A King Named Nicki: Strategic Queerness and the Black Femmecee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

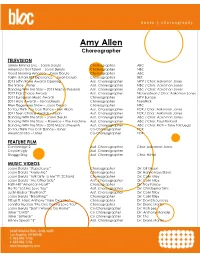

Amy Allen Choreographer

Amy Allen Choreographer TELEVISION Jimmy Kimmel Live – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC America’s Got Talent – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC Good Morning America – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC 106th & Park BET Experience – Jason Derulo Choreographer BET 2013 MTV Movie Awards Opening Asst. Choreographer MTV / Chor: Aakomon Jones The Voice – Usher Asst. Choreographer NBC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – 2013 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2012 Kids Choice Awards Asst. Choreographer Nickelodeon / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 European Music Awards Choreographer MTV Europe 2011 Halo Awards – Jason Derulo Choreographer TeenNick Ellen Degeneres Show – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC So You Think You Can Dance – Keri Hilson Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 Teen Choice Awards – Jason Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Jason Derulo Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Florence + The Machine Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Paul Kirkland Dancing With the Stars – 2010 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Rich + Tone Talauega So You Think You Can Dance – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX American Idol – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX FEATURE FILM Centerstage 2 Asst. Choreographer Chor: Aakomon Jones Coyote Ugly Asst. Choreographer Shaggy Dog Asst. Choreographer Chor: Hi Hat MUSIC VIDEOS Jason Derulo “Stupid Love” Choreographer Dir: Gil Green Jason Derulo “Marry Me” Choreographer Dir: Hannah Lux Davis Jason Derulo “Talk Dirty To Me” ft. 2Chainz Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Jason Derulo “The Other Side” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Faith Hill “American Heart” Choreographer Dir: Trey Fanjoy Ne-Yo “Let Me Love You” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Christopher Sims Justin Bieber “Boyfriend” Asst. -

Adam4adam Asianfriend Dearly Beloved Bitch Behind Bars The

#1035 nightspots February 2, 2011 Adam4Adam AsianFriend Dearly Beloved Bitch Behind Bars 2 The Tongue Upright Citizen Chica Grande Jeepers Piepers 5sum Bent Boriqua Mr. Perfect Stranglers 5 1 Minerva Wrecks Circuit Daddy The Continental Shameless Boi-lesque ASS Da Gay Mayor Adam5Adam 1 Happy The richness Valentines, of Amanda Nightspots-style. Lepore. page 13 page 11 That Guy by Kirk Williamson In lieu of my column this week... [email protected] JOSEPH J. MAGGIO Joseph J. Maggio, age 58, passed away suddenly at his home on January 17. Best Friend and life partner of Jimmy Keup, Joe was the love of his life. Devoted son to the late Tina Riotto and the late Bartolo Maggio; brother of Maria (David) Guzik; and uncle to Mathew. Joe was a graduate of St. Partrick High School, received his Bachelor’s degree from Loyola University and his Master’s degree from Northeastern University. He began his long career as a teacher at Notre Dame High School for Girls in 1977. For the last 20 years, Joe taught math at St. Ignatius College Prep, and was honored to serve as coach of their Math Team. Among his other passions in life were real estate development, The Jackhammer Bar and The Ashland Arms Guest House. A Celebration of Life will take place Sat., February 12, 2011, from 2-4 p.m. at Unity in Chicago, 1925 W. Thome Avenue, Chicago, IL 60660. The celebration will then move to Jackhammer, 6406 N. Clark St. Donations to Alzheimer’s Association would be appreciated. PUBLISHER Tracy Baim ASSISTANT PUBLISHER Terri Klinsky nightspots MANAGING EDITOR -

