Conceptual Model of High Country Burning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 13: Broken River Catchment

13 Broken River Catchment Argus, 15 January 1924 True Tales of the Trout Cod: River Histories of the Murray-Darling Basin 13-1 NORTHERN BLACKFISH Noting J. T. Anderson’s remarks on the subject, “R.G.K.” (Richmond) says that he has just had a “fortnight’s fishing in the Broken River and various creeks around Lima (via Benalla) Although he had good sport with Murray cod, bream (Macquarie perch), and catfish, which he remarks is a far finer table fish than is generally realised, he noticed, too, how numerous were the blackfish. He must have hooked over a hundred, but returned them all to the river, as according to the Game Laws, they may not be kept under 8 inches, and very few of these were eight inches, many as small as four inches. Had “R.G.K.” known, he might have kept these fish, because an exception is made about them. The regulation reads:- “Blackfish, except those in streams flowing north from the Great Dividing Range, 8 1/2 inches.” These blackfish are a smaller species or variety, and the Fisheries department imposes no conditions in regard to them. Argus, 15 January 1924 13-2 True Tales of the Trout Cod: River Histories of the Murray-Darling Basin Figure 13.1 The Broken River Catchment showing major waterways and key localities. True Tales of the Trout Cod: River Histories of the Murray-Darling Basin 13-3 13.1 Early European Accounts The Broken River rises at the foot of Mt Buller north of Mansfield and, travelling west, collects water from tributaries originating in the Strathbogie and Wombat Ranges. -

Gauging Station Index

Site Details Flow/Volume Height/Elevation NSW River Basins: Gauging Station Details Other No. of Area Data Data Site ID Sitename Cat Commence Ceased Status Owner Lat Long Datum Start Date End Date Start Date End Date Data Gaugings (km2) (Years) (Years) 1102001 Homestead Creek at Fowlers Gap C 7/08/1972 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 19.9 -31.0848 141.6974 GDA94 07/08/1972 16/12/1995 23.4 01/01/1972 01/01/1996 24 Rn 1102002 Frieslich Creek at Frieslich Dam C 21/10/1976 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 8 -31.0660 141.6690 GDA94 19/03/1977 31/05/2003 26.2 01/01/1977 01/01/2004 27 Rn 1102003 Fowlers Creek at Fowlers Gap C 13/05/1980 31/05/2003 Closed DWR 384 -31.0856 141.7131 GDA94 28/02/1992 07/12/1992 0.8 01/05/1980 01/01/1993 12.7 Basin 201: Tweed River Basin 201001 Oxley River at Eungella A 21/05/1947 Open DWR 213 -28.3537 153.2931 GDA94 03/03/1957 08/11/2010 53.7 30/12/1899 08/11/2010 110.9 Rn 388 201002 Rous River at Boat Harbour No.1 C 27/05/1947 31/07/1957 Closed DWR 124 -28.3151 153.3511 GDA94 01/05/1947 01/04/1957 9.9 48 201003 Tweed River at Braeside C 20/08/1951 31/12/1968 Closed DWR 298 -28.3960 153.3369 GDA94 01/08/1951 01/01/1969 17.4 126 201004 Tweed River at Kunghur C 14/05/1954 2/06/1982 Closed DWR 49 -28.4702 153.2547 GDA94 01/08/1954 01/07/1982 27.9 196 201005 Rous River at Boat Harbour No.3 A 3/04/1957 Open DWR 111 -28.3096 153.3360 GDA94 03/04/1957 08/11/2010 53.6 01/01/1957 01/01/2010 53 261 201006 Oxley River at Tyalgum C 5/05/1969 12/08/1982 Closed DWR 153 -28.3526 153.2245 GDA94 01/06/1969 01/09/1982 13.3 108 201007 Hopping Dick Creek -

