A Land Title Is Not Enough

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quaternary Activity of the Bucaramanga Fault in the Depart- Ments of Santander and Cesar

Volume 4 Quaternary Chapter 13 Neogene https://doi.org/10.32685/pub.esp.38.2019.13 Quaternary Activity of the Bucaramanga Fault Published online 27 November 2020 in the Departments of Santander and Cesar Paleogene Hans DIEDERIX1* , Olga Patricia BOHÓRQUEZ2 , Héctor MORA–PÁEZ3 , 4 5 6 Juan Ramón PELÁEZ , Leonardo CARDONA , Yuli CORCHUELO , 1 [email protected] 7 8 Jaír RAMÍREZ , and Fredy DÍAZ–MILA Consultant geologist Servicio Geológico Colombiano Dirección de Geoamenazas Abstract The 350 km long Bucaramanga Fault is the southern and most prominent Grupo de Trabajo Investigaciones Geodésicas Cretaceous Espaciales (GeoRED) segment of the 550 km long Santa Marta–Bucaramanga Fault that is a NNW striking left Dirección de Geociencias Básicas Grupo de Trabajo Tectónica lateral strike–slip fault system. It is the most visible tectonic feature north of latitude Paul Krugerstraat 9, 1521 EH Wormerveer, 6.5° N in the northern Andes of Colombia and constitutes the western boundary of the The Netherlands 2 [email protected] Maracaibo Tectonic Block or microplate, the southeastern boundary of the block being Servicio Geológico Colombiano Jurassic Dirección de Geoamenazas the right lateral strike–slip Boconó Fault in Venezuela. The Bucaramanga Fault has Grupo de Trabajo Investigaciones Geodésicas Espaciales (GeoRED) been subjected in recent years to neotectonic, paleoseismologic, and paleomagnetic Diagonal 53 n.° 34–53 studies that have quantitatively confirmed the Quaternary activity of the fault, with Bogotá, Colombia 3 [email protected] eight seismic events during the Holocene that have yielded a slip rate in the order of Servicio Geológico Colombiano Triassic Dirección de Geoamenazas 2.5 mm/y, whereas a paleomagnetic study in sediments of the Bucaramanga alluvial Grupo de Trabajo Investigaciones Geodésicas fan have yielded a similar slip rate of 3 mm/y. -

COLOMBIA by George A

THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF COLOMBIA By George A. Rabchevsky 1 Colombia is in the northwestern corner of South America holders of new technology, and reduces withholding taxes. and is the only South American country with coastlines on Foreign capital can be invested without limitation in all both the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean. The majestic sectors of the economy. Andes Mountains transect the country from north to south in The Government adopted a Mining Development Plan in the western portion of the country. The lowland plains 1993 as proposed by Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones en occupy the eastern portion, with tributaries of the Amazon Geociencias, Mineria y Quimica (Ingeominas), Empresa and Orinoco Rivers. Colombiana de Carbon S.A. (Ecocarbon), and Minerales de Colombia is known worldwide for its coal, emeralds, gold, Colombia S.A. (Mineralco). The plan includes seven points nickel, and platinum. Colombia was the leading producer of for revitalizing the mineral sector, such as a new simplified kaolin and a major producer of cement, ferronickel, and system for the granting of exploration and mining licenses, natural gas in Latin America. Mineral production in provision of infrastructure in mining areas, and Colombia contributed just in excess 5% to the gross environmental control. The Government lifted its monopoly domestic product (GDP) and over 45% of total exports. Coal to sell gold, allowing anyone to purchase, sell, or export the and petroleum contributed 45% and precious stones and metal. metals contributed more than 6% to the Colombian economy. In 1994, the Colombian tax office accused petroleum companies for not paying the "war tax" established by the Government Policies and Programs 1992 tax reform. -

