Appalachia Winter/Spring 2019: Complete Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer 2004 Vol. 23 No. 2

Vol 23 No 2 Summer 04 v4 4/16/05 1:05 PM Page i New Hampshire Bird Records Summer 2004 Vol. 23, No. 2 Vol 23 No 2 Summer 04 v4 4/16/05 1:05 PM Page ii New Hampshire Bird Records Volume 23, Number 2 Summer 2004 Managing Editor: Rebecca Suomala 603-224-9909 X309 [email protected] Text Editor: Dorothy Fitch Season Editors: Pamela Hunt, Spring; William Taffe, Summer; Stephen Mirick, Fall; David Deifik, Winter Layout: Kathy McBride Production Assistants: Kathie Palfy, Diane Parsons Assistants: Marie Anne, Jeannine Ayer, Julie Chapin, Margot Johnson, Janet Lathrop, Susan MacLeod, Dot Soule, Jean Tasker, Tony Vazzano, Robert Vernon Volunteer Opportunities and Birding Research: Susan Story Galt Photo Quiz: David Donsker Where to Bird Feature Coordinator: William Taffe Maps: William Taffe Cover Photo: Juvenile Northern Saw-whet Owl, by Paul Knight, June, 2004, Francestown, NH. Paul watched as it flew up with a mole in its talons. New Hampshire Bird Records (NHBR) is published quarterly by New Hampshire Audubon (NHA). Bird sightings are submitted to NHA and are edited for publication. A computerized print- out of all sightings in a season is available for a fee. To order a printout, purchase back issues, or volunteer your observations for NHBR, please contact the Managing Editor at 224-9909. Published by New Hampshire Audubon New Hampshire Bird Records © NHA April, 2005 Printed on Recycled Paper Vol 23 No 2 Summer 04 v4 4/16/05 1:05 PM Page 1 Table of Contents In This Issue Volunteer Request . .2 A Checklist of the Birds of New Hampshire—Revised! . -

August 01, 2013

VOLUME 38, NUMBER 9 AUGUST 1, 2013 FREE THE WEEKLY NEWS & LIFESTYLE JOURNAL OF MT. WASHINGTON VALLEY Guiided Tours Daiilly or Driive Your Own Car Biking Kayaking Hiking Outfitters Shop Glen View Café Kids on Bikes Nooks & Crannies Racing Family Style Great views in the Page 23 Zealand Valley Page 22 Rt. 16, Pinkham Notch www.mtwashingtonautoroad.com A SALMON PRESS PUBLICATION • (603) 447-6336 • PUBLISHED IN CONWAY, NH (603) 466-3988 News/Round-Ups Arts Jubilee continues its 31st summer concert season NORTH CONWAY playing around having a good be hosted by the valley’s own — Arts Jubilee begins the time into a band that has theatrical celebrity, George month of August with the first gained notoriety as one of the Cleveland and will open with of two remaining concerts in Valley’s well known groups. the vocal/instrumental duo, the 31st summer concert sea- Starting off in the après mu- Dennis & Davey - whose mu- son, presenting high energy, sic scene, Rek’lis has played sic is known throughout the world-class performers per- at numerous venues through- area as the next best thing to forming a wide range of enter- out the area. With over 60 visiting the Emerald Isle. tainment hosted at Cranmore years combined experience Arts Jubilee’s outdoor festi- Mountain, North Conway. they are known to please the val concerts are found at the Music that has stood the crowd with an eclectic mix of base of the North Slope at test of time will take the spot- 80’s, punk rock and new wave Cranmore Mountain in North light on Thursday, Aug. -

Exploring the MBL Cloud and Drizzle Microphysics Retrievals from Satellite, Surface and Aircraft

