an intermediate Spanish language textbook, uses the trovistas Pablo Milanés and Silvio Rodríguez as examples of “contemporary” Cuban musical artists (204). Books on Cuba aimed at monolingual English speakers also depend largely on the nueva trova when attempting to present Cuba’s current musical production. The Cuba Reader: History, Culture, Politics (2003), an anthology of texts dating back to Columbus, uses samples from Silvio Rodríguez’s music on two occasions, in a chapter dedicated to the international aspects and impact of the Cuban Revolution and once again in a chapter dedicated to Cuba after the fall of the Soviet Union. Without discounting the artistic merit and endurance of the nueva trova or the numerous trovistas , the use of this music (the heyday of which was primarily in the 1960s to early 1980s) as a cultural marker for Cuban culture today seems distinctly anachronistic. It would be analogous to using music from World War II era United States to describe the events and sentiments of the 1960s. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

A King Named Nicki: Strategic Queerness and the Black Femmecee

Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory ISSN: 0740-770X (Print) 1748-5819 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rwap20 A king named Nicki: strategic queerness and the black femmecee Savannah Shange To cite this article: Savannah Shange (2014) A king named Nicki: strategic queerness and the black femmecee, Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, 24:1, 29-45, DOI: 10.1080/0740770X.2014.901602 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/0740770X.2014.901602 Published online: 14 May 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 2181 View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rwap20 Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, 2014 Vol. 24, No. 1, 29–45, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0740770X.2014.901602 A king named Nicki: strategic queerness and the black femmecee Savannah Shange* Department of Africana Studies and the Graduate School of Education, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States This article explores the deployment of race, queer sexuality, and femme gender performance in the work of rapper and pop musical artist Nicki Minaj. The author argues that Minaj’s complex assemblage of public personae functions as a sort of “bait and switch” on the laws of normativity, where she appears to perform as “straight” or “queer,” while upon closer examination, she refuses to be legible as either. Rather than perpetuate notions of Minaj as yet another pop diva, the author proposes that Minaj signals the emergence of the femmecee, or a rapper whose critical, strategic performance of queer femininity is inextricably linked to the production and reception of their rhymes. -

Diddy Ft Chris Brown Lyrics

Diddy ft chris brown lyrics Yesterday Lyrics: Yesterday I fell in love, today feels like my funeral / I just got hit by a bus, shouldn't Featuring Chris Brown [Verse 1: Diddy & Chris Brown]. Lyrics to "Yesterday" song by Diddy - Dirty Money: Yesterday I fell in love Diddy - Dirty Money Lyrics. "Yesterday" (feat. Chris Brown). [Chorus - Chris Brown]. So I just made an Instagram and a Twitter, It would make me happy if everyone went and followed me. Here are. Music video by Diddy - Dirty Money performing Yesterday. One reason why I love Chris Brown is 1:He. Lyrics of YESTERDAY by Puff Daddy feat. Chris Brown and Dirty Money: Chorus Chris Brown, Yesterday I fell in love, Today [Verse 1: Diddy]. Lyrics for Yesterday by Diddy - Dirty Money feat. Chris Brown. [Chorus- Chris Brown] Yesterday I fell in love Today feels like my funeral I just got. Yesterday Songtext von Diddy - Dirty Money feat. Chris Brown mit Lyrics, deutscher Übersetzung, Musik-Videos und Liedtexten kostenlos auf Yesterday (feat Diddy Dirty Money) lyrics performed by Chris Brown: [Refrain/Couplet 1 - Chris Brown] Yesterday I fell in love Today feels like my funeral I just got. Diddy-Dirty Money - Yesterday Lyrics ft. Chris Brown [Chorus- Chris Brown] Yesterday I fell in love Today feels like my funeral I just got hit b. [Chorus- Chris Brown] Yesterday I fell in love. Today feels like my funeral. I just got hit by a bus. Shouldn've been so beautiful. Don't know why I gave my heart. Lyrics to 'Yesterday (Feat Chris Brown)' by DIDDY: [Chorus- Chris Brown] / Yesterday I fell in love / Today feels like my funeral / I just got hit by a bus. -