Publication Information

PUBLICATION INFORMATION This is the author’s version of a work that was accepted for publication in the Oryx journal. Changes resulting from the publishing process, such as peer review, editing, corrections, structural formatting, and other quality control mechanisms may not be reflected in this document. Changes may have been made to this work since it was submitted for publication. A definitive version was subsequently published in http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0030605315001118. Digital reproduction on this site is provided to CIFOR staff and other researchers who visit this site for research consultation and scholarly purposes. Further distribution and/or any further use of the works from this site is strictly forbidden without the permission of the Oryx journal. You may download, copy and distribute this manuscript for non-commercial purposes. Your license is limited by the following restrictions: 1. The integrity of the work and identification of the author, copyright owner and publisher must be preserved in any copy. 2. You must attribute this manuscript in the following format: This is an accepted version of an article by Nathalie Van Vliet, Maria Quiceno, Jessica Moreno, Daniel Cruz, John E. Fa And Robert Nasi. 2016. Is urban bushmeat trade in Colombia really insignificant?. Oryx. DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0030605315001118 Accepted Oryx Urban bushmeat trade in different ecoregions in Colombia NATHALIE VAN VLIET, MARIA QUICENO, JESSICA MORENO, DANIEL CRUZ, JOHN E. FA and ROBERT NASI NATHALIE VAN VLIET (corresponding author), and ROBERT NASI, Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), CIFOR Headquarters, Bogor 16115, Indonesia E-mail [email protected] JOHN E. -

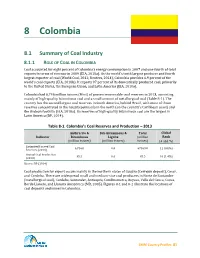

Chapter 8: Colombia

8 Colombia 8.1 Summary of Coal Industry 8.1.1 ROLE OF COAL IN COLOMBIA Coal accounted for eight percent of Colombia’s energy consumption in 2007 and one-fourth of total exports in terms of revenue in 2009 (EIA, 2010a). As the world’s tenth largest producer and fourth largest exporter of coal (World Coal, 2012; Reuters, 2014), Colombia provides 6.9 percent of the world’s coal exports (EIA, 2010b). It exports 97 percent of its domestically produced coal, primarily to the United States, the European Union, and Latin America (EIA, 2010a). Colombia had 6,746 million tonnes (Mmt) of proven recoverable coal reserves in 2013, consisting mainly of high-quality bituminous coal and a small amount of metallurgical coal (Table 8-1). The country has the second largest coal reserves in South America, behind Brazil, with most of those reserves concentrated in the Guajira peninsula in the north (on the country’s Caribbean coast) and the Andean foothills (EIA, 2010a). Its reserves of high-quality bituminous coal are the largest in Latin America (BP, 2014). Table 8-1. Colombia’s Coal Reserves and Production – 2013 Anthracite & Sub-bituminous & Total Global Indicator Bituminous Lignite (million Rank (million tonnes) (million tonnes) tonnes) (# and %) Estimated Proved Coal 6,746.0 0.0 67469.0 11 (0.8%) Reserves (2013) Annual Coal Production 85.5 0.0 85.5 10 (1.4%) (2013) Source: BP (2014) Coal production for export occurs mainly in the northern states of Guajira (Cerrejón deposit), Cesar, and Cordoba. There are widespread small and medium-size coal producers in Norte de Santander (metallurgical coal), Cordoba, Santander, Antioquia, Cundinamarca, Boyaca, Valle del Cauca, Cauca, Borde Llanero, and Llanura Amazónica (MB, 2005). -

Colombia Santa Rita Huila Organic

Colombia Santa Rita Huila Organic This Organic coffee is the result of the hard work and effort of around 84 smallholder producers living in and around the town of Santa Rita in the municipality of Aipe in Colombia’s Huila Department. With a classic Nutella-like profile and plum fruitiness, this group lot is a great go-to for your seasonal espresso blend. COFFEE GRADE: EXC.EP FW Organic FARM/COOP/STATION: Asopcafa VARIETAL: Castillo, Catuaí, Caturra, Typica PROCESSING: Fully washed ALTITUDE: 1,500 to 1,980 metres above sea level OWNER: Various smallholder farmers SUBREGION/TOWN: Santa Rita, Aipe REGION: Huila FARM SIZE: 3.5 hectares on average BAG SIZE: 70 kg GrainPro CERTIFICATIONS: Organic HARVEST MONTHS: Year-round, depending on the region The Asociación de Productores, Transformadores y Exportadores de Café Del Municipio de Aipe (Asopcafa) is a young organisation who are making great coffee strides in Colombia’s famous coffee-growing Department of Huila. Asopcafa was formed in 2013 by 88 coffee growers living in and around the municipality of Aipe. The growers, above all, sought to promote agriculture (in particular, coffee) as a means of human development in the region. Like much of rural Colombia, Huila was heavily affected by the Colombian Armed Conflict of the 1990s and early 2000s. FARC guerrillas took over huge swaths of Northern Nariño and neighbouring Tolima & Cauca, creating a corridor of migration into Huila as families fled FARC control and the ensuing violence. Governmental presence was limited, the FARC had a heavy hand in the local economy, and families and communities had great difficulties making ends meet. -

