Bloody Morgan” Ian Fleming’S Use of the Pirate Motif

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 English Form3.Pdf

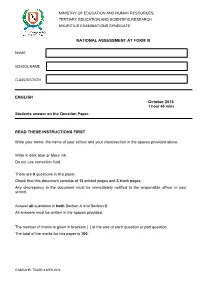

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND HUMAN RESOURCES, TERTIARY EDUCATION AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH MAURITIUS EXAMINATIONS SYNDICATE NATIONAL ASSESSMENT AT FORM III NAME SCHOOL NAME CLASS/SECTION ENGLISH October 2016 1 hour 45 mins Students answer on the Question Paper. READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS FIRST Write your name, the name of your school and your class/section in the spaces provided above. Write in dark blue or black ink. Do not use correction fluid. There are 9 questions in this paper. Check that this document consists of 13 printed pages and 3 blank pages. Any discrepancy in the document must be immediately notified to the responsible officer in your school. Answer all questions in both Section A and Section B. All answers must be written in the spaces provided. The number of marks is given in brackets [ ] at the end of each question or part question. The total of the marks for this paper is 100. © MoE&HR, TE&SR & MES 2016 1 Please turn over this page SECTION A: READING (40 Marks) 1. Read the following text. This is the story of a French pirate who turned to piracy for fun and left behind a mystery – perhaps even a treasure – that lasts to this day. 1 Olivier Levasseur was born in the town of Calais, in northern France, in 1689. His family was wealthy and he was sent to the best schools in France. After receiving an excellent education, he became an officer in the French Navy. During the war of Spanish succession (1701 – 1714), he got his own ship and he became a privateer, someone whose job is to capture enemy ships and keep a percentage of their goods. -

Pirates: a General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pirates Pdf

FREE PIRATES: A GENERAL HISTORY OF THE ROBBERIES AND MURDERS OF THE MOST NOTORIOUS PIRATES PDF Charles Johnson | 384 pages | 15 Jul 2002 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9780851779195 | English | London, United Kingdom Book Review - A General History by Daniel Defoe Seller Rating:. About this Item: Lyons Press. Condition: Good. Used books may not include access codes or one time use codes. Proven Seller with Excellent Customer Service. Choose expedited shipping and get it FAST. Seller Inventory CON More information about this seller Contact this seller 1. About this Item: Basic Books. Condition: GOOD. Spine creases, wear to binding and pages from reading. May contain limited notes, underlining or highlighting that does affect the text. Possible ex library copy, will have the markings and stickers associated from the library. Accessories such as CD, codes, toys, may not be included. Seller Inventory More information about this seller Contact this seller 2. Published by Basic Books About this Item: Basic Books, Connecting readers with great books since Customer service is our top priority!. More information about this seller Contact this seller 3. Published by Globe Pequot Press, The Shows some signs of wear, and may have some markings on the inside. More information about this seller Contact this seller 4. More information about this seller Contact this seller 5. More information about this seller Contact this seller 6. Published by Lyons Press About this Item: Lyons Press, Pirates: A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pirates Satisfaction Guaranteed! Book is in Used-Good condition. Pages and cover are clean and intact. -

The James Bond Quiz Eye Spy...Which Bond? 1

THE JAMES BOND QUIZ EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 1. 3. 2. 4. EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 5. 6. WHO’S WHO? 1. Who plays Kara Milovy in The Living Daylights? 2. Who makes his final appearance as M in Moonraker? 3. Which Bond character has diamonds embedded in his face? 4. In For Your Eyes Only, which recurring character does not appear for the first time in the series? 5. Who plays Solitaire in Live And Let Die? 6. Which character is painted gold in Goldfinger? 7. In Casino Royale, who is Solange married to? 8. In Skyfall, which character is told to “Think on your sins”? 9. Who plays Q in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service? 10. Name the character who is the head of the Japanese Secret Intelligence Service in You Only Live Twice? EMOJI FILM TITLES 1. 6. 2. 7. ∞ 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10. GUESS THE LOCATION 1. Who works here in Spectre? 3. Who lives on this island? 2. Which country is this lake in, as seen in Quantum Of Solace? 4. Patrice dies here in Skyfall. Name the city. GUESS THE LOCATION 5. Which iconic landmark is this? 7. Which country is this volcano situated in? 6. Where is James Bond’s family home? GUESS THE LOCATION 10. In which European country was this iconic 8. Bond and Anya first meet here, but which country is it? scene filmed? 9. In GoldenEye, Bond and Xenia Onatopp race their cars on the way to where? GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 1. In which Bond film did the iconic Aston Martin DB5 first appear? 2. -

