I DECAPOD CRUSTACEANS from the CRETACEOUS of TEXAS In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Classification of Living and Fossil Genera of Decapod Crustaceans

RAFFLES BULLETIN OF ZOOLOGY 2009 Supplement No. 21: 1–109 Date of Publication: 15 Sep.2009 © National University of Singapore A CLASSIFICATION OF LIVING AND FOSSIL GENERA OF DECAPOD CRUSTACEANS Sammy De Grave1, N. Dean Pentcheff 2, Shane T. Ahyong3, Tin-Yam Chan4, Keith A. Crandall5, Peter C. Dworschak6, Darryl L. Felder7, Rodney M. Feldmann8, Charles H. J. M. Fransen9, Laura Y. D. Goulding1, Rafael Lemaitre10, Martyn E. Y. Low11, Joel W. Martin2, Peter K. L. Ng11, Carrie E. Schweitzer12, S. H. Tan11, Dale Tshudy13, Regina Wetzer2 1Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PW, United Kingdom [email protected] [email protected] 2Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90007 United States of America [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3Marine Biodiversity and Biosecurity, NIWA, Private Bag 14901, Kilbirnie Wellington, New Zealand [email protected] 4Institute of Marine Biology, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung 20224, Taiwan, Republic of China [email protected] 5Department of Biology and Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602 United States of America [email protected] 6Dritte Zoologische Abteilung, Naturhistorisches Museum, Wien, Austria [email protected] 7Department of Biology, University of Louisiana, Lafayette, LA 70504 United States of America [email protected] 8Department of Geology, Kent State University, Kent, OH 44242 United States of America [email protected] 9Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum, P. O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands [email protected] 10Invertebrate Zoology, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, 10th and Constitution Avenue, Washington, DC 20560 United States of America [email protected] 11Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 12Department of Geology, Kent State University Stark Campus, 6000 Frank Ave. -

Stratigraphy and Paleontology of Mid-Cretaceous Rocks in Minnesota and Contiguous Areas

Stratigraphy and Paleontology of Mid-Cretaceous Rocks in Minnesota and Contiguous Areas GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1253 Stratigraphy and Paleontology of Mid-Cretaceous Rocks in Minnesota and Contiguous Areas By WILLIAM A. COBBAN and E. A. MEREWETHER Molluscan Fossil Record from the Northeastern Part of the Upper Cretaceous Seaway, Western Interior By WILLIAM A. COBBAN Lower Upper Cretaceous Strata in Minnesota and Adjacent Areas-Time-Stratigraphic Correlations. and Structural Attitudes By E. A. M EREWETHER GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1 2 53 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 1983 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR JAMES G. WATT, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cobban, William Aubrey, 1916 Stratigraphy and paleontology of mid-Cretaceous rocks in Minnesota and contiguous areas. (Geological Survey Professional Paper 1253) Bibliography: 52 p. Supt. of Docs. no.: I 19.16 A. Molluscan fossil record from the northeastern part of the Upper Cretaceous seaway, Western Interior by William A. Cobban. B. Lower Upper Cretaceous strata in Minnesota and adjacent areas-time-stratigraphic correlations and structural attitudes by E. A. Merewether. I. Mollusks, Fossil-Middle West. 2. Geology, Stratigraphic-Cretaceous. 3. Geology-Middle West. 4. Paleontology-Cretaceous. 5. Paleontology-Middle West. I. Merewether, E. A. (Edward Allen), 1930. II. Title. III. Series. QE687.C6 551.7'7'09776 81--607803 AACR2 For sale by the Distribution Branch, U.S. -

Phylogeny, Diversity, and Ecology of the Ammonoid Superfamily Acanthoceratoidea Through the Cenomanian and Turonian