Taking Control Spring 2020 Newsletter

Spring 2020 Taking Control Support, information and resources for individuals and communities impacted by wild dogs Above: Wild dog exclusion fencing contructed with Bushfire Recovery Funding. Inset: Combined Bushfire Recovery Fund and DeFence fencing across eastern Victoria. Source: DELWP. Bushfire recovery aids wild dog control Significantly, more than half of the BRF fencing The Community Wild Dog Control comprises Wild Dog Exclusion Fencing (WDEF), bringing Coordinators and members of the the total amount of publicly-funded WDEF erected in both regions in 2019-20 to 516km. (Seventy-five km of Wild Dog Program have been WDEF was constructed under the DeFence Project, helping farmers replace fences which was funded by the Commonwealth Government’s lost in the 2019-20 bushfires, Communities Combating Pests and Weed Impacts strengthening wild dog control in During Drought Program (see page 4).) These stretches of WDEF (see image above) are helping the process. farmers protect livestock from the threat of wild dog predation which can increase after bushfire. The Community Wild Dog Coordinators (CWDCCs) and members of the Wild Dog Program (WDP) have helped Further assistance is being offered by the WDP which farmers access funding under the Victorian has secured funding under Work for Victoria to hire an Government’s Bushfire Recovery Fencing (BRF) program. additional four Wild Dog Controllers (WDCs) for the next few months. Almost every application has been processed, resulting in the construction of 584km of new fencing in Gippsland and 277km in the Hume. delwp.vic.gov.au Spring 2020 Above: CWDCCs, Lucy-Anne Cobby, Brian Dowley and Mick Freeman. -

The Canberra • B Ush Walking Club ( Inc. Newsletter

THE CANBERRA • B USH WALKING CLUB ( INC. NEWSLETTER GPO Box 160, Canberra ACT 2601 VOLUME 36 October 2000 NUMBER 10 OCTOBER GENERAL MEETING 8pm Wednesday 18th Speaker: Betty Kitchener, on 'Field First Aid' Woden Library Community Room Make the most of the evening and join other members at 6. OOpm for a convivial meal at the Chinese Kitchen 6)10 Restaurant in Corinna Street, Shop 091, Woden Plaza, Phi/lip. to be early to ensure there will be ample time to finish and still get to the meeting in good ti PRESIDENT'S • Membership fees have been increased to $25 (single) and Also In This Issue: PRATTLE $33 (household) Item Page • The Club transport rate has PRESIDENT'S PRATTLE For those of you who were unable been increased to to make last month's Annual Gen- MEMBERSHIP MATTERS 2 30cents/kilometrelvehicle. eral Meeting, the key outcomes are MOTIONS PASSED AT AGM 2 as follows: Contact details for the Committee " are shown on the back page of each 39 ANNUAL REPORT 2 We have four brand new Com- It. Please don't hesitate to give us a CBC 40th ANNIVERSARY 4 mittee members - Ailsa Brown call if you have concerns about the TRIP PREVIEWS 4 (Publisher), Michael Macona- way we are doing things or have chie (Conservation Officer), some suggestions for how we might WALKS WAFFLE 5 Michael Sutton (Treasurer), do things better. A bit of praise LETTERS TO THE EDITOR. 6 and Rosanne Walker (Social from time to time helps keep us TRIP REPORTS 7 Secretary), replacing Vance going so do let us know if we do Brown, Janet Edstein, Cate something that pleases you. -

Flora & Fauna Survey of Nalbaugh State Forest (Part) Bombala District, Eden Region, South-Eastern

This document has been scanned from hard-copy archives for research and study purposes. Please note not all information may be current. We have tried, in preparing this copy, to make the content accessible to the widest possible audience but in some cases we recognise that the automatic text recognition maybe inadequate and we apologise in advance for any inconvenience this may cause. FOREST RESOURCES SERIES NO. 9 FLORA AND FAUNA SURVEY OF NAL~AUGH STATE FOREST (PART) BOMBALA DISTRICT, EDEN REGION, SOUTH-EASTERN NEW SOUTH WALES BY D.L. BINNS AND- R.P. KAVANAGH FORESTRY COMMISSION OF NEW SOUTH WALES FLORA AND FAUNA SURVEY OF NALBAUGH STATE FOREST (PART), BOMBALA DISTRICT, EDEN REGION, SOUTH-EASTERN NEW SOUTH WALES by DoL.Binns and RoPo Kavanagh FOREST ECOLOGY SECTION WOOD TECHNOLOGY AND FOREST RESEARCH DIVISION FORESTRY COMMISSION OF NEW SOUTH WALES SYDNEY 1990 Forest Resources Series No. 9 1989 Published by: Forestry Commission ofNew South Wales, Wood Technology and Forest Research Division, 27 Oratava Avenue, West Pennant Hills. N.S.W. 2120 r.o, Box 100, Beecroft. N.S.W. 2119 Australia. Copyright@ 1989 by Forestry Commission ofNew South Wales ODC 182.5:156.2 (944) ISSN 1033-1220 , ISBN 073055676 X /' ./ r Flora and Fauna Survey of Nalbaugh State Forest (Part), Bombala Dlstrlct, Eden Region: -I- CONTENTS PAGE .ABSTRACT ...........................,............. 1 INTRODUCTION 2 THE STUDY AREA 2 1. Location ......................................... .2 2. Physiography and Geology .............................'. .2 3. Disturbance History .................................. .3 A. FLORA 5 METHODS 5 1. Site Location ....'................................... 5 2. Floristics and Vegetation Structural Data ...................... 5 3. Previous Floristic Studies 6 4. -

