Literature Review and Scientific Synthesis on the Efficacy of Winter Orographic Cloud Seeding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soaring Weather

Chapter 16 SOARING WEATHER While horse racing may be the "Sport of Kings," of the craft depends on the weather and the skill soaring may be considered the "King of Sports." of the pilot. Forward thrust comes from gliding Soaring bears the relationship to flying that sailing downward relative to the air the same as thrust bears to power boating. Soaring has made notable is developed in a power-off glide by a conven contributions to meteorology. For example, soar tional aircraft. Therefore, to gain or maintain ing pilots have probed thunderstorms and moun altitude, the soaring pilot must rely on upward tain waves with findings that have made flying motion of the air. safer for all pilots. However, soaring is primarily To a sailplane pilot, "lift" means the rate of recreational. climb he can achieve in an up-current, while "sink" A sailplane must have auxiliary power to be denotes his rate of descent in a downdraft or in come airborne such as a winch, a ground tow, or neutral air. "Zero sink" means that upward cur a tow by a powered aircraft. Once the sailcraft is rents are just strong enough to enable him to hold airborne and the tow cable released, performance altitude but not to climb. Sailplanes are highly 171 r efficient machines; a sink rate of a mere 2 feet per second. There is no point in trying to soar until second provides an airspeed of about 40 knots, and weather conditions favor vertical speeds greater a sink rate of 6 feet per second gives an airspeed than the minimum sink rate of the aircraft. -

Thesis Characteristics of Hailstorms and Enso

THESIS CHARACTERISTICS OF HAILSTORMS AND ENSO-INDUCED EXTREME STORM VARIABILITY IN SUBTROPICAL SOUTH AMERICA Submitted by Zachary S. Bruick Department of Atmospheric Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Spring 2019 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Kristen L. Rasmussen Russ S. Schumacher V. Chandrasekar Copyright by Zachary S. Bruick 2019 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT CHARACTERISTICS OF HAILSTORMS AND ENSO-INDUCED EXTREME STORM VARIABILITY IN SUBTROPICAL SOUTH AMERICA Convection in subtropical South America is known to be among the strongest anywhere in the world. Severe weather produced from these storms, including hail, strong winds, tornadoes, and flash flooding, causes significant damages to property and agriculture within the region. These in- sights are only due to the novel observations produced by the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite since there are the limited ground-based observations within this region. Con- vection is unique in subtropical South America because of the synoptic and orographic processes that support the initiation and maintenance of convection here. Warm and moist air is brought into the region by the South American low-level jet from the Amazon. When the low-level jet intersects the Andean foothills and Sierras de Córdoba, this unstable air is lifted along the orography. At the same time, westerly flow subsides in the lee of the Andes, which provides a capping inversion over the region. When the orographic lift is able to erode the subsidence inversion, convective initiation occurs and strong thunderstorms develop. As a result, convection is most frequent near high terrain. -

Exploring the MBL Cloud and Drizzle Microphysics Retrievals from Satellite, Surface and Aircraft

Exploring the MBL cloud and drizzle microphysics retrievals from satellite, surface and aircraft Xiquan Dong, University of Arizona Pat Minnis, SSAI 1. Briefly describe our 2. Can we utilize these surface newly developed retrieval retrievals to develop cloud (and/or drizzle) Re profile for algorithm using ARM radar- CERES team? lidar, and comparison with aircraft data. Re is a critical for radiation Wu et al. (2020), JGR and aerosol-cloud- precipitation interactions, as well as warm rain process. 1 A long-term Issue: CERES Re is too large, especially under drizzling MBL clouds A/C obs in N Atlantic • Cloud droplet size retrievals generally too high low clouds • Especially large for Re(1.6, 2.1 µm) CERES Re too large Worse for larger Re • Cloud heterogeneity plays a role, but drizzle may also be a factor - Can we understand the impact of drizzle on these NIR retrievals and their differences with Painemal et al. 2020 ground truth? A/C obs in thin Pacific Sc with drizzle CERES LWP high, tau low, due to large Re Which will lead to high SW transmission at the In thin drizzlers, Re is overestimated by 3 µm surface and less albedo at TOA Wood et al. JAS 2018 Painemal et al. JGR 2017 2 Profiles of MBL Cloud and Drizzle Microphysical Properties retrieved from Ground-based Observations and Validated by Aircraft data during ACE-ENA IOP 푫풎풂풙 ퟔ Radar reflectivity: 풁 = ퟎ 푫 푵풅푫 Challenge is to simultaneously retrieve both cloud and drizzle properties within an MBL cloud layer using radar-lidar observations because radar reflectivity depends on the sixth power of the particle size and can be highly weighted by a few large drizzle drops in a drizzling cloud 3 Wu et al. -