PHYLOGENY, DIVERSITY, AND ECOLOGY OF THE AMMONOID SUPERFAMILY ACANTHOCERATOIDEA THROUGH THE CENOMANIAN AND TURONIAN DAVID A.A. MERTZ A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August 2017 Committee: Margaret Yacobucci, Advisor Andrew Gregory Keith Mann © 2017 David Mertz All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Margaret Yacobucci Both increased extinction and decreased origination, caused by rising oceanic anoxia and decreased provincialism, respectively, have been proposed as the cause of the Cenomanian Turonian (C/T) extinction event for ammonoids. Conflicting evidence exists for whether diversity actually dropped across the C/T. This study used the ammonoid superfamily Acanthoceratoidea as a proxy for ammonoids as a whole, particularly focusing on genera found in the Western Interior Seaway (WIS) of North America, including Texas. Ultimately, this study set out to determine 1) whether standing diversity decreased across the C/T boundary in the WIS, 2) whether decreased speciation or increased extinction in ammonoids led to a drop in diversity in the C/T extinction event, 3) how ecology of acanthoceratoid genera changed in relation to the C/T extinction event, and 4) whether these ecological changes indicate rising anoxia as the cause of the extinction. In answering these questions, three phylogenetic analyses were run that recovered the families Acanthoceratidae, Collignoniceratidae, and Vascoceratidae. Pseudotissotiidae was not recovered at all, while Coilopoceratidae was recovered but reclassified as a subfamily of Vascoceratidae. Seven genera were reclassified into new families and one genus into a new subfamily. After calibrating the trees with stratigraphy, I was able to determine that standing diversity dropped modestly across the C/T boundary and the Early/Middle Turonian boundary. -

Phylogenetics of the Brachyuran Crabs (Crustacea: Decapoda): the Status of Podotremata Based on Small Subunit Nuclear Ribosomal RNA

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 45 (2007) 576–586 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Phylogenetics of the brachyuran crabs (Crustacea: Decapoda): The status of Podotremata based on small subunit nuclear ribosomal RNA Shane T. Ahyong a,*, Joelle C.Y. Lai b, Deirdre Sharkey c, Donald J. Colgan c, Peter K.L. Ng b a Biodiversity and Biosecurity, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, Private Bag 14901 Kilbirnie, Wellington, New Zealand b School of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, Kent Ridge, Singapore c Australian Museum, 6 College Street, Sydney, NSW 2010, Australia Received 26 January 2007; revised 13 March 2007; accepted 23 March 2007 Available online 13 April 2007 Abstract The true crabs, the Brachyura, are generally divided into two major groups: Eubrachyura or ‘advanced’ crabs, and Podotremata or ‘primitive’ crabs. The status of Podotremata is one of the most controversial issues in brachyuran systematics. The podotreme crabs, best recognised by the possession of gonopores on the coxae of the pereopods, have variously been regarded as mono-, para- or polyphyletic, or even as non-brachyuran. For the first time, the phylogenetic positions of the podotreme crabs were studied by cladistic analysis of small subunit nuclear ribosomal RNA sequences. Eight of 10 podotreme families were represented along with representatives of 17 eubr- achyuran families. Under both maximum parsimony and Bayesian Inference, Podotremata was found to be significantly paraphyletic, comprising three major clades: Dromiacea, Raninoida, and Cyclodorippoida. The most ‘basal’ is Dromiacea, followed by Raninoida and Cylodorippoida. Notably, Cyclodorippoida was identified as the sister group of the Eubrachyura. -

Crustacean Research 49: 237-262 (2020)

Crustacean Research 2020 Vol.49: 237–262 ©Carcinological Society of Japan. doi: 10.18353/crustacea.49.0_237 Description of a new genus for Cyrtorhina balabacensis Serène, 1971, with notes on the Cyrtorhininae (Decapoda, Brachyura, Raninidae) Peter K. L. Ng, Danièle Guinot Abstract.̶ The raninid genus Cyrtorhina Monod, 1956, is revised and restricted to Cyrtorhina granulosa Monod, 1956, from West Africa. A new genus, Flaberhina, is established for C. balabacensis Serène, 1971 from the Philippines and New Caledonia. Despite their superficial similarities, the two genera can easily be separated by the structures of the carapace, eye, antenna, pterygostome, thoracic sternum, pleon and penis. The taxonomy of the subfamily Cyrtorhininae Guinot & Ng, 2020, which con- tains both fossil and extant taxa, is also reviewed. LSID urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:D9C27598-A52F-4207-8C22-CDDF9E8E8FFD Key words: Raninoidea, Cyrtorhina, Flaberhina, new genus, Cyrtorhininae, systematics, review ■ Introduction until the present study. Serène & Umali (1972: 49) subsequently redescribed and figured the The raninid genus Cyrtorhina Monod, 1956, species and type specimen in greater detail. was established for one new species, Cyrtorhina balabacensis was known only from C. granulosa Monod, 1956. The holotype was the single type female of Serène (1971). a dry specimen in the Muséum national Between 2001 and 2002, however, the authors d'Histoire naturelle (MNHN), Paris, labelled as obtained three specimens of C. balabacensis “Cyrtorhina granulosa nov. sp. (A. Milne Ed- from fishermen in Balicasag Island in the cen- wards in sched.)” but the name was never pub- tral Philippines, all collected by tangle nets. lished by A. Milne Edwards. -

