From 1955-1961, One of the Most Remarkable Community Civic School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 UCF BASEBALL GAME NOTES 11 Conference Championships | 13 NCAA Regional Appearances | 106 MLB Draft Picks GAME INFORMATION Date: Feb

WAKE THE GIANT 2020 UCF BASEBALL GAME NOTES 11 Conference Championships | 13 NCAA Regional Appearances | 106 MLB Draft Picks GAME INFORMATION Date: Feb. 21 | Feb. 22 | Fe. 23 GAME 5-7 Time: 4 p.m. | 3 p.m. | 2 p.m. (ET) Site: Auburn, Ala. Stadium: Plainsman Park Watch: ESPN+ Live Stats: sidearmstats.com/auburn/baseball 2020 SCHEDULE february 14 siena W, 2-1 15 siena W, 11-4 UCF AUBURN 15 siena W, 9-1 KNIGHTS TIGERS 16 siena W, 10-2 RECORD: 4-1, 0-0 RECORD: 5-0, 0-0 18 stetson L, 6-5 CONFERENCE: The American CONFERENCE: Southeastern Conference 21 #8 auburn 4 pm HEAD COACH: Greg Lovelady, Miami ‘01 HEAD COACH: Butch Thompson, Birmingham Southern ‘92 22 #8 auburn 3 pm CAREER RECORD: 239-122 CAREER RECORD: 185-131 23 #8 auburn 2 pm SCHOOL RECORD: 115-66 SCHOOL RECORD: 146-110 25 bethune-cookman 6 pm 28 cal state northridge 6 pm KNIGHT NOTES 29 cal state northridge dh leading off • The Knights won four straight for the 12th time in program history after sweeping Siena on Opening Weekend. march • The opening series sweep of Siena is the third four-game sweep in UCF baseball history. 1 cal state northridge 1 pm • The Black and Gold have outscored their opponents 35-14 through five games this season. 3 jacksonville 6 pm 6 butler 6 pm ranked opposition 7 butler 6 pm • Auburn will be the first ranked opponent the Knights will face in 2020. 8 butler 1 pm • UCF is 22-26 against ranked opposition under head coach Greg Lovelady and went 5-5 against Top 25 11 #7 miami 6 pm opponents in 2019. -

ANNUAL REPORT Mote’S 2019 Annual Report Presents Accomplishments and Finances for the 2019 Fiscal Year, from Oct

2 019 ANNUAL REPORT Mote’s 2019 Annual Report presents accomplishments and finances for the 2019 fiscal year, from Oct. 1, 2018 – Sept. 30, 2019. MOTE’S MISSION The advancement of marine and environmental sciences through scientific research, education and public outreach, leading to new discoveries, revitalization and sustainability of our oceans and greater public understanding of our marine resources. 1 FROM THE CHAIRMAN It is both thrilling and humbling to step Think about the impact Mote will have when we into my role as Chairman as we close increase the number of participants served by our out this successful decade guided by structured education programs from 35,000 today to Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium’s 60,000 by 2030. 2020 Vision & Strategic Plan and pursue Mote’s vision for the next decade, Beyond 2020 we will expand research infrastructure unanimously endorsed by our Board of and accessibility to support global leadership in Trustees and aptly titled “Beyond 2020.” addressing grand challenges facing oceans and coastal ecosystems. Beyond 2020 we will significantly increase our ability to conduct world- Picture the future when Mote will cut the ribbon on a class research in order to expand science-based 110,000-square-foot, state-of-the-art Science Education conservation, sustainable use, and environmental Aquarium and evolve our City Island research health of marine and coastal biodiversity, habitats campus into a world-class International Marine and resources. Science, Technology & Innovation Park by adding or renovating 60,000 square feet by 2030. Envision the change Mote can create when we double down on our funding for annual research operations, Today, however, we proudly look back on a year expanding from $14 million per year today to roughly that closed out an exciting decade for Mote Marine $27 million by 2030. -

Toward a Framework for Preserving Mid-Century Modern Resources: an Examination of Public Perceptions of the Sarasota School of Architecture