7.2 DEVELOPMENT of a METEOROLOGICAL PARTICLE SENSOR for the OBSERVATION of DRIZZLE Richard Lewis* National Weather Service St

7.2 DEVELOPMENT OF A METEOROLOGICAL PARTICLE SENSOR FOR THE OBSERVATION OF DRIZZLE Richard Lewis* National Weather Service Sterling, VA 20166 Stacy G. White Science Applications International Corporation Sterling, VA 20166 1. INTRODUCTION “Very small, numerous, and uniformly dispersed, water drops that may appear to float while The National Weather Service (NWS) and Federal following air currents. Unlike fog droplets, drizzle Aviation Administration (FAA) are jointly participating in a falls to the ground. It usually falls from low Product Improvement Program to improve the capabilities stratus clouds and is frequently accompanied by of the of Automated Surface Observing Systems (ASOS). low visibility and fog. The greatest challenge in the ASOS was to automate the visual elements of the observation; sky conditions, visibility In weather observations, drizzle is classified as and type of weather. Despite achieving some success in (a) “very light”, comprised of scattered drops that this area, limitations in the reporting capabilities of the do not completely wet an exposed surface, ASOS remain. As currently configured, the ASOS uses a regardless of duration; (b) “light,” the rate of fall Precipitation Identifier that can only identify two being from a trace to 0.25 mm per hour: (c) precipitation types, rain and snow. A goal of the Product “moderate,” the rate of fall being 0.25-0.50 mm Improvement program is to replace the current PI sensor per hour:(d) “heavy” the rate of fall being more with one that can identify additional precipitation types of than 0.5 mm per hour. When the precipitation importance to aviation. Highest priority is being given to equals or exceeds 1mm per hour, all or part of implementing capabilities of identifying ice pellets and the precipitation is usually rain; however, true drizzle. -

Exhibit 18 Ro-6-151

EXHIBIT 18 RO-6-151 1921 University Ave. ▪ Berkeley, CA 94704 ▪ Phone 510-629-4930 ▪ Fax 510-550-2639 Chris Lautenberger [email protected] 12 April 2018 Dan Silver, Executive Director Endangered Habitats League 8424 Santa Monica Blvd., Suite A 592 Los Angeles, CA 90069-4267 Subject: Fire risk impacts of Otay Ranch Village 14 and Planning Areas 16/19 Project Dear Mr. Silver, At your request I have reviewed the Fire Protection Plan (FPP) for the planned Otay Ranch Village 14 and Planning Areas 16/19 Project and analyzed potential fire/life safety impacts of this planned development. Santa Ana winds Santa Ana winds (or Santa Anas for short) present major fire/life safety concerns for the Otay Ranch Village 14 and Planning Areas 16/19 Project. Santa Anas are hot and dry winds that blow through Southern California each year, usually between the months of October and April. Santa Anas occur when high pressure forms in the Great Basin (Western Utah, much of Nevada, and the Eastern border of California) with lower pressure off the coast of Southern California. This pressure gradient drives airflow toward the Pacific Ocean. As air travels West from the Great Basin, orographic lift dries the air as it rises in elevation over mountain ranges. As air descends from high elevations in the Sierra Nevada, its temperature rises dramatically (~5 °F per 1000 ft decrease in elevation). A subsequent drop in relative humidity accompanies this rise in temperature. This drying/heating phenomenon is known as a katabatic wind. Relative humidity in Southern California during Santa Anas is often 10% or lower. -

Influence of Orographic Precipitation on the Co-Evolution of Landforms and Vegetation

