Susan Foister

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nineteenth(Century!British!Perspectives!!

! ! NINETEENTH(CENTURY!BRITISH!PERSPECTIVES!! ON!EARLY!GERMAN!PAINTINGS:! THE!CASE!OF!THE!KRÜGER!COLLECTION! AT!THE!NATIONAL!GALLERY!AND!BEYOND! ! ! TWO!VOLUMES! ! ! VOLUME!I! ! ! ! ! NICOLA!SINCLAIR! ! ! ! PH.D.! ! ! ! UNIVERSITY!OF!YORK! ! ! HISTORY!OF!ART! ! ! MARCH!2016! ! ! ! 1! ABSTRACT' ! ! This!study!examines!the!British!receptiOn!Of!early!German!painting!in!the! nineteenth!century!thrOugh!the!case!study!Of!the!Krüger!acquisitiOn!fOr!the!NatiOnal! Gallery!in!1854.!It!prOvides!new!infOrmatiOn!about!why!this!cOllectiOn!Of! predOminantly!religiOus!fifteenth(!and!sixteenth(century!paintings!frOm!COlOgne!and! Westphalia!was!acquired!and!hOw!it!was!evaluated,!displayed!and!distributed!in!British! public!and!private!cOllections,!against!a!backdrop!of!midcentury!develOpments!in! British!public!displays!Of!art,!art(historical!literature,!private!collecting!and!the!art! market.!!! ! In!light!Of!lOng(held!perceptions!that!the!acquisition!was!a!mistake!and!that!the! paintings!were!inferiOr!to!early!wOrks!frOm!Italy!and!the!Netherlands,!this!study!Offers! an!alternative!perspective!that!it!was!an!enterprising!attempt!tO!implement!new! models!Of!histOrical!display!in!natiOnal!cOllectiOns,!and!tO!ratiOnalise!hOw!suppOsedly! inferior!paintings!cOuld!have!value!in!public!and!private!cOllectiOns.!By!loOking!at!the! way!these!rediscOvered!German!paintings!were!evaluated,!this!study!advances! understanding!Of!hOw!ROmantic,!schOlarly!and!fOrmal!mOdels!fOr!reexamining!early! paintings!Overlapped,!cOnflicted!and!changed!in!the!nineteenth!century.!The!Krüger! -

Renaissance Studies

398 Reviews of books Denley observes that the history of the Studio dominates not only the historiography of education in Siena but also the documentary series maintained by various councils and administrators in the late medieval and Renaissance eras. The commune was much more concerned about who taught what at the university level than at the preparatory level. Such an imbalance is immediately evident when comparing the size of Denley’s own two studies. Nevertheless, he has provided a useful introduction to the role of teachers in this important period of intellectual transition, and the biographical profiles will surely assist other scholars working on Sienese history or the history of education. University of Massachusetts-Lowell Christopher Carlsmith Christopher S. Wood, Forgery, Replica, Fiction: Temporalities of German Renaissance Art. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2008. 416 pp. 116 black and white illustrations. Cloth $55.00. ISBN 022-6905977 (hb). Did Germany have a Renaissance? The answer depends, of course, on one’s definition of Renaissance; whether one sees it mainly as an era of rebirth of the arts in imitation of the masters of classical antiquity or not. In Germany, the Romans stayed only in part of what is now the Bundesrepublik Deutschland, while a large Germania Libera (as the Romans called it) continued with her rustic but wholesome customs described by Tacitus as an example to his fellow countrymen. The Roman influence on Germanic lifestyle was limited and transitory and therefore a rebirth of classical antiquity could only be a complicated one. Not even the Italian peninsula had a homogeneous Roman antiquity (and it would be difficult to give precise chronological and geographical definitions of antiquity per se) but in the case of German Renaissance art the potential models needed to be explored in depth and from an extraneous vantage point. -

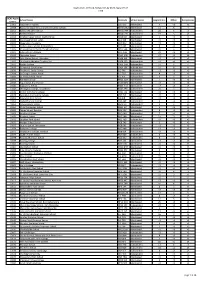

Undergraduate Admissions by

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2019 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 6 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 14 3 <3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 18 4 3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <3 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 10 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 20 3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 25 6 5 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 4 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 3 3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 17 10 6 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent 3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 10 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 38 14 12 10046 Didcot Sixth Form OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained 5 <3 <3 10050 Desborough College SL6 2QB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10051 Newlands Girls' School SL6 5JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10053 Oxford Sixth Form College OX1 4HT Independent 3 <3 -

Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 3 Issue 3 2012 Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture (Volume 3, Issue 3) Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation . "Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture (Volume 3, Issue 3)." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 3, 3 (2012). https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol3/iss3/20 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. et al. Welcome Welcome to this issue of Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art & Architecture Current Issue featuring articles on a wide range of subjects and approaches. We are delighted to present articles that all call for a reexamination of longheld beliefs about such ideas as the origin Photo‐bank and development of horseshoe arches (Gregory B. Kaplan), how and whether one can identify a Cistercian style of architecture in a particular area (Cynthia Marie Canejo), About the whether late medieval wills are truly reflective of the wishes of the decedent and how that Society affected pilgrimage and art in late medieval England (Matthew Champion), and whether an identification of a noble horseman in an earlysixteenth century painting can survive Submission scrutiny (Jan van Herwaarden). -

The German School Douglas House, Petersham Road, Petersham, Richmond, Surrey, TW10 7AH

School report The German School Douglas House, Petersham Road, Petersham, Richmond, Surrey, TW10 7AH Inspection dates 17–19 June 2014 Overall effectiveness Outstanding 1 Achievement of pupils Outstanding 1 Quality of teaching Outstanding 1 Behaviour and safety of pupils Outstanding 1 Leadership and management Outstanding 1 Summary of key findings This is an outstanding school Pupils achieve exceptionally high standards in Teachers are well qualified and experienced. most subjects throughout the school as a Their subject knowledge is very strong and result of outstanding teaching, an outstanding promotes a very high level of intellectual curriculum and excellent pastoral care. development in pupils. This, coupled with very All pupils, including those who have special high expectations of what pupils can achieve, educational needs, make good progress and enables pupils to make rapid and sustained most make outstanding progress in relation to progress. their starting points. Pupils’ behaviour and attitudes to learning are Bilingual education is very strong from outstanding. Pupils’ excellent personal Kindergarten onwards and pupils develop development is supported by a broad, excellent speaking, reading and writing skills balanced and extremely rich curriculum that in both German and English. They also attain helps them to become well-rounded high standards in mathematics. individuals. The work to keep pupils safe and Pupils have achieved exceptionally well in the promote their well-being is outstanding and Abitur (German Baccalaureate) in the last few pupils feel exceptionally well cared for. years. They have performed the highest in The leaders and managers at all levels, and languages and science. The first International the teaching staff have worked hard to Baccalaureate (IB) results show that pupils maintain the school’s excellent academic have made a good start in achieving a dual standards. -

The Programme AUGUST - SEPTEMBER 2017 2 About Us

german-ymca.org.uk Bring & Buy Trip to Eastbourne Peter’s Music Live Voices in Harmony The Lion King Au Pair Welcome Day Faith Talk: Reformation 5 The Programme AUGUST - SEPTEMBER 2017 2 About Us What is the German YMCA in London? We welcome people of different Christian traditions, those of other faiths Founded in 1860, the Association is and those of none. one of the oldest YMCAs in London and has been part of the English YMCA Although, because of our Association’s movement since that time. We are also heritage, the name contains “German”, one of the largest charities with German “Young” and “Men”, we welcome roots operating in England and anyone of any age and support the German-speaking nationality, male and and local community in a female. Our doors are variety of ways, from organised open to all, members events and programmes, and non-members alike. assistance to individuals in What other services do crisis situations, to material we offer? and practical support for other organisations. Through our Youth Secretaries and the On the following pages you Programme Secretary will find details of our regular (who is also the programmes and events: our Association’s Chaplain) Parent-Toddler group, the au we aim to give advice pair Tea Morning, the Anglo- to individuals, to those German Circle, Schubertiade in crisis situations and Concerts, trips and visits, and those just in need of much more. general advice. These Our home has been in the could be long-term Lancaster Gate, Bayswater area residents of London north of Hyde Park in central in need of ongoing London since 1959. -

