What the Sarasota County Civic School Building Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 UCF BASEBALL GAME NOTES 11 Conference Championships | 13 NCAA Regional Appearances | 106 MLB Draft Picks GAME INFORMATION Date: Feb

WAKE THE GIANT 2020 UCF BASEBALL GAME NOTES 11 Conference Championships | 13 NCAA Regional Appearances | 106 MLB Draft Picks GAME INFORMATION Date: Feb. 21 | Feb. 22 | Fe. 23 GAME 5-7 Time: 4 p.m. | 3 p.m. | 2 p.m. (ET) Site: Auburn, Ala. Stadium: Plainsman Park Watch: ESPN+ Live Stats: sidearmstats.com/auburn/baseball 2020 SCHEDULE february 14 siena W, 2-1 15 siena W, 11-4 UCF AUBURN 15 siena W, 9-1 KNIGHTS TIGERS 16 siena W, 10-2 RECORD: 4-1, 0-0 RECORD: 5-0, 0-0 18 stetson L, 6-5 CONFERENCE: The American CONFERENCE: Southeastern Conference 21 #8 auburn 4 pm HEAD COACH: Greg Lovelady, Miami ‘01 HEAD COACH: Butch Thompson, Birmingham Southern ‘92 22 #8 auburn 3 pm CAREER RECORD: 239-122 CAREER RECORD: 185-131 23 #8 auburn 2 pm SCHOOL RECORD: 115-66 SCHOOL RECORD: 146-110 25 bethune-cookman 6 pm 28 cal state northridge 6 pm KNIGHT NOTES 29 cal state northridge dh leading off • The Knights won four straight for the 12th time in program history after sweeping Siena on Opening Weekend. march • The opening series sweep of Siena is the third four-game sweep in UCF baseball history. 1 cal state northridge 1 pm • The Black and Gold have outscored their opponents 35-14 through five games this season. 3 jacksonville 6 pm 6 butler 6 pm ranked opposition 7 butler 6 pm • Auburn will be the first ranked opponent the Knights will face in 2020. 8 butler 1 pm • UCF is 22-26 against ranked opposition under head coach Greg Lovelady and went 5-5 against Top 25 11 #7 miami 6 pm opponents in 2019. -

ANNUAL REPORT Mote’S 2019 Annual Report Presents Accomplishments and Finances for the 2019 Fiscal Year, from Oct

2 019 ANNUAL REPORT Mote’s 2019 Annual Report presents accomplishments and finances for the 2019 fiscal year, from Oct. 1, 2018 – Sept. 30, 2019. MOTE’S MISSION The advancement of marine and environmental sciences through scientific research, education and public outreach, leading to new discoveries, revitalization and sustainability of our oceans and greater public understanding of our marine resources. 1 FROM THE CHAIRMAN It is both thrilling and humbling to step Think about the impact Mote will have when we into my role as Chairman as we close increase the number of participants served by our out this successful decade guided by structured education programs from 35,000 today to Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium’s 60,000 by 2030. 2020 Vision & Strategic Plan and pursue Mote’s vision for the next decade, Beyond 2020 we will expand research infrastructure unanimously endorsed by our Board of and accessibility to support global leadership in Trustees and aptly titled “Beyond 2020.” addressing grand challenges facing oceans and coastal ecosystems. Beyond 2020 we will significantly increase our ability to conduct world- Picture the future when Mote will cut the ribbon on a class research in order to expand science-based 110,000-square-foot, state-of-the-art Science Education conservation, sustainable use, and environmental Aquarium and evolve our City Island research health of marine and coastal biodiversity, habitats campus into a world-class International Marine and resources. Science, Technology & Innovation Park by adding or renovating 60,000 square feet by 2030. Envision the change Mote can create when we double down on our funding for annual research operations, Today, however, we proudly look back on a year expanding from $14 million per year today to roughly that closed out an exciting decade for Mote Marine $27 million by 2030. -

