A Comparison of an Automated Freezing Drizzle Algorithm to Human Observations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Winter Forecasting Handbook Winter Storm Information That Is Useful to the Public

A Winter Forecasting Handbook Winter storm information that is useful to the public: 1) The time of onset of dangerous winter weather conditions 2) The time that dangerous winter weather conditions will abate 3) The type of winter weather to be expected: a) Snow b) Sleet c) Freezing rain d) Transitions between these three 7) The intensity of the precipitation 8) The total amount of precipitation that will accumulate 9) The temperatures during the storm (particularly if they are dangerously low) 7) The winds and wind chill temperature (particularly if winds cause blizzard conditions where visibility is reduced). 8) The uncertainty in the forecast. Some problems facing meteorologists: Winter precipitation occurs on the mesoscale The type and intensity of winter precipitation varies over short distances. Forecast products are not well tailored to winter Subtle features, such as variations in the wet bulb temperature, orography, urban heat islands, warm layers aloft, dry layers, small variations in cyclone track, surface temperature, and others all can influence the severity and character of a winter storm event. FORECASTING WINTER WEATHER Important factors: 1. Forcing a) Frontal forcing (at surface and aloft) b) Jetstream forcing c) Location where forcing will occur 2. Quantitative precipitation forecasts from models 3. Thermal structure where forcing and precipitation are expected 4. Moisture distribution in region where forcing and precipitation are expected. 5. Consideration of microphysical processes Forecasting winter precipitation in 0-48 hour time range: You must have a good understanding of the current state of the Atmosphere BEFORE you try to forecast a future state! 1. Examine current data to identify positions of cyclones and anticyclones and the location and types of fronts. -

High-Resolution Simulations of Freezing Drizzle and Freezing Rain and Comparisons to Observations

High-resolution simulations of freezing drizzle and freezing rain and comparisons to observations Greg Thompson Research Applications Laboratory National Center for Atmospheric Research additional contributions by: Roy Rasmussen, Trude Eidhammer, Kyoko Ikeda, Changhai Liu, Pedro Jimenez, Mei Xu, Stan Benjamin Winterwind 7 Feb 2017, Skelleftea, Sweden Outline • Brief History • High-Resolution Forecasts o Supercooled water drops aloft o Ground icing • Verification o Weather Research & Forecasting, WRF o High Resolution Rapid Refresh, HRRR • Next steps o Time-lag ensemble average o Making clouds better o WISLINE project and AROME model With respect to Numerical Weather Prediction The microphysics scheme is a component in a weather model responsible for: • Condensing water vapor into droplets • Model collisions with other droplets to become drizzle/rain • Creating ice crystals via droplet freezing or vapor-to-ice conversion • Growing ice crystals to snow size • Letting snow collect cloud water droplets (riming or accretion) • Large drops freeze into hail, snow rimes heavily to create graupel • Making rain, snow, and graupel fall to earth • etc. The treatment of processes going between water vapor, liquid water, and ice. Cloud physics & precipitation NCAR-RAL microphysics scheme Scheme version/generation Research or operational model Reisner, Rasmussen, Bruintjes (1998MWR) MM5 Rapid Update Cycle (RUC) Thompson, Rasmussen, Manning (2004MWR) MM5 WRF RUC Thompson, Field, Rasmussen, Hall (2008MWR) MM5 WRF & HWRF RUC Rapid Refresh (RAP) High-Res -

FAA Advisory Circular AC 91-74B

U.S. Department Advisory of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration Circular Subject: Pilot Guide: Flight in Icing Conditions Date:10/8/15 AC No: 91-74B Initiated by: AFS-800 Change: This advisory circular (AC) contains updated and additional information for the pilots of airplanes under Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) parts 91, 121, 125, and 135. The purpose of this AC is to provide pilots with a convenient reference guide on the principal factors related to flight in icing conditions and the location of additional information in related publications. As a result of these updates and consolidating of information, AC 91-74A, Pilot Guide: Flight in Icing Conditions, dated December 31, 2007, and AC 91-51A, Effect of Icing on Aircraft Control and Airplane Deice and Anti-Ice Systems, dated July 19, 1996, are cancelled. This AC does not authorize deviations from established company procedures or regulatory requirements. John Barbagallo Deputy Director, Flight Standards Service 10/8/15 AC 91-74B CONTENTS Paragraph Page CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1. Purpose ..............................................................................................................................1 1-2. Cancellation ......................................................................................................................1 1-3. Definitions.........................................................................................................................1 1-4. Discussion .........................................................................................................................6 -

