Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

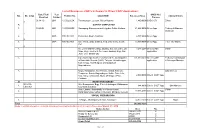

List of On-Process Cadts in Region 12 (Direct CADT Applications) Date Filed/ Year CADC No./ No

List of On-process CADTs in Region 12 (Direct CADT Applications) Date Filed/ Year CADC No./ No. No. (orig) Petition No. LOCATION Est. Area (Has.) Claimant ICC/s Received Funded Process 06-14-10 2011 12-0022-LSK Tanansangan, Lutayan, Sultan Kudarat 1,480.0000 CADC-073 B'laan 7 A. SURVEY COMPLETED 1. 04-29-04 2004 12-0025-ESK Salumping, Esperanza and Legodon Sultan Kudarat 21,228.0000 Direct App. Teduray & Manobo Dulangan 1 2. 2005 RXII-SC-008 Polomolok, South Cotabato 2,507.0000 Direct App. 5 3. 2008 RXII-SC-009 Sitio Yama, Uhay & Blacol, Ned, Lake Sebu, South 19,000.0000 Direct App. T'boli Tao-Mohin Cot 8 4. So. Lower Balnabo, Brgy. Bawing, Sos. Ulo Cabo, Ulo 3,247.2270 Direct CADT B'laan Supo, Brgy Tambler & So. Lower Aspang, Brgy. San application Jose, Gen. Santos City 5. Upi, South Upi, Southern portions of the municipalities 201,880.0000 Direct CADT Teduray/ Lambangian of Datu Odin Sinsuat (DOS), Talayan, Guindulongan, application & Dulangan Manobo Datu Unsay, Shariff Aguak and Ampatuan, Maguindanao 6. Brgys. Bongolanin, Don Panaca, Sallab, Kinarum, Obo-Manuvu Temporan, Basak, Bagumbayan, Balite, Datu Celo, Noa, Binay, & Kisandal, Muni. Of Magpet, Prov. 2,000.0000 Direct CADT App. Cotabato B READY FOR SURVEY NCIPXII- Sitio Sumayahon, Brgy. Perez & Indangan, Kidapawan 1. 644.0000 Direct CADT App. Obo-Manuvu COT-AD- City North Cotabato 024 Brgy. Landan, Municipality of Polomolok and B'laan 2. 17,976.4385 Direct CADT App. Barangays Upper Labay, Conel and Olimpog, General Santos City,SouthSOCIAL Cotabato PREPARATION 1. 28 Brgys., Municipality of Glan, Sarangani 24,977.7699 Direct CADT App. -

The Arakan Valley Experience an Integrated Sectoral Programming in Building Resilience

THE ARAKAN VALLEY EXPERIENCE AN INTEGRATED SECTORAL PROGRAMMING IN BUILDING RESILIENCE A CASE STUDY ON HOW ACTION AGAINST HUNGER INTERVENTIONS HELPED BARANGAY KINAWAYAN IN ARAKAN VaLLEY WORK TOWARDS RESILIENCE INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF RURAL RECONSTRUCTION The Arakan Valley Experience An Integrated Sectoral Programming in Building Resilience All rights reserved © 2018 Humanitarian Leadership Academy Philippines The Humanitarian Leadership Academy is a charity registered in England and Wales (1161600) and a company limited by guarantee in England and Wales (9395495). Humanitarian Leadership Academy Philippines is a branch office of the Humanitarian Leadership Academy. This publication may be reproduced by any method without fee or prior permission for teaching purposes, but not for resale. For copying in any other circumstances, prior written permission must be obtained from the publisher, and a fee may be payable. Written by International Institute of Rural Reconstruction Designed by Marleena Litton Edited by Ruby Shaira Panela Images are from the International Institute of Rural Reconstruction www.humanitarianleadershipacademy.org TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms ii Introduction 1 Arakan Valley 2 Action Against Hunger Goes to Arakan Valley 6 Fighting Malnutrition 8 Improving Food Security and Livelihood (FSL) 12 Better Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) 15 Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) 24 Gender Mainstreaming 28 Background: The Program 28 Conceptualization 28 Implementation 31 Systems and Processes to Mainstream Sectoral Programs 32 in Municipal and Barangay Level Internal Monitoring and Evaluation 35 Evidence of good practices 37 Lessons Learned 40 Annexes 42 Annex 1. Methodology 43 Annex 2. Itinerary of data gathering activity in 46 Kidapawan City, North Cotabato Annex 3. Partnership with Key Stakeholders 47 Annex 4. -

