The Arakan Valley Experience an Integrated Sectoral Programming in Building Resilience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Resilience, Pathways and Circumstances: Unpicking livelihood threats and responses in the rural Philippines. JORDAN, GEORGINA,NORA,MARY How to cite: JORDAN, GEORGINA,NORA,MARY (2012) Resilience, Pathways and Circumstances: Unpicking livelihood threats and responses in the rural Philippines., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4433/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Resilience, Pathways and Circumstances: Unpicking livelihood threats and responses in the rural Philippines. Georgina Nora Mary Jordan The response of small scale agricultural producers in the Philippines to livelihood threats arising from market integration has received less attention than responses to other threats. The ability of agricultural producers to respond to changes in their production environment is an important component of livelihood resilience. This research unravels the patterns of livelihood response used by small scale agricultural producers in the Philippines affected by livelihood threats resulting from changes in their production environment as a result of agricultural trade liberalisation. -

Department of Science and Technology Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY PHILIPPINE INSTITUTE OF VOLCANOLOGY AND SEISMOLOGY UPDATE ON THE OCTOBER 2019 COTABATO FAULT SYSTEM EARTHQUAKE SERIES Update as of 08 November 2019 What is happening in Cotabato and vicinity? As of 07:00 AM Philippine Standard Time (PST) of 08 November 2019 (Friday), the total number of earthquakes recorded since the 29 October 2019 Magnitude 6.6 earthquake event is now 2226, with 917 plotted and 161 felt at various intensities. Figure 1 shows earthquake plots as of 07 November 2019 (6PM). Figure 1. Seismicity map related to the October 2019 Cotabato Fault System earthquake series (as of 07 November 2019, 6PM) Another DOST-PHIVOLCS Quick Response Team (QRT), consisting of geologists, civil engineers, seismologists and information officers, was immediately deployed on 30 October 2019. The team will investigate geologic impacts, assess structural Minor earthquakes: 3 to 3.9; Light earthquakes: 4 to 4.9; Moderate earthquakes: 5 to 5.9; Strong earthquakes: 6 to 6.9; Major earthquakes: 7 to 7.9; Great earthquakes: 8.0 and above. Postal Ad Postal address: PHIVOLCS Building, C.P. Garcia Avenue, U.P. Campus Tel. Nos.: +63 2 8426-1468 to 79; +63 2 8926-2611 Diliman, Quezon City 1101 Philippines Fax Nos.: +63 2 8929-8366; +63 2 8928-3757 Website Website: www.phivolcs.dost.gov.ph 1 damages, establish additional portable seismic stations in the vicinity of the earthquake epicenters to augment existing DOST-PHIVOLCS seismic monitoring network (Figure 2) to monitor and study ongoing occurrence of earthquake events, and conduct intensity surveys and information education campaigns and briefings with local DRRMOs and residents of affected communities. -

The Participation of Government Agencies (Gas) and Civil Society Organizations (Csos) Inthe War Disaster Management Operation

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 3 No. 17; September 2013 “The Participation of Government Agencies (GAs) and Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) inthe War Disaster Management Operation in North Cotabato, Southern Philippines: A Comparative Analysis.” Dr. Radzak Abag Sam Senior Lecturer School of Social Sciences UniversitiSains Malaysia (USM) Pulau Pinang, Malaysia. Solayha Abubakar-Sam Asst. Professor College of Education Mindanao State University, Maguindanao Philippines Abstract Both Government Agencies (GAs) and Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) thatparticipated in the War Disaster Management Operation in Pikit, Aleosan, Midsayap, and Pigkawayan, North Cotabato, Southern Philippines have extended food and non- food relief assistance for the Internally Displaced Persons(IDPs)coming from those areas mentioned. In addition, Core ShelterUnits were provided for the IDPs whose houses were totally damaged during the war, while financial assistance for those whose houses were partially damaged. Clustering approach, coordination and sharing of information with other humanitarian actors, and designation of field workers were the common strategies used by both GAs and CSOs for the social preparation of IDPs for relief assistance. However, Civil Society Organizations that have no funding support wentto the extent of house to house, school to school, and solicitations through Masjid in the pursuit of their interest toextend assistance. While the readiness and prepared of IDPs for pre- disaster was low due to the slow -

Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines

Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines November 2005 Republika ng Pilipinas PAMBANSANG LUPON SA UGNAYANG PANG-ESTADISTIKA (NATIONAL STATISTICAL COORDINATION BOARD) http://www.nscb.gov.ph in cooperation with The WORLD BANK Estimation of Local Poverty in the Philippines FOREWORD This report is part of the output of the Poverty Mapping Project implemented by the National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB) with funding assistance from the World Bank ASEM Trust Fund. The methodology employed in the project combined the 2000 Family Income and Expenditure Survey (FIES), 2000 Labor Force Survey (LFS) and 2000 Census of Population and Housing (CPH) to estimate poverty incidence, poverty gap, and poverty severity for the provincial and municipal levels. We acknowledge with thanks the valuable assistance provided by the Project Consultants, Dr. Stephen Haslett and Dr. Geoffrey Jones of the Statistics Research and Consulting Centre, Massey University, New Zealand. Ms. Caridad Araujo, for the assistance in the preliminary preparations for the project; and Dr. Peter Lanjouw of the World Bank for the continued support. The Project Consultants prepared Chapters 1 to 8 of the report with Mr. Joseph M. Addawe, Rey Angelo Millendez, and Amando Patio, Jr. of the NSCB Poverty Team, assisting in the data preparation and modeling. Chapters 9 to 11 were prepared mainly by the NSCB Project Staff after conducting validation workshops in selected provinces of the country and the project’s national dissemination forum. It is hoped that the results of this project will help local communities and policy makers in the formulation of appropriate programs and improvements in the targeting schemes aimed at reducing poverty. -

List of On-Process Cadts in Region 12 (Direct CADT Applications) Date Filed/ Year CADC No./ No

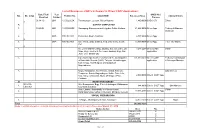

List of On-process CADTs in Region 12 (Direct CADT Applications) Date Filed/ Year CADC No./ No. No. (orig) Petition No. LOCATION Est. Area (Has.) Claimant ICC/s Received Funded Process 06-14-10 2011 12-0022-LSK Tanansangan, Lutayan, Sultan Kudarat 1,480.0000 CADC-073 B'laan 7 A. SURVEY COMPLETED 1. 04-29-04 2004 12-0025-ESK Salumping, Esperanza and Legodon Sultan Kudarat 21,228.0000 Direct App. Teduray & Manobo Dulangan 1 2. 2005 RXII-SC-008 Polomolok, South Cotabato 2,507.0000 Direct App. 5 3. 2008 RXII-SC-009 Sitio Yama, Uhay & Blacol, Ned, Lake Sebu, South 19,000.0000 Direct App. T'boli Tao-Mohin Cot 8 4. So. Lower Balnabo, Brgy. Bawing, Sos. Ulo Cabo, Ulo 3,247.2270 Direct CADT B'laan Supo, Brgy Tambler & So. Lower Aspang, Brgy. San application Jose, Gen. Santos City 5. Upi, South Upi, Southern portions of the municipalities 201,880.0000 Direct CADT Teduray/ Lambangian of Datu Odin Sinsuat (DOS), Talayan, Guindulongan, application & Dulangan Manobo Datu Unsay, Shariff Aguak and Ampatuan, Maguindanao 6. Brgys. Bongolanin, Don Panaca, Sallab, Kinarum, Obo-Manuvu Temporan, Basak, Bagumbayan, Balite, Datu Celo, Noa, Binay, & Kisandal, Muni. Of Magpet, Prov. 2,000.0000 Direct CADT App. Cotabato B READY FOR SURVEY NCIPXII- Sitio Sumayahon, Brgy. Perez & Indangan, Kidapawan 1. 644.0000 Direct CADT App. Obo-Manuvu COT-AD- City North Cotabato 024 Brgy. Landan, Municipality of Polomolok and B'laan 2. 17,976.4385 Direct CADT App. Barangays Upper Labay, Conel and Olimpog, General Santos City,SouthSOCIAL Cotabato PREPARATION 1. 28 Brgys., Municipality of Glan, Sarangani 24,977.7699 Direct CADT App. -

PALMA+PB Alliance of Municipalities

PALMA+PB Alliance of Municipalities Province of Cotabato Region X11 PALMA+PB is an acronym DERIVED FROM the first letter of the names of the municipalities that comprise the Alliance, namely: Pigcawayan Alamada Libungan Midsayap Aleosan Pikit Banisilan Pikit became a member of the alliance only last April 25, 2008 and Banisilan in August 18,2011 after one (1) year of probation as observer . PALMA+PB Alliance Luzon Alamada Banisilan Pigcawayan Visayas Libungan Aleosan Midsayap Mindanao Pikit Located in the first congressional district of Cotabato Province, Region XII in the island of Mindanao, Philippines. PALMA+PB Alliance THE CREATION OF PALMA+PB Alliance The establishment of this Alliance gets its legal basis from REPUBLIC ACT 7160 “THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT CODE OF 1991, Section 33, Art. 3, Chapter 3, which states that; “LGUs may, through appropriate ordinances, group themselves, consolidate, or ordinate their efforts, services, and resources for purposes commonly beneficial to them. In support to such undertakings, the LGUs involved may, upon approval by the Sanggunian concerned after a public hearing conducted for the purpose, contribute funds, real estate, equipment and other kinds of property and appoint or assign, personnel under such terms and conditions as may be agreed upon by the participating local units through Memoranda of Agreement (MOA).” PALMA+PB Alliance Profile Land Area :280,015.88 has. Population :393,831 Population Density :1.41 person/ha. Population by Tribe: Cebuano :30.18% Maguindanaon :25.45% Ilonggo :19.82% Ilocano :11.15% IP’s :10.55% Other Tribes :2.85% Number of Barangays :215 Number of Households :81,767 Basic Products Agricultural and Fresh Water fish PALMA+PB Alliance B. -