Regional Patterns of Erosion and Sediment and Nutrient Transport in the Goulburn and Broken River Catchments, Victoria

Regional Patterns of Erosion and Sediment and Nutrient Transport in the Goulburn and Broken River Catchments, Victoria R.C. DeRose, I.P.Prosser, L.J. Wilkinson, A.O. Hughes and W.J. Young CSIRO Land and Water, Canberra Technical Report 11/03, March 2003 CSIRO LAND and WATER Regional Patterns of Erosion and Sediment and Nutrient Transport in the Goulburn and Broken River Catchments, Victoria R.C. DeRose, I.P. Prosser, L.J. Wilkinson, A.O. Hughes and W.J. Young CSIRO Land and Water, Canberra Technical Report 11/03, March 2003 Copyright ©2003 CSIRO Land and Water To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO Land and Water. Important Disclaimer To the extent permitted by law, CSIRO Land and Water (including its employees and consultants) excludes all liability to any person for any consequences, including but not limited to all losses, damages, costs, expenses and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and any information or material contained in it. ISSN 1446-6163 Table of Contents Acknowledgments..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract........................................................................................................................................................................ -

Taylors Hill-Werribee South Sunbury-Gisborne Hurstbridge-Lilydale Wandin East-Cockatoo Pakenham-Mornington South West

TAYLORS HILL-WERRIBEE SOUTH SUNBURY-GISBORNE HURSTBRIDGE-LILYDALE WANDIN EAST-COCKATOO PAKENHAM-MORNINGTON SOUTH WEST Metro/Country Postcode Suburb Metro 3200 Frankston North Metro 3201 Carrum Downs Metro 3202 Heatherton Metro 3204 Bentleigh, McKinnon, Ormond Metro 3205 South Melbourne Metro 3206 Albert Park, Middle Park Metro 3207 Port Melbourne Country 3211 LiQle River Country 3212 Avalon, Lara, Point Wilson Country 3214 Corio, Norlane, North Shore Country 3215 Bell Park, Bell Post Hill, Drumcondra, Hamlyn Heights, North Geelong, Rippleside Country 3216 Belmont, Freshwater Creek, Grovedale, Highton, Marhsall, Mt Dunede, Wandana Heights, Waurn Ponds Country 3217 Deakin University - Geelong Country 3218 Geelong West, Herne Hill, Manifold Heights Country 3219 Breakwater, East Geelong, Newcomb, St Albans Park, Thomson, Whington Country 3220 Geelong, Newtown, South Geelong Anakie, Barrabool, Batesford, Bellarine, Ceres, Fyansford, Geelong MC, Gnarwarry, Grey River, KenneQ River, Lovely Banks, Moolap, Moorabool, Murgheboluc, Seperaon Creek, Country 3221 Staughtonvale, Stone Haven, Sugarloaf, Wallington, Wongarra, Wye River Country 3222 Clilon Springs, Curlewis, Drysdale, Mannerim, Marcus Hill Country 3223 Indented Head, Port Arlington, St Leonards Country 3224 Leopold Country 3225 Point Lonsdale, Queenscliffe, Swan Bay, Swan Island Country 3226 Ocean Grove Country 3227 Barwon Heads, Breamlea, Connewarre Country 3228 Bellbrae, Bells Beach, jan Juc, Torquay Country 3230 Anglesea Country 3231 Airleys Inlet, Big Hill, Eastern View, Fairhaven, Moggs -