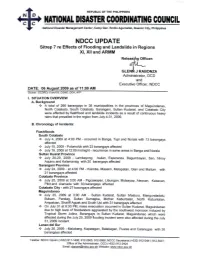

Sitrep 7 Re Effects of Flooding and Landslide in Regions XI, XII And

Davao del Sur July 31, 2009 - Jose Abad Santos and Sarangani with 3 barangays affected Landslides July 26, 2009 - along the national highway in Brgy Macasandig, Parang, Maguindanao July 30, 2009 - another one occurred along the portion of Narciso Ramos Highway in same municipality wherein huge boulders and toppled electric posts caused traffic to motorists and commuters going to and from Cotabato City and Marawi City II. EFFECTS A. Affected Population A total of 86,910 families/429,457 persons were affected in 266 barangays of 38 municipalities in 7 provinces in Regions XI and XII and 1 city. Out of the total affected 4,275 families /21,375 persons were evacuated. B. Casualties – 20 Dead Sarangani (4) – Calamagan Family (Rondy, Lynlyn, Jeffrey) in Malapatan and Bernardo Gallo in Kiamba North Cotabato (2) – Pinades Binanga in Alamada and Pining Velasco in Midsayap Maguindanao (11) – Basilia Rosaganan, Patrick Suicano, Wilfredo Lagare, Francisco Felecitas, Bai Salam Matabalao, Shaheena Nor Limadin, Hadji Ismael Datukan, Roly Usman, Lilang Ubang, Mama Nakan, So Lucuyom South Cotabato (1) – Gina Molon in Banga Cotabato City (2) – Hadja Sitte Mariam Daud-Luminda and Datu Jamil Kintog C. Damages - PhP318.257 Million INFRASTRUCTURES AGRICULTURE South Cotabato 4.30 Million 13.374 Million Cotabato Province 194.00 Million Cotabato City 10.00 Million Sarangani Province 58.40 Million Maguindanao 13.183 Million Sultan Kudarat Prov. 25.00 Million TOTAL 291.70 Million 26.557 Million III. EMERGENCY RESPONSE A. National Action The NDCC-OPCEN -

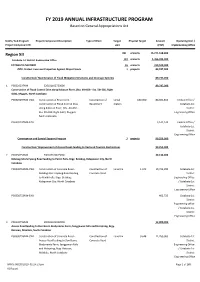

FY 2019 ANNUAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROGRAM Based on General Appropriations Act

FY 2019 ANNUAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROGRAM Based on General Appropriations Act UACS / Sub Program Project Component Description Type of Work Target Physical Target Amount Operating Unit / Project Component ID Unit (PHP) Implementing Office Region XII 904 projects 15,271,108,000 Cotabato 1st District Engineering Office 124 projects 1,356,934,000 COTABATO (SECOND) 55 projects 319,500,000 OO2: Protect Lives and Properties Against Major Floods 1 projects 89,747,000 Construction/ Maintenance of Flood Mitigation Structures and Drainage Systems 89,747,000 1. P00320297MN 320101102739000 89,747,000 Construction of Flood Control Dike along Kabacan River, (Sta. 49+660 - Sta. 50+300, Right Side), Magpet, North Cotabato P00320297MN-CW1 Construction of Revetment - Construction of Lineal 640.000 86,605,855 Central Office / Construction of Flood Control Dike Revetment meters Cotabato 1st along Kabacan River, (Sta. 49+660 - District Sta. 50+300, Right Side), Magpet, Engineering Office North Cotabato P00320297MN-EAO 3,141,145 Central Office / Cotabato 1st District Engineering Office Convergence and Special Support Program 7 projects 90,253,000 Construction/ Improvement of Access Roads leading to Declared Tourism Destinations 90,253,000 2. P00330753MN 300203100613000 20,136,000 Balabag-Sito Umpang Road leading to Paniki Falls, Brgy. Balabag, Kidapawan City, North Cotabato P00330753MN-CW1 Construction of Concrete Road - Construction of Lane Km 1.342 19,733,280 Cotabato 1st Balabag-Sito Umpang Road leading Concrete Road District to Paniki Falls, Brgy. Balabag, Engineering Office Kidapawan City, North Cotabato / Cotabato 1st District Engineering Office P00330753MN-EAO 402,720 Cotabato 1st District Engineering Office / Cotabato 1st District Engineering Office 3. -

