Promoting Healthier Weight in Pediatrics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aussie Classics Hits - 180 Songs

Available from Karaoke Home Entertainment Australia and New Zealand Aussie Classics Hits - 180 Songs 1 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc 2 Absolutely Everybody Vanessa Amorosi 3 Age Of Reason John Farnham 4 All I Do Daryl Braithwaite 5 All My Friends Are Getting Married Skyhooks 6 Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again The Angels 7 Amazing Alex Lloyd 8 Amazing Vanessa Amorosi 9 Animal Song Savage Garden 10 April Sun In Cuba Dragon 11 Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jet 12 Art Of Love Guy Sebastian, Jordin Sparks 13 Aussie Rules I Thank You For The Best Kevin Johnson Years Of Our Lives 14 Australian Boy Lee Kernaghan 15 Barbados The Models 16 Battle Scars Guy Sebastian, Lupe Fiasco 17 Bedroom Eyes Kate Ceberano 18 Before The Devil Knows You're Dead Jimmy Barnes 19 Before Too Long Paul Kelly, The Coloured Girls 20 Better Be Home Soon Crowded House 21 Better Than John Butler Trio 22 Big Mistake Natalie Imbruglia 23 Black Betty Spiderbait 24 Bluebird Kasey Chambers 25 Bopping The Blues Blackfeather 26 Born A Woman Judy Stone 27 Born To Try Delta Goodrem 28 Bow River Cold Chisel 29 Boys Will Be Boys Choir Boys 30 Breakfast At Sweethearts Cold Chisel 31 Burn For You John Farnham 32 Buses And Trains Bachelor Girl 33 Chained To The Wheel Black Sorrows 34 Cheap Wine Cold Chisel 35 Come On Aussie Come On Shannon Noll 36 Come Said The Boy Mondo Rock 37 Compulsory Hero 1927 38 Cool World Mondo Rock 39 Crazy Icehouse 40 Cry In Shame Johnny Diesel, The Injectors 41 Dancing With A Broken Heart Delta Goodrem 42 Devil Inside Inxs 43 Do It With Madonna The Androids 44 -

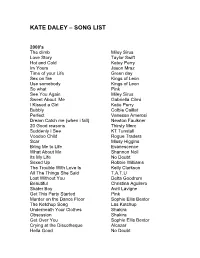

Kate Daley – Song List

KATE DALEY – SONG LIST 2000's The climb Miley Sirus Love Story Taylor Swift Hot and Cold Katey Perry Im Yours Jason Mraz Time of your Life Green day Sex on fire Kings of Leon Use somebody Kings of Leon So what Pink See You Again Miley Sirus Sweet About Me Gabriella Cilmi I Kissed a Girl Katie Perry Bubbly Colbie Caillat Perfect Vanessa Amerosi Dream Catch me (when i fall) Newton Faulkner 20 Good reasons Thirsty Merc Suddenly I See KT Tunstall Voodoo Child Rogue Traders Scar Missy Higgins Bring Me to Life Evanescence What About Me Shannon Noll Its My Life No Doubt Sexed Up Robbie Williams The Trouble With Love Is Kelly Clarkson All The Things She Said T.A.T.U Lost Without You Delta Goodrem Beautiful Christina Aguilero Skater Boy Avril Lavigne Get This Party Started Pink Murder on the Dance Floor Sophie Ellis Bextor The Ketchup Song Las Ketchup Underneath Your Clothes Shakira Obsession Shakira Get Over You Sophie Ellis Bextor Crying at the Discotheque Alcazar Hella Good No Doubt Lets Get Loud Jennifer Lopez Don’t Stop Moving S Club 7 Cant Get you Out of My Head Kylie Minogue I’m Like a Bird Nelly Fertado Absolutely Everybody Vanessa Amorosi Fallin’ Alicia Keys I Need Somebody Bardot Lady marmalade Moulin Rouge Drops of Jupiter Train Out of Reach Gabrielle (Bridgett Jones Dairy) Hit em up in Style Blu Cantrell Breathless The Corrs Buses and trains Bachelor Girl Shine Vanessa Amorosi What took you so long Emma B Overload Sugarbabes Cant Fight the Moonlight Leeann Rhymes (Coyote Ugly) Sunshine on a Rainy Day Christine Anu On a Night Like This -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION -

