Holderness: Land Drainage and the Evolution of a Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humberside Police Area

ELECTION OF A POLICE AND CRIME COMMISSIONER for the HUMBERSIDE POLICE AREA - EAST YORKSHIRE VOTING AREA 15 NOVEMBER 2012 The situation of each polling station and the description of voters entitled to vote there, is shown below. POLLING STATIONS Station PERSONS Station PERSONS Station PERSONS numbe POLLING STATION ENTITLED TO numbe POLLING STATION ENTITLED TO numbe POLLING STATION ENTITLED TO r VOTE r VOTE r VOTE 1 21 Main Street (AA) 2 Kilnwick Village Hall (AB) 3 Bishop Burton Village Hall (AC) Main Street 1 - 116 School Lane 1 - 186 Cold Harbour View 1 - 564 Beswick Kilnwick Bishop Burton EAST RIDING OF EAST RIDING OF EAST RIDING OF YORKSHIRE YORKSHIRE YORKSHIRE 4 Cherry Burton Village (AD) 5 Dalton Holme Village (AE) 6 Etton Village Hall (AF) Hall 1 - 1154 Hall 1 - 154 37 Main Street 1 - 231 Main Street West End Etton Cherry Burton South Dalton EAST RIDING OF EAST RIDING OF EAST RIDING OF YORKSHIRE YORKSHIRE YORKSHIRE 7 Leconfield Village Hall (AG) 8 Leven Recreation Hall (AH) 9 Lockington Village Hall (AI) Miles Lane 1 - 1548 East Street 1 - 1993 Chapel Street 1 - 451 Leconfield LEVEN LOCKINGTON EAST RIDING OF YORKSHIRE 10 Lund Village Hall (AJ) 11 Middleton-On-The- (AK) 12 North Newbald Village Hall (AL) 15 North Road 1 - 261 Wolds Reading Room 1 - 686 Westgate 1 - 870 LUND 7 Front Street NORTH NEWBALD MIDDLETON-ON-THE- WOLDS 13 2 Park Farm Cottages (AM) 14 Tickton Village Hall (AN) 15 Walkington Village Hall (AO) Main Road 1 - 96 Main Street 1 - 1324 21 East End 1 - 955 ROUTH TICKTON WALKINGTON 16 Walkington Village Hall (AO) 17 Bempton Village Hall (BA) 18 Boynton Village Hall (BB) 21 East End 956 - 2 St. -

Housing Land Supply Position Statement 2020/21 to 2024/25

www.eastriding.gov.uk www.eastriding.gov.uk ff YouYouTubeTube East Riding Local Plan 2012 - 2029 Housing Land Supply Position Statement For the period 2020/21 to 2024/25 December 2020 Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 1 National Policy .................................................................................................................. 1 Performance ...................................................................................................................... 3 Residual housing requirement ......................................................................................... 5 2 Methodology ........................................................................................................... 7 Developing the Methodology ........................................................................................... 7 Covid-19 ............................................................................................................................. 8 Calculating the Potential Capacity of Sites .................................................................... 9 Pre-build lead-in times ................................................................................................... 10 Build rates for large sites .............................................................................................. -

House Number Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Town/Area County

House Number Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Town/Area County Postcode 64 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 70 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 72 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 74 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 80 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 82 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 84 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 1 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 2 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 3 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 4 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 1 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 3 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 5 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 7 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 9 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 11 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 13 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 15 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 17 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 19 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 21 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 23 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 25 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 -

Barn Cottage, Main Street, Brantingham £450,000 Fabulous Stone and Tiled Construction Village Has a Public House/Restaurant and Has "Karndean' Flooring and Radiator

Barn Cottage, Main Street, Brantingham £450,000 Fabulous stone and tiled construction village has a public house/restaurant and Has "Karndean' flooring and radiator. Leads extended 4 Bedroom Link Detached House communal hall and there are many delightful into: with long landscaped garden located within walks close by including the Wolds Way which SITTING ROOM 17' x 9'9 (5.18m x 2.97m) the heart of this highly regarded village. lies to the west of the village. Local shops, Superb extension with pitched roof and views Viewing highly recommended. schools & sporting facilities can be found at of the rear garden: Has radiator, oak the nearby villages of South Cave, Elloughton INTRODUCTION engineered flooring and french doors leading & Brough, each village being almost Appointed to a high standard, this delightful to a delightful paved patio. equidistant and approximately five minutes property is situated on Main Street within by car. A main line rail station is located at KITCHEN 14'2 x 8'4 (4.32m x 2.54m) view of the village pond. The rear garden Brough with direct links to Hull & London This well fitted kitchen offers a offers fabulous views of the surrounding Kings Cross. comprehensive range of cream high gloss countryside. The accommodation comprises fronted floor and wall units complimented by Entrance Hall with Cloak/WC off, Living Room, ENTRANCE HALL solid wood work surfaces and integrated Dining Room, rear Sitting Room extension With uPVC door and glazed screen, radiator. dishwasher; plumbed for washing machine; with garden views and a spacious modern CLOAKROOM 1.5 bowl sink unit; ceramic tiled floor; radiator. -

The EYMS Mobile App! Service 130 Buses Now Track Your Bus!