Idp Protection Assessment Report

IDP PROTECTION ASSESSMENT REPORT Displacement due to earthquake in North Cotabato province Date: November 27, 2019 IDPPAR no. 16, Issue no. 04, 2019 INCIDENT BACKGROUND On 16th, 29th, and 31st of October 2019, a series of strong earthquakes jolted Cotabato province with magnitude 6.3, 6.6, and 6.5 respectively. The epicenter was located east of Tulunan municipality, Cotabato. The municipalities of Tulunan and Makilala, and the City of Kidapawan were among the areas that were greatly affected. Due to consecutive occurrences of earthquake, severe damage to and destruction of houses, private and government infrastructures were reported as well as scores of casualties. Government institutions have mobilized their resources to provide aid to the victims. Non-government organizations conducted assessment and response activities, and private institutions and individuals donated relief assistance. CURRENT SITUATION In Kidapawan City, a total of 2,536 families were affected, and as of November 21, are staying in 21 designated evacuation sites. On October 29, 2019, forced evacuation was conducted in Sitios Embasi, Lapan, Bagong Silang, Sumayahon, and Imbag in Bar - s which make them unsafe for habitation, according to the assessment conducted by the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources and the City Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Office (CDRRMO) of Kidapawan. In Makilala municipality, out of 38 barangays, 4 barangays were confirmed by MGB Region XII - : Barangays Cabilao, Luayon, Bato, and Buhay. In Tulunan municipality, a total of 11, 886 families were affected. According to the Municipal Social Welfare Officer, one (1) person reportedly died and 53 individuals were injured. -

An Assessment of Status and Progress of MDG Accomplishment in Region 12

Missing Targets: An alternative MDG midterm report An assessment of status and progress of MDG accomplishment in Region 12 By JOSEPH GLORIA* HIS paper tries to assess the government’s positive outlook on the attainment of the Millennium Development Goal targets in Central TMindanao. It tries to answer the question: Will government deliver on its promise on the MDG in Central Mindanao amid constant threats? What government claims The NEDA Region XII assessment on probable MDG attainment in the region gives a rosy picture. On all goals presented, the government claims a high probability of attainment in the region by 2015. Data presented supporting this assessment all point to a positive trend.1 The data are also supported by and con- sistent with by the National Statistical Coordination Board-Region 12’s MDG Statistics Capsule that provided the baseline data for 1997 and data for 2003. * Joseph Gloria is the Mindanao Coordinator of Social Watch Philippines and Assisstant Director for Visayas and Mindanao of Philippine Rural Reconstruction Movement. 1 It should be noted that most of the data presented to support this claims used 2000 as a baseline and trends ending in 2003 as an endpoint. SOCIAL WATCH PHILIPPINES 0 Missing Targets: An alternative MDG midterm report Table . NEDA RXII Assessment Goals/Targets Status of Progress Probability of Attainment Extreme poverty On track High Extreme hunger On track High Basic amenities On track High Universal primary education Lagging Low Gender equality Nearing target but slowly declining Medium Child mortality On track High Maternal health Moderate progress Medium On the other hand, a glimpse of the Neda (access to potable water, infant and maternal mortality RXII Medium Term Regional Development Plan for and malnutrition among preschool children). -

Philippines • Mindanao Response Humanitarian Situation Update 14 September 2011

Philippines • Mindanao Response Humanitarian Situation Update 14 September 2011 This report is produced by OCHA in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It was issued by OCHA Philippines. It covers the period from 5 August to 14 September 2011. The next report will be issued on or around 10 October. I. HIGHLIGHTS/KEY PRIORITIES • Clan fighting known as rido erupted anew between the commanders of Moro Islamic Liberation Front and Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Movement, displacing over 2,000 households in North Cotabato Province. Sporadic clan fighting continues to be reported in central Mindanao. • Insecurity is impeding humanitarian response to rido and other armed conflicts. • An estimated 1,700 people remain displaced by the flooding in June. Water is slow to subside in some areas in Sultan Kudarat Province, where 12,600 people can only be reached by boat. • The Mindanao Humanitarian Action Plan 2011 is 50% funded at US$16.6 million with funding support from the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF), Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Philippines, Saudi Arabia and Spain. • Early recovery and livelihood support as well as demining remain severely underfunded. II. Situation Overview CONFLICT OVERVIEW Government–MILF peace process: Whilst the exploratory peace talks between the Government of the Philippines (GPH) and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) resumed on 22 August in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, the seeming impasse that followed has brought about an atmosphere of uncertainty. During this 22nd round of peace talks, the Government presented its counter-proposal, which consists of economic development, political settlement with the MILF, and cultural-historical acknowledgement. The MILF had earlier put forward a proposal of a comprehensive peace compact in which they sought autonomy in the form of a “sub-state”, which requires constitutional amendments. -