Thomas Tew and Pirate Settlements of the Indo - Atlantic Trade World, 1645 -1730 1 Kevin Mcdonald Department of History University of California, Santa Cruz

‘A Man of Courage and Activity’: Thomas Tew and Pirate Settlements of the Indo - Atlantic Trade World, 1645 -1730 1 Kevin McDonald Department of History University of California, Santa Cruz “The sea is everything it is said to be: it provides unity, transport , the means of exchange and intercourse, if man is prepared to make an effort and pay a price.” – Fernand Braudel In the summer of 1694, Thomas Tew, an infamous Anglo -American pirate, was observed riding comfortably in the open coach of New York’s only six -horse carriage with Benjamin Fletcher, the colonel -governor of the colony. 2 Throughout the far -flung English empire, especially during the seventeenth century, associations between colonial administrators and pirates were de rig ueur, and in this regard , New York was similar to many of her sister colonies. In the developing Atlantic world, pirates were often commissioned as privateers and functioned both as a first line of defense against seaborne attack from imperial foes and as essential economic contributors in the oft -depressed colonies. In the latter half of the seventeenth century, moreover, colonial pirates and privateers became important transcultural brokers in the Indian Ocean region, spanning the globe to form an Indo-Atlantic trade network be tween North America and Madagascar. More than mere “pirates,” as they have traditionally been designated, these were early modern transcultural frontiersmen: in the process of shifting their theater of operations from the Caribbean to the rich trading grounds of the Indian Ocean world, 1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the “Counter -Currents and Mainstreams in World History” conference at UCLA on December 6-7, 2003, organized by Richard von Glahn for the World History Workshop, a University of California Multi -Campus Research Unit. -

Captain Blood by Rafael Sabatini</H1>

Captain Blood by Rafael Sabatini Captain Blood by Rafael Sabatini Captain Blood, by Rafael Sabatini CAPTAIN BLOOD His Odyssey CONTENTS I. THE MESSENGER II. KIRKE'S DRAGOONS III. THE LORD CHIEF JUSTICE IV. HUMAN MERCHANDISE V. ARABELLA BISHOP VI. PLANS OF ESCAPE VII. PIRATES VIII. SPANIARDS IX. THE REBELS-CONVICT X. DON DIEGO XI. FILIAL PIETY XII. DON PEDRO SANGRE page 1 / 543 XIII. TORTUGA XIV. LEVASSEUR'S HEROICS XV. THE RANSOM XVI. THE TRAP XVII. THE DUPES XVIII. THE MILAGROSA XIX. THE MEETING XX. THIEF AND PIRATE XXI. THE SERVICE OF KING JAMES XXIII. HOSTAGES XXIV. WAR XXV. THE SERVICE OF KING LOUIS XXVI. M. DE RIVAROL XXVII. CARTAGENA XXVIII. THE HONOUR OF M. DE RIVAROL XXIX. THE SERVICE OF KING WILLIAM XXX. THE LAST FIGHT OF THE ARABELLA XXXI. HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR CHAPTER I THE MESSENGER Peter Blood, bachelor of medicine and several other things besides, smoked a pipe and tended the geraniums boxed on the sill of his window above Water Lane in the town of Bridgewater. page 2 / 543 Sternly disapproving eyes considered him from a window opposite, but went disregarded. Mr. Blood's attention was divided between his task and the stream of humanity in the narrow street below; a stream which poured for the second time that day towards Castle Field, where earlier in the afternoon Ferguson, the Duke's chaplain, had preached a sermon containing more treason than divinity. These straggling, excited groups were mainly composed of men with green boughs in their hats and the most ludicrous of weapons in their hands. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Welcome from the Dais ……………………………………………………………………… 1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Background Information ……………………………………………………………………… 3 The Golden Age of Piracy ……………………………………………………………… 3 A Pirate’s Life for Me …………………………………………………………………… 4 The True Pirates ………………………………………………………………………… 4 Pirate Values …………………………………………………………………………… 5 A History of Nassau ……………………………………………………………………… 5 Woodes Rogers ………………………………………………………………………… 8 Outline of Topics ……………………………………………………………………………… 9 Topic One: Fortification of Nassau …………………………………………………… 9 Topic Two: Expulsion of the British Threat …………………………………………… 9 Topic Three: Ensuring the Future of Piracy in the Caribbean ………………………… 10 Character Guides …………………………………………………………………………… 11 Committee Mechanics ……………………………………………………………………… 16 Bibliography ………………………………………………………………………………… 18 1 Welcome from the Dais Dear delegates, My name is Elizabeth Bobbitt, and it is my pleasure to be serving as your director for The Republic of Pirates committee. In this committee, we will be looking at the Golden Age of Piracy, a period of history that has captured the imaginations of writers and filmmakers for decades. People have long been enthralled by the swashbuckling tales of pirates, their fame multiplied by famous books and movies such as Treasure Island, Pirates of the Caribbean, and Peter Pan. But more often than not, these portrayals have been misrepresentations, leading to a multitude of inaccuracies regarding pirates and their lifestyle. This committee seeks to change this. In the late 1710s, nearly all pirates in the Caribbean operated out of the town of Nassau, on the Bahamian island of New Providence. From there, they ravaged shipping lanes and terrorized the Caribbean’s law-abiding citizens, striking fear even into the hearts of the world’s most powerful empires. Eventually, the British had enough, and sent a man to rectify the situation — Woodes Rogers. In just a short while, Rogers was able to oust most of the pirates from Nassau, converting it back into a lawful British colony. -