Exploring the MBL cloud and drizzle microphysics retrievals from satellite, surface and aircraft Xiquan Dong, University of Arizona Pat Minnis, SSAI 1. Briefly describe our 2. Can we utilize these surface newly developed retrieval retrievals to develop cloud (and/or drizzle) Re profile for algorithm using ARM radar- CERES team? lidar, and comparison with aircraft data. Re is a critical for radiation Wu et al. (2020), JGR and aerosol-cloud- precipitation interactions, as well as warm rain process. 1 A long-term Issue: CERES Re is too large, especially under drizzling MBL clouds A/C obs in N Atlantic • Cloud droplet size retrievals generally too high low clouds • Especially large for Re(1.6, 2.1 µm) CERES Re too large Worse for larger Re • Cloud heterogeneity plays a role, but drizzle may also be a factor - Can we understand the impact of drizzle on these NIR retrievals and their differences with Painemal et al. 2020 ground truth? A/C obs in thin Pacific Sc with drizzle CERES LWP high, tau low, due to large Re Which will lead to high SW transmission at the In thin drizzlers, Re is overestimated by 3 µm surface and less albedo at TOA Wood et al. JAS 2018 Painemal et al. JGR 2017 2 Profiles of MBL Cloud and Drizzle Microphysical Properties retrieved from Ground-based Observations and Validated by Aircraft data during ACE-ENA IOP 푫풎풂풙 ퟔ Radar reflectivity: 풁 = ퟎ 푫 푵풅푫 Challenge is to simultaneously retrieve both cloud and drizzle properties within an MBL cloud layer using radar-lidar observations because radar reflectivity depends on the sixth power of the particle size and can be highly weighted by a few large drizzle drops in a drizzling cloud 3 Wu et al. -

In This Issue: Saturday, November 3 Highland Center, Crawford Notch, NH from the Chair

T H E O H A S S O C I A T I O N 17 Brenner Drive, Newton, New Hampshire 03858 The O H Association is former employees of the AMC Huts System whose activities include sharing sweet White Mountain memories. 2018 Fall Reunion In This Issue: Saturday, November 3 Highland Center, Crawford Notch, NH From the Chair .......... 2 Poetry & Other Tidbits .......... 3 1pm: Hike up Mt. Avalon, led by Doug Teschner (meet Fall Fest Preview .......... 4 at Highland Center Fastest Known Times (FKTs) .......... 6 3:30-4:30pm: Y-OH discussion session led by Phoebe “Adventure on Katahdin” .......... 9 Howe. Be part of the conversation on growing the OHA Cabin Photo Project Update .......... 10 younger and keeping the OHA relevant in the 21st 2019 Steering Committee .......... 11 century. Meet in Thayer Hall. OHA Classifieds .......... 12 4:30-6:30pm: Acoustic music jam! Happy Hour! AMC “Barbara Hull Richardson” .......... 13 Library Open House! Volunteer Opportunities .......... 16 6:30-7:30pm: Dinner. Announcements .......... 17 7:45-8:30pm: Business Meeting, Awards, Announce- Remember When... .......... 18 ments, Proclamations. 2018 Fall Croos .......... 19 8:30-9:15pm: Featured Presentation: “Down Through OHA Merchandise .......... 19 the Decades,” with Hanque Parker (‘40s), Tom Deans Event News .......... 20 (‘50s), Ken Olsen (‘60s), TBD (‘70s), Pete & Em Benson Gormings .......... 21 (‘80s), Jen Granducci (‘90s), Miles Howard (‘00s), Becca Obituaries .......... 22 Waldo (‘10s). “For Hannah & For Josh” .......... 24 9:15-9:30pm: Closing Remarks & Reminders Trails Update .......... 27 Submission Guidelines .......... 28 For reservations, call the AMC at 603-466-2727. Group # 372888 OH Reunion Dinner, $37; Rooms, $73-107. -

7.2 DEVELOPMENT of a METEOROLOGICAL PARTICLE SENSOR for the OBSERVATION of DRIZZLE Richard Lewis* National Weather Service St