Geological Occurrence of the Ecce Homo Hill´S Cave, Chimichagua (Cesar), Colombia: an Alternative for Socio-Economic Development Based on Geotourism

International Journal of Hydrology Review Article Open Access Geological occurrence of the ecce homo hill´s cave, chimichagua (cesar), Colombia: an alternative for socio-economic development based on geotourism Abstract Volume 2 Issue 5 - 2018 This work presents the results of the speleological study developed in the Ecce Homo Ciro Raúl Sánchez-Botello,1 Gabriel Jiménez- Cerro Cave located in the southwest of the central subregion of the Cesar department, Velandia,1 Carlos Alberto Ríos-Reyes,1 Dino in the Colombian Caribbean region, associated with carbonated rocks of the Aguas 2 Blancas Formation belonging to the Cogollo Group, which have suffered Chemical Carmelo Manco-Jaraba, Elías Ernesto Rojas- 2 and mechanical dissolution generating endocárstico and exocárstico environments. In Martínez, Oscar Mauricio Castellanos- the cavern were found different types of pavillian, paving and zenith speleothems of Alarcón3 different sizes in the galleries, being this the tourist attraction of such cavity, such as 1Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia columns, moonmilk, stalactites, castings, sawtooth, gours and flags. Lithologically, 2Fundación Universitaria del Área Andina, Valledupar, Colombia this geological unit is constituted by gray, biomicritic and dismicríticas limestones 3Programa de Geología, Universidad de Pamplona, Pamplona, with high fossiliferous content, intercalations of shales, recrystallized sediments with Colombia calcium carbonate, pellets and shells recrystallized with calcium carbonate. The Ecce Carlos Alberto Ríos-Reyes, Universidad Homo Cerro Cave can be catalogued as a punctual Geosite with geomorphological Correspondence: Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia, interest, taking into account the large number and variety of speleothems presented as Email [email protected] well as its excellent state of preservation. -

Informe Final Pedro Cantillo.Pdf

Análisis de los impactos climáticos sobre la producción agropecuaria en el municipio de SitioNuevo en el departamento del Magdalena. Pedro José Cantillo García Universidad Magdalena Facultad de Ciencias Empresariales y Económicas Programa de Economía Santa Marta, Colombia 2020 Análisis de los impactos climáticos sobre la producción agropecuaria en el municipio de SitioNuevo en el departamento del Magdalena. Pedro José Cantillo García Trabajo presentado como requisito parcial para optar al título de: Economista Director: Msc. Jaime Alberto Morón Cárdenas Codirector: Msc. Niver Alberto Quiroz Mora Línea de Investigación: Desarrollo, Crecimiento y Sociedad Grupo de Investigación: Grupo de Análisis en Ciencias Económicas - GACE Facultad de Ciencias Empresariales y Económicas Programa de Economía Santa Marta, Colombia 2020 Nota de aceptación: Aprobado por el Consejo de Programa en cumplimiento de los requisitos exigidos por la Universidad del Magdalena para optar al título de Economista Jurado Jurado Santa Marta, ____ de ____del ________ Resumen A partir del desarrollo del corredor vial estratégico Palermo-Fundación, que atravesará cuatro municipios de la Subregión Río (Pivijay, Salamina, Remolino y Sitio Nuevo) y uno de la Subregión Norte (Fundación) del Departamento; el Mello planea posicionar a Palermo como un elemento determinante en la materialización del gran ‘Sueño Caribe’. El panorama económico y comercial actual del Magdalena, presenta un cúmulo de oportunidades que pueden contribuir al crecimiento económico del departamento y de esta forma aumentar el bienestar de sus habitantes; para ello se requiere que el territorio sea competitivo y pueda responder de forma exitosa a los grandes retos y desafíos del entorno económico internacional. El municipio de SitioNuevo, hoy por hoy vive un crecimiento regular por la dinámica que le imprime la economía de la región, siendo esto un gran reto: Que el desarrollo del Municipio sea sostenible y que el crecimiento mantenga el equilibrio de los ecosistemas naturales. -

