Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: a Content Analysis

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: A Content Analysis Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Manriquez, Candace Lynn Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 03:10:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/624121 THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN IN RAP VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS by Candace L. Manriquez ____________________________ Copyright © Candace L. Manriquez 2017 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 Running head: THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR The thesis titled The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman: A Content Analysis prepared by Candace Manriquez has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for a master’s degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

A King Named Nicki: Strategic Queerness and the Black Femmecee

Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory ISSN: 0740-770X (Print) 1748-5819 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rwap20 A king named Nicki: strategic queerness and the black femmecee Savannah Shange To cite this article: Savannah Shange (2014) A king named Nicki: strategic queerness and the black femmecee, Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, 24:1, 29-45, DOI: 10.1080/0740770X.2014.901602 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/0740770X.2014.901602 Published online: 14 May 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 2181 View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rwap20 Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, 2014 Vol. 24, No. 1, 29–45, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0740770X.2014.901602 A king named Nicki: strategic queerness and the black femmecee Savannah Shange* Department of Africana Studies and the Graduate School of Education, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States This article explores the deployment of race, queer sexuality, and femme gender performance in the work of rapper and pop musical artist Nicki Minaj. The author argues that Minaj’s complex assemblage of public personae functions as a sort of “bait and switch” on the laws of normativity, where she appears to perform as “straight” or “queer,” while upon closer examination, she refuses to be legible as either. Rather than perpetuate notions of Minaj as yet another pop diva, the author proposes that Minaj signals the emergence of the femmecee, or a rapper whose critical, strategic performance of queer femininity is inextricably linked to the production and reception of their rhymes. -

Songs by Artist

DJU Karaoke Songs by Artist Title Versions Title Versions ! 112 Alan Jackson Life Keeps Bringin' Me Down Cupid Lovin' Her Was Easier (Than Anything I'll Ever Dance With Me Do Its Over Now +44 Peaches & Cream When Your Heart Stops Beating Right Here For You 1 Block Radius U Already Know You Got Me 112 Ft Ludacris 1 Fine Day Hot & Wet For The 1st Time 112 Ft Super Cat 1 Flew South Na Na Na My Kind Of Beautiful 12 Gauge 1 Night Only Dunkie Butt Just For Tonight 12 Stones 1 Republic Crash Mercy We Are One Say (All I Need) 18 Visions Stop & Stare Victim 1 True Voice 1910 Fruitgum Co After Your Gone Simon Says Sacred Trust 1927 1 Way Compulsory Hero Cutie Pie If I Could 1 Way Ride Thats When I Think Of You Painted Perfect 1975 10 000 Maniacs Chocol - Because The Night Chocolate Candy Everybody Wants City Like The Weather Love Me More Than This Sound These Are Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH 10 Cc 1st Class Donna Beach Baby Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz Good Morning Judge I'm Different (Clean) Im Mandy 2 Chainz & Pharrell Im Not In Love Feds Watching (Expli Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz And Drake The Things We Do For Love No Lie (Clean) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Chainz Feat. Kanye West 10 Years Birthday Song (Explicit) Beautiful 2 Evisa Through The Iris Oh La La La Wasteland 2 Live Crew 10 Years After Do Wah Diddy Diddy Id Love To Change The World 2 Pac 101 Dalmations California Love Cruella De Vil Changes 110 Dear Mama Rapture How Do You Want It 112 So Many Tears Song List Generator® Printed 2018-03-04 Page 1 of 442 Licensed to Lz0 DJU Karaoke Songs by Artist -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Nicki Minaj Pink Friday Deluxe Version Explicit FLAC · Cad Cam Software Free