7.2 DEVELOPMENT OF A METEOROLOGICAL PARTICLE SENSOR FOR THE OBSERVATION OF DRIZZLE Richard Lewis* National Weather Service Sterling, VA 20166 Stacy G. White Science Applications International Corporation Sterling, VA 20166 1. INTRODUCTION “Very small, numerous, and uniformly dispersed, water drops that may appear to float while The National Weather Service (NWS) and Federal following air currents. Unlike fog droplets, drizzle Aviation Administration (FAA) are jointly participating in a falls to the ground. It usually falls from low Product Improvement Program to improve the capabilities stratus clouds and is frequently accompanied by of the of Automated Surface Observing Systems (ASOS). low visibility and fog. The greatest challenge in the ASOS was to automate the visual elements of the observation; sky conditions, visibility In weather observations, drizzle is classified as and type of weather. Despite achieving some success in (a) “very light”, comprised of scattered drops that this area, limitations in the reporting capabilities of the do not completely wet an exposed surface, ASOS remain. As currently configured, the ASOS uses a regardless of duration; (b) “light,” the rate of fall Precipitation Identifier that can only identify two being from a trace to 0.25 mm per hour: (c) precipitation types, rain and snow. A goal of the Product “moderate,” the rate of fall being 0.25-0.50 mm Improvement program is to replace the current PI sensor per hour:(d) “heavy” the rate of fall being more with one that can identify additional precipitation types of than 0.5 mm per hour. When the precipitation importance to aviation. Highest priority is being given to equals or exceeds 1mm per hour, all or part of implementing capabilities of identifying ice pellets and the precipitation is usually rain; however, true drizzle. -

6–8–01 Vol. 66 No. 111 Friday June 8, 2001 Pages 30801–31106

6–8–01 Friday Vol. 66 No. 111 June 8, 2001 Pages 30801–31106 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 19:13 Jun 07, 2001 Jkt 194001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\08JNWS.LOC pfrm04 PsN: 08JNWS 1 II Federal Register / Vol. 66, No. 111 / Friday, June 8, 2001 The FEDERAL REGISTER is published daily, Monday through SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Friday, except official holidays, by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, PUBLIC Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Act (44 U.S.C. Subscriptions: Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Committee of Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Superintendent of Assistance with public subscriptions 512–1806 Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official edition. General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 Single copies/back copies: The Federal Register provides a uniform system for making available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Paper or fiche 512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and Assistance with public single copies 512–1803 Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published Subscriptions: by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Paper or fiche 523–5243 Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 523–5243 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

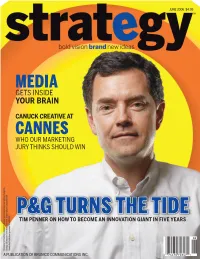

P&G Turns the Tide

MEDIA GETS INSIDE YOUR BRAIN CANUCK CREATIVE AT CANNES WHO OUR MARKETING JURY THINKS SHOULD WIN PP&G&G TTURNSURNS TTHEHE TTIDEIDE TIM PENNER ON HOW TO BECOME AN INNOVATION GIANT IN FIVE YEARS CCover.Jun06.inddover.Jun06.indd 1 55/18/06/18/06 112:13:102:13:10 PPMM SST.6637.TaylorGeorge.dps.inddT.6637.TaylorGeorge.dps.indd 2 55/18/06/18/06 44:23:10:23:10 PMPM taylor george SERVICES OFFERED: Taylor George began operations in the fall of 1995 as a General Agency/AOR two-person design studio. Over the next several years the company grew to a full service agency with a staff of Direct Agency 20. In 2003, Taylor George co founded BRAVE Strategy, Interactive Agency a creative and strategic boutique with expertise in tar- Public Relations Agency geting Canada's diverse Aboriginal population. Design Agency Taylor George and BRAVE are headquartered in Winnipeg, Media Agency Manitoba. The agencies have a sales office in Toronto and will be opening a Vancouver office in July of 2006. “Our approach is all about stories. Stories affect people. APTN Program Guide. Recent national campaigns for Stories APTN have substantially increased audience numbers create emotion. Stories get a response.” Peter George TelPay B-to-B magazine campaign. TelPay President has achieved significant growth since being rebranded by TG in 2005. Subscription Brochure, Manitoba Opera. Season campaign for Manitoba Opera increased subscriptions 28% over the previous year. CLIENT LIST KEY PERSONNEL CONTACT US. 1. Aboriginal People's 12. TelPay Peter George, President and CEO, Taylor George/BRAVE Strategy Television Network 13. -