Use Somebody Kings of Leon Reckless Australian

MARTY & DOC SONGLIST Use Somebody Kings of Leon Reckless Australian Crawl Mr Brightside The Killers These Days Powderfinger Riders in the Storm The Doors 3am Matchbox 20 Sex On Fire Kings of Leon Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers The Way You Make Me Feel Michael Jackson All I Want Is You U2 Sweet about me Gabriela Cilmi Crying shame Diesel Rehab Amy Winehouse Times like these Foo Fighters Shake a Tailfeather Ray Charles Hold back the river James Bay Wicked Games Chris Isaac Easy Faith No More Happy Pharrell Williams Faith George Michael Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Heroes David Bowie Raspberry Berre Prince Drive My Car The Beatles Stand By Me Ben E King Its still rocking roll to me Billy Joel Hide your love away The Beatles Hot in the city Billy Idol Locked out of heaven Bruno Mars Girls just wanna have fun Cyndi Lauper April Sun In Cuba Dragon Handle With Care Travelling Wilbury’s Summer Of 69 Bryan Adams Have You Ever Seen The Rain Creedence Clearwater Revival Rolling in the Deep Adele Dancing In The Dark Bruce Springsteen Love Destroyer Leeden Don't Look Back In Anger Oasis Proud Mary Creedence Clearwater Revival Don’t Change INXS Wandering Leeden April Sun In Cuba Dragon Hold Your Own Leeden Better Be Home Soon Crowded House Go Your Own Way Fleetwood Mac Bittersweet Symphony The Verve Steal My Kisses Ben Harper Blame It On Me George Ezra Valerie Amy Winehouse Champagne Supernova Oasis Nobody needs to know Leeden Come Together The Beatles Plush Stone Temple Pilots Honky Tonk Woman The Rolling Stones Never Tear Us Apart INXS Horses Darryl -

Songs by Artist

DJU Karaoke Songs by Artist Title Versions Title Versions ! 112 Alan Jackson Life Keeps Bringin' Me Down Cupid Lovin' Her Was Easier (Than Anything I'll Ever Dance With Me Do Its Over Now +44 Peaches & Cream When Your Heart Stops Beating Right Here For You 1 Block Radius U Already Know You Got Me 112 Ft Ludacris 1 Fine Day Hot & Wet For The 1st Time 112 Ft Super Cat 1 Flew South Na Na Na My Kind Of Beautiful 12 Gauge 1 Night Only Dunkie Butt Just For Tonight 12 Stones 1 Republic Crash Mercy We Are One Say (All I Need) 18 Visions Stop & Stare Victim 1 True Voice 1910 Fruitgum Co After Your Gone Simon Says Sacred Trust 1927 1 Way Compulsory Hero Cutie Pie If I Could 1 Way Ride Thats When I Think Of You Painted Perfect 1975 10 000 Maniacs Chocol - Because The Night Chocolate Candy Everybody Wants City Like The Weather Love Me More Than This Sound These Are Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH 10 Cc 1st Class Donna Beach Baby Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz Good Morning Judge I'm Different (Clean) Im Mandy 2 Chainz & Pharrell Im Not In Love Feds Watching (Expli Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz And Drake The Things We Do For Love No Lie (Clean) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Chainz Feat. Kanye West 10 Years Birthday Song (Explicit) Beautiful 2 Evisa Through The Iris Oh La La La Wasteland 2 Live Crew 10 Years After Do Wah Diddy Diddy Id Love To Change The World 2 Pac 101 Dalmations California Love Cruella De Vil Changes 110 Dear Mama Rapture How Do You Want It 112 So Many Tears Song List Generator® Printed 2018-03-04 Page 1 of 442 Licensed to Lz0 DJU Karaoke Songs by Artist -