Renaissance Art in Northern Europe

Professor Hollander Fall 2007 AH107 T, Th 2;20-3:45 AH107 HONORS OPTION STATEMENT Martha Hollander AH107, Northern Renaissance Art, covers visual culture—manuscript and panel painting, sculpture, tapestries, and printmaking,–– in fifteenth-and sixteenth-century Netherlands, Northern France, and Germany. Within a roughly chronological framework, the material is organized according to nationality and, to some extent, thematically, The four essays focus on areas of inquiry that occur at specific moments in the course. (Each essay is due the week during or after the relevant material is covered in class.) The attached reading list, which supplements the regular reading for the course, is designed as a resource of these essays. Two essays (2 and 3) are concerned with important texts of art theory as well as secondary scholarly texts which involve reading the texts and using artworks of the student’s choosing as illustrative examples. The other two essays (1 and 4) require in- depth analysis of specific assigned artworks, guiding the student to place the works in their artistic and social context. Taken together, the four essays (comprising between 8-15 pages) supplement the regular work of the course by enhancing the essential objectives of the course. The student will have the opportunity to exercise skills in understanding and applying contemporary ideas about art; and in engaging with specific objects. Each essay grade will be 10% of the final grade. The weight of the grades for regular coursework will be adjusted accordingly. The student and I will meet during my office hour every other week for planning and discussion. -

2014 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2014 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 11 5 4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 20 5 3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 19 3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 3 <3 <3 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 4 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 20 6 5 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 21 <3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 27 13 13 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 10 4 4 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 14 8 8 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent 4 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 3 3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 7 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 20 6 6 10046 Didcot Sixth Form College OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained -

The European Dimension in Vocational Training. Experiences and Tasks of Vocational Training Policy in the Member States of the European Union

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 392 881 CE 070 826 AUTHOR Koch, Richard, Ed.; Reuling, Jochen, Ed. TITLE The European Dimension in Vocational Training. Experiences and Tasks of Vocational Training Policy in the Member States of the European Union. Congress Report. INSTITUTION Federal Inst. for Vocational Training, Bonn (Germany). REPORT NO ISBN-3-7639-0690-8 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 208p. AVAILABLE FROMW. Bertelsmann Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Postfach 100633, D-33506 Bielefeld, Germany (order no. 110.313, 24 deutschmarks). PUB TYPE Collected Works - Conference Proceedings (021) -- Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.) (120) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Continuing Education; Educational Research; Foreign Countries; *International Cooperation; *International Educational Exchange; Job Training; *Organizational Development; Postsecondary Education; Secondary Education; Second Language Instruction; *Vocational Education IDENTIFIERS *Europe ABSTRACT This volume contains presentqtions and workshop papers from the International Congress on "The European Dimension of Vocational Training--Experiences and Tasks" that provided those with responsibility for vocational training a forum for analyzing and discussing challenges that have emerged from European cooperation in vocational training. Two introductory speeches (Karl-Hans Laermann and Achilleas Mitsos) precede the workshop papers. Workshop A, "The Bottom-Up Approach to Europe," looks at the form and content of projects based primarily on the initiative of chambers, companies, schools, and -

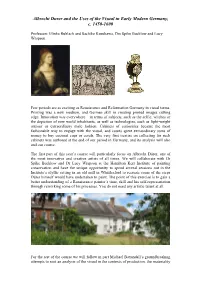

Uses of the Visual in Early Modern Germany, C

Albrecht Durer and the Uses of the Visual in Early Modern Germany, c. 1450-1600 Professors Ulinka Rublack and Sachiko Kusukawa, Drs Spike Bucklow and Lucy Wrapson Few periods are as exciting as Renaissance and Reformation Germany in visual terms. Printing was a new medium, and German skill in creating printed images cutting edge. Innovation was everywhere – in terms of subjects, such as the selfie, witches or the depiction of new world inhabitants, as well as technologies, such as light-weight armour or extraordinary male fashion. Cabinets of curiosities became the most fashionable way to engage with the visual, and courts spent extraordinary sums of money to buy coconut cups or corals. The very first treatise on collecting for such cabinets was authored at the end of our period in Germany, and its analysis will also end our course. The first part of this year’s course will particularly focus on Albrecht Dürer, one of the most innovative and creative artists of all times. We will collaborate with Dr Spike Bucklow and Dr Lucy Wrapson at the Hamilton Kerr Institute of painting conservation and have the unique opportunity to spend several sessions out in the Institute´s idyllic setting in an old mill in Whittlesford to recreate some of the steps Dürer himself would have undertaken to paint. The point of this exercise is to gain a better understanding of a Renaissance painter´s time, skill and his self-representation through reworking some of his processes. You do not need any artistic talent at all. For the rest of the course we will follow in part Michael Baxandall’s groundbreaking attempts to root an analysis of the visual in the contexts of production, the materiality of media and particular visual logic of the time, as well as the individual contribution of particular artists. -