North Carolina STATE PARKS

North Carolina STATE PARKS North Carolina Department of Conservation and Development Division of State Parks North Carolina State Parks A guide to the areas set aside and maintained taining general information about the State as State Parks for the enjoyment of North Parks as a whole and brief word-and-picture Carolina's citizens and their guests — con- descriptions of each. f ) ) ) ) YOUR STATE PARKS THE STATE PARKS described in this well planned, well located, well equipped and booklet are the result of planning and well maintained State Parks are a matter of developing over a number of years. justifiable pride in which every citizen has Endowed by nature with ideal sites that a share. This is earned by your cooperation range from the shores of the Atlantic Ocean in observing the lenient rules and leaving the to the tops of the Blue Ridge Mountains, facilities and grounds clean and orderly. the State has located its State Parks for easy Keep this guide book for handy reference- access as well as for varied appeal. They use your State Parks year 'round for health- offer a choice of homelike convenience and ful recreation and relaxation! comfort in sturdy, modern facilities . the hardy outdoor life of tenting and camp cook- Amos R. Kearns, Chairman ing ... or the quick-and-easy freedom of a Hugh M. Morton, Vice Chairman day's picnicking. The State Parks offer excel- Walter J. Damtoft lent opportunities for economical vacations— Eric W. Rodgers either in the modern, fully equipped vacation Miles J. Smith cabins or in the campgrounds. -

Insight September 2019

Monthly Newsletter September 2019 September INSIDE THIS ISSUE The Art of Global Warming IFRS Survey Results 2 UPCOMING EVENTS Environment 3-4 IFRS17 Program Update Forum Technology 5 Sunsystems Q&A Webinar Millennium News 6-8 Economy 9-10 1 IFRS17 PROGRAM UPDATE SURVEY During July and August 2019, an online survey was conducted by Millennium Consulting which asked international insurance companies questions about their IFRS 17 compliance programs. Participants. Participants included Finance Directors, Chief Actuaries, IT Directors and Senior Risk Managers. Participating regions. A large response was received from insurers in the following countries: UK, Netherlands, Germany, Ireland, Switzerland, Morocco, Mexico, Hong Kong, China, Thailand, Taiwan and Australia. Significant outcomes • As expected, IFRS 17 compliance was identified as being primarily the responsibility of the Finance department although 47% of the responses suggested that it was a joint Finance, Actuarial, IT, Risk and Underwriting responsibility. • Compliance is managed centrally by almost 70% of the participants with only 28% having autonomy to implement their own local solutions. • 9% of respondents indicated that pure IFRS 17 compliance was their primary goal whilst 36% stated it was a catalyst for a broader Finance Transformation program. • 31% of the respondents reported that their IFRS 17 implementations were underway whereas 39% were still working on the detailed design. • Confidence in achieving IFRS 17 compliance within the current time scales is high with only 9% suggesting it would not be possible. • SAS was identified as the most popular technology for CSM calculation with 17% of the respondents having selected it. • The primary area of concern relates to data with 20% identifying data integration as of greatest concern. -