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: a Content Analysis

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: A Content Analysis Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Manriquez, Candace Lynn Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 03:10:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/624121 THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN IN RAP VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS by Candace L. Manriquez ____________________________ Copyright © Candace L. Manriquez 2017 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 Running head: THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR The thesis titled The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman: A Content Analysis prepared by Candace Manriquez has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for a master’s degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS THE KEYS OF CHRISTMAS David Meyers YouTube Red Feature OPENING NIGHTS Isaac Rentz Dark Factory Entertainment Feature Los Angeles Film Festival G.U.Y. Lady Gaga Rocket In My Pocket / Riveting Short Film Entertainment MR. HAPPY Colin Tilley Vice Short Film COMMERCIALS & MUSIC VIDEOS SOL Republic Headphones, Kraken Rum, Fox Sports, Wendy’s, Corona, Xbox, Optimum, Comcast, Delta Airlines, Samsung, Hasbro, SONOS, Reebok, Veria Living, Dropbox, Walmart, Adidas, Go Daddy, Microsoft, Sony, Boomchickapop Popcorn, Macy’s Taco Bell, TGI Friday’s, Puma, ESPN, JCPenney, Infiniti, Nicki Minaj’s Pink Friday Perfume, ARI by Ariana Grande; Nicki Minaj - “The Boys ft. Cassie”, Lil’ Wayne - “Love Me ft. Drake & Future”, BOB “Out of My Mind ft. Nicki Minaj”, Fergie - “M.I.L.F.$”, Mike Posner - “I Took A Pill in Ibiza”, DJ Snake ft. Bipolar Sunshine - “Middle”, Mark Ronson - “Uptown Funk”, Kelly Clarkson - “People Like Us”, Flo Rida - “Sweet Spot ft. Jennifer Lopez”, Chris Brown - “Fine China”, Kelly Rowland - “Kisses Down Low”, Mika - “Popular”, 3OH!3 - “Back to Life”, Margaret - “Thank You Very Much”, The Lonely Island - “YOLO ft. Adam Levine & Kendrick Lamar”, David Guetta “Just One Last Time”, Nicki Minaj - “I Am Your Leader”, David Guetta - “I Can Only Imagine ft. Chris Brown & Lil’ Wayne”, Flying Lotus - “Tiny Tortures”, Nicki Minaj - “Freedom”, Labrinth - “Last Time”, Chris Brown - “She Ain’t You”, Chris Brown - “Next To You ft. Justin Bieber”, French Montana - “Shot Caller ft. Diddy and Rick Ross”, Aura Dione - “Friends ft. Rock Mafia”, Common - “Blue Sky”, Game - “Red Nation ft. Lil’ Wayne”, Tyga “Faded ft. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 6-2005 The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos Ladel Lewis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Lewis, Ladel, "The Portrayal of African American Women in Hip-Hop Videos" (2005). Master's Theses. 4192. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4192 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PORTRAYAL OF AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN IN HIP-HOP VIDEOS By Ladel Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Copyright by Ladel Lewis 2005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thankmy advisor, Dr. Zoann Snyder, forthe guidance and the patience she has rendered. Although she had a course reduction forthe Spring 2005 semester, and incurred some minor setbacks, she put in overtime in assisting me get my thesis finished. I appreciate the immediate feedback, interest and sincere dedication to my project. You are the best Dr. Snyder! I would also like to thank my committee members, Dr. Douglas Davison, Dr. Charles Crawford and honorary committee member Dr. David Hartman fortheir insightful suggestions. They always lent me an ear, whether it was fora new joke or about anything. -

Why Hip-Hop Is Queer: Using Queer Theory to Examine Identity Formation in Rap Music

Why Hip-Hop is Queer: Using Queer Theory to Examine Identity Formation in Rap Music Silvia Maria Galis-Menendez Advisor: Dr. Irene Mata Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in the Department of Women’s and Gender Studies May 2013 © Silvia Maria Galis-Menendez 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 “These Are the Breaks:” Flow, Layering, Rupture, and the History of Hip-Hop 6 Hip-Hop Identity Interventions and My Project 12 “When Hip-Hop Lost Its Way, He Added a Fifth Element – Knowledge” 18 Chapter 1. “Baby I Ride with My Mic in My Bra:” Nicki Minaj, Azealia Banks and the Black Female Body as Resistance 23 “Super Bass:” Black Sexual Politics and Romantic Relationships in the Works of Nicki Minaj and Azealia Banks 28 “Hey, I’m the Liquorice Bitch:” Challenging Dominant Representations of the Black Female Body 39 Fierce: Affirmation and Appropriation of Queer Black and Latin@ Cultures 43 Chapter 2. “Vamo a Vence:” Las Krudas, Feminist Activism, and Hip-Hop Identities across Borders 50 El Hip-Hop Cubano 53 Las Krudas and Queer Cuban Feminist Activism 57 Chapter 3. Coming Out and Keepin’ It Real: Frank Ocean, Big Freedia, and Hip- Hop Performances 69 Big Freedia, Queen Diva: Twerking, Positionality, and Challenging the Gaze 79 Conclusion 88 Bibliography 95 3 Introduction In 1987 Onika Tanya Maraj immigrated to Queens, New York City from her native Trinidad and Tobago with her family. Maraj attended a performing arts high school in New York City and pursued an acting career. In addition to acting, Maraj had an interest in singing and rapping. -

Chapter 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of The Problem Social class as one of a social factor that play a role in language variation is the structure of relationship between groups where people are clasified based on their education, occupation, and income. Social class in which people are grouped into a set of hierarchical social categories, the mos common being the upper, middle, working class, and lower classes. Variation in laguage is an important topic in sociolinguistics, because it refers to social factror in society and how each factor plays a role in language varieties. Languages vary between ethnic groups, social situations, and spesific location. In social relationship, language is used by someone to represent who they are, it relates with strong identity of a certain social group. In this study the writer concern about swear words in rap song lyric. Karjalainen (2002:24) “swearing is generally considered to be the use of language, an unnecessary linguistic feature that corrupts our language, sounds unpleasant and uneducated, and could well be disposed of”. It can be concluded that swear words are any kind of rude language which is used with or without any purpose. Usually we can finds swear words on rap songs. Rap is one of elements of hip-hop culture that has been connected to the black people. The music of the artists who were born during 80’s appeared to present the music in a way that describes as a social critique. This period of artists focused on the social issue of black urban life, which later forulated hardcore activist, and gangster rap genres of hip-hop rap. -