TOWARD A FRAMEWORK FOR PRESERVING MID-CENTURY MODERN RESOURCES: AN EXAMINATION OF PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS OF THE SARASOTA SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE By NORA L. GALLAGHER A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 ©2011 Nora Louise Gallagher 2 To my family 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First I would like to thank my committee chair, Morris Hylton, III who showed much patience and dedication to the project. I would also like to thank Sara Katherine Williams who came onto my committee last minute, but with no less dedication. I would also like to thank all of those who took the time out of their day at the beach or lunch schedule to answer my questions. Special thanks also goes Blair Mullins who not only helped with interviewing, but inspired motivation in me. Finally, I would like to thank my parents, Phil and Linda Gallagher who used to force me to work on house projects and repairs – without this I would not have an appreciation for what makes a building important, the memories which are made there. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 4 LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................ 7 LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 8 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................. -

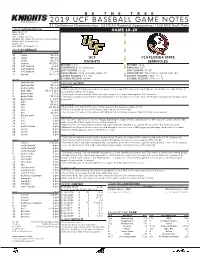

2019 Ucf Baseball Game Notes

BE THE TREE 2019 UCF BASEBALL GAME NOTES 11 Conference Championships | 13 NCAA Regional Appearances | 103 MLB Draft Picks GAME INFORMATION GAME 18-20 Date: March 19 Times: 6 PM Site: Tallahassee, Fla. Stadium: Mike Martin Field at Dick Howser Stadium Watch: ACC Network Extra Listen: N/A Live Stats: UCFKnights.com 2019 SCHEDULE february 6-2 15 siena W, 2-1 16 siena W, 5-1 UCF #14 FLORIDA STATE 17 siena W, 7-1 KNIGHTS SEMINOLES 19 stetson W, 10-2 RECORD: 14-6 RECORD: 14-4 22 #15 auburn L, 4-1 CONFERENCE: The American RANKING: ACC 23 #15 auburn W, 6-1 LAST SEASON: 35-21 LAST SEASON: 43-19 24 #15 auburn L, 13-9 HEAD COACH: Greg Lovelady, Miami ‘01 HEAD COACH: Mike Martin, Florida State ‘66 27 florida W, 12-9 CAREER RECORD: 213-105 CAREER RECORD: 2001-717-4 SCHOOL RECORD: 89-49 SCHOOL RECORD: 2001-717-4 march 8-4 1 jacksonville L, 8-5 KNIGHT NOTES 2 jacksonville W, 3-0 leading off 3 jacksonville W, 6-4 • UCF heads into its final non-conference game before play in The American starts this weekend with a record of 14-6, the 6 ball state W, 9-8 (13) second-best mark in the league. 8 penn state L, 5-2 • The Knights travel to Florida State, looking to snap a five-game slide against the Seminoles. 9 penn state W, 5-3 • The Black and Gold opened the year playing 19 of the first 20 on the road. Now, the Knights will play four straight away 10 penn state L, 11-5 from home. -

A Celebration of Life

A Celebration of Life Henry Adrian “Smokey” Garrett, Jr. April 29, 2021 10:30 am 3201 Windsor Road | Austin tx 78703 | 512.476.3523 | gsaustin.org [ 2 ] The Holy Eucharist Burial of the Dead welcome entrance hymn 361 Amazing Grace About the Liturgy The liturgy for the dead is an Easter liturgy. It finds all its meaning in the resurrection. Because Jesus was raised from the dead, we, too, shall be raised. The liturgy, therefore, is characterized by joy, in the certainty that ‘neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.’ This joy, however, does not make human grief unchristian. The very love we have for each other in Christ brings deep sorrow when we are parted by death. Jesus himself wept at the grave of his friend. So, while we rejoice that one we love has entered into the nearer presence of our Lord, we sorrow in sympathy with those who mourn. opening anthems 10:00 am [ 3 ] Officiant I am Resurrection and I am Life, says the Lord. Whoever has faith in me shall have life, even though he die. And everyone who has life, and has committed himself to me in faith, shall not die for ever. As for me, I know that my Redeemer lives and that at the last he will stand upon the earth. After my awaking, he will raise me up; and in my body I shall see God. -

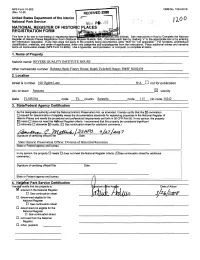

3/24,/Loffr D Determined Eligible for the National Register D See Continuation Sheet