EGU2020-5280, updated on 26 Sep 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu2020-5280 EGU General Assembly 2020 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Influence of orographic precipitation on the co-evolution of landforms and vegetation Ankur Srivastava1, Omer Yetemen2, Nikul Kumari1, and Patricia M. Saco1 1University of Newcastle, University of Newcastle, Civil and Environmental Engineering, Callaghan, Australia ([email protected]) 2Eurasia Institute of Earth Sciences, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey Topography plays an important role in controlling the amount and the spatial distribution of precipitation due to orographic lift mechanisms. Thus, it affects the existing climate and vegetation distribution. Recent landscape modelling efforts show how the orographic effects on precipitation result in the development of asymmetric topography. However, these modelling efforts do not include vegetation dynamics that inhibits sediment transport. Here, we use the CHILD landscape evolution model (LEM) coupled with a vegetation dynamics component that explicitly tracks above- and below-ground biomass. We ran the model under three scenarios. A spatially‑uniform precipitation scenario, a scenario with increasing rainfall as a function of elevation, and another one that includes rain shadow effects in which leeward hillslopes receive less rainfall than windward ones. Preliminary results of the model show that competition between increased shear stress due to increased runoff and vegetation protection affects the shape of the catchment. Hillslope asymmetry between polar- and equator-facing hillslopes is enhanced (diminished) when rainfall coincides with a windward (leeward) side of the mountain range. It acts to push the divide (i.e., the boundary between leeward and windward flanks) and leads to basin reorganization through reach capture. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

Evaluation of Satellite Rainfall Estimates for Drought and Flood Monitoring in Mozambique

Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 1758-1776; doi:10.3390/rs70201758 OPEN ACCESS remote sensing ISSN 2072-4292 www.mdpi.com/journal/remotesensing Article Evaluation of Satellite Rainfall Estimates for Drought and Flood Monitoring in Mozambique Carolien Toté 1,*, Domingos Patricio 2, Hendrik Boogaard 3, Raymond van der Wijngaart 3, Elena Tarnavsky 4 and Chris Funk 5 1 Flemish Institute for Technological Research (VITO), Remote Sensing Unit, Boeretang 200, 2400 Mol, Belgium 2 Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia (INAM), Rua de Mukumbura 164, C.P. 256, Maputo, Mozambique; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Alterra, Wageningen University, PO Box 47, 3708PB Wageningen, The Netherlands; E-Mails: [email protected] (H.B.); [email protected] (R.W.) 4 Department of Meteorology, University of Reading, Earley Gate, PO Box 243, Reading RG6 6BB, UK; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 United States Geological Survey/Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center and the Climate Hazard Group, Geography Department, University of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-14-336844; Fax: +32-14-322795. Academic Editor: George P. Petropoulos and Prasad S. Thenkabail Received: 8 August 2014 / Accepted: 29 January 2015 / Published: 5 February 2015 Abstract: Satellite derived rainfall products are useful for drought and flood early warning and overcome the problem of sparse, unevenly distributed and erratic rain gauge observations, provided their accuracy is well known. Mozambique is highly vulnerable to extreme weather events such as major droughts and floods and thus, an understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of different rainfall products is valuable. -

Print Key. (Pdf)

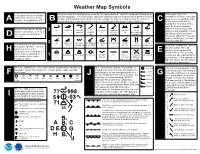

Weather Map Symbols Along the center, the cloud types are indicated. The top symbol is the high-level cloud type followed by the At the upper right is the In the upper left, the temperature mid-level cloud type. The lowest symbol represents low-level cloud over a number which tells the height of atmospheric pressure reduced to is plotted in Fahrenheit. In this the base of that cloud (in hundreds of feet) In this example, the high level cloud is Cirrus, the mid-level mean sea level in millibars (mb) A example, the temperature is 77°F. B C C to the nearest tenth with the cloud is Altocumulus and the low-level clouds is a cumulonimbus with a base height of 2000 feet. leading 9 or 10 omitted. In this case the pressure would be 999.8 mb. If the pressure was On the second row, the far-left Ci Dense Ci Ci 3 Dense Ci Cs below Cs above Overcast Cs not Cc plotted as 024 it would be 1002.4 number is the visibility in miles. In from Cb invading 45° 45°; not Cs ovcercast; not this example, the visibility is sky overcast increasing mb. When trying to determine D whether to add a 9 or 10 use the five miles. number that will give you a value closest to 1000 mb. 2 As Dense As Ac; semi- Ac Standing Ac invading Ac from Cu Ac with Ac Ac of The number at the lower left is the a/o Ns transparent Lenticularis sky As / Ns congestus chaotic sky Next to the visibility is the present dew point temperature. -