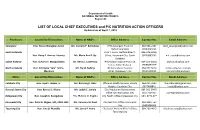

LIST of LOCAL CHIEF EXECUTIVES and P/C NUTRITION ACTION OFFICERS Updated As of April 7, 2016

Department of Health NATIONAL NUTRITION COUNCIL Region XII LIST OF LOCAL CHIEF EXECUTIVES and P/C NUTRITION ACTION OFFICERS Updated as of April 7, 2016 Provinces Local Chief Executives Name of NAO’s Office Address Contact No. Email Address Sarangani Hon. Steve Chiongbian-Solon Ms. Cornelia P. Baldelovar IPHO-Sarangani Province 083-508-2167 [email protected] Alabel, Sarangani 09393045621 South Cotabato Prov’ l. Social Welfare &Dev’t. 083-228-2184/ Hon. Daisy P. Avance- Fuentes Ms. Maria Ana D. Uy Office, Koronadal City, South 09266885635 [email protected] Cotabato Sultan Kudarat Hon. Suharto T. Mangudadatu Dr. Henry L. Lastimoso IPHO-Sultan Kudarat Province, 064-201-3032/ [email protected] Isulan, Sultan Kudarat 09088490729 North Cotabato Hon. Emmylou ”Lala” Taliño- Mr. Ely M. Nebrija IPHO-Cotabato Province 064-572-5014 [email protected] Mendoza Amas, Kidapawan City 09155119911 [email protected] Cities Local Chief Executives Name of NAO’s Office Address Contact No. Email Address Cotabato City Hon. Japal J. Guiani, Jr. Ms. BailinangC. Abas Office on Health Services, Rosary 064-421-3140 [email protected] Heights, Cotabato City 0917448816 [email protected] General Santos City Hon. Ronnel C. Rivera Ms. Judith C. Janiola City Population Management 083-302-3947/ Office, General Santos City 09177314457 [email protected] Kidapawan City Hon. Joseph A. Evangelista Ms. Melanie S. Espina City Health Office, Kidapawan City 064- 5771-377 Koronadal City Hon. Peter B. Miguel, MD, FPSO-HNS Ms. Veronica M. Daut City Nutrition Office, Koronadal 083-228-1763 City 09498494864 Tacurong City Hon. Lina O. Montilla Ms. Lorna P. Pama City Social Welfare &Dev’t Office, 064-200-4915 [email protected] Tacurong City List of Local Chief Executives & Municipal Nutrition Action Officers (SOUTH COTABATO) Municipality Mayor Name of NAO’s Office Address Contact No. -

![Solid Waste Management Sector Project (Financed by ADB's Technical Assistance Special Fund [TASF- Other Sources])](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9882/solid-waste-management-sector-project-financed-by-adbs-technical-assistance-special-fund-tasf-other-sources-3729882.webp)

Solid Waste Management Sector Project (Financed by ADB's Technical Assistance Special Fund [TASF- Other Sources])

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 45146 December 2014 Republic of the Philippines: Solid Waste Management Sector Project (Financed by ADB's Technical Assistance Special Fund [TASF- other sources]) Prepared by SEURECA and PHILKOEI International, Inc., in association with Lahmeyer IDP Consult For the Department of Environment and Natural Resources and Asian Development Bank This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR PROJECT TA-8115 PHI Final Report December 2014 In association with THE PHILIPPINES THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR PROJECT TA-8115 PHHI SR10a Del Carmen SR12: Poverty and Social SRs to RRP from 1 to 9 SPAR Dimensions & Resettlement and IP Frameworks SR1: SR10b Janiuay SPA External Assistance to PART I: Poverty, Social Philippines Development and Gender SR2: Summary of SR10c La Trinidad PART II: Involuntary Resettlement Description of Subprojects SPAR and IPs SR3: Project Implementation SR10d Malay/ Boracay SR13 Institutional Development Final and Management Structure SPAR and Private Sector Participation Report SR4: Implementation R11a Del Carmen IEE SR14 Workshops and Field Reports Schedule and REA SR5: Capacity Development SR11b Janiuay IEEE and Plan REA SR6: Financial Management SR11c La Trinidad IEE Assessment and REAE SR7: Procurement Capacity SR11d Malay/ Boracay PAM Assessment IEE and REA SR8: Consultation and Participation Plan RRP SR9: Poverty and Social Dimensions December 2014 In association with THE PHILIPPINES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................5 A. -