From 1955-1961, One of the Most Remarkable Community Civic School

UC Irvine Journal for Learning through the Arts Title Can Architects Help Transform Public Education? What the Sarasota County Civic School Building Program (1955-1960) Teaches Us Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1479d3wp Journal Journal for Learning through the Arts, 9(1) Author Paley, Nicholas B. Publication Date 2013 DOI 10.21977/D9912643 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Can Architects Help Transform Public Education? What the Sarasota County School Building Program (1955-1960) Teaches Us Author: Nicholas Paley Graduate School of Education George Washington University Washington, DC 20052 [email protected] Word Count: 10,270 Abstract: The Sarasota County School Building Program (1955-1960) is revisited through a detailed examination of how architects and educators collaborated to design an innovative group of public schools that provided opportunities for the transformation of learning space. This multi-dimensioned examination is grounded in a historical contextualization of the school building program, in visual and discursive archival analysis related to three of the schools considered especially notable, and in the integration of contemporary voices of some of the teachers, students, and educational employees who worked in these schools. A concluding section discusses four key lessons of this artistic-educational collaboration that might be fruitful for educators to ponder as they seek to create the kinds of community-based learning environments that optimize students’ educational experiences. Introduction From 1955-1960, one of the most remarkable public school building programs in the history of American education took place in Sarasota, Florida. In less than a decade, projects for nine new elementary and secondary schools or additions were commissioned, designed, and constructed --and almost immediately--were being acclaimed as some of the most exciting and varied new schools being built anywhere. -

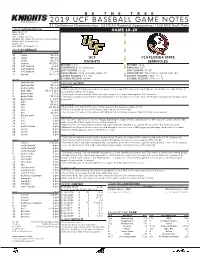

2019 Ucf Baseball Game Notes

BE THE TREE 2019 UCF BASEBALL GAME NOTES 11 Conference Championships | 13 NCAA Regional Appearances | 103 MLB Draft Picks GAME INFORMATION GAME 18-20 Date: March 19 Times: 6 PM Site: Tallahassee, Fla. Stadium: Mike Martin Field at Dick Howser Stadium Watch: ACC Network Extra Listen: N/A Live Stats: UCFKnights.com 2019 SCHEDULE february 6-2 15 siena W, 2-1 16 siena W, 5-1 UCF #14 FLORIDA STATE 17 siena W, 7-1 KNIGHTS SEMINOLES 19 stetson W, 10-2 RECORD: 14-6 RECORD: 14-4 22 #15 auburn L, 4-1 CONFERENCE: The American RANKING: ACC 23 #15 auburn W, 6-1 LAST SEASON: 35-21 LAST SEASON: 43-19 24 #15 auburn L, 13-9 HEAD COACH: Greg Lovelady, Miami ‘01 HEAD COACH: Mike Martin, Florida State ‘66 27 florida W, 12-9 CAREER RECORD: 213-105 CAREER RECORD: 2001-717-4 SCHOOL RECORD: 89-49 SCHOOL RECORD: 2001-717-4 march 8-4 1 jacksonville L, 8-5 KNIGHT NOTES 2 jacksonville W, 3-0 leading off 3 jacksonville W, 6-4 • UCF heads into its final non-conference game before play in The American starts this weekend with a record of 14-6, the 6 ball state W, 9-8 (13) second-best mark in the league. 8 penn state L, 5-2 • The Knights travel to Florida State, looking to snap a five-game slide against the Seminoles. 9 penn state W, 5-3 • The Black and Gold opened the year playing 19 of the first 20 on the road. Now, the Knights will play four straight away 10 penn state L, 11-5 from home. -

A Celebration of Life

A Celebration of Life Henry Adrian “Smokey” Garrett, Jr. April 29, 2021 10:30 am 3201 Windsor Road | Austin tx 78703 | 512.476.3523 | gsaustin.org [ 2 ] The Holy Eucharist Burial of the Dead welcome entrance hymn 361 Amazing Grace About the Liturgy The liturgy for the dead is an Easter liturgy. It finds all its meaning in the resurrection. Because Jesus was raised from the dead, we, too, shall be raised. The liturgy, therefore, is characterized by joy, in the certainty that ‘neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.’ This joy, however, does not make human grief unchristian. The very love we have for each other in Christ brings deep sorrow when we are parted by death. Jesus himself wept at the grave of his friend. So, while we rejoice that one we love has entered into the nearer presence of our Lord, we sorrow in sympathy with those who mourn. opening anthems 10:00 am [ 3 ] Officiant I am Resurrection and I am Life, says the Lord. Whoever has faith in me shall have life, even though he die. And everyone who has life, and has committed himself to me in faith, shall not die for ever. As for me, I know that my Redeemer lives and that at the last he will stand upon the earth. After my awaking, he will raise me up; and in my body I shall see God. -