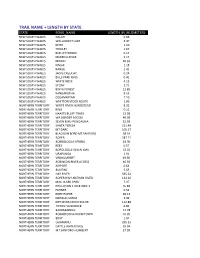

Trail Name + Length by State

TRAIL NAME + LENGTH BY STATE STATE ROAD_NAME LENGTH_IN_KILOMETERS NEW SOUTH WALES GALAH 0.66 NEW SOUTH WALES WALLAGOOT LAKE 3.47 NEW SOUTH WALES KEITH 1.20 NEW SOUTH WALES TROLLEY 1.67 NEW SOUTH WALES RED LETTERBOX 0.17 NEW SOUTH WALES MERRICA RIVER 2.15 NEW SOUTH WALES MIDDLE 40.63 NEW SOUTH WALES NAGHI 1.18 NEW SOUTH WALES RANGE 2.42 NEW SOUTH WALES JACKS CREEK AC 0.24 NEW SOUTH WALES BILLS PARK RING 0.41 NEW SOUTH WALES WHITE ROCK 4.13 NEW SOUTH WALES STONY 2.71 NEW SOUTH WALES BINYA FOREST 12.85 NEW SOUTH WALES KANGARUTHA 8.55 NEW SOUTH WALES OOLAMBEYAN 7.10 NEW SOUTH WALES WHITTON STOCK ROUTE 1.86 NORTHERN TERRITORY WAITE RIVER HOMESTEAD 8.32 NORTHERN TERRITORY KING 0.53 NORTHERN TERRITORY HAASTS BLUFF TRACK 13.98 NORTHERN TERRITORY WA BORDER ACCESS 40.39 NORTHERN TERRITORY SEVEN EMU‐PUNGALINA 52.59 NORTHERN TERRITORY SANTA TERESA 251.49 NORTHERN TERRITORY MT DARE 105.37 NORTHERN TERRITORY BLACKGIN BORE‐MT SANFORD 38.54 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROPER 287.71 NORTHERN TERRITORY BORROLOOLA‐SPRING 63.90 NORTHERN TERRITORY REES 0.57 NORTHERN TERRITORY BOROLOOLA‐SEVEN EMU 32.02 NORTHERN TERRITORY URAPUNGA 1.91 NORTHERN TERRITORY VRDHUMBERT 49.95 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROBINSON RIVER ACCESS 46.92 NORTHERN TERRITORY AIRPORT 0.64 NORTHERN TERRITORY BUNTINE 5.63 NORTHERN TERRITORY HAY RIVER 335.62 NORTHERN TERRITORY ROPER HWY‐NATHAN RIVER 134.20 NORTHERN TERRITORY MAC CLARK PARK 7.97 NORTHERN TERRITORY PHILLIPSON STOCK ROUTE 55.84 NORTHERN TERRITORY FURNER 0.54 NORTHERN TERRITORY PORT ROPER 40.13 NORTHERN TERRITORY NDHALA GORGE 3.49 NORTHERN TERRITORY -

Rivers and Streams Special Investigation Final Recommendations

LAND CONSERVATION COUNCIL RIVERS AND STREAMS SPECIAL INVESTIGATION FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS June 1991 This text is a facsimile of the former Land Conservation Council’s Rivers and Streams Special Investigation Final Recommendations. It has been edited to incorporate Government decisions on the recommendations made by Order in Council dated 7 July 1992, and subsequent formal amendments. Added text is shown underlined; deleted text is shown struck through. Annotations [in brackets] explain the origins of the changes. MEMBERS OF THE LAND CONSERVATION COUNCIL D.H.F. Scott, B.A. (Chairman) R.W. Campbell, B.Vet.Sc., M.B.A.; Director - Natural Resource Systems, Department of Conservation and Environment (Deputy Chairman) D.M. Calder, M.Sc., Ph.D., M.I.Biol. W.A. Chamley, B.Sc., D.Phil.; Director - Fisheries Management, Department of Conservation and Environment S.M. Ferguson, M.B.E. M.D.A. Gregson, E.D., M.A.F., Aus.I.M.M.; General Manager - Minerals, Department of Manufacturing and Industry Development A.E.K. Hingston, B.Behav.Sc., M.Env.Stud., Cert.Hort. P. Jerome, B.A., Dip.T.R.P., M.A.; Director - Regional Planning, Department of Planning and Housing M.N. Kinsella, B.Ag.Sc., M.Sci., F.A.I.A.S.; Manager - Quarantine and Inspection Services, Department of Agriculture K.J. Langford, B.Eng.(Ag)., Ph.D , General Manager - Rural Water Commission R.D. Malcolmson, M.B.E., B.Sc., F.A.I.M., M.I.P.M.A., M.Inst.P., M.A.I.P. D.S. Saunders, B.Agr.Sc., M.A.I.A.S.; Director - National Parks and Public Land, Department of Conservation and Environment K.J. -

