PUBLIC DIPLOMACY GANGNAM STYLE a Thesis Submitted to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IRAN April 2000

COUNTRY ASSESSMENT - IRAN April 2000 Country Information and Policy Unit I. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information & Policy Unit, Immigration & Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive, nor is it intended to catalogue all human rights violations. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a 6-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum producing countries in the United Kingdom. 1.5 The assessment will be placed on the Internet (http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/ind/cipu1.htm). An electronic copy of the assessment has been made available to the following organisations: Amnesty International UK Immigration Advisory Service Immigration Appellate Authority Immigration Law Practitioners' Association Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants JUSTICE Medical Foundation for the care of Victims of Torture Refugee Council Refugee Legal Centre UN High Commissioner for Refugees CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.6 II GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.2 -

Mujahideen-E Khalq (MEK) Dossier

Mujahideen-e Khalq (MEK) Dossier CENTER FOR POLICING TERRORISM “CPT” March 15, 2005 PREPARED BY: NICOLE CAFARELLA FOR THE CENTER FOR POLICING TERRORISM Executive Summary Led by husband and wife Massoud and Maryam Rajavi, the Mujahideen-e Khalq (MEK) is the primary opposition to the Islamic Republic of Iran; its military wing is the National Liberation Army (NLA), and its political arm is the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI). The US State Department designated the MEK as a foreign terrorist organization in 1997, based upon its killing of civilians, although the organization’s opposition to Iran and its democratic leanings have earned it support among some American and European officials. A group of college-educated Iranians who were opposed to the pro-Western Shah in Iran founded the MEK in the 1960s, but the Khomeini excluded the MEK from the new Iranian government due to the organization’s philosophy, a mixture of Marxism and Islamism. The leadership of the MEK fled to France in 1981, and their military infrastructure was transferred to Iraq, where the MEK/NLA began to provide internal security services for Saddam Hussein and the MEK received assistance from Hussein. During Operation Iraqi Freedom, however, Coalition forces bombed the MEK bases in Iraq, in early April of 2003, forcing the MEK to surrender by the middle of April of the same year. Approximately 3,800 members of the MEK, the majority of the organization in Iraq, are confined to Camp Ashraf, their main compound near Baghdad, under the control of the US-led Coalition forces. -

U.S. International Broadcasting Informing, Engaging and Empowering

2010 Annual Report U.S. International Broadcasting Informing, Engaging and Empowering bbg.gov BBG languages Table of Contents GLOBAL EASTERN/ English CENTRAL Letter From the Broadcasting Board of Governors 5 (including EUROPE Learning Albanian English) Bosnian Croatian AFRICA Greek Afan Oromo Macedonian Amharic Montenegrin French Romanian Hausa to Moldova Kinyarwanda Serbian Kirundi Overview 6 Voice of America 14 Ndebele EURASIA Portuguese Armenian Shona Avar Somali Azerbaijani Swahili Bashkir Tigrigna Belarusian Chechen CENTRAL ASIA Circassian Kazakh Crimean Tatar Kyrgyz Georgian Tajik Russian Turkmen Tatar Radio Free Europe Radio and TV Martí 24 Uzbek Ukrainian 20 EAST ASIA LATIN AMERICA Burmese Creole Cantonese Spanish Indonesian Khmer NEAR EAST/ Korean NORTH AFRICA Lao Arabic Mandarin Kurdish Thai Turkish Tibetan Middle East Radio Free Asia Uyghur 28 Broadcasting Networks 32 Vietnamese SOUTH ASIA Bangla Dari Pashto Persian Urdu International Broadcasting Board On cover: An Indonesian woman checks Broadcasting Bureau 36 Of Governors 40 her laptop after an afternoon prayer (AP Photo/Irwin Fedriansyah). Financial Highlights 43 2 Letter From the Broadcasting Board of Governors 5 Voice of America 14 “This radio will help me pay closer attention to what’s going on in Kabul,” said one elder at a refugee camp. “All of us will now be able to raise our voices more and participate in national decisions like elections.” RFE’s Radio Azadi distributed 20,000 solar-powered, hand-cranked radios throughout Afghanistan. 3 In 2010, Alhurra and Radio Sawa provided Egyptians with comprehensive coverage of the Egyptian election and the resulting protests. “Alhurra was the best in exposing the (falsification of the) Egyptian parliamentary election.” –Egyptian newspaper Alwafd (AP Photo/Ahmed Ali) 4 Letter from the Board TO THE PRESIDENT AND THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES On behalf of the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) and pursuant to Section 305(a) of Public Law 103-236, the U.S. -

