Hazleton, Gloucestershire, to C.1600 by Christopher Dyer and David Aldred 2009, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PREFACE in 1974 Enid and I Decided to Look for a House of Our Own As I

PREFACE In 1974 Enid and I decided to look for a house of our own as I was due to retire in 1976. Gloucestershire we knew was a nice county in which to live. We had certain connections with it. On our days off we frequently toured the Cotswolds, we were then living in Henley-on-Thames. Added to this, in about 1910 my father considered buying the practice at Northleach and so becoming its local doctor, however, he went to Weobley in Herefordshire. His father, James Strachan Clarke who died in 1976 aged 45 or 46 had been a tenant farmer at Ashwick Grange, Marshfield and apparently the Land Agent of the people living at Ashwick Hall. Unfortunately, the records of ownership of the Hall were destroyed in the Bristol blitz during World War II so I know nothing about them. In the parish church there is a brass plate concerning him. The name is incorrect, he is called James Stephenson Clarke, this was an error on the part of my Aunt Agnes, his eldest daughter. In 1775 a certain John Clarke married Jane Stephenson, she is alleged to be the beauty of the Clarkes (though I would think, judging from the pictures, that my wife Enid, runs her a close second and is probably ahead of her). The name Stephenson became attached to the Clarkes until the present day. After a long search we saw a photograph of our cottage in the premises of Bloss, Tippett and Taylor of Bourton-on-the-Water and in 1976 bought it from Mr. -

How Useful Are Episcopal Ordination Lists As a Source for Medieval English Monastic History?

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. , No. , July . © Cambridge University Press doi:./S How Useful are Episcopal Ordination Lists as a Source for Medieval English Monastic History? by DAVID E. THORNTON Bilkent University, Ankara E-mail: [email protected] This article evaluates ordination lists preserved in bishops’ registers from late medieval England as evidence for the monastic orders, with special reference to religious houses in the diocese of Worcester, from to . By comparing almost , ordination records collected from registers from Worcester and neighbouring dioceses with ‘conven- tual’ lists, it is concluded that over per cent of monks and canons are not named in the extant ordination lists. Over half of these omissions are arguably due to structural gaps in the surviving ordination lists, but other, non-structural factors may also have contributed. ith the dispersal and destruction of the archives of religious houses following their dissolution in the late s, many docu- W ments that would otherwise facilitate the prosopographical study of the monastic orders in late medieval England and Wales have been irre- trievably lost. Surviving sources such as the profession and obituary lists from Christ Church Canterbury and the records of admissions in the BL = British Library, London; Bodl. Lib. = Bodleian Library, Oxford; BRUO = A. B. Emden, A biographical register of the University of Oxford to A.D. , Oxford –; CAP = Collectanea Anglo-Premonstratensia, London ; DKR = Annual report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records, London –; FOR = Faculty Office Register, –, ed. D. S. Chambers, Oxford ; GCL = Gloucester Cathedral Library; LP = J. S. Brewer and others, Letters and papers, foreign and domestic, of the reign of Henry VIII, London –; LPL = Lambeth Palace Library, London; MA = W. -

Painswick to Winchcombe Cycle Route

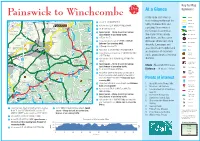

Great Comberton A4184 Elmley Castle B4035 Netherton B4632 B4081 Hinton on the Green Kersoe A38 CHIPPING CAMPDEN A46(T) Aston Somerville Uckinghall Broadway Ashton under Hill Kemerton A438 (T) M50 B4081 Wormington B4479 Laverton B4080 Beckford Blockley Ashchurch B4078 for Tewkesbury Bushley B4079 Great Washbourne Stanton A38 A38 Key to Map A417 TEWKESBURY A438 Alderton Snowshill Day A438 Bourton-on-the-Hill Symbols: B4079 A44 At a Glance M5 Teddington B4632 4 Stanway M50 B4208 Dymock Painswick to WinchcombeA424 Linkend Oxenton Didbrook A435 PH A hilly route from start to A Road Dixton Gretton Cutsdean Hailes B Road Kempley Deerhurst PH finish taking you through the Corse Ford 6 At fork TL SP BRIMPSFIELD. B4213 B4211 B4213 PH Gotherington Minor Road Tredington WINCHCOMBE Farmcote rolling Cotswold hills and Tirley PH 7 At T junctionB4077 TL SP BIRDLIP/CHELTENHAM. Botloe’s Green Apperley 6 7 8 9 10 Condicote Motorway Bishop’s Cleeve PH Several capturing the essence of Temple8 GuitingTR SP CIRENCESTER. Hardwicke 22 Lower Apperley Built-up Area Upleadon Haseld Coombe Hill the Cotswold countryside. Kineton9 Speed aware – Steep descent on narrow B4221 River Severn Orchard Nook PH Roundabouts A417 Gorsley A417 21 lane. Beware of oncoming traffic. The route follows mainly Newent A436 Kilcot A4091 Southam Barton Hartpury Ashleworth Boddington 10 At T junction TL. Lower Swell quiet lanes, and has some Railway Stations B4224 PH Guiting Power PH Charlton Abbots PH11 Cross over A 435 road SP UPPER COBERLEY. strenuous climbs and steep B4216 Prestbury Railway Lines Highleadon Extreme Care crossing A435. Aston Crews Staverton Hawling PH Upper Slaughter descents. -