Genoa River Correa Correa Lawrenciana Var

Action S tatement Flora and F auna Guarantee Act 1988 No. 21 7 Genoa River Correa Correa lawrenciana var. genoensis This Action Statement is based on a draft Recovery Plan prepared for this species by DSE under contract to the Australian Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. Description Genoa River Correa (Correa lawrenciana var. genoensis ) is an erect to spreading shrub which grows to 2 m in height (Walsh & Entwisle 1999). It has ovate leaves to 7 x 4 cm. The upper leaf surface is dark green, glossy and hairless; the lower surface is pale grey-green and densely covered with stellate hairs (Walsh & Entwisle 1999). The leaf margins are smooth. The flowers tend to be solitary, are drooping, yellow-green and tubular, with four curved, triangular lobes at the end of tube. They are hairy outside, and grow to 25 mm long (Walsh & Entwisle 1999; DNRE 2001). The calyx is hemispherical, more or less hairless, up to 5 mm long, and has four conspicuous teeth. The Genoa River Correa stamens protrude from the flower. Flowering (Photo:DSE/McCann ) largely occurs in spring (Walsh & Entwisle 1999). Genoa River Correa differs from the type variety in its prominently gland-dotted calyx with long acuminate lobes (Wilson 1961). The key to Mountain Correa ( Correa lawrenciana ) varieties in Walsh & Entwisle (1999) further distinguishes the Genoa Correa ( C. lawrenciana var. genoensis ) as having a green and glabrescent calyx. Distribution Genoa River Correa is restricted to a few very small populations in far-east Victoria fringing the Genoa River, and one population in south-eastern New South Wales, fringing Redstone Creek. -

The Geology and Prospectivity of the Tallangatta 1:250 000 Sheet

VIMP Report 10 The geology and prospectivity of the Tallangatta 1:250 000 sheet I.D. Oppy, R.A. Cayley & J. Caluzzi November 1995 Bibliographic reference: OPPY, I.D., CAYLEY R.A. & CALUZZI, J., 1995. The Geology and prospectivity of the Tallangatta 1:250 000 sheet Victorian Initiative for Minerals and Petroleum Report 10. Department of Agriculture, Energy and Minerals. © Crown (State of Victoria) Copyright 1995 Geological Survey of Victoria ISSN 1323 4536 ISBN 0 7306 7980 2 This report may be purchased from: Business Centre, Department of Agriculture, Energy & Minerals, Ground Floor, 115 Victoria Parade, Fitzroy, Victoria 3065 For further technical information contact: General Manager, Geological Survey of Victoria, Department of Agriculture, Energy & Minerals, P O Box 2145, MDC Fitzroy, Victoria 3065 Acknowledgments: The authors wish to acknowledge G. Ellis for formatting the document, R. Buckley, P.J. O'Shea and D.H. Taylor for editing and S. Heeps for cartography I. Oppy wrote chapters 3 and 5, R. Cayley wrote chapter 2 and J. Caluzzi wrote chapter 4. GEOLOGY AND PROSPECTIVITY - TALLANGATTA 1 Contents Abstract 4 1 Introduction 5 2 Geology 7 2.1 Geological history 7 Pre-Ordovician to Early Silurian 7 Early Silurian Benambran deformation and widespread granite intrusion 8 Middle to Late Silurian 9 Late Silurian Bindian deformation 9 Early Devonian rifting and volcanism 10 Middle Devonian Tabberabberan deformation 11 Late Devonian sedimentation and volcanism 11 Early Carboniferous Kanimblan deformation to Present day 11 2.2 Stratigraphy -

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 112 Monday, 3 September 2007 Published Under Authority by Government Advertising

6835 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 112 Monday, 3 September 2007 Published under authority by Government Advertising SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT EXOTIC DISEASES OF ANIMALS ACT 1991 ORDER - Section 15 Declaration of Restricted Areas – Hunter Valley and Tamworth I, IAN JAMES ROTH, Deputy Chief Veterinary Offi cer, with the powers the Minister has delegated to me under section 67 of the Exotic Diseases of Animals Act 1991 (“the Act”) and pursuant to section 15 of the Act: 1. revoke each of the orders declared under section 15 of the Act that are listed in Schedule 1 below (“the Orders”); 2. declare the area specifi ed in Schedule 2 to be a restricted area; and 3. declare that the classes of animals, animal products, fodder, fi ttings or vehicles to which this order applies are those described in Schedule 3. SCHEDULE 1 Title of Order Date of Order Declaration of Restricted Area – Moonbi 27 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Woonooka Road Moonbi 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Anambah 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Muswellbrook 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Aberdeen 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – East Maitland 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Timbumburi 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – McCullys Gap 30 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Bunnan 31 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area - Gloucester 31 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Eagleton 29 August 2007 SCHEDULE 2 The area shown in the map below and within the local government areas administered by the following councils: Cessnock City Council Dungog Shire Council Gloucester Shire Council Great Lakes Council Liverpool Plains Shire Council 6836 SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT 3 September 2007 Maitland City Council Muswellbrook Shire Council Newcastle City Council Port Stephens Council Singleton Shire Council Tamworth City Council Upper Hunter Shire Council NEW SOUTH WALES GOVERNMENT GAZETTE No.