Colombia Page 1 of 21

Colombia Page 1 of 21 Colombia Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2006 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 6, 2007 Colombia is a constitutional, multiparty democracy with a population of approximately 42 million. On May 28, independent presidential candidate Alvaro Uribe was reelected in elections that were considered generally free and fair. The 42-year internal armed conflict continued between the government and terrorist organizations, particularly the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN). .The United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) was demobilized by August, but renegade AUC members who did not demobilize, or who demobilized but later abandoned the peace process, remained the object of military action. While civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces, there were instances in which elements of the security forces acted in violation of state policy. Although serious problems remained, the government's respect for human rights continued to improve, which was particularly evident in actions undertaken by the government's security forces and in demobilization negotiations with the AUC. The following societal problems and governmental human rights abuses were reported during the year: unlawful and extrajudicial killings; forced disappearances; insubordinate military collaboration with criminal groups; torture and mistreatment of detainees; overcrowded and insecure prisons; arbitrary arrest; high number of -

RESOLUCIÓN DEFENSORIAL No. 55

RESOLUCIÓN DEFENSORIAL No. 55 SITUACIÓN AMBIENTAL Y DE SERVICIOS PÚBLICOS EN LOS PUEBLOS PALAFÍTICOS DE LA CIÉNAGA GRANDE DE SANTA MARTA Santa Marta, diciembre de 2008 VISTOS: 1. La Defensoría del Pueblo, en ejercicio de su misión constitucional y legal, tuvo conocimiento de la presunta vulneración de los derechos colectivos y del ambiente de los habitantes de los pueblos palafíticos y del ecosistema de la Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta. 2. En razón de lo anterior, se realizó la acción defensorial tendiente a la protección de los derechos colectivos al goce de un ambiente sano, a la existencia del equilibrio ecológico y el manejo y aprovechamiento racional de los recursos, a la seguridad y salubridad públicas, al acceso a una infraestructura de servicios que asegure la salubridad pública y al acceso a los servicios públicos y a que su prestación sea eficiente y oportuna, con el fin de garantizar los derechos humanos vinculados a su conservación. CONSIDERANDO: Primero. LA COMPETENCIA DE LA DEFENSORÍA DEL PUEBLO. 1. Es competencia de la Defensoría del Pueblo velar por el ejercicio y vigencia de los derechos humanos, de conformidad con el artículo 282 de la Constitución Política. 2. Le corresponde al Defensor del Pueblo hacer las recomendaciones y observaciones a las autoridades y a los particulares en caso de amenaza o violación a los derechos humanos, de acuerdo con el artículo 9, ordinal tercero, de la Ley 24 de 1992. 3. Es prerrogativa del Defensor del Pueblo apremiar a la comunidad en general para que se abstenga de desconocer los derechos colectivos y del ambiente, de acuerdo con lo dispuesto en el artículo 9, ordinal quinto, de la Ley 24 de 1992. -

Upper Cretaceous Chondrichthyes Teeth Record in Phosphorites of the Loma Gorda Formation•