Exploring the MBL Cloud and Drizzle Microphysics Retrievals from Satellite, Surface and Aircraft

Exploring the MBL cloud and drizzle microphysics retrievals from satellite, surface and aircraft Xiquan Dong, University of Arizona Pat Minnis, SSAI 1. Briefly describe our 2. Can we utilize these surface newly developed retrieval retrievals to develop cloud (and/or drizzle) Re profile for algorithm using ARM radar- CERES team? lidar, and comparison with aircraft data. Re is a critical for radiation Wu et al. (2020), JGR and aerosol-cloud- precipitation interactions, as well as warm rain process. 1 A long-term Issue: CERES Re is too large, especially under drizzling MBL clouds A/C obs in N Atlantic • Cloud droplet size retrievals generally too high low clouds • Especially large for Re(1.6, 2.1 µm) CERES Re too large Worse for larger Re • Cloud heterogeneity plays a role, but drizzle may also be a factor - Can we understand the impact of drizzle on these NIR retrievals and their differences with Painemal et al. 2020 ground truth? A/C obs in thin Pacific Sc with drizzle CERES LWP high, tau low, due to large Re Which will lead to high SW transmission at the In thin drizzlers, Re is overestimated by 3 µm surface and less albedo at TOA Wood et al. JAS 2018 Painemal et al. JGR 2017 2 Profiles of MBL Cloud and Drizzle Microphysical Properties retrieved from Ground-based Observations and Validated by Aircraft data during ACE-ENA IOP 푫풎풂풙 ퟔ Radar reflectivity: 풁 = ퟎ 푫 푵풅푫 Challenge is to simultaneously retrieve both cloud and drizzle properties within an MBL cloud layer using radar-lidar observations because radar reflectivity depends on the sixth power of the particle size and can be highly weighted by a few large drizzle drops in a drizzling cloud 3 Wu et al. -

7.2 DEVELOPMENT of a METEOROLOGICAL PARTICLE SENSOR for the OBSERVATION of DRIZZLE Richard Lewis* National Weather Service St

7.2 DEVELOPMENT OF A METEOROLOGICAL PARTICLE SENSOR FOR THE OBSERVATION OF DRIZZLE Richard Lewis* National Weather Service Sterling, VA 20166 Stacy G. White Science Applications International Corporation Sterling, VA 20166 1. INTRODUCTION “Very small, numerous, and uniformly dispersed, water drops that may appear to float while The National Weather Service (NWS) and Federal following air currents. Unlike fog droplets, drizzle Aviation Administration (FAA) are jointly participating in a falls to the ground. It usually falls from low Product Improvement Program to improve the capabilities stratus clouds and is frequently accompanied by of the of Automated Surface Observing Systems (ASOS). low visibility and fog. The greatest challenge in the ASOS was to automate the visual elements of the observation; sky conditions, visibility In weather observations, drizzle is classified as and type of weather. Despite achieving some success in (a) “very light”, comprised of scattered drops that this area, limitations in the reporting capabilities of the do not completely wet an exposed surface, ASOS remain. As currently configured, the ASOS uses a regardless of duration; (b) “light,” the rate of fall Precipitation Identifier that can only identify two being from a trace to 0.25 mm per hour: (c) precipitation types, rain and snow. A goal of the Product “moderate,” the rate of fall being 0.25-0.50 mm Improvement program is to replace the current PI sensor per hour:(d) “heavy” the rate of fall being more with one that can identify additional precipitation types of than 0.5 mm per hour. When the precipitation importance to aviation. Highest priority is being given to equals or exceeds 1mm per hour, all or part of implementing capabilities of identifying ice pellets and the precipitation is usually rain; however, true drizzle. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