New: Mon 3 Sept 2018. Bridlington : Fraisthorpe : Skipsea : North Frodingham : Driffield 136 Monday to Saturday a.m. a.m. a.m. p.m. p.m. p.m. Now track Bridlington (Bus Station) .......... - 8 30 1130 2 30 5 00 6 15 Shaftesbury Road/Kingsgate...... - 8 37 1137 2 37 5 07 6 22 your bus! Avocet Way ................................ - - - - 5 08 6 23 Got a smart phone? South Shore Holiday Village ....... - 8 41 1141 2 41 5 11 6 26 Visit www.eyms.co.uk to get Fraisthorpe Lane End ................. - 8 44 1144 2 44 5 14 6 29 a live countdown to when Barmston (Black Bull Pub).......... - 8 47 1147 2 47 5 17 6 32 your bus will arrive. Lissett....................................... - 8 51 1151 2 51 5 21 6 36 Drop-off only Ulrome (Church) ........................ - 8 55 1155 2 55 5 25 6 40 Ulrome (Coastguard Cottages) ... - 8 58 1158 2 58 5 28 6 43 After Fraisthorpe, these Skipsea Village .......................... - 9 06 1206 3 06 5 36 6 51 journeys are for passenger Skipsea Sands Holiday Park ....... - 9 08 1208 3 08 5 38 6 53 drop-off only. Beeford (Post Office) .................. 7 00 9 18 1218 3 18 5 48 7 03 North Frodingham (Post Office)... 7 05 9 23 1223 3 23 5 53 7 08 Wansford ................................... 7 10 9 30 1230 3 30 - - Driffield (George Street) ........... 7 19 9 39 1239 3 39 - - No Sunday Buses Service 130 buses For additional buses between Skipsea and Bridlington, pick-up a Service 130 leaflet. Driffield : North Frodingham : Skipsea : Fraisthorpe : Bridlington 136 Monday to Saturday The EYMS a.m. -

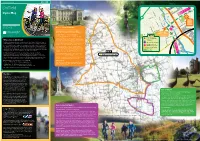

Driffield EASTFIELD

A614 www.eastriding.gov.uk AD RO TMENT LANE ALLO Driffield EASTFIELD SCARBOR A614 SPELLO AD RO ON THE TOWARDS NAFFERTON WGAT OUGH RO AV - follow for rides 1, 4 and 5 Cycle Map TH ST BRIDLINGT GIBSON ST E NOR NUE PARK CLOSE E WEST GA AD AD YORK RO MANORFIELD EA TE S MIDDLE ST N T GA EAST VICT AD TE RO B1249 RIDING AVE ORIA N NEW WEST GA LEISURE AD ST RO EAST GA DRIFFIELD AD Five cycle routes in and NEWLAND TE TE WANSFORDMANORFIELD RO RO around Driffield Ride 3 – CHALLENGING EXCHANGE S MILL ST T Some long climbs, which are worth it for the AVE AD DUNN’S LN beautiful views from the top of the Wolds. KINGS MILL RO QUEEN S AD AD RO CUSTOMER OW An excellent day ride for confident family groups. KING ST SESERRVVICESI CENTRE MEAD 32 miles / 52km, or 4 hours riding time. /LIB/LIBRARY/WC ALBION ST KEY MIDDLE ST S BRA BRA Leave Driffield along NCN route 1 travelling south along BRA Skerne Road. After approximately 3.5 miles, turn right at SECURE CYCLE PARKING B1 CKEN E CK CKEN LOCKWOOD ST 2 49 the crossroads towards Hutton. When you reach the village ST JOHN’S RO Welcome to Driffield! CYCLE SHON P RIVER HEAD continue past the phone box and turn right towards Southburn. R RO O RI Pass over the junction with the A164 and at the T junction ADA Driffield is a charming market town situated to the east of the Yorkshire Wolds approximately FREE LONG STAY CAR PARKING VERSID TOWARDS SKERNE 12 miles inland from the North Sea coast. -