NPSForm 10-900 OMBNo. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTOR REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determ districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property___________________________________________________ historic name REVERE QUALITY INSTITUTE HOUSE_________________________________ other names/site number Roberta Healv Finnev House. Ralph Twitchell House: FMSF SO02439_______________ 2. Location street & number IQOOgdenLane N/A D not for publication city or town Sarasota vicinity state FLORIDA code FL county Sarasota .code 115 zio code 34242 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this E3 nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ^ meets D does not meet the Naftional Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally D statewide 13 locally. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

WHAT IS OCALA BLOCK? By MAANVI CHAWLA A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2018 © 2018 Maanvi Chawla To my parents, Neeta and Anil Chawla, and to the quirky, enchanting State of Florida. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the people of Florida for being so warm, receptive and enthusiastic as I made my way through the research for this thesis. I specially want to thank my Chair and Advisor, Marty Hylton, for introducing me to this topic as and when I expressed a desire to research on building materials. I would like to thank my Committee’s Special Member, Dr. Matthew Smith, for always being supportive, answering all my queries and for opening the doors of the Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Florida for me to conduct research. Special thanks to Dr. Norman Weiss, who gladly offered his expertise and valuable support especially through the tough initial phases of this thesis. I am thankful to Integrated Conservation Resources, Inc. for their generosity in letting me access their facilities for my research. Lastly, I would like to thank the helpful experts from the fields of architecture, history and materials conservation for their support and the innumerable resource people who came forward to engage on trivia and conversation surrounding Ocala block in Florida. I would like to acknowledge the immense amount of support and love given to me by my parents, Neeta and Anil Chawla, and by my sister, Meetali Bedi and her family. -

FUN in the SUNSHINE CITY Tour 1 • April 10, 2014

FUN IN THE SUNSHINE CITY Tour 1 • April 10, 2014 The beginning porTion OF THIS TOUR follows Central Avenue from downtown through western St.Petersburg and Pasadena to the barrier island communities of Treasure Island and St. Pete Beach. From St. Pete Beach, we will cross the Sunshine Skyway Bridge to Bradenton and the ultimate destination for the trip, Sarasota. St. Petersburg to Sarasota Tour 1 • April 10, 2014 • 9 Am – 6 pm Presented by the Society for Commercial Archeology with generous support from the Historic Preservation Division of the City of St. Petersburg, Kilby Creative, and Archaeological Consultants, Inc St. Petersburg We will start this tour in downtown The current BANDSHELL, designed St. Petersburg at the PENNSYLVANIA by architect William “Bill” Harvard in HOTEL, now a Courtyard Marriott 1952, won an Award for Excellence in Hotel which is serving as the confer- Architecture from the national American ence hotel. Situated on the corner of Institute of Architects. He later designed 4th Street North and 3rd Avenue, the the inverted pyramid pier. In the early Pennsylvania was built by Harry C. years, shuffleboard, roque, chess, and Case in 1925. In the next few blocks, dominoes attracted tourists to the park. we will pass the MIRROR LAKE When clubs formed and attempted to CARNEGIE LIBRARY, completed in limit the park’s use to their members, 1915 and situated on MIRROR LAKE, the heirs of John Williams sued as it was the source of the City’s early water dedicated as a public park for all citizens. supply and St. Petersburg’s WPA funded This led to the creation of the Mirror 1937 CITY HALL, the location for the Lake Recreation Complex. -