List of Applicant's Expert Witness Resumes

List of Applicant's Expert Witness Resumes Mark R. Stephens, P.G., P.E The Colinas Group, Inc. Jeffrey A. Straw GeoSonics, Inc. Christopher C. Hatton, P.E. KimleyHom Darren L. Stowe, AICP Environmental Consulting &Technology Inc. Kelly M. Love, MCP Clearview Land Design, PL Michael A. McElveen, MAI, CCUIM, CRE Urban Economics, Inc. Henry J. Fishkind, Ph.D. Fishkind & Associates, Inc. Lee M. Walton Flatwoods Consulting Group Lee Hutchinson, RP A Archaeological Consultants, Inc. Dr. Christopher M. Teaf Toxicologist, Florida State University David L. Teasdale, P.E. HAAG Engineering MARK R. STEPHENS, P. G., P. E. THE COLINAS GROUP, INC 2031 EAST EDGEWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 5 LAKELAND, FLORIDA 33803 TITLE: President I Principal Consultant EDUCATION: M.S., 1974 Geology/Water Resources, Iowa State University B.S., 1972 Geology, Iowa State University PROFESSIONAL LICENSES: Professional Engineer - Florida Professional Geologist - Florida Professional Geologist - Kentucky PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: 43 Years SELECTED EXPERIENCE: CIVIL ENGINEERING • Environmental Resource Permitting and stormwater management design for numerous sand mines, limestone quarries, and industrial facilities in Florida. • Mine design and permitting for limestone quarries in Sumter, Alachua, Collier, Marion, Hernando, Palm Beach and Lee Counties and sand mines in Polk, Lake, and Glades Counties, Florida. • Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasures Plans (SPCC Plans) for numerous sand mines, limestone quarries, and industrial facilities in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina. • Best Management Practices Plans for numerous sand mines, limestone quarries, and industrial facilities in Florida • Design of environmental monitoring and management programs for numerous sand mines and limestone quarries in Florida. • Stormwatermanagement system design and permitting for industrial facilities including office buildings, paving projects, sand mines and limestone quarries in Florida. -

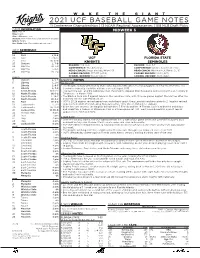

2021 Ucf Baseball Game Notes

WAKE THE GIANT 2021 UCF BASEBALL GAME NOTES 11 Conference Championships | 13 NCAA Regional Appearances | 108 MLB Draft Picks GAME INFORMATION Date: Mar 24 MIDWEEK 5 Time: 6 pm Site: Tallahassee, Fla. Stadium: Mike Martin Field at Dick Howser Stadium Watch: ACCN Live Stats: http://fsu.statbroadcast.com/ 2021 SCHEDULE february 19 FAU L,12-6 20 FAU L, 20-15 UCF FLORIDA STATE 21 FAU W, 15-6 KNIGHTS SEMINOLES 23 Stetson L, 7-0 7-9, 0-0 10-6, 7-5 26 Ole Miss W, 3-2 RECORD: RECORD: The American Atlantic Coast Conference 27 Ole Miss L 6-5 CONFERENCE: CONFERENCE: Greg Lovelady, Miami ‘01 Mike Martin Jr., Florida St., ‘95 28 Ole Miss W, 7-2 HEAD COACH: HEAD COACH: CAREER RECORD: 257-133 (.659) CAREER RECORD: 22-11 (.667) 133-77 (.633) 22-11 (.667) march SCHOOL RECORD: SCHOOL RECORD: 3 Stetson L, 6-5 KNIGHT NOTES 5 Liberty L, 2-1 leading off Liberty L, 8-3 • The Knights history with Florida State dates back to 1985 when the two programs met for the first time. The 7 Liberty L, 3-2 Seminoles currently leads the all-time series sitting at 7-35 10 North Florida W, 10-0 • The last time UCF and the Seminoles met, the Knights stopped their five-game losing skid with a 9-7 victory in 12 North Florida W, 6-2 Tallahassee in March 2019 13 North Florida L, 14-7 • The Black & Gold is 6-5 against teams in the Sunshine State, with 10 more games against Florida foes after the 14 North Florida W, 3-2 midweek contest with Florida State 16 FAU W, 8-3 • UCF is 27-28 against ranked opposition under head coach Greg Lovelady and are currently 2-1 against ranked 19 Jacksonville L, 2-1 opponents in 2021 after defeating then-ranked No. -