Redox DAS Artist List for Period: 01.10.2017

Page: 1 Redox D.A.S. Artist List for period: 01.10.2017 - 31.10.2017 Date time: Number: Title: Artist: Publisher Lang: 01.10.2017 00:02:40 HD 60753 TWO GHOSTS HARRY STYLES ANG 01.10.2017 00:06:22 HD 05631 BANKS OF THE OHIO OLIVIA NEWTON JOHN ANG 01.10.2017 00:09:34 HD 60294 BITE MY TONGUE THE BEACH ANG 01.10.2017 00:13:16 HD 26897 BORN TO RUN SUZY QUATRO ANG 01.10.2017 00:18:12 HD 56309 CIAO CIAO KATARINA MALA SLO 01.10.2017 00:20:55 HD 34821 OCEAN DRIVE LIGHTHOUSE FAMILY ANG 01.10.2017 00:24:41 HD 08562 NISEM JAZ SLAVKO IVANCIC SLO 01.10.2017 00:28:29 HD 59945 LEPE BESEDE PROTEUS SLO 01.10.2017 00:31:20 HD 03206 BLAME IT ON THE WEATHERMAN B WITCHED ANG 01.10.2017 00:34:52 HD 16013 OD TU NAPREJ NAVDIH TABU SLO 01.10.2017 00:38:14 HD 06982 I´M EVERY WOMAN WHITNEY HOUSTON ANG 01.10.2017 00:43:05 HD 05890 CRAZY LITTLE THING CALLED LOVE QUEEN ANG 01.10.2017 00:45:37 HD 57523 WHEN I WAS A BOY JEFF LYNNE (ELO) ANG 01.10.2017 00:48:46 HD 60269 MESTO (FEAT. VESNA ZORNIK) BREST SLO 01.10.2017 00:52:21 HD 06008 DEEPLY DIPPY RIGHT SAID FRED ANG 01.10.2017 00:55:35 HD 06012 UNCHAINED MELODY RIGHTEOUS BROTHERS ANG 01.10.2017 00:59:10 HD 60959 OKNA ORLEK SLO 01.10.2017 01:03:56 HD 59941 SAY SOMETHING LOVING THE XX ANG 01.10.2017 01:07:51 HD 15174 REAL GOOD LOOKING BOY THE WHO ANG 01.10.2017 01:13:37 HD 59654 RECI MI DA MANOUCHE SLO 01.10.2017 01:16:47 HD 60502 SE PREPOZNAS SHEBY SLO 01.10.2017 01:20:35 HD 06413 MARGUERITA TIME STATUS QUO ANG 01.10.2017 01:23:52 HD 06388 MAMA SPICE GIRLS ANG 01.10.2017 01:27:25 HD 02680 HIGHER GROUND ERIC CLAPTON ANG 01.10.2017 01:31:20 HD 59929 NE POZABI, DA SI LEPA LUKA SESEK & PROPER SLO 01.10.2017 01:34:57 HD 02131 BONNIE & CLYDE JAY-Z FEAT. -

ADJS Top 200 Song Lists.Xlsx

The Top 200 Australian Songs Rank Title Artist 1 Need You Tonight INXS 2 Beds Are Burning Midnight Oil 3 Khe Sanh Cold Chisel 4 Holy Grail Hunter & Collectors 5 Down Under Men at Work 6 These Days Powderfinger 7 Come Said The Boy Mondo Rock 8 You're The Voice John Farnham 9 Eagle Rock Daddy Cool 10 Friday On My Mind The Easybeats 11 Living In The 70's Skyhooks 12 Dumb Things Paul Kelly 13 Sounds of Then (This Is Australia) GANGgajang 14 Baby I Got You On My Mind Powderfinger 15 I Honestly Love You Olivia Newton-John 16 Reckless Australian Crawl 17 Where the Wild Roses Grow (Feat. Kylie Minogue) Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds 18 Great Southern Land Icehouse 19 Heavy Heart You Am I 20 Throw Your Arms Around Me Hunters & Collectors 21 Are You Gonna Be My Girl JET 22 My Happiness Powderfinger 23 Straight Lines Silverchair 24 Black Fingernails, Red Wine Eskimo Joe 25 4ever The Veronicas 26 Can't Get You Out Of My Head Kylie Minogue 27 Walking On A Dream Empire Of The Sun 28 Sweet Disposition The Temper Trap 29 Somebody That I Used To Know Gotye 30 Zebra John Butler Trio 31 Born To Try Delta Goodrem 32 So Beautiful Pete Murray 33 Love At First Sight Kylie Minogue 34 Never Tear Us Apart INXS 35 Big Jet Plane Angus & Julia Stone 36 All I Want Sarah Blasko 37 Amazing Alex Lloyd 38 Ana's Song (Open Fire) Silverchair 39 Great Wall Boom Crash Opera 40 Woman Wolfmother 41 Black Betty Spiderbait 42 Chemical Heart Grinspoon 43 By My Side INXS 44 One Said To The Other The Living End 45 Plastic Loveless Letters Magic Dirt 46 What's My Scene The Hoodoo Gurus -