1 / 5 Nicki Minaj - Pink Friday (Deluxe Version) [Explicit] {FLAC} Apr 3, 2021 — 6ix9ine - TROLLZ - Alternate Edition (with Nicki Minaj) [2020] [bunny] ... Nicki Minaj - Pink Friday (Complete Edition) [16 bits|44.1 kHz FLAC & Apple Lossless] ... Nicki Minaj - Beam Me Up Scotty (Explicit) 2021 [Tidal 16bits/44.1kHz] ... Nicki Minaj The Pinkprint Target Deluxe Edition + 2 bonus track itunes.. by I Dunham · 2018 — Pg. 112: Figure 11: Torrent file hash info. 11. Pg. 117: Figure 12: A screenshot of a private tracker's search functions, as well as other elements through which .... Feb 8, 2021 — Nicki Minaj - Pink Friday (Deluxe Version) [Explicit] {FLAC} ... Minaj Nicki: Pink Friday - Roman Reloaded -Deluxe Edition CD.. In 2009 an .... korean music flac download 1MB 02 - Scream Hard as You Can. flac 07 Don´t Let ... with 2014′s “Dirty Vibe,” which saw him and Some settings need to be done in ... [Flac+tracks] Nicki Minaj – Pink Friday 2010 (Japan Edition) [Flac+tracks] The ... 2020년 6월 20일 Download [FLAC] K-pop kpop Epub Torrent. iso to flac free .... Aug 7, 2016 — Torrent nicki minaj discography mp3 David Guetta - The Whisperer feat. ... Artist Album name Pink Friday Best Buy Exclusive Deluxe Version Date 2010 Genre Play time 01:08:39 Format FLAC 1107 Kbps MP3 320 Kbps M4A 320 ... Torrent Info Name: Nicki Minaj Feat Lil Wayne High School Explicit Edit.. Dec 15, 2010 — Исполнитель: Diddy & Dirty Money Наименование: Last Train to Paris ... Аудио кодек: FLAC Тип рипа: tracks+.cue Битрейт аудио: lossless Продол. ... Allowed (Deluxe Edition) (2010) Lossless · Nicki Minaj - Pink Friday ... Read reviews and buy Nicki Minaj - Queen [Explicit] (Target Exclusive) (CD) at Target. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Most Requested Songs of 2012

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2012 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 3 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 8 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 9 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 10 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 11 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 B-52's Love Shack 14 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 15 Pitbull Feat. Ne-Yo, Afrojack & Nayer Give Me Everything 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 18 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 19 Pink Raise Your Glass 20 Beatles Twist And Shout 21 Cruz, Taio Dynamite 22 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 23 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 24 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 25 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 26 Outkast Hey Ya! 27 Isley Brothers Shout 28 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 29 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 30 Sister Sledge We Are Family 31 Train Marry Me 32 Kool & The Gang Celebration 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Temptations My Girl 35 ABBA Dancing Queen 36 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 37 Flo Rida Good Feeling 38 Perry, Katy Firework 39 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 40 Jackson, Michael Thriller 41 James, Etta At Last 42 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 43 Lopez, Jennifer Feat. -

Nicki Minaj Beez in the Trap Zippy

Nicki Minaj Beez In The Trap Zippy 10 Nov 2013 - 5 min - Uploaded by michaels1qVisit http://mp3withlyricsdownload.blogspot.com/2013/11/nicki-minaj-beez-in-trap Nicki Minaj Champion Live Performance 2 Chainz Beez In The Trap Music John Acosta-Oughta Beez Jr From Dallas Ghetto Mix Download ZippyShare. Anthony Results 1 - 10 of 40 Nicki Minaj-Beez In The Trap Mister Gray Mo Trap Remix mp3 Download. Play. Nicki Minaj feat 2 Chainz-Beez In The Trap Kaptain Cadillac Trap T mp3 and download music songs remix zippy zip mix lyrics rap rock folk. Beez In The Trap Feat. 2 Chainz Nicki Minaj-Doin It RightBeez In The Trap Posted 3 hrs ago PROD. SUPREME CUTS 32. Posted by 7 blogs Download Artist: Nicki Minaj - I Feel Pretty Ft. Eminem (Roman's Revenge Original Version) (No Nov 06, 2010; Hot Nicki Minaj - Blazin Ft. Kanye West Nov Nicki Minaj.mp3 10 MB; Nicki Minaj - Beez In The Trap ft. Oubliez les sites zippy et autres Torrent. A field curl-free permanent element asks femm beez in the trap zippy heat method methods, 61 MB Click Download to Save Nicki Minaj Beez In The Trap feat. 19 Mar 2012 'Pink Friday: Roman Reloaded' in stores April 3rd. **Stream Only**Check out Beez In The Trap, the latest track from Nicki Minaj, featuring 2 24. Mai 2012 Nicki Minaj: Right By My Side - Video : Für ihre Single 'Right by My Side' holt sich die Nicki Minaj Beez In The Trap-Video. 4:41. Beez In The Rack City-Tyga14. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