Characteristic Marine Molluscan Fossils from the Dakota Sandstone and Intertongued Mancos Shale, West-Central New Mexico

Characteristic Marine Molluscan Fossils From the Dakota Sandstone and Intertongued Mancos Shale, West-Central New Mexico GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1009 Characteristic Marine Molluscan Fossils From the Dakota Sandstone and Intertongued Mancos Shale, West-Central New Mexico By WILLIAM A. COBBAN GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1009 Brief descriptions, illustrations, and stratigraphic sequence of the more common fossils at the base of the Cretaceous System UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1977 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cobban, William Aubrey, 1916- Characteristic marine molluscan fossils from the Dakota sandstone and intertongued Mancos shale, West- central New Mexico. (Geological Survey professional paper ; 1009) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Lamellibranchiata, Fossil. 2. Gastropoda, Fossil. 3. Ammonoidea. 4. Paleontology Cretaceous. 5. Paleontol ogy New Mexico. I. Title: Characteristic marine molluscan fossils from the Dakota sandstone ***!!. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Professional paper ; 1009. QE811.G6 564'.09789'8 76-26956 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Stock Number 024-001-03003-9 CONTENTS Page Abstract ________________________________________--__- 1 Introduction ________________________________________ Acknowledgments _____________________________ Stratigraphic summary _________________________ -

Taxonomy and Stratigraphic Distribution of the Ammonite Schloenbachia Neumayr, 1875 from the Bohemian Cretaceous Basin

FOSSIL IMPRINT • vol. 75 • 2019 • no. 1 • pp. 64–69 (formerly ACTA MUSEI NATIONALIS PRAGAE, Series B – Historia Naturalis) TAXONOMY AND STRATIGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION OF THE AMMONITE SCHLOENBACHIA NEUMAYR, 1875 FROM THE BOHEMIAN CRETACEOUS BASIN MARTIN KOŠŤÁK1,*, JAN SKLENÁŘ2, MARTIN MAZUCH1, STANISLAV ČECH3 1 Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Albertov 6, 128 43 Praha 2, the Czech Republic; e-mail: [email protected], martin.mazuch@ natur.cuni.cz. 2 Department of Palaeontology, National Museum, Václavské náměstí 68, 110 00 Praha 1, the Czech Republic; e-mail: [email protected]. 3 Czech Geological Survey, Klárov 3/131, 118 21 Praha 1, the Czech Republic; e-mail: [email protected]. * corresponding author Košťák, M., Sklenář, J., Mazuch, M., Čech, S. (2019): Taxonomy and stratigraphic distribution of the ammonite Schloenbachia NEUMAYR, 1875 from the Bohemian Cretaceous Basin – Fossil Imprint, 75(1): 64–69, Praha. ISSN 2533-4050 (print), ISSN 2533-4069 (on-line). Abstract: Only two specimens of the ammonite genus Schloenbachia have hitherto been recorded from the Bohemian Cretaceous Basin (BCB). While the first specimen was originally described by Dr. J. Soukup in the 1970s, the other one was discovered in an older collection of the Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague in 2018. Recently, both specimens were systematically investigated and interpreted as Schloenbachia lymensis, a new ammonite species for the BCB. The stratigraphic distribution of S. lymensis as well as the palaeobiogeography of this taxon are discussed in this paper. Key words: Upper Cenomanian, Bohemian Cretaceous Basin, ammonites, Schloenbachia lymensis Received: March 1, 2019 | Accepted: May 29, 2019 | Issued: August xx, 2019 Introduction group is still under discussion (Wright and Kennedy 2015, Machalski 2018, and others). -

Shrimps, Lobsters, and Crabs of the Atlantic Coast of the Eastern United States, Maine to Florida