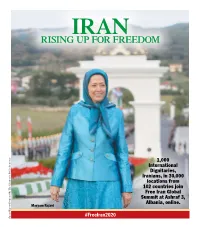

Rising up for Freedom

IRAN RISING UP FOR FREEDOM 1,000 International Dignitaries, Iranians, in 30,000 locations from 102 countries join Free Iran Global Summit at Ashraf 3, Albania, online. Maryam Rajavi #FreeIran2020 Special Report Sponsored The by Alliance Public for Awareness Iranian dissidents rally for regime change in Tehran BY BEN WOLFGANG oppressive government that has ruled Iran from both political parties participating has proven it can’t deliver for its people. tHe WasHInGtOn tImes since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Leaders represented a who’s who list of American “The Iranian people want change, to of the NCRI, which is comprised of multiple “formers,” including former Sen. Joseph I. have democracy, finally to have human Iran’s theocracy is at the weakest point other organizations, say the council has seen Lieberman of Connecticut, former Penn- rights, to finally have economic wealth, of its four-decade history and facing un- its stature grow to the point that Iranian sylvania Gov. Tom Ridge, former Attorney no more hunger. The will of the people precedented challenges from a courageous officials can no longer deny its influence. General Michael Mukasey, retired Marine is much stronger than any oppressive citizenry hungry for freedom, Iranian dis- The NCRI has many American support- Commandant James T. Conway and others. measure of an Iranian regime,” said Martin sidents and prominent U.S. and European ers, including some with close relationships Several current U.S. officials also delivered Patzelt, a member of German Parliament. politicians said Friday at a major interna- to Mr. Trump, such as former New York remarks, including Sen. -

Iran, Gulf Security, and U.S. Policy

Iran, Gulf Security, and U.S. Policy Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs August 14, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32048 Iran, Gulf Security, and U.S. Policy Summary Since the Islamic Revolution in Iran in 1979, a priority of U.S. policy has been to reduce the perceived threat posed by Iran to a broad range of U.S. interests, including the security of the Persian Gulf region. In 2014, a common adversary emerged in the form of the Islamic State organization, reducing gaps in U.S. and Iranian regional interests, although the two countries have often differing approaches over how to try to defeat the group. The finalization on July 14, 2015, of a “Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action” (JCPOA) between Iran and six negotiating powers could enhance Iran’s ability to counter the United States and its allies in the region, but could also pave the way for cooperation to resolve some of the region’s several conflicts. During the 1980s and 1990s, U.S. officials identified Iran’s support for militant Middle East groups as a significant threat to U.S. interests and allies. A perceived potential threat from Iran’s nuclear program emerged in 2002, and the United States orchestrated broad international economic pressure on Iran to try to ensure that the program is verifiably confined to purely peaceful purposes. The international pressure contributed to the June 2013 election as president of Iran of the relatively moderate Hassan Rouhani, who campaigned as an advocate of ending Iran’s international isolation. -

Iran March 2009

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT IRAN 17 MARCH 2009 UK Border Agency COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE IRAN 17 MARCH 2009 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN IRAN, FROM 2 FEBRUARY 2009 TO 16 MARCH 2009 REPORTS ON IRAN PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 2 FEBRUARY 2009 TO 16 MARCH 2009 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ......................................................................................... 1.01 Maps .............................................................................................. 1.03 Iran............................................................................................. 1.03 Tehran ....................................................................................... 1.04 2. ECONOMY ............................................................................................ 2.01 Sanctions ...................................................................................... 2.13 3. HISTORY ............................................................................................... 3.01 Calendar ........................................................................................ 3.02 Pre 1979......................................................................................... 3.03 1979 to 1999 .................................................................................. 3.05 2000 to date................................................................................... 3.16 Student unrest ............................................................................. -