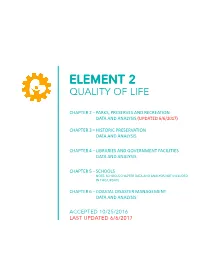

Element 2 Element 2

ELEMENTELEMENT 2 QUALITY OF LIFE CHAPTER 2 – PARKS, PRESERVES AND RECREATION DATA AND ANALYSIS (UPDATED 6/6/2017) CHAPTER 3 – HISTORIC PRESERVATION DATA AND ANALYSIS CHAPTER 4 – LIBRARIES AND GOVERNMENT FACILITIES DATA AND ANALYSIS CHAPTER 5 – SCHOOLS NOTE: SCHOOLS CHAPTER DATA AND ANALYSIS NOT INCLUDED IN THIS UPDATE CHAPTER 6 – COASTAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT DATA AND ANALYSIS ACCEPTED 10/25/2016 LAST UPDATED 6/6/2017 quality of life element | data and analysis 10/25/2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES, MAPS AND FIGURES V2-178 CHAPTER 2 – PARKS, PRESERVES AND RECREATION DATA AND ANALYSIS BACKGROUND V2- 183 V2-184 EXISTING CONDITIONS CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM SUBSYSTEMS INVENTORY OF EXISTING COUNTY-OWNED AND OPERATED PARKS INTERLOCAL AGREEMENTS ADDITIONAL RECREATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES ANALYSIS NEEDS ASSESSMENT V2-189 LEVELS OF SERVICE PARK PLANNING, ACQUISITION AND V2-213 DEVELOPMENT FOCUS AREAS V2-214 CONCLUSION V2-215 CHAPTER 2 – PARKS, PRESERVES AND RECREATION V2-213 MAPS AND FIGURES CHAPTER 3 – HISTORIC PRESERVATION DATA AND ANALYSIS EVALUATION OF HISTORIC RESOURCES V2-222 V2-176 sarasota county comprehensive plan | volume 2: data and analysis quality of life introduction | data and analysis 10/25/2016 PROTECTION OF HISTORIC RESOURCES V2-224 STUDIES & SURVEYS V2-229 SITE LISTS V2-231 ARCHIVAL ACTIVITIES V2-232 CHAPTER 3 – HISTORIC PRESERVATION V2-235 MAPS CHAPTER 3 – HISTORIC PRESERVATION APPENDIX SECTION 1: PRESERVATION LAWS V2-242 SECTION 2: NATIONAL REGISTER PROGRAM V2-250 SECTION 3: PRIVATE ORGANIZATIONS V2-251 SECTION 4: BIBLIOGRAPHY -

Upcoming Probables (All Times CT) 5/26 @ Gwinnett Stripers 6:05 P.M

Tuesday, May 25th 6:05 p.m CT Memphis Redbirds (8-10) at Gwinnett Stripers (9-9) Game 1 of 6 Coolray Field / Gwinnett, GA Game #19 of 120 / Road Game #7 of 60 RHP Angel Rondón (0-2, 7.98 ERA) vs RHP Kyle Wright (0-2, 6.75 ERA) First Pitch App: Evan Stockton & Justin Gallanty Last Game – 5/23/21 Bird Bites Memphis vs. Gwinnett ‘21 Last Time Out: The Redbirds dropped the final game of their series against LOU 8 10 0 the Louisville Bats by a score of 8-3. The loss snapped the ‘Birds four-game 12 Home, 12 Away (24 Total) winning streak. Louisville jumped out to an early 4-0 lead in the game and 5/25 A – MEM 3 5 1 5/26 A – never trailed. Memphis scored all three of its runs on the afternoon on solo 5/27 A – home runs. Lars Nootbaar went deep twice and Kramer Robertson 5/28 A – WP: Tony Santillan (1-1) launched his second home run of the season. Even with the loss, the Redbirds 5/29 A – took four of the six games in the series against Louisville. 5/30 A – - 5.1 IP, 5 H, 3 ER, 2 BB, 3 K 6/8 H – 6/9 H – LP: Matthew Liberatore (0-3) Today’s Starter: Angel Rondón will make his fourth appearance and third 6/10 H – start of the year for the Redbirds today. Rondón is coming off his best outing of 6/11 H – -4.0 IP, 5 H, 4 ER, 1 BB, 5 K the young season. -