SHRIMPS, LOBSTERS, AND CRABS OF THE ATLANTIC COAST OF THE EASTERN UNITED STATES, MAINE TO FLORIDA AUSTIN B.WILLIAMS SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS Washington, D.C. 1984 © 1984 Smithsonian Institution. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Williams, Austin B. Shrimps, lobsters, and crabs of the Atlantic coast of the Eastern United States, Maine to Florida. Rev. ed. of: Marine decapod crustaceans of the Carolinas. 1965. Bibliography: p. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: SI 18:2:SL8 1. Decapoda (Crustacea)—Atlantic Coast (U.S.) 2. Crustacea—Atlantic Coast (U.S.) I. Title. QL444.M33W54 1984 595.3'840974 83-600095 ISBN 0-87474-960-3 Editor: Donald C. Fisher Contents Introduction 1 History 1 Classification 2 Zoogeographic Considerations 3 Species Accounts 5 Materials Studied 8 Measurements 8 Glossary 8 Systematic and Ecological Discussion 12 Order Decapoda , 12 Key to Suborders, Infraorders, Sections, Superfamilies and Families 13 Suborder Dendrobranchiata 17 Infraorder Penaeidea 17 Superfamily Penaeoidea 17 Family Solenoceridae 17 Genus Mesopenaeiis 18 Solenocera 19 Family Penaeidae 22 Genus Penaeus 22 Metapenaeopsis 36 Parapenaeus 37 Trachypenaeus 38 Xiphopenaeus 41 Family Sicyoniidae 42 Genus Sicyonia 43 Superfamily Sergestoidea 50 Family Sergestidae 50 Genus Acetes 50 Family Luciferidae 52 Genus Lucifer 52 Suborder Pleocyemata 54 Infraorder Stenopodidea 54 Family Stenopodidae 54 Genus Stenopus 54 Infraorder Caridea 57 Superfamily Pasiphaeoidea 57 Family Pasiphaeidae 57 Genus -

Decapod Crustacea : Raninidae

CAMPAGNES MUSORSTOM. I & II. PHILIPPINES, TOME 2 — RÉSULTATS DES CAMPAGNES MUSORSTOM. I & II. PHILIPPINES, 6 Decapod Crustacea : Raninidae Gary D. GOEKE * ABSTRACT Nine species of frog crabs of the family Raninidae were collected during the 1976 and 1980 MUSORSTOM cruises to the Philippines and the 1980 CORINDON II cruise in Makassar Strait. A proposed new genus, Lysirude (containing 3 species) is described and separated from the closely related genus Lyreidus. Five species (Raninoides hendersoni, R. personatus, Lyreidus tridentatus, L. stenops and Lysirude channeri) are represented by numerous specimens with far fewer specimens of Cosmonotus grayi, Notopoides latus, Lyreidus brevifrons and Lysirude grif- fini sp. nov. present. RÉSUMÉ Neuf espèces de Crabes de la famille des Raninidae ont été récoltées au cours des campagnes MUSORSTOM 1976 et 1980 aux Philippines et de la campagne CORINDON II dans le détroit de Macassar. Un nouveau genre Lysirude (avec trois espèces) est décrit et séparé du genre très proche Lyreidus. Cinq espèces (Raninoides hender soni, R. personatus, Lyreidus tridentatus, L. stenops et Lysirude channeri) sont représentées par de nombreux spé cimens, tandis que d'autres (Cosmonotus grayi, Notopoides latus, Lyreidus brevifrons et Lysirude griffini sp. nov.) ne comprennent qu'un nombre moins élevé d'échantillons. The Raninidae of the Philippines are a diverse group well represented in the MUSORSTOM col lections. Species of this fossorial group collected in the Philippines were most recently detailed by SERENE and UMALI (1972) and SERENE and VADON (1981). This contribution presents a systematic review of the Philippine species with an updated key to the recognized species of frog crabs known from the region. -

Novitates PUBLISHED by the AMERICAN MUSEUM of NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST at 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, N.Y