List of Appointments to Outside Bodies 2021/22

EAST RIDING OF YORKSHIRE COUNCIL List of appointments to Outside Bodies 2021/22 NB -All appointments are made at the Council AGM for the period of the municipal year unless otherwise stated. National, Regional and Sub-Regional Organisations Outside Body Representatives CATCH Board Cllr Evison County Councils Network Cllr Owen Cllr Holtby Cllr Aitken Cllr V Walker Hull & East Riding Unitary Leaders’ Board Cllr Owen Cllr Holtby Humber Coast and Vale Chairs and Members Group Cllr V Walker Humber Leadership Board Cllr Owen Cllr Holtby Humber Strategy Comprehensive Review Elected Members Cllr Matthews Forum Humber Teaching NHS Foundation Trust – Council of Cllr Wilkinson Governors Humberside Crimestoppers Cllr Padden Humberside Fire Authority Cllr Chadwick Cllr Dennis Cllr Fox Cllr Green Cllr Healing Cllr Smith Cllr Davison Cllr Jefferson LEP - Hull & East Yorkshire LEP Board Cllr Owen - Sub-Boards to be confirmed Local Government Association Cllr Owen Cllr Holtby Cllr Lee Cllr Nolan (observer) - Coastal Special Interest Group Cllr Matthews - Rural Services Network Cllr Evison v1_FINAL 07/07/21 WEB Outside Body Representatives North Eastern IFCA Cllr Matthews Cllr Copsey Northern Lincolnshire and Goole NHS Foundation Trust Vacancy Council of Governors Police and Crime Panel Cllr Gateshill Cllr Nickerson Cllr Abraham Substitutes - Cllr Weeks/Cllr Birch Rail North Committee Cllr McMaster Reserved Forces and Cadets Association for Yorkshire and Cllr Elvidge the Humber Cllr Wilkinson SWAP Internal Audit Partnership Members’ Board Cllr Temple Substitute -

Lissett Community Wind Farm Fund Annual Report | April 2011 - March 2012

Lissett Community Wind Farm Fund Annual Report | April 2011 - March 2012 Infinis is one of the country’s leading renewable energy Fund Criteria producers and the operating company responsible for the The criteria for grant applications is ‘public benefit’ and Lissett Community Wind Farm. As part of the development’s community groups, organisations and parish councils applying planning permission, granted in 2007 a commitment was made for grants must show how the project for which they are asking by the developers within to create a community fund. for money will be of benefit to the public. The fund, Lissett Community Wind Farm Fund receives an Annual Donation from Infinis of £2,000 per megawatt of Public Benefit can be a difficult concept to define and installed operating capacity of the wind farm to a maximum of can be broadly interpreted. As a guide the charity £60,000 per annum. The first donation of £53,360 was paid commission recommends that: into the fund in January 2010, ten months after the wind farm • The benefits of a project are demonstrable began exporting electricity to the national grid and since that • The activity must be open to all of the public or a time has received two further donations of £60,000 each have section of the public been received. The Infinis total donation of £173,360 has been The Lissett Community Wind Farm Fund panel asks received to date. for reports which give details and evidence of activities undertaken using the money awarded. Fund Aims The Lissett Community Wind Farm Fund panel looks The aim of the fund is to provide grants to community groups at applications to ensure that activities are open to all and organisations and parish councils in the East Wolds and members of the community. -

Ellerker Enclosure Award - 1766

Ellerker Enclosure Award - 1766 Skinn 1 TO ALL TO WHOM THESE PRESENTS SHALL COME John Cleaver of Castle Howard in the County of York gentleman John Dickinson of Beverley in the said County of York Gentleman and John Outram of Burton Agnes in the said County of York Gentleman Give Greeting WHEREAS by an Act of Parliament in the fifth year of the reign of his Gracious Majesty King George the Third ENTITLED An Act for Dividing and Inclosing certain Open Commons Lands Fields and Grounds in the Township of Ellerker in the Parish of Brantingham in the East Riding of the County of York RECITING that the Township of Ellerker in the Parish of Brantingham in the east Riding of the County of York consists of Seventy Five oxgangs of Land and some odd Lands and also Fifty Two Copyhold and Freehold ancient Common Right Houses and Frontsteads and of certain parcels of Ground belonging to the said Common Right Houses and Frontsteads called Norfolk Acres the Dams the Common Ings Rees Plumpton Parks and the Flothers with several oxgangs of Land and odd lands and pieces or parcels of Ground lying in the open Common Fields and open Common Pastures and Meadow Grounds twelve of which oxgangs Are Freehold and Sixty Three of them are Copyhold of the Bishop of Durham of his Manor of Howden Twenty Four of which Copyhold oxgangs are Hall Lands and are lying in the Hall Fields and in the Hall Ings and the remaining Thirty Four Copyhold oxgangs and the said Twelve Freehold oxgangs and the said odd lands are called Town Lands and are lying in the Town Fields and in -