UNIVERSITY of SOUTH FLORIDA: the First Fifty Years, 1956-2006

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Western Libraries Faculty and Staff ubP lications Western Libraries and the Learning Commons 1-1-2006 University of South Florida: The irsF t Fifty Years, 1956-2006 Mark I. Greenberg University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/library_facpubs Part of the Higher Education Commons, Higher Education Administration Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Greenberg, Mark I., "University of South Florida: The irF st Fifty Years, 1956-2006" (2006). Western Libraries Faculty and Staff Publications. 43. https://cedar.wwu.edu/library_facpubs/43 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Libraries and the Learning Commons at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western Libraries Faculty and Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA: The First Fifty Years, 1956-2006 By Mark I. Greenberg Lead Research by Andrew T. Huse Design by Marilyn Keltz Stephens PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH FLORIDA Tampa, Florida, 2006 Acknowledgements This project began more than three and a half years ago during a meeting with USF President Judy Genshaft. I came prepared for our discussion with several issues for her consideration. She had a topic she wanted to discuss with me. As it turned out, we both wanted to talk about celebrating the university’s fiftieth anniversary with a commemorative book. As our conversation unfolded, she commissioned me to write a celebratory coffee table-style history. -

Upcoming Probables (All Times CT) 5/29 @ Gwinnett Stripers 5:05 P.M

Friday, May 28th 6:05 p.m CT Memphis Redbirds (8-13) at Gwinnett Stripers (12-9) Game 4 of 6 Coolray Field / Lawrenceville, GA Game #22 of 120 / Road Game #10 of 60 RHP Tommy Parsons (0-0, 3.05 ERA) vs RHP Bryse Wilson (1-0, 3.27 ERA) First Pitch App: Evan Stockton & Justin Gallanty Last Game – 5/27/21 Bird Bites Memphis vs. Gwinnett ‘21 Last Time Out: The Redbirds had a difficult night in Gwinnett, dropping a 14-2 MEM 2 5 0 contest on Thursday night. With the win, the Stripers have now taken the first three 12 Home, 12 Away (24 Total) games of the series at Coolray Field. Gwinnett got off to a hot start, scoring eight 5/25 A – L, 2-1 GWN 14 18 0 runs in the second inning and five runs in the fifth. Alex Jackson had a huge 5/26 A – L, 11-5 5/27 A – L, 14-2 game, hitting three home runs and driving in seven runs. The Redbirds got their two 5/28 A – WP: Kyle Muller (1-1) runs on solo home runs from José Rondón and Matt Szczur. 5/29 A – 5/30 A – - 5.0 IP, 3 H, ER, 0 BB, 8 K Today’s Starter: Tommy Parsons will make his fifth appearance and third start of 6/8 H – the season for the Redbirds tonight. Parsons is coming off an outstanding start last 6/9 H – LP: Zack Thompson (0-2) week against Louisville in which he pitched seven strong innings, allowing just two 6/10 H – runs. -

Upcoming Probables (All Times CT) 5/14 @ Nashville Sounds 6:35 P.M LHP Bernardo Flores, Jr

Thursday, May 13th 6:35 p.m CT Memphis Redbirds (2-6) at Nashville Sounds (4-3) Game 3 of 6 First Horizon Park / Nashville, TN Game #9 of 120 / Road Game #3 of 60 RHP Angel Rondón (0-1, 12.46 ERA) vs LHP Blaine Hardy (0-0, 2.70 ERA) MiLB First Pitch App: Evan Stockton & Justin Gallanty Last Game – 5/12/21 Bird Bites Memphis vs. Sounds ‘21 Last Time Out: The Redbirds’ late comeback attempt fell short in MEM 6 6 0 Nashville on Wednesday night, with the contest ending in a 9-6 6 Home, 12 Away (18 Total) 5/11 A – W, 18-6 Sounds’ victory. Memphis got on the board in the second inning on an NAS 9 12 2 5/12 A – L, 9-6 RBI single from Scott Hurst, which tied the game at 1-1. Nashville 5/13 A – opened up a big lead in the third, scoring four times. The ‘Birds got a WP: Miguel Sanchez (1-0) 5/14 A – run in the fifth when John Nogowski singled in a run, but Nashville -2.1 IP, 1 H, 1 R, 0 ER, 2 BB, 2 K 5/15 A – was able to pull away with three runs in the seventh and one more in 5/16 A – LP: Matthew Liberatore (0-2) the eighth. Max Moroff and Matt Szczur each homered in the ninth 8/17 H – inning as the Redbirds fought back, but Nashville was able to close - 6.0 IP, 7 H, 5 ER, 1 BB, 4 K 8/18 H – out a 9-6 win.