North-Cotabato-Ph-Corn.Pdf

124°20' 124°30' 124°40' 124°50' 125° 125°10' 125°20' 7°40' 7°40' R E P U B L I C O F T H E P H I L I P P I N E S DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Province of Lanao del Sur BUREAU OF SOILS AND WATER MANAGEMENT Elliptical Road Cor. Visayas Ave., Diliman, Quezon City SOIL pH MAP ( Key Corn Areas ) PROVINCE OF NORTH COTABATO ° SCALE 1:130,000 0 2 4 6 8 10 Kilometers Projection : Transverse Mercator Banisilan ! Datum : PRS 1992 7°30' DISCLAIMER : All political boundaries are not authoritative 7°30' Province of Bukidnon Province of Maguindanao Alamada ! Arakan ! 7°20' Province of Davao del Sur 7°20' Libungan ! Pigcawayan ! Antipas ! !Carmen !Midsayap 7°10' 7°10' !Aleosan !President Roxas Kabacan ! Province of Maguindanao Magpet Matalam ! ! Pikit ! LOCATION MAP Kidapawan \ 7° 7° Lanao Del Sur 20°0' Bukidnon LUZON 15°0' Province of Maguindanao !Makilala NORTH COTABATO !M'lang 7°0' VISAYAS 10°0' Maguindanao Davao Del Sur Sultan MINDANAO Kudarat 5°0' LEGEND South Cotabato 125°0' 120°0' 125°0' pH Value GENERAL AREA MAPPING UNIT DESCRIPTION (1:1 Ratio) RATING ha % Nearly Neutral to CONVENTIONAL SIGNS 6.9 and above; !Bagontapay Low Extremely Alkaline, 1,914 11.84 4.5 and below Province of Davao del Sur ROADS BOUNDARY HYDROLOGY Extremely Acid Expressway Regional Rivers / Lake 4.6 - 5.0 Moderately Low Very Strongly Acid 57 0.35 Trunk line Provincial Shoreline Primary City PLACES 5.1 - 5.5 Moderately High Strongly Acid 2,079 12.86 Secondary Municipal \ ^ Capital City / City Tulunan 6°50' Tertiary Moderately Acid ! 6°50' P ! Capital Town / Town 5.6 - 6.8 High 12,122 74.95 Residential to Slightly Acid TOTAL 16,172 100.00 Area estimated based on actual field survey, other information from DA-RFO's, MA's, NAMRIA Land Cover (2010) and BSWM Land Use MISCELLANEOUS INFORMATION System Map. -

Tulunan, North Cotabato Earthquakes Humanitarian Needs and Priorities November 2019 - May 2020

Philippines Humanitarian Country Team Tulunan, North Cotabato Earthquakes Humanitarian Needs and Priorities November 2019 - May 2020 Credit: OCHA/R. Maquilan Philippines: Humanitarian Humanitarian Needs and Priorities (HNP) for the Tulunan, North Cotabato Earthquakes (November 2019 - May 2020) Key Figures As of 12 November (DSWD ) 1.5 M 262,600 48,000 38,000 100,000 19.8M population in severely people affected and in people displaced and in houses damaged people targeted for required funding (US$) affected areas need of assistance recognized evacuation and destroyed shelter/CCCM assistance (1B Philippine Peso) centres SITUATION OVERVIEW On the morning of 29 October 2019, an earthquake of magnitude-6.6 landslides and damaged buildings, the entire population of eight of the response, by aligning humanitarian assistance with long-term at a depth of seven kilometres struck an area 25 kilometres southeast barangays in Makilala had to be evacuated and moved to evacuation development through a Government-led process, and building the of the municipality of Tulunan in North Cotabato province, with another sites after the third earthquake. resilience of the most vulnerable people in the affected areas. magnitude-6.5 earthquake occurring in the same vicinity on 31 October The Consolidated Assessment Report by the Mindanao Humanitarian at a shallow depth of two kilometres. Both earthquakes were tectonic Team (MHT) identified acute needs in the areas of emergency shelter, FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS in origin, with each event followed by many small to strong aftershocks. camp coordination and camp management (CCCM), water, sanitation These two earthquakes were preceded by an earlier magnitude-6.3 Financial resources amounting to an estimated US$19.8 million is and hygiene (WASH) and emergency education.