BOLETIN DE CIENCIAS DE LA TIERRA http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/rbct Upper Cretaceous chondrichthyes teeth record in phosphorites of the • Loma Gorda formation Alejandro Niño-Garcia, Juan Diego Parra-Mosquera & Peter Anthony Macias-Villarraga Departamento de Geociencias, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Exactas, Universidad de Caldas, Manizales, Colombia. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Received: April 26th, 2019. Received in revised form: May 17th, 2019. Accepted: June 04th, 2019. Abstract In layers of phosphorites and gray calcareous mudstones of the Loma Gorda Formation, in the vicinity of the municipal seat of Yaguará in Huila department, Colombia, were found fossils teeth of chondrichthyes, these were extracted from the rocks by mechanical means, to be compared with the species in the bibliography in order to indentify them. The species were: Ptychodus mortoni (order Hybodontiformes), were found, Squalicorax falcatus and Cretodus crassidens (order Lamniformes). This finding constitutes the first record of these species in the Colombian territory; which allows to extend its paleogeographic distribution to the northern region of South America, which until now was limited to Africa, Europe, Asia and North America, except for the Ptychodus mortoni that has been described before in Venezuela. Keywords: first record; sharks; upper Cretaceous; fossil teeth; Colombia. Registro de dientes de condrictios del Cretácico Superior en fosforitas de la formación Loma Gorda Resumen En capas de fosforitas y lodolitas calcáreas grises de la Formación Loma Gorda, en cercanías de la cabecera municipal de Yaguará en el departamento del Huila, Colombia, se encontraron dientes fósiles de condrictios; estos fueron extraídos de la roca por medios mecánicos, para ser comparados con las especies encontradas en la bibliografía e identificarlos. -

Diagnóstico Departamental Magdalena

Diagnóstico Departamental Magdalena Procesado y georeferenciado por el Observatorio del Programa Presidencial de DDHH y DIH Vicepresidencia de la República Fuente base cartográfica: Igac Introducción El departamento del Magdalena está ubicado en el 350.876 en las zonas rurales. Su capital, Santa norte del país, limita por el norte con el mar Marta, tiene la mayor concentración poblacional Caribe, por el oriente con los departamentos de La con 414.387 personas (36% del total), distribuida Guajira y Cesar, por el occidente y sur con Bolívar en 384.189 habitantes en el casco urbano y y Atlántico, de los cuales está separado por la 30.198 en la zona rural. Entre la población que se cuenca del río Magdalena. El Magdalena está encuentra ubicada en el departamento, también integrado por 30 municipios y de acuerdo con el están algunas comunidades indígenas que se censo poblacional realizado por el Departamento sitúan en la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta y en sus Nacional de Estadística – Dane - en 2005, el municipios del piedemonte. Las etnias presentes departamento tiene 1.136.901 habitantes, de los en la zona son los Arhuaco, los Kogui, los Chimila y cuales 786.025 se ubican en los cascos urbanos y los Arzario, en menor proporción. 1 Diagnóstico Departamental Magdalena Nombre de Urbano Rural Total Nombre de Urbano Rural Total municipio o (Cabecera) (Resto) municipio o (Cabecera) (Resto) corregimiento corregimiento Santa Marta 384189 30198 414387 Pijiño del 6308 7542 13850 Algarrobo 7319 4237 11556 Pivijay 19079 19228 38307 Aracataca 19915 15014 -

190205 USAID Colombia Brief Final to Joslin

COUNTRY BRIEF I. FRAGILITY AND CLIMATE RISKS II.COLOMBIA III. OVERVIEW Colombia experiences very high climate exposure concentrated in small portions of the country and high fragility stemming largely from persistent insecurity related to both longstanding and new sources of violence. Colombia’s effective political institutions, well- developed social service delivery systems and strong regulatory foundation for economic policy position the state to continue making important progress. Yet, at present, high climate risks in pockets across the country and government mismanagement of those risks have converged to increase Colombians’ vulnerability to humanitarian emergencies. Despite the state’s commitment to address climate risks, the country’s historically high level of violence has strained state capacity to manage those risks, while also contributing directly to people’s vulnerability to climate risks where people displaced by conflict have resettled in high-exposure areas. This is seen in high-exposure rural areas like Mocoa where the population’s vulnerability to local flooding risks is increased by the influx of displaced Colombians, lack of government regulation to prevent settlement in flood-prone areas and deforestation that has Source: USAID Colombia removed natural barriers to flash flooding and mudslides. This is also seen in high-exposure urban areas like Barranquilla, where substantial risks from storm surge and riverine flooding are made worse by limited government planning and responses to address these risks, resulting in extensive economic losses and infrastructure damage each year due to fairly predictable climate risks. This brief summarizes findings from a broader USAID case study of fragility and climate risks in Colombia (Moran et al.