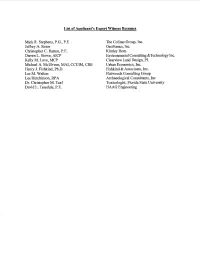

List of Applicant's Expert Witness Resumes

List of Applicant's Expert Witness Resumes Mark R. Stephens, P.G., P.E The Colinas Group, Inc. Jeffrey A. Straw GeoSonics, Inc. Christopher C. Hatton, P.E. KimleyHom Darren L. Stowe, AICP Environmental Consulting &Technology Inc. Kelly M. Love, MCP Clearview Land Design, PL Michael A. McElveen, MAI, CCUIM, CRE Urban Economics, Inc. Henry J. Fishkind, Ph.D. Fishkind & Associates, Inc. Lee M. Walton Flatwoods Consulting Group Lee Hutchinson, RP A Archaeological Consultants, Inc. Dr. Christopher M. Teaf Toxicologist, Florida State University David L. Teasdale, P.E. HAAG Engineering MARK R. STEPHENS, P. G., P. E. THE COLINAS GROUP, INC 2031 EAST EDGEWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 5 LAKELAND, FLORIDA 33803 TITLE: President I Principal Consultant EDUCATION: M.S., 1974 Geology/Water Resources, Iowa State University B.S., 1972 Geology, Iowa State University PROFESSIONAL LICENSES: Professional Engineer - Florida Professional Geologist - Florida Professional Geologist - Kentucky PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: 43 Years SELECTED EXPERIENCE: CIVIL ENGINEERING • Environmental Resource Permitting and stormwater management design for numerous sand mines, limestone quarries, and industrial facilities in Florida. • Mine design and permitting for limestone quarries in Sumter, Alachua, Collier, Marion, Hernando, Palm Beach and Lee Counties and sand mines in Polk, Lake, and Glades Counties, Florida. • Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasures Plans (SPCC Plans) for numerous sand mines, limestone quarries, and industrial facilities in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina. • Best Management Practices Plans for numerous sand mines, limestone quarries, and industrial facilities in Florida • Design of environmental monitoring and management programs for numerous sand mines and limestone quarries in Florida. • Stormwatermanagement system design and permitting for industrial facilities including office buildings, paving projects, sand mines and limestone quarries in Florida. -

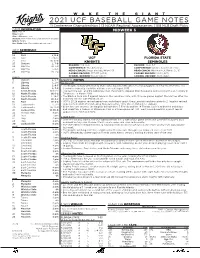

2021 Ucf Baseball Game Notes

WAKE THE GIANT 2021 UCF BASEBALL GAME NOTES 11 Conference Championships | 13 NCAA Regional Appearances | 108 MLB Draft Picks GAME INFORMATION Date: Mar 24 MIDWEEK 5 Time: 6 pm Site: Tallahassee, Fla. Stadium: Mike Martin Field at Dick Howser Stadium Watch: ACCN Live Stats: http://fsu.statbroadcast.com/ 2021 SCHEDULE february 19 FAU L,12-6 20 FAU L, 20-15 UCF FLORIDA STATE 21 FAU W, 15-6 KNIGHTS SEMINOLES 23 Stetson L, 7-0 7-9, 0-0 10-6, 7-5 26 Ole Miss W, 3-2 RECORD: RECORD: The American Atlantic Coast Conference 27 Ole Miss L 6-5 CONFERENCE: CONFERENCE: Greg Lovelady, Miami ‘01 Mike Martin Jr., Florida St., ‘95 28 Ole Miss W, 7-2 HEAD COACH: HEAD COACH: CAREER RECORD: 257-133 (.659) CAREER RECORD: 22-11 (.667) 133-77 (.633) 22-11 (.667) march SCHOOL RECORD: SCHOOL RECORD: 3 Stetson L, 6-5 KNIGHT NOTES 5 Liberty L, 2-1 leading off Liberty L, 8-3 • The Knights history with Florida State dates back to 1985 when the two programs met for the first time. The 7 Liberty L, 3-2 Seminoles currently leads the all-time series sitting at 7-35 10 North Florida W, 10-0 • The last time UCF and the Seminoles met, the Knights stopped their five-game losing skid with a 9-7 victory in 12 North Florida W, 6-2 Tallahassee in March 2019 13 North Florida L, 14-7 • The Black & Gold is 6-5 against teams in the Sunshine State, with 10 more games against Florida foes after the 14 North Florida W, 3-2 midweek contest with Florida State 16 FAU W, 8-3 • UCF is 27-28 against ranked opposition under head coach Greg Lovelady and are currently 2-1 against ranked 19 Jacksonville L, 2-1 opponents in 2021 after defeating then-ranked No. -