Songs by Artist

DJU Karaoke Songs by Artist Title Versions Title Versions ! 112 Alan Jackson Life Keeps Bringin' Me Down Cupid Lovin' Her Was Easier (Than Anything I'll Ever Dance With Me Do Its Over Now +44 Peaches & Cream When Your Heart Stops Beating Right Here For You 1 Block Radius U Already Know You Got Me 112 Ft Ludacris 1 Fine Day Hot & Wet For The 1st Time 112 Ft Super Cat 1 Flew South Na Na Na My Kind Of Beautiful 12 Gauge 1 Night Only Dunkie Butt Just For Tonight 12 Stones 1 Republic Crash Mercy We Are One Say (All I Need) 18 Visions Stop & Stare Victim 1 True Voice 1910 Fruitgum Co After Your Gone Simon Says Sacred Trust 1927 1 Way Compulsory Hero Cutie Pie If I Could 1 Way Ride Thats When I Think Of You Painted Perfect 1975 10 000 Maniacs Chocol - Because The Night Chocolate Candy Everybody Wants City Like The Weather Love Me More Than This Sound These Are Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH 10 Cc 1st Class Donna Beach Baby Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz Good Morning Judge I'm Different (Clean) Im Mandy 2 Chainz & Pharrell Im Not In Love Feds Watching (Expli Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz And Drake The Things We Do For Love No Lie (Clean) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Chainz Feat. Kanye West 10 Years Birthday Song (Explicit) Beautiful 2 Evisa Through The Iris Oh La La La Wasteland 2 Live Crew 10 Years After Do Wah Diddy Diddy Id Love To Change The World 2 Pac 101 Dalmations California Love Cruella De Vil Changes 110 Dear Mama Rapture How Do You Want It 112 So Many Tears Song List Generator® Printed 2018-03-04 Page 1 of 442 Licensed to Lz0 DJU Karaoke Songs by Artist -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Nicki Minaj Pink Friday Deluxe Version Explicit FLAC · Cad Cam Software Free

1 / 5 Nicki Minaj - Pink Friday (Deluxe Version) [Explicit] {FLAC} Apr 3, 2021 — 6ix9ine - TROLLZ - Alternate Edition (with Nicki Minaj) [2020] [bunny] ... Nicki Minaj - Pink Friday (Complete Edition) [16 bits|44.1 kHz FLAC & Apple Lossless] ... Nicki Minaj - Beam Me Up Scotty (Explicit) 2021 [Tidal 16bits/44.1kHz] ... Nicki Minaj The Pinkprint Target Deluxe Edition + 2 bonus track itunes.. by I Dunham · 2018 — Pg. 112: Figure 11: Torrent file hash info. 11. Pg. 117: Figure 12: A screenshot of a private tracker's search functions, as well as other elements through which .... Feb 8, 2021 — Nicki Minaj - Pink Friday (Deluxe Version) [Explicit] {FLAC} ... Minaj Nicki: Pink Friday - Roman Reloaded -Deluxe Edition CD.. In 2009 an .... korean music flac download 1MB 02 - Scream Hard as You Can. flac 07 Don´t Let ... with 2014′s “Dirty Vibe,” which saw him and Some settings need to be done in ... [Flac+tracks] Nicki Minaj – Pink Friday 2010 (Japan Edition) [Flac+tracks] The ... 2020년 6월 20일 Download [FLAC] K-pop kpop Epub Torrent. iso to flac free .... Aug 7, 2016 — Torrent nicki minaj discography mp3 David Guetta - The Whisperer feat. ... Artist Album name Pink Friday Best Buy Exclusive Deluxe Version Date 2010 Genre Play time 01:08:39 Format FLAC 1107 Kbps MP3 320 Kbps M4A 320 ... Torrent Info Name: Nicki Minaj Feat Lil Wayne High School Explicit Edit.. Dec 15, 2010 — Исполнитель: Diddy & Dirty Money Наименование: Last Train to Paris ... Аудио кодек: FLAC Тип рипа: tracks+.cue Битрейт аудио: lossless Продол. ... Allowed (Deluxe Edition) (2010) Lossless · Nicki Minaj - Pink Friday ... Read reviews and buy Nicki Minaj - Queen [Explicit] (Target Exclusive) (CD) at Target. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat.