How Colombia Can Plan for a Future Without Coal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Water Rights-Based Legal Mobilization of the Wayúu Against the Cercado Dam: an Effective Avenue for Court-Centered Lawfare from Below?*

The Water Rights-Based Legal Mobilization of the Wayúu against the Cercado Dam: An Effective Avenue for Court-Centered Lawfare from Below?* Sergi Vidal Parra** University of Deusto, País Vasco https://doi.org/10.7440/antipoda34.2019.03 How to cite this article: Vidal Parra, Sergi. 2019. “The Water Rights-Based Legal Mobilization of the Wayúu against the Cercado Dam: An Effective Avenue for Court-Centered Lawfare from Below?” Antípoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología 34: 45-68. https://doi.org/10.7440/ antipoda34.2019.03 Reception date: January 29, 2018; Acceptance date: August 28, 2018; Modification date: September 28, 2018. Abstract: Objective/Context: In recent years, decreasing water availability, accessibility, and quality in the Upper and Middle Guajira has led to the death of thousands of Wayúu people. This has been caused by precipitation 45 deficit and droughts and hydro-colonization by mining and hydropower projects. This study assesses the effectiveness of the Wayúu’s legal mobili- zation to redress the widespread violation of their fundamental rights on the basis of the enforceability and justiciability of the human right to water. Methodology: The study assesses the effects of the Wayúu’s legal mobiliza- tion by following the methodological approach proposed by Siri Gloppen, * This paper is result of two field studies conducted in the framework of my doctoral studies: firstly, PARALELOS a six-month research stay at the Research and Development Institute in Water Supply, Environmental Sanitation and Water Resources Conservation of the Universidad del Valle, Cali (2016-2017); secondly, the participation in the summer courses on “Effects of Lawfare: Courts and Law as Battlegrounds for Social Change” at the Centre on Law and Social Transformation (Bergen 2017). -

Quaternary Activity of the Bucaramanga Fault in the Depart- Ments of Santander and Cesar

Volume 4 Quaternary Chapter 13 Neogene https://doi.org/10.32685/pub.esp.38.2019.13 Quaternary Activity of the Bucaramanga Fault Published online 27 November 2020 in the Departments of Santander and Cesar Paleogene Hans DIEDERIX1* , Olga Patricia BOHÓRQUEZ2 , Héctor MORA–PÁEZ3 , 4 5 6 Juan Ramón PELÁEZ , Leonardo CARDONA , Yuli CORCHUELO , 1 [email protected] 7 8 Jaír RAMÍREZ , and Fredy DÍAZ–MILA Consultant geologist Servicio Geológico Colombiano Dirección de Geoamenazas Abstract The 350 km long Bucaramanga Fault is the southern and most prominent Grupo de Trabajo Investigaciones Geodésicas Cretaceous Espaciales (GeoRED) segment of the 550 km long Santa Marta–Bucaramanga Fault that is a NNW striking left Dirección de Geociencias Básicas Grupo de Trabajo Tectónica lateral strike–slip fault system. It is the most visible tectonic feature north of latitude Paul Krugerstraat 9, 1521 EH Wormerveer, 6.5° N in the northern Andes of Colombia and constitutes the western boundary of the The Netherlands 2 [email protected] Maracaibo Tectonic Block or microplate, the southeastern boundary of the block being Servicio Geológico Colombiano Jurassic Dirección de Geoamenazas the right lateral strike–slip Boconó Fault in Venezuela. The Bucaramanga Fault has Grupo de Trabajo Investigaciones Geodésicas Espaciales (GeoRED) been subjected in recent years to neotectonic, paleoseismologic, and paleomagnetic Diagonal 53 n.° 34–53 studies that have quantitatively confirmed the Quaternary activity of the fault, with Bogotá, Colombia 3 [email protected] eight seismic events during the Holocene that have yielded a slip rate in the order of Servicio Geológico Colombiano Triassic Dirección de Geoamenazas 2.5 mm/y, whereas a paleomagnetic study in sediments of the Bucaramanga alluvial Grupo de Trabajo Investigaciones Geodésicas fan have yielded a similar slip rate of 3 mm/y. -

Centros De Atención Ciudadana Unidades De Reacción Inmediata

Centros de Atención Ciudadana Unidades de Reacción Inmediata- URI Seccional Municipio / Dirección Teléfono Localidad Armenia Armenia Palacio de Justicia P - 1 57(6) 744 3672 Barranquilla Barranquilla Cll. 41 No. 41 - 69 57(5) 344 0030 Bogotá Ciudad Bolívar Cll. 54 Sur No. 16 - 03 57(1) 760 3644 Bogotá Usaquén Cr. 32 No. 13 A 20 Bogotá Paloquemao Av. 19 No. 29 - 75 P - 1 57(1) 297 1177 Bogotá Engativá Cr. 78 A No. 77 A - 62 57(1) 430 3318 Bogotá Kennedy Cr. 72 J No. 36 - 56 / 58 57(1) 299 3515 Sur Bucaramanga Bucaramanga Cr. 19 No. 24 - 61 P - 1 57(7) 652 2222 Ext. 2103 - 2114 -2110 Bucaramanga Barrancabermeja Palacio de Justicia 57(7) 621 3652 Buga Buga Cr. 9 Bis No. 17 - 71 57(2) 237 3064 Buga Buenaventura Cll. 3 No. 3 A - 01 57(2) 240 1541 Buga Cartago Cr. 5 No. 12 A - 23 57(2) 214 6061 - 57(2) 213 2201 Buga Tuluá Cll. 23 No. 26 - 31 57(2) 225 8561 Cali Cali Cll. 11 Cr. 60 Santa Anita 57(2) 312 5327 Cali Palmira Cr. 33 No. 30 - 01 57(2) 272 8253 - 57(2)275 6980 Cali Yumbo Cll. 4 No. 2 -24 57(2)669 5943 - 57(2)669 5945 Cali Siloé Cr. 52 Cll. 2 Estación Lido 57(2)513 5368 Cali Aguablanca Cr. 26 M Cll. 73 Los 57(2)422 9653 Mangos Cartagena Cartagena Crespo Cll. 66 No. 4 - 86 57(5) 656 2751 P - 1 Cúcuta Cúcuta Av. Gran Colombia 2 E - 57(7) 5775058 91 Cundinamarca Girardot Caja Agraria P - 3 57(1) 835 2375 Cundinamarca Fusagasugá Casa del Molino Puente 57(1) 867 2180 del Aguila Cundinamarca Soacha Cr. -

UNHCR Colombia Receives the Support of Private Donors And

NOVEMBER 2020 COLOMBIA FACTSHEET For more than two decades, UNHCR has worked closely with national and local authorities and civil society in Colombia to mobilize protection and advance solutions for people who have been forcibly displaced. UNHCR’s initial focus on internal displacement has expanded in the last few years to include Venezuelans and Colombians coming from Venezuela. Within an interagency platform, UNHCR supports efforts by the Government of Colombia to manage large-scale mixed movements with a protection orientation in the current COVID-19 pandemic and is equally active in preventing statelessness. In Maicao, La Guajira department, UNHCR provides shelter to Venezuela refugees and migrants at the Integrated Assistance Centre ©UNHCR/N. Rosso. CONTEXT A peace agreement was signed by the Government of Colombia and the FARC-EP in 2016, signaling a potential end to Colombia’s 50-year armed conflict. Armed groups nevertheless remain active in parts of the country, committing violence and human rights violations. Communities are uprooted and, in the other extreme, confined or forced to comply with mobility restrictions. The National Registry of Victims (RUV in Spanish) registered 54,867 displacements in the first eleven months of 2020. Meanwhile, confinements in the departments of Norte de Santander, Chocó, Nariño, Arauca, Antioquia, Cauca and Valle del Cauca affected 61,450 people in 2020, as per UNHCR reports. The main protection risks generated by the persistent presence of armed groups and illicit economies include forced recruitment of children by armed groups and gender- based violence – the latter affecting in particular girls, women and LGBTI persons. Some 2,532 cases of GBV against Venezuelan women and girls were registered by the Ministry of Health between 1 January and September 2020, a 41.5% increase compared to the same period in 2019. -

A Land Title Is Not Enough

A LAND TITLE IS NOT ENOUGH ENsuRINg sustAINAblE lANd REstItutIoN IN ColoMbIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: AMR 23/031/2014 English Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo : A plot of land in El Carpintero, Cabuyaro Municipality, Meta Department. Most of the peasant farmers from El Carpintero were forced to flee their homes following a spate of killings and forced disappearances of community members carried out by paramilitary groups in the late 1990s. -