The Old Farmhouse Lower Apperley, Nr Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire

THE OLD FARMHOUSE Lower Apperley, Nr Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire THE OLD FARMHOUSE, LOWER APPERLEY, NR TEWKESBURY, GLOUCESTERSHIRE An attractive and well-proportioned Grade II listed country residence with paddocks, stabling and mill house MILEAGES: Tewkesbury 6 miles w Cheltenham 9 miles w Ledbury 13 miles w Worcester 23 miles w M5 (Junction 10) 6 miles (All distances are approximate) THE OLD FARMHOUSE Ground Floor Entrance porch w reception hall w kitchen & breakfast room w boot room w drawing room w further reception room First Floor Master bedroom with en suite bathroom and dressing room w four further bedrooms w two bathrooms Cellar Mill house w workshop w stables Land totalling about 8 acres Savills Cheltenham The Quadrangle, Imperial Square, Cheltenham, GL50 1PZ [email protected] 01242 548000 savills.co.uk SITUATION The Old Farmhouse is situated in a picturesque and private location within the village of Lower Apperley. The village is surrounded by gentle countryside and is located in the heart of the Severn Vale. The adjacent village of Apperley is located within a few hundred yards and the two villages together provide amenities which include a village hall, two pubs and a primary school. Access to local and regional communications is good with the A38 about 2 miles away and M5 junction 10 about 6 miles. Gloucester station has direct trains to London Paddington and is just 8 miles away. DESCRIPTION The Old Farmhouse is an attractive Grade II listed period property situated in a private and slightly elevated location with driveway and water feature to the front and gardens plus paddocks to the side and rear. -

7-Night Cotswolds Guided Walking Holiday

7-Night Cotswolds Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Cotswolds & England Trip code: BNBOB-7 1 & 2 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Gentle hills, picture-postcard villages and tempting tea shops make this quintessentially English countryside perfect for walking. On our Guided Walking holidays you'll discover glorious golden stone villages with thatched cottages, mansion houses, pastoral countryside and quiet country lanes. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 5 days guided walking and 1 free day • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point • Choice of up to three guided walks each walking day • The services of HF Holidays Walking Leaders www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Explore the beautiful countryside and rich history of the Cotswolds • Gentle hills, picture-postcard villages and tempting tea shops make this quintessentially English countryside perfect for walking • Let your leader bring the picturesque countryside and history of the Cotswolds to life • In the evenings relax and enjoy the period features and historic interest of Harrington House ITINERARY Version 1 Day 1: Arrival Day You're welcome to check in from 4pm onwards. Enjoy a complimentary Afternoon Tea on arrival. Day 2: South Along The Windrush Valley Option 1 - The Quarry Lakes And Salmonsbury Camp Distance: 6½ miles (10.5km) Ascent: 400 feet (120m) In Summary: A circular walk starts out along the Monarch’s Way reaching the village of Clapton-on-the-Hill. We return along the Windrush valley back to Bourton. -

Benefice Profile the Northleach Benefice Gloucestershire Benefice Profile

Benefice Profile The Northleach Benefice Gloucestershire Benefice Profile We seek a Priest In Charge for our Benefice, set in a beautiful area of the Cotswolds. This is a great opportunity for someone with energy, enthusiasm, an outgoing nature and love of the countryside. God’s love shines within and through the eight parish communities in our Benefice and there’s the opportunity to develop this in a cohesive way. We have solid foundations, lots of talent, enthusiasm and potential. We’re ready to be inspired! We want to work with our new incumbent to continue moving forward in the love and unity of Christ. Contents Our Mission and Values ........................................................ 4 About the Benefice: Our Location ............................................................... 5 Our Local Population ................................................. 6 Our Schools ................................................................. 7 Today’s Benefice ......................................................... 9 Northleach Parish .................................................................. 11 Cold Aston Parish .................................................................. 13 Compton Abdale Parish ........................................................ 14 Hampnett Parish .................................................................... 14 Hazleton Parish ..................................................................... 15 Notgrove Parish ..................................................................... 15 Turkdean -