River Hull Integrated Catchment Strategy Strategy Document

River Hull Advisory Board River Hull Integrated Catchment Strategy April 2015 Strategy Document Draft report This Page is intentionally left blank 2 Inner Leaf TITLE PAGE 3 This page is intentionally left blank 4 Contents 1 This Document.............................................................................................................................17 2 Executive Summary ..............................................................................................................18 3 Introduction and background to the strategy ..................................20 3.1 Project Summary .................................................................................................................................... 20 3.2 Strategy Vision ........................................................................................................................................ 20 3.2.1 Links to other policies and strategies .......................................................................................21 3.3 Background .............................................................................................................................................. 22 3.3.1 Location ........................................................................................................................................... 22 3.3.2 Key characteristics and issues of the River Hull catchment ...............................................22 3.3.3 EA Draft River Hull Flood Risk Management Strategy .........................................................26 -

ERN Nov 2009.Indb

WINNER OF THE GOOD COMMUNICATIONS AWARD 2008 FOR JOURNALISM EAST RIDING If undelivered please return to HG115, East Riding of Yorkshire Council, County Hall, Cross Street, Beverley, HU17 9BA Advertisement Feature At Last! A NEW FORM OF HEATING FROM GERMANY… NEWS Simple to install, Powerful, Economical, and no more servicing – EVER! n Germany & Austria more and are making that same decision! When more people are choosing to you see this incredible heating for NOVEMBER 2009 EDITION Iheat their homes and offices with yourself, you could be next! a very special form of electric Discover for yourself this incredible • FREE TO YOU heating in preference to gas, oil, lpg heating from Germany. Get your or any other form of conventional info pack right away by calling • PAID FOR BY central heating. Here in the UK Elti Heating on Bridlington ADVERTISING more and more of our customers 01262 677579. New ‘destination’ playpark one of best in East Riding IN THIS ISSUE BACKING THE BID Help us bring the World Cup to East Yorkshire PAGE 28 WIN A WEDDING Win your perfect day with a Heritage Coast wedding PAGE 23 WIN A CRUSHER ENCOURAGING MORE CHILDREN TO PLAY OUT: Councillor Chris Matthews, chairman of the council, Win a free crusher in our blue bins draw opens the new playpark at Haltemprice Leisure Centre, with local schoolchildren and Nippy the kangaroo to help you wash and squash PAGE 9 EXCITING NEW PLAYPARK OPENS BY Tom Du Boulay best facilities in the East Riding by £200,000 from the Department protection, said: “The new and gives children and young for Children, Schools and Families playpark is a state-of-the-art E. -

CITY of HULL AC NEWSLETTER OCTOBER 2004 ***Christmas Party

CITY OF HULL AC NEWSLETTER OCTOBER 2004 ***Christmas Party*** *Triton Inn, Brantingham, Saturday, 11th December* *5 Course Christmas Menu* *Bar & Disco, Cost £21.50 per Person* *£5.00 Deposit by 20th November 2004* *We have just 68 places only, for what should be a great night,* *so, if you are interested see Carol Ingleston,* *or telephone her on 07766 540563. Book early to avoid disappointment* Training Sessions Monday 5.45pm Humber Bridge top car park Speed session Tuesday 7.00pm From Haltemprice Sports Centre Club night Thursday 9.00am Elloughton Dale top Pensioner’s Plod Thursday 6.00pm From Haltemprice Sports Centre Club night Thursday 700pm From Haltemprice Sports Centre Fartlek Session Saturday 8.30am Wauldby Green, Raywell 3 to 5 mile cross country Sunday 8.45am Brantingham Dale car park half way down Cross country City of Hull 3 Mile Winter League Series - all start at 7.15pm Tue 9th Nov Humber Bridge top car park Tue 14th Dec as above Tue 11th Jan as above Tue 1st Feb as above Tue 1st Mar as above The first race of this series was held on 12th October and attracted 61 runners. This was not a problem at the finish due to there being no handicap times. However, for future races, we could possibly get 61 plus runners all coming through the finish line at the same time. So, could I please ask you to stay in line in the funnel, do not pass the person in front of you and display your number clearly for the markers. If anything does go wrong at the finish with the recording of the times and numbers, please remember, that our finishing crew are all volunteers, who do an excellent job.