AMERICAN MUSEUM Novitates PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, N.Y. 10024 Number 3161, 18 pp., 17 figures, 3 tables April 10, 1996 New Records of Acanthoceratid Ammonoids from the Upper Cenomanian of South Dakota W. J. KENNEDY,1 W. A. COBBAN,2 AND N. H. LANDMAN3 ABSTRACT The upper Cenomanian Metoicoceras mos- thoceras proteus vascoceratoides Wright and Ken- byense zone of the Belle Fourche area in Butte nedy, 1987, and Yezoites n. sp. These species are County, South Dakota, has yielded a number of similar to those reported from the M. mosbyense ammonoid species, some of them new, that show zone in southwestern New Mexico and suggest a both U.S. Westem Interior and northwest Euro- possible influx offorms from the south, migrating pean affinities, including Calycoceras (Calycocer- via the Gulf Coast region, well before the better- as) boreale n. sp., C. (C.) sp., C. (C.) cf. dromense known interchange of Western Interior and more (Thomel, 1972), Calycoceras (Gentoniceras) sp., cosmopolitan taxa in the succeeding Sciponoceras Hamites cimarronensis (Kauffman and Powell, gracile zone. 1977), Neocardioceras transiens n. sp., Protacan- INTRODUCTION The bulk of the ammonoid species known demic species (fig. 1). This is in marked con- from the upper Cenomanian Metoicoceras trast to the predominantly cosmopolitan as- mosbyense zone in the northern part of the semblage known in the succeeding Scipono- Western Interior ofthe United States are en- ceras gracile zone (for a description of this I Curator of the Geological Collections, University Museum, Parks Road, Oxford, OXI 3PW, United Kingdom. -

Systematic Evaluation of Raninid Cuticle Microstructure

Bulletin of the Mizunami Fossil Museum, no. 35 (2009), p. 15–41, 13 figs., 2 tables. 5 © 2009, Mizunami Fossil Museum Systematic evaluation of raninid cuticle microstructure David A. Waugh1, Rodney M. Feldmann1, and Carrie E. Schweitzer2 1Department of Geology, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 44242 USA<[email protected]><[email protected]> 2Department of Geology, Kent State University Stark Campus, 6000 Frank Ave. NW, North Canton Ohio 44720 USA<[email protected]> Abstract Studies of decapod cuticle microstructure in both the paleontologic and neontologic literature generally focus on understanding cuticular construction and recognizing these features in fossil material. We examine the cuticle of 57 species in 26 genera within the Raninoidea. Within each genus cuticle microstructure of raninids is generally similar, but in successively higher taxonomic groups, greater variance is seen within and between groups. The subfamily Lyreidinae contains microstructures limited to pits and upright nodes. The Paleocorystinae contains species with predominantly upright nodes and cuticle that generally differs from the other subfamilies. The remaining subfamilies, including the Ranininae, Raninoidinae, Cyrtorhininae, and Notopodinae, are generally similar in their cuticle microstructure; they exhibit inclined nodes, and various combinations of pits, setal pits, depressions, and perforations. The Symethidae contains fungiform nodes, similar to those seen in Cretacoranina, a genus within the Paleocorystinae. Traditional taxonomic characters clearly separate the subfamilies of the Raninidae as well as separating the Raninidae from the Symethidae. Similar cuticle microstructures may appear in different subfamilies. Based upon cuticle microstructure alone, the Raninidae can be divided into three, morphotypes; the Paleocorystinae with upright and fungiform nodes, the Lyreidinae with pits and upright nodes, and the Ranininae, Raninoidinae, Cyrtorhininae, and Notopodinae with inclined nodes. -

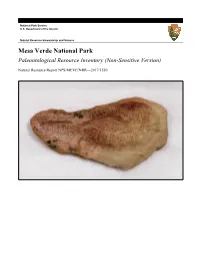

Mesa Verde National Park Paleontological Resource Inventory (Non-Sensitive Version)

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Mesa Verde National Park Paleontological Resource Inventory (Non-Sensitive Version) Natural Resource Report NPS/MEVE/NRR—2017/1550 ON THE COVER An undescribed chimaera (ratfish) egg capsule of the ichnogenus Chimaerotheca found in the Cliff House Sandstone of Mesa Verde National Park during the work that led to the production of this report. Photograph by: G. William M. Harrison/NPS Photo (Geoscientists-in-the-Parks Intern) Mesa Verde National Park Paleontological Resources Inventory (Non-Sensitive Version) Natural Resource Report NPS/MEVE/NRR—2017/1550 G. William M. Harrison,1 Justin S. Tweet,2 Vincent L. Santucci,3 and George L. San Miguel4 1National Park Service Geoscientists-in-the-Park Program 2788 Ault Park Avenue Cincinnati, Ohio 45208 2National Park Service 9149 79th St. S. Cottage Grove, Minnesota 55016 3National Park Service Geologic Resources Division 1849 “C” Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20240 4National Park Service Mesa Verde National Park PO Box 8 Mesa Verde CO 81330 November 2017 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service.