Alma's Good Trip Mikko Joensuu in Holy Water Hippie Queen of Design Frank Ocean of Love Secret Ingredients T H Is Is T H E M

FLOW MAGAZINE THIS IS THE MAGAZINE OF FLOW FESTIVAL. FESTIVAL. FLOW OF IS THE MAGAZINE THIS ALMA'S GOOD TRIP MIKKO JOENSUU IN HOLY WATER HIPPIE QUEEN OF DESIGN FRANK OCEAN OF LOVE SECRET INGREDIENTS F entrance L 7 OW F L O W the new This is 1 to 0 2 2 0 1 7 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 6–9 12–13 18–21 36–37 Editor 7 7 W Tero Kartastenpää POOL OF ALMA Alma: ”We never really traveled when we were Art Director little. Our parents are both on disability Double Happiness pension and we didn’t IN SHORT have loads of money. Swimming with a Whenever our classmates Designers singer-songwriter. traveled to Thailand Featuring Mikko MINT MYSTERY SOLVED or Tenerife for winter Viivi Prokofjev SHH Joensuu. holidays we took a cruise AIGHT, LOOK to Tallinn. When me and Antti Grundstén 22–27 Anna turned eighteen we Frank Ocean sings about Robynne Redgrave traveled to London with love and God and God and our friends. We stayed for love. Here's what you didn’t five days, drunk.” 40–41 Subeditor know about alt-country star Ryan Adams. Aurora Rämö Alma went to L.A. and 14–15 met everybody. Publisher 34–37 O The design hippie Laura Flow Festival Ltd. 1 1 Väinölä creates a flower ALWAYS altar for yoga people. Lana Del Rey’s American Contributors nightmares, plant cutting 30–33 Hanna Anonen craze, the smallest talk etc. The most quiet places OCEAN OF TWO LOVES Maija Astikainen from abandoned villas to Pauliina Holma Balloon stage finds new UNKNOWN forgotten museums. -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

TUULETAR Tules, Maas, Vedes, Taivaal (Fire, Earth, Water, Sky) (Bafe's Factory)

TUULETAR Tules, Maas, Vedes, Taivaal (Fire, Earth, Water, Sky) (Bafe's Factory) Among the most promising pop vocal groups in Finland and Scandinavia today—the modern girl-group sound of Tuuletar comes alive on their much anticipated first album Tules, Maas, Vedes, Taivaal. The eight song CD was superbly recorded and produced at Liquid 5th studios based in North Carolina. Visiting and performing in New York on the way back to Finland, Tuuletar can't wait to bring their “Folk-Hop” sound — accapella vocals all sung in their native Finnish—to the attention of music fans World Wide. The skillful production by the Liquid 5th team shines a bright light on Tuuletar’s phenomenal pop vocal approach. For music listeners challenged by the unusual complexities of the Finnish language, Tuuletar’s album title translates to “Fire, Earth, Water, Sky”, with each group member representing a different element or sign. At the core of the Tuuletar sound are four accomplished singers—Sini Koskelainen, Piia Säilynoja, Johanna Kyykoski and the band’s human Beat-Boxer / singer Venla Ilona Blom. With Venla supplying the percussive beat-boxing sounds, and the impressive production of Liquid 5th putting on the sheen, Tuuletar’s vocal arrangements are fully realized on their CD debut. Commenting on the unique Tuuletar sound in the following interview, Sini Koskelainen tells mwe3.com, “Beat-boxing is a form of vocal percussion primarily involving the art of mimicking drum machines using one’s mouth, lips, tongue and voice. The folk-hop sound blends Finnish folk music with hip-hop, electronic music and world music.” The perfect showcase for their unique talents as a group, the debut Tuuletar album is filled with appealing vocal harmonies yet the music is also quite experimental sounding.