Literature Review and Scientific Synthesis on the Efficacy of Winter Orographic Cloud Seeding

Statement on the Application of Winter Orographic Cloud Seeding For Water Supply and Energy Production Literature Review and Scientific Synthesis on the Efficacy of Winter Orographic Cloud Seeding A Report to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation January 2015 Prepared by David W. Reynolds CIRES Boulder, Co 1 Technical Memorandum This information is distributed solely for the purpose of pre-dissemination peer review under applicable information quality guidelines. It has not been formally disseminated by the Bureau of Reclamation. It does not represent and should not be construed to represent Reclamation’s determination or policy. As such, the findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Reclamation. 2 Statement on the Application of Winter Orographic Cloud Seeding For Water Supply and Energy Production 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 5 1.1. Introduction to Winter Orographic Cloud Seeding .......................................................... 5 1.2 Purpose of this Study........................................................................................................ 5 1.3 Relevance and Need for a Reassessment of the Role of Winter Orographic Cloud Seeding to Enhance Water Supplies in the West ........................................................................ 6 1.4 NRC 2003 Report on Critical Issues in Weather Modification – Critical Issues Concerning Winter Orographic -

Evaluation of Satellite Rainfall Estimates for Drought and Flood Monitoring in Mozambique

Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 1758-1776; doi:10.3390/rs70201758 OPEN ACCESS remote sensing ISSN 2072-4292 www.mdpi.com/journal/remotesensing Article Evaluation of Satellite Rainfall Estimates for Drought and Flood Monitoring in Mozambique Carolien Toté 1,*, Domingos Patricio 2, Hendrik Boogaard 3, Raymond van der Wijngaart 3, Elena Tarnavsky 4 and Chris Funk 5 1 Flemish Institute for Technological Research (VITO), Remote Sensing Unit, Boeretang 200, 2400 Mol, Belgium 2 Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia (INAM), Rua de Mukumbura 164, C.P. 256, Maputo, Mozambique; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Alterra, Wageningen University, PO Box 47, 3708PB Wageningen, The Netherlands; E-Mails: [email protected] (H.B.); [email protected] (R.W.) 4 Department of Meteorology, University of Reading, Earley Gate, PO Box 243, Reading RG6 6BB, UK; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 United States Geological Survey/Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center and the Climate Hazard Group, Geography Department, University of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-14-336844; Fax: +32-14-322795. Academic Editor: George P. Petropoulos and Prasad S. Thenkabail Received: 8 August 2014 / Accepted: 29 January 2015 / Published: 5 February 2015 Abstract: Satellite derived rainfall products are useful for drought and flood early warning and overcome the problem of sparse, unevenly distributed and erratic rain gauge observations, provided their accuracy is well known. Mozambique is highly vulnerable to extreme weather events such as major droughts and floods and thus, an understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of different rainfall products is valuable. -

Print Key. (Pdf)

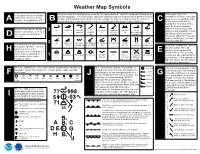

Weather Map Symbols Along the center, the cloud types are indicated. The top symbol is the high-level cloud type followed by the At the upper right is the In the upper left, the temperature mid-level cloud type. The lowest symbol represents low-level cloud over a number which tells the height of atmospheric pressure reduced to is plotted in Fahrenheit. In this the base of that cloud (in hundreds of feet) In this example, the high level cloud is Cirrus, the mid-level mean sea level in millibars (mb) A example, the temperature is 77°F. B C C to the nearest tenth with the cloud is Altocumulus and the low-level clouds is a cumulonimbus with a base height of 2000 feet. leading 9 or 10 omitted. In this case the pressure would be 999.8 mb. If the pressure was On the second row, the far-left Ci Dense Ci Ci 3 Dense Ci Cs below Cs above Overcast Cs not Cc plotted as 024 it would be 1002.4 number is the visibility in miles. In from Cb invading 45° 45°; not Cs ovcercast; not this example, the visibility is sky overcast increasing mb. When trying to determine D whether to add a 9 or 10 use the five miles. number that will give you a value closest to 1000 mb. 2 As Dense As Ac; semi- Ac Standing Ac invading Ac from Cu Ac with Ac Ac of The number at the lower left is the a/o Ns transparent Lenticularis sky As / Ns congestus chaotic sky Next to the visibility is the present dew point temperature. -