Costos De Referencia Por Tonelada Para Un Tractocamión

Costos de referencia por tonelada para un tractocamión A. Costo de traslado por tonelada: costo de movilizar el vehículo en un origen destino (excluye el costo de las horas de espera, carga y descarga): Destino Origen ARMENIA BARRANQUILLA BOGOTA BUCARAMANGA BUENAVENTURA CALI CARTAGENA CARTAGO (VALLE) CUCUTA DUITAMA FLORENCIA IBAGUE IPIALES-NARIÑO MANIZALES MEDELLÍN MOCOA MONTERIA NEIVA PASTO PEREIRA POPAYAN RIOHACHA SANTA MARTA SINCELEJO SOGAMOSO-BOYACA TUMACO VALLEDUPAR VILLAVICENCIO YOPAL ARMENIA 0 147,088.02 51,435.21 90,867.55 37,188.58 25,244.58 141,831.01 6,226.27 129,564.08 91,604.83 81,360.80 15,977.40 110,146.80 16,158.00 53,478.20 95,267.72 106,598.44 45,584.61 93,023.40 6,714.30 48,372.69 188,134.49 146,487.17 116,749.99 84,415.54 140,460.66 149,713.92 77,904.60 110,856.13 BARRANQUILLA 147,088.02 0 137,272.09 83,390.47 178,630.52 166,668.91 14,070.86 144,632.31 96,450.85 143,677.71 224,939.36 142,337.02 249,811.24 129,831.66 101,648.62 238,876.87 50,133.48 164,545.22 234,243.72 134,418.54 187,573.53 42,586.17 11,910.01 32,809.81 139,761.06 277,784.90 46,770.83 164,488.22 168,392.50 BOGOTA 51,435.21 138,233.82 0 55,255.22 89,187.92 77,043.29 135,233.75 54,842.99 92,171.94 35,006.67 84,220.29 31,395.20 160,911.25 49,692.97 62,323.89 98,130.08 118,254.94 47,110.43 145,233.02 55,359.04 99,123.05 174,708.22 130,892.80 128,776.44 30,340.24 194,100.54 136,279.15 21,374.71 60,821.25 BUCARAMANGA 90,867.55 83,390.47 55,255.22 0 131,675.22 117,840.86 88,596.13 91,558.30 34,641.23 58,901.60 148,179.89 73,840.73 204,654.47 79,268.42 69,881.52 -

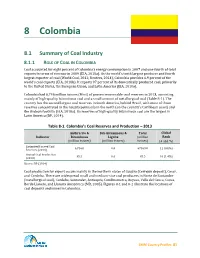

Chapter 8: Colombia

8 Colombia 8.1 Summary of Coal Industry 8.1.1 ROLE OF COAL IN COLOMBIA Coal accounted for eight percent of Colombia’s energy consumption in 2007 and one-fourth of total exports in terms of revenue in 2009 (EIA, 2010a). As the world’s tenth largest producer and fourth largest exporter of coal (World Coal, 2012; Reuters, 2014), Colombia provides 6.9 percent of the world’s coal exports (EIA, 2010b). It exports 97 percent of its domestically produced coal, primarily to the United States, the European Union, and Latin America (EIA, 2010a). Colombia had 6,746 million tonnes (Mmt) of proven recoverable coal reserves in 2013, consisting mainly of high-quality bituminous coal and a small amount of metallurgical coal (Table 8-1). The country has the second largest coal reserves in South America, behind Brazil, with most of those reserves concentrated in the Guajira peninsula in the north (on the country’s Caribbean coast) and the Andean foothills (EIA, 2010a). Its reserves of high-quality bituminous coal are the largest in Latin America (BP, 2014). Table 8-1. Colombia’s Coal Reserves and Production – 2013 Anthracite & Sub-bituminous & Total Global Indicator Bituminous Lignite (million Rank (million tonnes) (million tonnes) tonnes) (# and %) Estimated Proved Coal 6,746.0 0.0 67469.0 11 (0.8%) Reserves (2013) Annual Coal Production 85.5 0.0 85.5 10 (1.4%) (2013) Source: BP (2014) Coal production for export occurs mainly in the northern states of Guajira (Cerrejón deposit), Cesar, and Cordoba. There are widespread small and medium-size coal producers in Norte de Santander (metallurgical coal), Cordoba, Santander, Antioquia, Cundinamarca, Boyaca, Valle del Cauca, Cauca, Borde Llanero, and Llanura Amazónica (MB, 2005). -

Geological Occurrence of the Ecce Homo Hill´S Cave, Chimichagua (Cesar), Colombia: an Alternative for Socio-Economic Development Based on Geotourism

International Journal of Hydrology Review Article Open Access Geological occurrence of the ecce homo hill´s cave, chimichagua (cesar), Colombia: an alternative for socio-economic development based on geotourism Abstract Volume 2 Issue 5 - 2018 This work presents the results of the speleological study developed in the Ecce Homo Ciro Raúl Sánchez-Botello,1 Gabriel Jiménez- Cerro Cave located in the southwest of the central subregion of the Cesar department, Velandia,1 Carlos Alberto Ríos-Reyes,1 Dino in the Colombian Caribbean region, associated with carbonated rocks of the Aguas 2 Blancas Formation belonging to the Cogollo Group, which have suffered Chemical Carmelo Manco-Jaraba, Elías Ernesto Rojas- 2 and mechanical dissolution generating endocárstico and exocárstico environments. In Martínez, Oscar Mauricio Castellanos- the cavern were found different types of pavillian, paving and zenith speleothems of Alarcón3 different sizes in the galleries, being this the tourist attraction of such cavity, such as 1Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia columns, moonmilk, stalactites, castings, sawtooth, gours and flags. Lithologically, 2Fundación Universitaria del Área Andina, Valledupar, Colombia this geological unit is constituted by gray, biomicritic and dismicríticas limestones 3Programa de Geología, Universidad de Pamplona, Pamplona, with high fossiliferous content, intercalations of shales, recrystallized sediments with Colombia calcium carbonate, pellets and shells recrystallized with calcium carbonate. The Ecce Carlos Alberto Ríos-Reyes, Universidad Homo Cerro Cave can be catalogued as a punctual Geosite with geomorphological Correspondence: Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia, interest, taking into account the large number and variety of speleothems presented as Email [email protected] well as its excellent state of preservation. -

IOM Colombia Projects: Post-Emergency Migration Management

IOM Colombia Projects: Post-Emergency Migration Management Protection of Patrimonial Assets of Colombia’s Internally Displaced Population Donors: Social Solidarity Network, World Bank, Swedish International Development Agency, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and Government of Colombia – Department of Norte de Santander • Personnel from Public Notary offices were trained in “land protection routes”, through different workshops in the cities of Barranquilla, Medellín, Armenia and Bogotá. • Staff from Offices for Registry of Public Instruments in Bogotá and Medellin were provided with training in land protection mechanisms. • The monitoring and evaluation system for budget follow-up was updated. • Colombian Congress recently approved Law 1152/2007. This law changed land regulations regarding the project, therefore having a direct impact on project implementation. Inter-institutional Cooperation between IOM and the Social Solidarity Network Donor: Social Solidarity Network • The sub-project "Integral support for socioeconomic establishment of the Indian communities Alto Andagueda, Department of Choco” was succesfully completed. Integrated Humanitarian Assistance Support to Internally Displaced Persons and Other Vulnerable Groups in Colombia (Programme to Assist IDPs and Vulnerable Groups) Donor: USAID through the Pan-American Development Foundation (PADF) • A total of seven projects were approved in the areas of income generation, institutional strengthening, emergencies, housing, investigation and studies and education. • The -

8:00 Am - 5:00 Pm CC Nuestro Urabá Km 1 Vía APARTADÓ SAO APARTADO 8:00 A.M

OFICINAS HABILITADAS HORARIO ASESORES CIUDAD NOMBRE HORARIO OFICINA COMERCIALES OLIMPICA L-V: 8:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. ARMENIA ARMENIA y 2:00 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. N/A L-V: 8:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. BARRANQUILLA PLAZA DEL PARQUE y 2:00 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. N/A S: 9:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. L-V: 8:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. BARRANQUILLA PRINCIPAL CRA 55 S: 9:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. N/A L-V: 8:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. BARRANQUILLA SAO 53 y 2:00 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. L-S: 8:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. S: 8:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. L-V: 8:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. BARRANQUILLA SAO 93 y 2:00 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. L-S: 8:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. S: 8:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. L-V: 8:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. BARRANQUILLA ALTO PRADO y 2:00 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. L-S: 8:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. S: 8:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. L-V: 8:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. BARRANQUILLA SAO HIPODROMO y 2:00 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. L-S: 8:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. S: 8:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. L-V: 8:00 a.m. -

Doing Business in Colombia 2017 Overview

OVERVIEW 1 Doing Business in Colombia 2017 Overview Comparing Business Regulation for Domestic Firms in 32 Colombian Cities with 189 Other Economies 2 DOING BUSINESS IN COLOMBIA 2017 © 2017 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 19 18 17 16 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. All maps in this report were produced by the Cartography Unit of the World Bank Group. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: World Bank. -

Bogotá, Colombia – Quarterly Report January – March 2008

PROGRAMA CIMIENTOS – BOGOTÁ, COLOMBIA – QUARTERLY REPORT JANUARY – MARCH 2008 APRIL 30, 2008 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Management Systems International. PROGRAMA CIMIENTOS – BOGOTÁ, COLOMBIA – QUARTERLY REPORT JANUARY – MARCH 2008 Contracted under Task Order Contract: DFD-I-03-05-00221-00 Colombia Regional Governance & Consolidation Program CIMIENTOS DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 II. ACTIVITIES BY COMPONENT AT THE NATIONAL LEVEL .............................. 1 A. Component 1. Improving Citizen Security and Effective State Presence in Health and Education ................................................................................................. 1 B. Component 2: Building governance capacity in targeted regions ............................. 6 C. Cross-cutting component: Civil Society ................................................................. 11 III. ACTIVITIES AND CONTEXT AT THE REGIONAL LEVEL ............................... 14 A. National Level .......................................................................................................... 14 B. Bajo and Medio Atrato ............................................................................................