The Daily Show På Persisk

10 # 08 25. februar 2011 Ideer We e ke n d av i s e n Humor som våben. Det satiriske show Parazit på Voice of America har et solidt tag i Irans enorme unge befolkning. Men det er bare ét af tegnene på, at eksilbefolkning og iransk opposition rykker stadig tættere sammen. The Daily Show på persisk Af METTE HEDEMAND SØLTOFT INTERESSEN for at undersøge forholdet Cand.mag. i persisk imellem den iranske diaspora og Iran afspejles i et stigende antal videnskabelige artikler, der ’Der er ingen bøsser i Iran’, erklærede også viser, at eksiliranerne generelt er bemær- præsident Ahmedinejad foran uni- kelsesværdigt veluddannede og ofte godt »versitetet i Columbia, et af verdens integrerede i de lande og samfund, de har slået mest respekterede universiteter.« sig ned i. Man kan registrere en udvikling i Saman Arbabi fra tv-showet Parazit holder mentaliteten i den ellers religiøst og politisk en kunstpause og slår ud med armene: »Mere set meget uhomogene iranske diaspora. I behøver man ikke – så har man et show!« 1980erne, skriver professor Halleh Ghorashi Parazit er et godt eksempel på den dialog, og lektor Kees Boersma fra Vrije Universiteit der i dag foregår mellem iranerne i diasporaen Amsterdam, var diasporaen præget af had til og iranerne i Iran. Det satiriske persiskspro- styret i Iran, og venstreorienterede grupper gede tv-show sendes fra Voice of America, og satte dagsordenen. Fra eksilet så man tilbage selvom det iranske makkerpar Kambiz Hos- på Iran, som betragtedes som en »såret fugl« seini og Saman Arbabi kun sender en gang om med et såret folk. -

People's Mujahedin of Iran - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

People's Mujahedin of Iran - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/People's_Mujahedin_of_Iran People's Mujahedin of Iran From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The People's Mojahedin of Iran or the Mojahedin-e-Khalq People's Mojahedin Organization ﺳﺎزﻣﺎن ﻣﺠﺎھﺪﯾﻦ ﺧﻠﻖ اﯾﺮان :MEK , also PMOI , MKO ; Persian) ā ā ā ā ﺳﺎزﻣﺎن ﻣﺠﺎھﺪﯾﻦ ﺧﻠﻖ اﯾﺮان s zm n-e moj hedin-e khalq-e ir n) is an Iranian opposition movement in exile that advocates the overthrow of the Islamic Republic of Iran.[2] General Secretary Masoud Rajavi President Maryam Rajavi [1] It was founded on September 5, 1965 by a group of Founder Mohammad Hanifnejad left-leaning Muslim Iranian university students, as a Muslim, Founded September 5, 1965 progressive, nationalist and democratic organization, [3] who were devoted to armed struggle against the Shah of Iran and Headquarters Camp Liberty, Iraq Paris, France his supporters. [4] They committed several violent attacks against the Shah's regime and US officials stationed in Iran Ideology Iranian nationalism during the 1970s. In the immediate aftermath of the 1979 Islamic socialism Islamic Revolution, the MEK was suppressed by Khomeini's Left-wing nationalism revolutionary organizations and harassed by the Hezbollahi, Political position Left-wing who attacked meeting places, bookstores, and kiosks of the Colours ‹See Tfm› Red [5] Mujahideen. Party flag On 30 August 1981, the MEK launched a campaign of attacks against the Iranian government, exploding a bomb in a meeting of the Islamic Republic Party and killing 81 members of the party, including President Mohammad-Ali Rajai, Prime Minister Mohammad Javad Bahonar, and many other high-ranking officials, in the government. -

Bbg.Gov BBG Languages Table of Contents

2011 Annual Report U.S. INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING Impact through Innovation and Integration bbg.gov BBG languages Table of Contents GLOBAL EASTERN/ Letter From the Broadcasting Board of Governors 5 English CENTRAL (including EUROPE Learning Albanian English) Bosnian Croatian AFRICA Greek Afaan Oromoo Macedonian Amharic Montenegrin French Romanian Hausa to Moldova Kinyarwanda Serbian International Kirundi Overview 6 Broadcasting Bureau 16 Ndebele EURASIA Portuguese Armenian Shona Avar Somali Azerbaijani Swahili Bashkir Tigrigna Belarusian Chechen CENTRAL ASIA Circassian Kazakh Crimean Tatar Kyrgyz Georgian Tajik Russian Turkmen Tatar Voice of America 22 Radio Free Europe/ Uzbek Ukrainian Radio Liberty 28 EAST ASIA LATIN AMERICA Burmese Creole Cantonese Spanish Indonesian Khmer NEAR EAST/ Korean NORTH AFRICA Lao Arabic Mandarin Kurdish Thai Turkish Tibetan Radio Free Asia 36 Uyghur Radio and TV Martí 32 SOUTH ASIA Vietnamese Bangla Dari Pashto Persian Urdu Middle East Broadcasting Board On cover: Tarek El-Shamy of Alhurra TV interviews Broadcasting Networks 40 of Governors 44 a protester in Tahrir Square in Cairo. Financial Highlights 47 2 Letter From the Broadcasting Board of Governors 5 [Steve Herman’s tweets]..have kept us ahead of the curve in reporting “aftershocks, tsunami effects and nuclear crisis developments. –Australian Broadcasting Corporation article titled “Journalism’s New Wave, the World in a Tweet” ” VOA correspondent Steve Herman was one of the first American reporters to report from the “depopulated zone” around the crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. 3 Alhurra, Radio Sawa, Afia Darfur and the Voice of America were on hand as the people of South Sudan voted in January 2011 to form a new nation and made their first halting steps toward independence. -