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities Alaska Aialik Bay Alaska Highway Alcan Highway Anchorage Arctic Auk Lake Cape Prince of Wales Castle Rock Chilkoot Pass Columbia Glacier Cook Inlet Copper River Cordova Curry Dawson Denali Denali National Park Eagle Fairbanks Five Finger Rapids Gastineau Channel Glacier Bay Glenn Highway Haines Harding Gateway Homer Hoonah Hurricane Gulch Inland Passage Inside Passage Isabel Pass Juneau Katmai National Monument Kenai Kenai Lake Kenai Peninsula Kenai River Kechikan Ketchikan Creek Kodiak Kodiak Island Kotzebue Lake Atlin Lake Bennett Latouche Lynn Canal Matanuska Valley McKinley Park Mendenhall Glacier Miles Canyon Montgomery Mount Blackburn Mount Dewey Mount McKinley Mount McKinley Park Mount O’Neal Mount Sanford Muir Glacier Nome North Slope Noyes Island Nushagak Opelika Palmer Petersburg Pribilof Island Resurrection Bay Richardson Highway Rocy Point St. Michael Sawtooth Mountain Sentinal Island Seward Sitka Sitka National Park Skagway Southeastern Alaska Stikine Rier Sulzer Summit Swift Current Taku Glacier Taku Inlet Taku Lodge Tanana Tanana River Tok Tunnel Mountain Valdez White Pass Whitehorse Wrangell Wrangell Narrow Yukon Yukon River General Views—no specific location Alabama Albany Albertville Alexander City Andalusia Anniston Ashford Athens Attalla Auburn Batesville Bessemer Birmingham Blue Lake Blue Springs Boaz Bobler’s Creek Boyles Brewton Bridgeport Camden Camp Hill Camp Rucker Carbon Hill Castleberry Centerville Centre Chapman Chattahoochee Valley Cheaha State Park Choctaw County -

Samsung Galaxy Note9 N960U User Manual

User manual Table of contents Special features 1 Add an email account 12 Getting started 3 Transfer data from your old device 12 Front and back views 4 Set up your voicemail 14 Navigation 15 Assemble your device 5 Navigation bar 18 Install a SIM card and memory card 6 Home screen 20 Charge the battery 6 Customize your Home screen 21 S Pen 8 Status bar 27 Start using your device 10 Notification panel 29 Use the Setup Wizard 10 S Pen functions 32 Lock or unlock your device 11 Edge screen 42 Add a Google account 11 Bixby 48 Add a Samsung account 12 i GEN_N960U_EN_UM_TN_RG6_080918_FINAL Always On Display 50 Samsung apps 70 Flexible security 51 Calculator 70 Multi window 57 Calendar 72 Enter text 59 Camera and video 75 Emergency mode 62 Clock 81 Apps 64 Contacts 85 Using apps 65 Email 92 Access apps 65 Galaxy Apps 95 Add an apps shortcut 65 Gallery 96 Search for apps 66 Internet 101 Galaxy Essentials 66 Messages 105 Uninstall or disable apps 66 My Files 107 Sort apps 67 PENUP 109 Create and use folders 67 Phone 110 App settings 68 Samsung Gear 121 ii Samsung Health 122 Play Music 134 Samsung Notes 124 Play Store 134 Samsung Pay 126 YouTube 135 Samsung+ 128 Settings 136 SmartThings 130 Access Settings 137 Secure Folder 131 Search for Settings 137 Google apps 133 Connections 138 Chrome 133 Wi-Fi 138 Drive 133 Bluetooth 141 Duo 133 Phone visibility 143 Gmail 133 Data usage 143 Google 133 Airplane mode 144 Maps 134 NFC and payment 144 Photos 134 Mobile hotspot 145 Play Movies & TV 134 Tethering 148 iii Location 148 Key-tap feedback 158 Nearby device -

Ysu1311869143.Pdf (795.38

THIS IS LIFE: A Love Story of Friendship by Annie Murray Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of M.F.A. in the NEOMFA Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2011 THIS IS LIFE: A Love Story of Friendship Annie Murray I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: ________________________________________________________ Annie Murray, Student Date Approvals: ________________________________________________________ David Giffels, Thesis Advisor Date ________________________________________________________ Phil Brady, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________ Mary Biddinger, Committee Member Date ________________________________________________________ Peter J. Kasvinsky, Dean, School of Graduate Studies and Research Date © A. Murray 2011 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the universal journey of self discovery against the specific backdrop of the south coast of England where the narrator, an American woman in her early twenties, lives and works as a barmaid with her female travel companion. Aside from outlining the journey from outsider to insider within a particular cultural context, the thesis seeks to understand the implications of a defining friendship that ultimately fails, the ways a young life is shaped through travel and loss, and the sacrifices a person makes when choosing a place to call home. The thesis follows the narrator from her initial departure for England at the age of twenty-two through to her final return to Ohio at the age of twenty-seven, during which time the friendship with the travel companion is dissolved and the narrator becomes a wife and a mother.