ARIA TOP 50 AUSTRALIAN ARTIST SINGLES CHART 2008 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS <D> DIAMOND UNITS TY THIS YEAR ARIA TOP 50 AUSTRALIAN ARTIST SINGLES CHART 2008 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO. 1 SWEET ABOUT ME Gabriella Cilmi <P> MSH/WAR 5144262642 2 UNTOUCHED The Veronicas <P> WARNER 9362498882 3 BLACK AND GOLD Sam Sparro <P> ISL/UMA 1768362 4 RUNNING BACK Jessica Mauboy Feat. Flo Rida <P>2 SBME 88697411792 5 PERFECT Vanessa Amorosi <P> UMA 1763772 6 DON'T HOLD BACK The Potbelleez <P> MOS/UMA VG12063CD 7 MY PEOPLE The Presets <P> MOD/UMA 1760932 8 YOU Wes Carr <P> SBME 88697436702 9 THIS HEART ATTACK Faker <P> CAP/EMI 5097082 10 WHITE NOISE The Living End <G> DEW/UMA DEW900073 11 TAKE ME ON THE FLOOR The Veronicas <G> WARNER US-WB1-07-04606 12 THIS LOVE The Veronicas <G> WARNER 9362498706 13 WALKING ON A DREAM Empire Of The Sun CAP/EMI 2349372 14 I NEVER LIKED YOU Rogue Traders <G> COL/SBME 88697212382 15 I DON'T DO SURPRISES Axle Whitehead <G> ROA/SBME 301439-2 16 THIS BOY'S IN LOVE The Presets <G> MOD/UMA MODCDS052 17 NAUGHTY GIRL Mr G <G> VIR/EMI 2135032 18 ARE YOU WITH ME The Potbelleez VIC/UMA VG12088CD 19 ALIVE Natalie Bassingthwaighte <G> SBME 88697420212 20 TALK LIKE THAT The Presets MOD/UMA MODCDS060 21 KANSAS CITY Sneaky Sound System <G> WHA/MGM WHACK08 22 HOOK ME UP The Veronicas <P> WARNER 9362499180 23 BELIEVE AGAIN Delta <G> SBME 88697214112 24 DON'T WANNA GO TO BED NOW Gabriella Cilmi MSH/WAR 5144290542 25 UFO Sneaky Sound System <P> WHA/MGM WHACK06 26 STRAIGHT LINES Silverchair <P>2 11/UMA ELEVENCD62 27 BURN Jessica Mauboy SBME 88697436282 -