Thomas Dacosta Kaufmann 146 Mercer Street Princeton, N.J

Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann 146 Mercer Street Princeton, N.J. 08540 Tel: 609-921-0154 ; cell : 609-865-8645 Fax: 609-258-0103 email: [email protected] CURRICULUM VITAE Education Collegiate School, New York, valedictorian Yale University, B.A., summa cum laude with exceptional distinction in History, the Arts and Letters, 1970 Yale University, M.A., with Honors, in History, 1970 Warburg Institute, University of London, M.Phil. Dissertation: Theories of Light in Renaissance Art and Science (Advisor: E. H. Gombrich), 1972 Harvard University, Ph. D., in Fine Arts Dissertation: “Variations on the Imperial Theme; Studies in Ceremonial Art, and Collecting in the Age of Maximilian II and Rudolf II” (Advisor: J. S. Ackerman), 1977 Employment Princeton University, Department of Art and Archaeology Frederick Marquand Professor of Art and Archaeology, 2007- Assistant Professor, 1977-1983; Associate Professor, 1983-1989; Professor, 1989-; Junior Advisor, 1978-1980; Departmental Representative (i.e., vice-chair for Undergraduate Studies, and Senior Advisor), 1983-1987, 1990-1991 Chairman, Committee for Renaissance Studies, 1990-93 University of San Marino, History Department, Professor, Lecture Cycle, 2010 Summer Art Theory Seminar, Globalization, School of Art Institute of Chicago, 2008, Professor Forschungsschwerpunkt Geschichte und Kultur Ostmitteleuropa (former Academy of Sciences, Berlin; Max-Planck-Gesellschaft), Visiting Professor, 1994 Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig, Stiftung Niedersachsen, Summer Course, Visiting Professor, 1994 University of Pennsylvania, Department of Art History Visiting Professor, 1980 Awards, Fellowships, and other Distinctions Elected Member, Latvian Academy of Sciences, 2020 Honorary Doctorate (Doctor historiae artrium, h.c.), Masaryk University, Brno, 2013 Wissenschaftlicher Gast, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, 2013 Nina Maria Gorissen Fellow in History (Berlin Prize Fellowship), American Academy in Berlin, 2013 Honorary Doctorate (Doctor phil. -

HUMANISM and the CLASSICAL TRADITION: NORTHERN RENAISSANCE: (Albrecht Dürer, Lucas Cranach, and Hans Holbein) NORTHERN RENAISSANCE: Durer, Cranach, and Holbein

HUMANISM and the CLASSICAL TRADITION: NORTHERN RENAISSANCE: (Albrecht Dürer, Lucas Cranach, and Hans Holbein) NORTHERN RENAISSANCE: Durer, Cranach, and Holbein Online Links: Albrecht Durer – Wikipedia Lucas Cranach the Elder – Wikipedia Hans Holbein the Younger – Wikipedia Durer's Adam and Eve – Smarthistory Durer's Self Portrait - Smarthistory Cranach's Law and Gospel - Smarthistory article Cranach's Adam and Eve - Smarthistory NORTHERN RENAISSANCE: Durer, Cranach, and Holbein Online Links: Cranach's Judith with Head of Holofernes – Smarthistory Holbein's Ambassadors – Smarthistory French Ambassadors - Learner.org A Global View Hans Holbein the Younger 1/3 – YouTube Hans Holbein the Younger 2/3 – YouTube Hans Holbein the Younger 3/3 - YouTube Holbein's Henry VIII – Smarthistory Holbein's Merchant Georg Gisze – Smarthistory Albrecht Durer - YouTube Part One of 6 Left: Silverpoint self-portrait of Albrecht Dürer at age 13 The German taste for linear quality in painting is especially striking in the work of Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528). He was first apprenticed to his father, who ran a goldsmith’s shop. Then he worked under a painter in Nuremberg, which was a center of humanism, and in 1494 and 1505 he traveled to Italy. He absorbed the revival of Classical form and copied Italian Renaissance paintings and sculptures, which he translated into a more rugged, linear northern style. He also drew the Italian landscape, studied Italian theories of proportion, and read Alberti. Like Piero della Francesca and Leonardo, Dürer wrote a book of advice to artists- the Four Books of Human Proportion. Left: Watercolor drawing of a young hare by Albrecht Dürer Like Leonardo da Vinci, Dürer was fascinated by the natural world.