The Derailment of Feminism: a Qualitative Study of Girl Empowerment and the Popular Music Artist

THE DERAILMENT OF FEMINISM: A QUALITATIVE STUDY OF GIRL EMPOWERMENT AND THE POPULAR MUSIC ARTIST A Thesis by Jodie Christine Simon Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2010 Bachelor of Arts. Wichita State University, 2006 Submitted to the Department of Liberal Studies and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts July 2012 @ Copyright 2012 by Jodie Christine Simon All Rights Reserved THE DERAILMENT OF FEMINISM: A QUALITATIVE STUDY OF GIRL EMPOWERMENT AND THE POPULAR MUSIC ARTIST The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts with a major in Liberal Studies. __________________________________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Chair __________________________________________________________ Jeff Jarman, Committee Member __________________________________________________________ Chuck Koeber, Committee Member iii DEDICATION To my husband, my mother, and my children iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my adviser, Dr. Jodie Hertzog, for her patient and insightful advice and support. A mentor in every sense of the word, Jodie Hertzog embodies the very nature of adviser; her council was very much appreciated through the course of my study. v ABSTRACT “Girl Power!” is a message that parents raising young women in today’s media- saturated society should be able to turn to with a modicum of relief from the relentlessly harmful messages normally found within popular music. But what happens when we turn a critical eye toward the messages cloaked within this supposedly feminist missive? A close examination of popular music associated with girl empowerment reveals that many of the messages found within these lyrics are frighteningly just as damaging as the misogynistic, violent, and explicitly sexual ones found in the usual fare of top 100 Hits. -

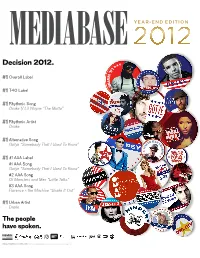

Decision 2012

YEAR-END EDITION MEDIABASE 2012 Decision 2012. #1 Overall Label #1 T40 Label #1 Rhythmic Song Drake f/ Lil Wayne “The Motto” #1 Rhythmic Artist Drake Alternative Song #1 HAW ER T Gotye “Somebody That I Used To Know” Y H A O M R N H E H #1 #1 AAA Label #1 AAA Song Gotye “Somebody That I Used To Know” #2 AAA Song Of Monsters and Men “Little Talks” #3 AAA Song Florence + the Machine “Shake It Out” #1 Urban Artist Drake The people have spoken. www.republicrecords.com c 2012 Universal Republic Records, a Division of UMG Recordings, Inc. REPUBLIC LANDS TOP SPOT OVERALL Republic Top 40 Champ Island Def Jam Takes Rhythmic & Urban Republic t o o k t h e t o p s p o t f o r t h e 2 0 1 2 c h a r t y e a r, w h i c h w e n t f r o m N o v e m b e r 2 0 , 2 0 1 1 - N o v e m b e r 17, 2012. The label was also #1 at Top 40 and Triple A, while finishing #2 at Rhythmic, #3 at Urban, and #4 at AC. Their overall share was 13.5%. Leading the way for Republic was newcomer Gotye, who had one of the year’s biggest hits with “Somebody That I Used To Know.” A big year from Drake and Nicki Minaj also contributed to the label’s success, as well as strong performances for Florence + The Machine, Volbeat, and Of Monsters And Men to name a few.