Karaoke Songs We Can Use As at 22 April 2013

Uploaded 3rd May 2013 Before selecting your song - please ensure you have the latest SongBook from the Maori Television Website. TKS No. SONG TITLE IN THE STYLE OF 21273 Don't Tread On Me 311 25202 First Straw 311 15937 Hey You 311 1325 Where My Girls At? 702 25858 Til The Casket Drops 16523 Bye Bye Baby Bay City Rollers 10657 Amish Paradise "Weird" Al Yankovic 10188 Eat It "Weird" Al Yankovic 10196 Like A Surgeon "Weird" Al Yankovic 18539 Donna 10 C C 1841 Dreadlock Holiday 10 C C 16611 I'm Not In Love 10 C C 17997 Rubber Bullets 10 C C 18536 The Things We Do For Love 10 C C 1811 Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs 24657 Hot And Wet 112/ Ludacris 21399 We Are One 12 Stones 19015 Simon Says 1910 Fruitgum Company 26221 Countdown 2 Chainz/ Chris Brown 15755 You Know Me 2 Pistols & R Jay 25644 She Got It 2 Pistols/ T Pain/ Tay Dizm 15462 Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down 23044 Everytime You Go 3 Doors Down 24923 Here By Me 3 Doors Down 24796 Here Without You 3 Doors Down 15921 It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down 15820 Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down 25232 Let Me Go 3 Doors Down 22933 When You're Young 3 Doors Down 15455 Don't Trust Me 3 Oh!3 21497 Double Vision 3 Oh!3 15940 StarStrukk 3 Oh!3 21392 My First Kiss 3 Oh!3 / Ke$ha 23265 Follow Me Down 3 Oh!3/ Neon Hitch 20734 Starstrukk 3 Oh3!/ Katy Perry 10816 If I'd Been The One 38 Special 10112 What's Up 4 Non Blondes 9628 Sukiyaki 4.pm 15061 Amusement Park 50 Cent 24699 Candy Shop 50 Cent 12623 Candy Shop 50 Cent 1 Uploaded 3rd May 2013 Before selecting your song - please ensure you have the latest SongBook from the Maori Television Website. -

Rachel Laing Song List - Updated 28 02 2019

RACHEL LAING SONG LIST - UPDATED 28 02 2019 SONG TITLE ORIGINAL ARTIST VERSION (IF NOT ORIGINAL) 3AM MATCHBOX 20 100 YEARS FIVE FOR FIGHTING 500 MILES (I'M GONNA BE) THE PROCLAIMERS 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ A HORSE WITH NO NAME AMERICA A THOUSAND MILES VANESSA CARLTON A THOUSAND YEARS CHRISTINA PERRI A WHITE SPORTS COAT MARTY ROBBINS ABOVE GROUND NORAH JONES ADORN MIGUEL ADVANCE AUSTRALIA FAIR NATIONAL ANTHEM AHEAD OF MYSELF JAMIE LAWSON AINT NO SUNSHINE BILL WITHERS ALIVE SIA ALL ABOUT THAT BASS MEGHAN TRAINOR ALL OF ME JOHN LEGEND ALL THE SMALL THINGS BLINK 182 ALL TIME LOW JOHN BELLION ANDY GRAMMER ALWAYS ON MY MIND ELVIS AM I EVER GONNA SEE YOUR FACE AGAIN THE ANGELS RACHEL LAING AM I NOT PRETTY ENOUGH KASEY CHAMBERS AM I WRONG NICO & VINZ AMAZING GRACE AND THE BOYS ANGUS & JULIA STONE ANGEL SARAH MCLAUGHLAN ANGELS ROBBIE WILLIAMS ANNIES SONG JOHN DENVER ANOTHER DAY IN PARADISE PHIL COLLINS APOLOGIZE ONE REPUBLIC APRIL SUN IN CUBA DRAGON ARE YOU GONNA BE MY GIRL JET ARE YOU OLD ENOUGH DRAGON ARMY OF TWO OLLY MURS AT LAST ETTA JAMES AULD LANG SYNE AUTUMN LEAVES NAT KING COLE EVA CASSIDY BABY CAN I HOLD YOU TRACEY CHAPMAN BACK TO DECEMBER TAYLOR SWIFT BAD MOON RISING CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL BAIL ME OUT PETE MURRAY BASKET CASE SARA BARELLIS BE HERE TO LOVE ME NORAH JONES BE MY SOMEBODY NORAH JONES BEAUTIFUL IN MY EYES JOSHUA KADISON BESEME MUCHO BEST FRIENDS BRANDY BETTE DAVIS EYES KIM CARNES BETTER BE HOME SOON CROWDED HOUSE BETTER MAN PEARL JAM BETTER THAN JOHN BUTLER TRIO BIG DEAL LEANNE RIMES BIG JET PLANE ANGUS & JULIA STONE -