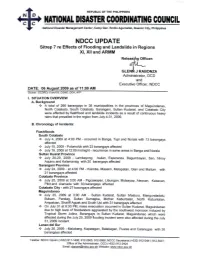

Sitrep 7 Re Effects of Flooding and Landslide in Regions XI, XII And

Davao del Sur July 31, 2009 - Jose Abad Santos and Sarangani with 3 barangays affected Landslides July 26, 2009 - along the national highway in Brgy Macasandig, Parang, Maguindanao July 30, 2009 - another one occurred along the portion of Narciso Ramos Highway in same municipality wherein huge boulders and toppled electric posts caused traffic to motorists and commuters going to and from Cotabato City and Marawi City II. EFFECTS A. Affected Population A total of 86,910 families/429,457 persons were affected in 266 barangays of 38 municipalities in 7 provinces in Regions XI and XII and 1 city. Out of the total affected 4,275 families /21,375 persons were evacuated. B. Casualties – 20 Dead Sarangani (4) – Calamagan Family (Rondy, Lynlyn, Jeffrey) in Malapatan and Bernardo Gallo in Kiamba North Cotabato (2) – Pinades Binanga in Alamada and Pining Velasco in Midsayap Maguindanao (11) – Basilia Rosaganan, Patrick Suicano, Wilfredo Lagare, Francisco Felecitas, Bai Salam Matabalao, Shaheena Nor Limadin, Hadji Ismael Datukan, Roly Usman, Lilang Ubang, Mama Nakan, So Lucuyom South Cotabato (1) – Gina Molon in Banga Cotabato City (2) – Hadja Sitte Mariam Daud-Luminda and Datu Jamil Kintog C. Damages - PhP318.257 Million INFRASTRUCTURES AGRICULTURE South Cotabato 4.30 Million 13.374 Million Cotabato Province 194.00 Million Cotabato City 10.00 Million Sarangani Province 58.40 Million Maguindanao 13.183 Million Sultan Kudarat Prov. 25.00 Million TOTAL 291.70 Million 26.557 Million III. EMERGENCY RESPONSE A. National Action The NDCC-OPCEN -

Policy Briefing

Policy Briefing Asia Briefing N°83 Jakarta/Brussels, 23 October 2008 The Philippines: The Collapse of Peace in Mindanao Once the injunction was granted, the president and her I. OVERVIEW advisers announced the dissolution of the government negotiating team and stated they would not sign the On 14 October 2008 the Supreme Court of the Philip- MOA in any form. Instead they would consult directly pines declared a draft agreement between the Moro with affected communities and implied they would Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Philippines only resume negotiations if the MILF first disarmed. government unconstitutional, effectively ending any hope of peacefully resolving the 30-year conflict in In the past when talks broke down, as they did many Mindanao while President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo times, negotiations always picked up from where they remains in office. The Memorandum of Agreement on left off, in part because the subjects being discussed Ancestral Domain (MOA-AD or MOA), the culmination were not particularly controversial or critical details of eleven years’ negotiation, was originally scheduled were not spelled out. This time the collapse, followed to have been signed in Kuala Lumpur on 5 August. At by a scathing Supreme Court ruling calling the MOA the last minute, in response to petitions from local offi- the product of a capricious and despotic process, will cials who said they had not been consulted about the be much harder to reverse. contents, the court issued a temporary restraining order, preventing the signing. That injunction in turn led to While the army pursues military operations against renewed fighting that by mid-October had displaced three “renegade” MILF commanders – Ameril Umbra some 390,000. -

FY 2019 ANNUAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROGRAM Based on General Appropriations Act