California Cumulonimbus

California Cumulonimbus Spring 2015 Articles in this Edition: Welcome Message by Jimmy Taeger California CoCoRaHS Regions CoCoRaHS, which stands for Welcome Message 1 lowers are in bloom and the Community Collaborative Rain Northern Mountains F San Joaquin Valley days are getting longer which Hail and Snow network, is a S. Coast - Los Angeles means...it’s time for another edi- group of volunteer observers who S. Coast - San Diego tion of the California Cumulo- report precipitation daily. Not Observer 1 S. Deserts - Vegas Region nimbus! The California Cumulo- only is it fun, but your report Spotlight: Bob SE. Deserts - nimbus is a biannual newsletter gives vital information to organi- Phoenix Region King for California CoCoRaHS ob- zations and individuals such as servers that is issued twice a year; the National Weather Service, once in the spring and once in the River Forecast Centers, farmers, fall. and others. Low Elevation 2 This edition contains articles on Visit cocorahs.org to sign up, or Snow in SoCal the summer climate outlook, an e-mail [email protected] observer spotlight, a low eleva- for additional information. Central Coast tion snow weather event in E. Sierra N. Coast SoCal, the El Niño advisory, the Enjoy the newsletter! Northern Interior continuing California drought California’s 3 and spring in the North Bay area. Summer Climate Map of California divided up into different CoCoRaHS regions. Each Outlook region has one or more coordinators. If you’re not a CoCoRaHS volun- (Source: CoCoRaHS) teer yet, it’s not too late to join! Observer Spotlight: Bob King by Jimmy Taeger El Niño Advisory 3 in Effect of the daily observations, especial- S ince 2009, Bob King has been ly since the gauge was just 20 feet an active and loyal observer to from his bedroom door. -

Towards the Improvement of Winter Orographic Cloud Seeding in Utah

TOWARDS THE IMPROVEMENT OF WINTER OROGRAPHIC CLOUD SEEDING IN UTAH Prepared for: Utah Division of Water Resources www. https://water.utah.gov/ Prepared by: The Utah Climate Center December 2019 www.climate.usu.edu Phone: (435) 797-2190 Dr. Binod Pokharel Post-Doctoral Research Scientist, Utah Climate Center Utah State University Prof. Simon Wang, Utah State University & Utah Climate Center Dr. Jon Meyer, Utah Climate Center Dr. Hongping Gu, Utah Climate Center Prof. Matthew LaPlante Utah State University i NOTICE This report was compiled by the Utah Climate Center. The results and conclusions in this report are based on industry-accepted best practices and publicly available data sources. Therefore, neither the Utah Climate Center nor any person acting on behalf of the Utah Climate Center can: (a) make any warranty, expressed or implied, regarding future use of any information or method in this report, or (b) assume any future liability regarding the use of any information or method contained in this report. The funding for this study is provided by the Utah Division of Water Resources, the State of Utah, and the Colorado River Lower Basin States. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS .............................................................................................................. iii LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................................v LIST OF TABLES ..................................................................................................................... -

Name That Cloud!

Period _____ Name ___________________________ Name That Cloud! What’s the weather going to be like today? We’re always asking that. We need to know. The weather affects what we wear, what we need to take with us, and what we do. Will we need to wear shorts, or a sweater and warm pants? Will we need to take an umbrella or a heavy coat? Can we play outside after school? You can learn to predict the weather. You don’t need a lot of equipment or fancy stuff – just use your eyes! Go outside and look at the clouds. Clouds come in different shapes, sizes, and colors. You can use what you know about clouds to find out what the weather will bring. Okay, here’s what you need to know about clouds. Clouds are named by the way they look. We use Latin root words to name them. Clouds come in different sizes and shapes. They are formed and drift along at different heights in the sky. All of these things help us name them and know what kind of weather they may bring. There are three main types of clouds: cumulus, cirrus, and stratus. When the weather is fair, we see cumulus clouds. Fair weather is fine, sunny weather with no chance of rain, snow, or any other precipitation. Cumulus clouds are white, puffy clouds that may look like cauliflower. In Latin, cumulus means “heap.” You may see heaps and heaps of these white, fluffy, cotton-ball-looking clouds. Usually there are large spaces of clear blue sky in between them.