Poco Loco Song List Newly Added Music Classic Pop / Dance

Poco Loco Song List Newly added Music Just the way you are - Bruno Mars Break even - The Script Closer - Chris Brown Love Story - Taylor Swift Forget you - Cee Lo Green Cry for you - September Pack up - Eliza Doolittle The boy does nothing - Alesha Dixon OMG - Usher Mercy - Duffy I've got a feeling - Black eyed Peas Rain - Dragon Bad Romance - Lady Ga Ga Dakota - Stereophonics Poker face - Lady Ga Ga California Gurls - Katy Perry Alejandro - Lady Ga Ga Don't hold Back - Pot Beleez I'm yours - Jason Mraz Sex on Fire - Kings of Leon Hey Soul Sister - Train Like it like that - Guy Sebastian Escape(The Pina Colada Song Smile - Uncle Kracker Sweet about me - Gabriella Cilma Save the lies - Gabriella Cilmi Apologize - One Republic Black and Gold - Sam Sparro Classic Pop / Dance A little less conversation - Elvis Let's dance - Chris Rea Addicted to Bass - Amiel Let's get the party started - Pink Ain't nobody - Chaka Khan Let's groove tonight - Earth wind n fire All I wanna do - Sheryl Crow Lets hear it for the boy - Denise Williams Amazing - George Michael Let's stick together - Bryan Ferry Angels - Robbie Williams Life is a rollercoaster - Ronan Keating Another Saturday night - Sam Cook Love at first sight - Kylie Minogue Around the the world - Lisa Stanfield Love fool - Cardigans Baby did a bad bad thing - Chris Isaac Love foolosophy - Jamiroquai Bad girls - Donna Summer love is in the air - John Paul Young Beautiful - Disco Montego Love really hurts without you - Billy Ocean Believe - Cher Love shack - B52's Bette Davis eyes - Kim Carnes -

La Fiesta Song List 2015

Just Added Song List 2015 SONG NAME ARTIST LIKE? SONG NAME ARTIST LIKE? All About That Bass Meghan Trainor Love Runs Out One Republic Black Widow Iggy Azalea Outside Calvin Harris Blame Calvin Harris Rather Be Clean Bandit Blue Jeans Lana Del Rey Rolling in the deep Adel Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Scream & Shout Will.i.am Don't Stop the Party Pitbull TJR Shake It Off Taylor swift Don't You Worry Child Swedish House Mafia Stay With Me Sam Smith Duke Demont Need U (100%) Stolen Dance Milky Chance Fancy Iggy Azalea Summer Calvin Harris Feel So Close Calvin Harris Summertime Sadness Lana Del Rey Feel The Love Rudimental Sweet Nothing Calvin Harris Forget You Cee Lo Green Thinking About You Calvin Harris Get Lucky Daft Punk Titanium David Guetta Good Feeling Flo Rida Treasure Bruno Mars Happy Pharrell Williams Uptown Funk Mark Ronson I love it Icona Pop Valerie Amy Winehouse I Need Your Love Calvin Harris Wake Me Up Avicii I'm Not The Only One Sam Smith Waves Mr Probz In My Mind Ivan Gough We Found Love / I Wanna Dance Whitney Houston ft With Somebody Rihanna Locked Out Of Heaven Bruno Mars White Noise Disclosure Lost Frank Ocean Love Me Again John Newman Classics Song List 2015 SONG NAME ARTIST LIKE? SONG NAME ARTIST LIKE? 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters Could You Be Loved Bob Marley 4 Minutes Madonna Feat Justin Crazy Gnarls Barkley Timberlake Crazy In Love Beyoncé Addicted To You Avicii Dancando La Fiesta Sound System Ain't No Mountain High Enough Marvin Gaye Dare Gorillaz Ain't No Other Man Christina Aguilera Day N Nite Kid Cudi Ain't No