Element 2 Element 2

ELEMENTELEMENT 2 QUALITY OF LIFE CHAPTER 2 – PARKS, PRESERVES AND RECREATION DATA AND ANALYSIS (UPDATED 6/6/2017) CHAPTER 3 – HISTORIC PRESERVATION DATA AND ANALYSIS CHAPTER 4 – LIBRARIES AND GOVERNMENT FACILITIES DATA AND ANALYSIS CHAPTER 5 – SCHOOLS NOTE: SCHOOLS CHAPTER DATA AND ANALYSIS NOT INCLUDED IN THIS UPDATE CHAPTER 6 – COASTAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT DATA AND ANALYSIS ACCEPTED 10/25/2016 LAST UPDATED 6/6/2017 quality of life element | data and analysis 10/25/2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES, MAPS AND FIGURES V2-178 CHAPTER 2 – PARKS, PRESERVES AND RECREATION DATA AND ANALYSIS BACKGROUND V2- 183 V2-184 EXISTING CONDITIONS CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM SUBSYSTEMS INVENTORY OF EXISTING COUNTY-OWNED AND OPERATED PARKS INTERLOCAL AGREEMENTS ADDITIONAL RECREATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES ANALYSIS NEEDS ASSESSMENT V2-189 LEVELS OF SERVICE PARK PLANNING, ACQUISITION AND V2-213 DEVELOPMENT FOCUS AREAS V2-214 CONCLUSION V2-215 CHAPTER 2 – PARKS, PRESERVES AND RECREATION V2-213 MAPS AND FIGURES CHAPTER 3 – HISTORIC PRESERVATION DATA AND ANALYSIS EVALUATION OF HISTORIC RESOURCES V2-222 V2-176 sarasota county comprehensive plan | volume 2: data and analysis quality of life introduction | data and analysis 10/25/2016 PROTECTION OF HISTORIC RESOURCES V2-224 STUDIES & SURVEYS V2-229 SITE LISTS V2-231 ARCHIVAL ACTIVITIES V2-232 CHAPTER 3 – HISTORIC PRESERVATION V2-235 MAPS CHAPTER 3 – HISTORIC PRESERVATION APPENDIX SECTION 1: PRESERVATION LAWS V2-242 SECTION 2: NATIONAL REGISTER PROGRAM V2-250 SECTION 3: PRIVATE ORGANIZATIONS V2-251 SECTION 4: BIBLIOGRAPHY -

MOD 2015 Program

November – 8, 2015 SarasotaMOD Weekend 2015 At-a-Glance Friday, Nov 6, 2015 Saturday, Nov 7, 2015 Opening Day Tour Day SarasotaMOD.com Presentation 1: Breakfast at The Francis Twitchell and Rudolph, $40 Included with Presentation 3 2 to 3:15 pm, Sainer Auditorium, New College 8 to 9 am, 1289 N. Palm Avenue Paul Rudolph’s first job in Sarasota was with architect Ralph Start the day with a delicious Continental Breakfast Buffet... Twitchell. Christopher Wilson, professor at Ringling College of danishes, muffins, croissants plus fresh fruits, honey yogurt Art + Design, will lead the panel in a discussion of Twitchell’s with toasted coconut cashew granola, fresh juices and coffee work and the complex relationship between Twitchell and and tea. Rudolph. The panel includes architect John Howey, one of Twitchell’s last partners Richard Allen, architect and author Joe Presentation 3: King and Twitchell’s granddaughter Julie Hutchins-Wilson. Rudolph’s Sarasota Houses, $50 Includes Breakfast Presentation 2: 9 to 10:30 am, The Francis, 1289 N. Palm Avenue The Walker Guest House and the Replica Co-authors of the beautiful, newly reprinted book, “Paul $40 Rudolph: The Florida Houses,” Christopher Domin and Joe 3:30 to 4:45 pm, Sainer Auditorium, New College King will present the innovative houses Rudolph designed in SAF’s replica of the Walker Guest House is the highlight of the late 1940s and 1950s. This primer on Rudolph’s early MOD this year. Author and architectural critic, Alastair work is the perfect introduction for MOD’s Trolley Tours of Gordon and his panel will explore this remarkable structure, Siesta Key, the Walking Tours of Lido Shores, and the the “spider in the sand” and the “lessons learned” in building Umbrella House.