U.S. Public Diplomacy Towards Iran During the George W

U.S. PUBLIC DIPLOMACY TOWARDS IRAN DURING THE GEORGE W. BUSH ERA A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of PhD to the Department of History and Cultural Studies of the Freie Universität Berlin by Javad Asgharirad Date of the viva voce/defense: 05.01.2012 First examiner: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Ursula Lehmkuhl Second examiner: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Nicholas J. Cull i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My greatest thanks go to Prof. Ursula Lehmkuhl whose supervision and guidance made it possible for me to finish the current work. She deserves credit for any virtues the work may possess. Special thanks go to Nicholas Cull who kindly invited me to spend a semester at the University of Southern California where I could conduct valuable research and develop academic linkages with endless benefits. I would like to extend my gratitude to my examination committee, Prof. Dr. Claus Schönig, Prof. Dr. Paul Nolte, and Dr. Christoph Kalter for taking their time to read and evaluate my dissertation here. In the process of writing and re-writing various drafts of the dissertation, my dear friends and colleagues, Marlen Lux, Elisabeth Damböck, and Azadeh Ghahghaei took the burden of reading, correcting, and commenting on the rough manuscript. I deeply appreciate their support. And finally, I want to extend my gratitude to Pier C. Pahlavi, Hessamodin Ashena, and Foad Izadi, for sharing with me the results of some of their academic works which expanded my comprehension of the topic. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS II LIST OF TABLES, FIGURES AND IMAGES V LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS VI ABSTRACT VII INTRODUCTION 1 STATEMENT OF THE TOPIC 2 SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY AND QUESTIONS 2 LITERATURE SURVEY 4 UNDERSTANDING PUBLIC DIPLOMACY:DEFINING THE TERM 5 Public Diplomacy Instruments 8 America’s Public Diplomacy 11 CHAPTER OUTLINE 14 1. -

Iran: U.S. Concerns and Policy Responses

Iran: U.S. Concerns and Policy Responses Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs October 26, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32048 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Iran: U.S. Concerns and Policy Responses Summary The Obama Administration views Iran as a major threat to U.S. national security interests, a perception generated by uncertainty about Iran’s intentions for its nuclear program as well as its materiel assistance to armed groups in Iraq and Afghanistan, to the Palestinian group Hamas, and to Lebanese Hezbollah. Since mid-2011, U.S. officials have openly accused Iran of stepping up support for Iraqi Shiite militias that have attacked U.S. forces, and U.S. officials accused Iran in October 2011 of plotting to assassinate the Saudi Ambassador to the United States. U.S. officials also accuse Iran of helping Syria’s leadership try to defeat a growing popular opposition movement, and of taking advantage of Shiite majority unrest against the Sunni-led, pro-U.S. government of Bahrain. The Obama Administration initially offered Iran’s leaders consistent and sustained engagement with the potential for closer integration with and acceptance by the West in exchange for limits to its nuclear program. After observing a crackdown on peaceful protests in Iran in 2009, and failing to obtain Iran’s agreement to implement any nuclear compromise, the Administration has worked since early 2010 to increase economic and diplomatic pressure on Iran. Significant additional sanctions were imposed on Iran by the U.N. Security Council (Resolution 1929), as well as related “national measures” by the European Union, Japan, South Korea, and other countries. -

BBG) Board from January 2012 Through July 2015

Description of document: Monthly Reports to the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) Board from January 2012 through July 2015 Requested date: 16-June-2017 Released date: 25-August-2017 Posted date: 02-April-2018 Source of document: BBG FOIA Office Room 3349 330 Independence Ave. SW Washington, D.C. 20237 Fax: (202) 203-4585 The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. Broadcasting 330 Independence Ave.SW T 202.203.4550 Board of Cohen Building, Room 3349 F 202.203.4585 Governors Washington, DC 20237 Office of the General Counsel Freedom of Information and Privacy Act Office August 25, 2017 RE: Request Pursuant to the Freedom of Information Act - FOIA #17-058 This letter is in response to your Freedom of Information Act .(FOIA) request dated June 16, 2017 to the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG), which the Agency received on June 20, 2017.