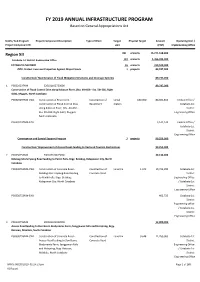

FY 2019 ANNUAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROGRAM Based on General Appropriations Act UACS / Sub Program Project Component Description Type of Work Target Physical Target Amount Operating Unit / Project Component ID Unit (PHP) Implementing Office Region XII 904 projects 15,271,108,000 Cotabato 1st District Engineering Office 124 projects 1,356,934,000 COTABATO (SECOND) 55 projects 319,500,000 OO2: Protect Lives and Properties Against Major Floods 1 projects 89,747,000 Construction/ Maintenance of Flood Mitigation Structures and Drainage Systems 89,747,000 1. P00320297MN 320101102739000 89,747,000 Construction of Flood Control Dike along Kabacan River, (Sta. 49+660 - Sta. 50+300, Right Side), Magpet, North Cotabato P00320297MN-CW1 Construction of Revetment - Construction of Lineal 640.000 86,605,855 Central Office / Construction of Flood Control Dike Revetment meters Cotabato 1st along Kabacan River, (Sta. 49+660 - District Sta. 50+300, Right Side), Magpet, Engineering Office North Cotabato P00320297MN-EAO 3,141,145 Central Office / Cotabato 1st District Engineering Office Convergence and Special Support Program 7 projects 90,253,000 Construction/ Improvement of Access Roads leading to Declared Tourism Destinations 90,253,000 2. P00330753MN 300203100613000 20,136,000 Balabag-Sito Umpang Road leading to Paniki Falls, Brgy. Balabag, Kidapawan City, North Cotabato P00330753MN-CW1 Construction of Concrete Road - Construction of Lane Km 1.342 19,733,280 Cotabato 1st Balabag-Sito Umpang Road leading Concrete Road District to Paniki Falls, Brgy. Balabag, Engineering Office Kidapawan City, North Cotabato / Cotabato 1st District Engineering Office P00330753MN-EAO 402,720 Cotabato 1st District Engineering Office / Cotabato 1st District Engineering Office 3. -

Comprehensive Capacity Development Project for the Bangsamoro Sector Report 2-3: Air Transport

Comprehensive capacity development project for the Bangsamoro Sector Report 2-3: Air Transport Comprehensive Capacity Development Project for the Bangsamoro Development Plan for the Bangsamoro Final Report Sector Report 2-3: Air Transport Comprehensive capacity development project for the Bangsamoro Sector Report 2-3: Air Transport Comprehensive capacity development project for the Bangsamoro Sector Report 2-3: Air Transport Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 3-1 1.1 Airports in Mindanao ............................................................................................................ 3-1 1.2 Classification of Airports in the Philippines ......................................................................... 3-1 1.3 Airports in Bangsamoro ........................................................................................................ 3-2 1.4 Overview of Airports in Bangsamoro ................................................................................... 3-2 1.4.1 Cotabato airport ............................................................................................................... 3-2 1.4.2 Jolo airport ....................................................................................................................... 3-3 1.4.3 Sanga-Sanga Airport ........................................................................................................ 3-3 1.4.4 Cagayan De Sulu -

NDCC UPDATE Situation Report No

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES National Disaster Management Center, Camp Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo, Quezon City, Philippines NDCC UPDATE Situation Report No. 33 on the Effects of Typhoon “FRANK” (Fengshen) Releasing Officer: GLENN J RABONZA Administrator, OCD and Executive Officer, NDCC DATE : 31 JuLY 2008 Reference: DSWD, DOH, DepEd, DPWH, PCG, TRANSCO, NEA, HQ Task Force “Frank”, DOTC, RDCCs/ OCDRCs I, III, IV-A, IV- B, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII, CARAGA, ARMM & NCR I. BACKGROUND Typhoon “Frank” entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) as a tropical depression on 18 June 2008. As it made a landfall in Eastern Visayas, it has already intensified into a typhoon. And as it move into the country, TY “Frank” had induced the southwest monsoon that caused landslides, flooding and storm surges along the eastern and western seaboards. Severely affected in terms of damage to infrastructure and the number of directly affected persons were the provinces of Iloilo , Capiz, Aklan and Antique in Region VI; and Leyte and Eastern Samar in Region VIII. Also affected by flooding due to moderate and heavy rains brought by the enhanced southwest monsoon, were the provinces of Maguidanao and Shariff Kabunsuan in ARMM; and Cotabato City and North Cotabato in Region XII. II. EFFECTS Affected Population/ Areas Affected/ Displaced Population More than nine hundred thousand families or four million persons were directly affected by TY “Frank” in 6, 377 barangays of 419 municipalities in 58 provinces of 15 regions . Region VI has the most number of affected population- 421,479 families/ 2,159,780 persons. This is 44% and 45% of the total number of families and persons affected by TY “Frank” and its associated hazards.