Pinchins Cottage Notgrove

Pinchins Cottage Notgrove People Property Places A quintessential Cotswold cottage in an idyllic rural position with lovely views on the edge of this delightful village. The Property Pinchins Cottage is Listed Grade 11 as a building of special architectural or historic interest. It is thought to date back to the late 17th Century – mid 18th Century with later extensions. Traditionally constructed of Cotswold stone walls with mullioned windows and a Cotswold slate roof, it stands in about half an acre of garden. A traditional planked front door leads into the living room with an inglenook fireplace, a wood burning stove with a bricked up bread oven, door to built in cupboard and window seat. To the rear there is a study/bedroom 3. From the living room a door leads into a dining room with a fireplace having a stone chimney piece, wood block floor and under stairs storage cupboard. The kitchen has black and white tiled flooring and a range of modern fitted base and wall cabinets with laminated work surfaces, a four ring hob with electric oven below, a single drainer sink and plumbing for washing machine and dishwasher. There is a large well shelved larder/pantry and a further large cupboard housing the immersion heater and shelving for laundry. The rear hall houses the oil fired boiler providing heating throughout the cottage. There is a downstairs cloakroom with WC and washbasin. From the dining room a staircase leads to the first floor landing off which doors lead to two good double bedrooms (with beams) and a bathroom fitted with a white suite of bath with shower over, washbasin and WC. -

T 01451 820913 Bourton-On-The-Water Established 200 Years

established 200 years Folly Farm Cottage Guide price £450,000 Notgrove Road, Cold Aston A substantial semi-detached 3 bedroom house with stables and barn, offering further potential subject to any necessary consents. taylerandfletcher.co.uk T 01451 820913 Bourton-on-the-Water established 200 years DESCRIPTION Bourton-on-the-Water 3 miles, Stow-on-the-Wold 6.5 Folly Farm Cottage comprises a surprisingly substantial miles, Cheltenham 13.5 miles, Cirencester 15 miles, semi-detached property extended by the current owners to Kingham (Mainline Station) 11.5 miles add a garden room, utility and ground floor shower room and offering further potential subject to any necessary consents. The property would benefit from some further Folly Farm Cottage improvement and updating and provides accommodation Notgrove Road arranged over three floors with a garden room, sitting room, kitchen/dining room and utility/shower room on the ground Cold Aston floor. Two double bedrooms, a family bathroom and Gloucestershire secondary landing/ study and stairs rising to the top floor bedroom with en suite cloakroom. GL54 3BP Approach A SUBSTANTIAL SEMI-DETACHED 3 BEDROOM UPVC double glazed front door with canopy to the front, HOUSE WITH STABLES AND BARN, OFFERING leading to the: FURTHER POTENTIAL SUBJECT TO ANY NECESSARY CONSENTS. Staircase Hall With stairs rising to the first floor, below stairs storage and painted timber door to: • Semi-Detached House Sitting Room With wide double glazed casement window to front elevation • Sitting Room, Garden Room and separate door interconnecting to the kitchen/ dining • Kitchen/ Dining Room room and open fireplace with hearth with stone lintel over and three wall light points, • Utility/ Shower Room From the hall, glazed timber door to: • 2 First Floor Bedrooms, Bathroom • Second Floor Bedroom with En Suite WC • Stables, Barn • Hay Store • EPC Rating E VIEWING Strictly by prior appointment through Tel: 01451 820913 DIRECTIONS From Bourton-on-the-Water take the A436 towards Cheltenham. -