Development and Demonstration of a Freezing Drizzle Algorithm for Roadway Environmental Sensing Systems

Development and Demonstration of a Freezing Drizzle Algorithm for Roadway Environmental Sensing Systems http://aurora-program.org Aurora Project 2007-04 Final Report October 2012 About Aurora Aurora is an international program of collaborative research, development and deployment in the field of road and weather information systems (RWIS), serving the interests and needs of public agencies. The Aurora vision is to deploy RWIS to integrate state-of-the-art road and weather forecasting technologies with coordinated, multi-agency weather monitoring infrastructures. It is hoped this will facilitate advanced road condition and weather monitoring and forecasting capabilities for efficient highway maintenance, and the provision of real-time information to travelers. Disclaimer Notice The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the information presented herein. The opinions, findings and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the sponsors. The sponsors assume no liability for the contents or use of the information contained in this document. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. The sponsors do not endorse products or manufacturers. Trademarks or manufacturers’ names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the objective of the document. Non-Discrimination Statement Iowa State University does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, age, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, gender identity, genetic information, sex, marital status, disability, or status as a U.S. veteran. Inquiries can be directed to the Director of Equal Opportunity and Compliance, 3280 Beardshear Hall, (515) 294-7612. -

Ice Storm Learning Module

Ice Storm Learning Module In the United States there are over 1.4 million car accidents each year that occur due to freezing precipitation. From these accidents, there are over 600,000 injuries and 7,000 deaths. Freezing precipitation is responsible for about 20% of all weather- related fatalities, and thus it is abundantly clear why we must learn how freezing rain forms in winter low pressure systems 1. Our goal in this learning module is to first uncover the meteorology of ice storms and then discuss winter storm safety. Figure 1. Images from an ice storm in Arkansas in 2009. Source Introduction The National Weather Service will issue a freezing rain warning on the forecast of at least ¼ inch accumulation of ice. Aside from making automobile travel treacherous, ice is extremely heavy when it accumulates on trees and power lines. In fact, a ½” coating of ice on a single, standard length (300 ft) power line in a residential area can add nearly 300 lbs of weight. Put an inch of ice on the same power line and you will add 800 lbs! It is easy to see why the power lines are down in the images in Figure 1. As an interesting side note, at the University of Illinois all power lines are buried beneath the ground to protect the university’s power infrastructure in the event of a major ice storm. Before we dig into the meteorology behind an ice storm, let’s take a few minutes to learn some important facts about ice. 1. Liquid water is more dense than ice. -

Name That Cloud!

Period _____ Name ___________________________ Name That Cloud! What’s the weather going to be like today? We’re always asking that. We need to know. The weather affects what we wear, what we need to take with us, and what we do. Will we need to wear shorts, or a sweater and warm pants? Will we need to take an umbrella or a heavy coat? Can we play outside after school? You can learn to predict the weather. You don’t need a lot of equipment or fancy stuff – just use your eyes! Go outside and look at the clouds. Clouds come in different shapes, sizes, and colors. You can use what you know about clouds to find out what the weather will bring. Okay, here’s what you need to know about clouds. Clouds are named by the way they look. We use Latin root words to name them. Clouds come in different sizes and shapes. They are formed and drift along at different heights in the sky. All of these things help us name them and know what kind of weather they may bring. There are three main types of clouds: cumulus, cirrus, and stratus. When the weather is fair, we see cumulus clouds. Fair weather is fine, sunny weather with no chance of rain, snow, or any other precipitation. Cumulus clouds are white, puffy clouds that may look like cauliflower. In Latin, cumulus means “heap.” You may see heaps and heaps of these white, fluffy, cotton-ball-looking clouds. Usually there are large spaces of clear blue sky in between them.