Gloucestershire Parish Map

Gloucestershire Parish Map MapKey NAME DISTRICT MapKey NAME DISTRICT MapKey NAME DISTRICT 1 Charlton Kings CP Cheltenham 91 Sevenhampton CP Cotswold 181 Frocester CP Stroud 2 Leckhampton CP Cheltenham 92 Sezincote CP Cotswold 182 Ham and Stone CP Stroud 3 Prestbury CP Cheltenham 93 Sherborne CP Cotswold 183 Hamfallow CP Stroud 4 Swindon CP Cheltenham 94 Shipton CP Cotswold 184 Hardwicke CP Stroud 5 Up Hatherley CP Cheltenham 95 Shipton Moyne CP Cotswold 185 Harescombe CP Stroud 6 Adlestrop CP Cotswold 96 Siddington CP Cotswold 186 Haresfield CP Stroud 7 Aldsworth CP Cotswold 97 Somerford Keynes CP Cotswold 187 Hillesley and Tresham CP Stroud 112 75 8 Ampney Crucis CP Cotswold 98 South Cerney CP Cotswold 188 Hinton CP Stroud 9 Ampney St. Mary CP Cotswold 99 Southrop CP Cotswold 189 Horsley CP Stroud 10 Ampney St. Peter CP Cotswold 100 Stow-on-the-Wold CP Cotswold 190 King's Stanley CP Stroud 13 11 Andoversford CP Cotswold 101 Swell CP Cotswold 191 Kingswood CP Stroud 12 Ashley CP Cotswold 102 Syde CP Cotswold 192 Leonard Stanley CP Stroud 13 Aston Subedge CP Cotswold 103 Temple Guiting CP Cotswold 193 Longney and Epney CP Stroud 89 111 53 14 Avening CP Cotswold 104 Tetbury CP Cotswold 194 Minchinhampton CP Stroud 116 15 Bagendon CP Cotswold 105 Tetbury Upton CP Cotswold 195 Miserden CP Stroud 16 Barnsley CP Cotswold 106 Todenham CP Cotswold 196 Moreton Valence CP Stroud 17 Barrington CP Cotswold 107 Turkdean CP Cotswold 197 Nailsworth CP Stroud 31 18 Batsford CP Cotswold 108 Upper Rissington CP Cotswold 198 North Nibley CP Stroud 19 Baunton -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'. -

Brian Knight

STRATEGY, MISSION AND PEOPLE IN A RURAL DIOCESE A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF THE DIOCESE OF GLOUCESTER 1863-1923 BRIAN KNIGHT A thesis submitted to the University of Gloucestershire in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities August, 2002 11 Strategy, Mission and People in a Rural Diocese A critical examination of the Diocese of Gloucester 1863-1923 Abstract A study of the relationship between the people of Gloucestershire and the Church of England diocese of Gloucester under two bishops, Charles John Ellicott and Edgar Charles Sumner Gibson who presided over a mainly rural diocese, predominantly of small parishes with populations under 2,000. Drawing largely on reports and statistics from individual parishes, the study recalls an era in which the class structure was a dominant factor. The framework of the diocese, with its small villages, many of them presided over by a squire, helped to perpetuate a quasi-feudal system which made sharp distinctions between leaders and led. It is shown how for most of this period Church leaders deliberately chose to ally themselves with the power and influence of the wealthy and cultured levels of society and ostensibly to further their interests. The consequence was that they failed to understand and alienated a large proportion of the lower orders, who were effectively excluded from any involvement in the Church's affairs. Both bishops over-estimated the influence of the Church on the general population but with the twentieth century came the realisation that the working man and women of all classes had qualities which could be adapted to the Church's service and a wider lay involvement was strongly encouraged. -

Waste Core Strategy (WCS) for Gloucestershire (2012) Notes That Suitable Wastes Are Being Used at Some Mineral Sites for Reclamation Purposes

MMiinneerraallss LLooccaall PPllaann SSiittee OOppttiioonnss aanndd DDrraafftt PPoolliiccyy FFrraammeewwoorrkk EEvviiddeennccee PPaappeerr PPllaannnniinngg aanndd EEnnvviirroonnmmeennttaall CCoonnssiiddeerraattiioonnss June 2014 Page | 2 Contents 1.0 Introduction 3 2.0 Climate change 5 3.0 The Water Environment 14 4.0 Landscape 28 5.0 Green Belt 37 6.0 Nature Conservation (Biodiversity and Geodiversity) 41 7.0 Historic Environment 61 8.0 Transport 76 9.0 Minerals Restoration 88 10.0 Development Management 109 Appendix A Glossary and list of Abbreviations 121 Appendix B Appendix to Section 3 (EA response to Issues and Options) 122 Appendix C Appendix to Section 6 (References and Maps) 124 Appendix D Appendix to Section 7 (References) 128 Appendix E Appendix to Section 8 (Freight Map) 129 Appendix F Appendix to Section 9 (MLP Restoration Policies) 130 Appendix G Appendix to Section 10 (Section 8 of Validation Checklist) 132 P a g e | 3 1.0 Introduction 1.1.1 This paper forms part of the evidence base intended to support the Gloucestershire Minerals Local Plan Site Options and Draft Policy Framework consultation. It contains details of the main planning and environmental policy considerations for minerals planning including climate change, flood risk, landscape, green belt, nature conservation, the historic environment, transport, minerals restoration and development management policies. 1.1.2 Technical issues relating to minerals development and planning such the as types and quantity of minerals required for the plan period and development are discussed in the companion minerals technical evidence paper. There are also supporting papers covering site options for strategic sites for aggregates, the local aggregates assessment and also a separate paper considering the policy framework for minerals safeguarding areas.