Let Privateers Marque Terrorism: a Proposal for a Reawakening

Indiana Law Journal Volume 82 Issue 1 Article 5 Winter 2007 Let Privateers Marque Terrorism: A Proposal for a Reawakening Robert P. DeWitte Indiana University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the International Law Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation DeWitte, Robert P. (2007) "Let Privateers Marque Terrorism: A Proposal for a Reawakening," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 82 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol82/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Let Privateers Marque Terrorism: A Proposal for a Reawakening ROBERT P. DEWrrE* INTRODUCTION In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, the United States has repeatedly emphasized the asymmetry between traditional war and the War on TerrorlI-an unorthodox conflict centered on a term which has been continuously reworked and reinvented into its current conception as the "new terrorism." In this rendition of terrorism, fantasy-based ideological agendas are severed from state sponsorship and supplemented with violence calculated to maximize casualties.' The administration of President George W. Bush reinforced and legitimized this characterization with sweeping demonstrations of policy revolution, comprehensive analysis of intelligence community failures,3 and the enactment of broad legislation tailored both to rectify intelligence failures and provide the national security and law enforcement apparatus with the tools necessary to effectively prosecute the "new" war.4 The United States also radically altered its traditional reactive stance on armed conflict by taking preemptive action against Iraq-an enemy it considered a gathering threat 5 due to both state support of terrorism and malignant belligerency. -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

This Month in Latin American History March 12, 1671 Henry Morgan

This Month in Latin American History Depiction of the sack of Panama March 12, 1671 Henry Morgan returns to Port Royal following the sack of Panama As convoys of silver and other valuable cargo Between Spain and its New World colonies grew, Spain’s European rivals sought ways to profit from that trade. One of the most common tactics was to hire privateers- licensed pirates who sought to pick off ships or raid coastal communities along the main trade routes. In the 1660s, one of the most successful privateers was Henry Morgan of Wales, who had already staged several successful raids around the Caribbean before undertaking his most daring assault yet- an attack on Panama City. Even Before the construction of the Panama Canal in the early 20th century, the city was a crucial nexus of trade, But since it was on the Pacific side of the isthmus, the defenders were not prepared for Morgan’s force, which landed on the Caribbean side and marched across difficult terrain, taking the city almost completely By surprise. Despite the Spanish governor destroying most of the city’s treasury, Morgan’s crew remained for three weeks, and in the aftermath the Spanish reBuilt Panama city in a different, more defensible location. Upon his return to Port Royal, Jamaica, Morgan received a hero’s welcome, But not long afterward he was arrested, since he had technically broken a peace treaty between England and Spain. Though never punished, the Crown made it clear that Morgan was to retire- he was named deputy governor of Jamaica and awarded a large estate there, where he lived out his days in luxury. -

SUPPORTING DOCUMENTATION Privateering and Piracy in The

SUPPORTING DOCUMENTATION Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions Matthew McCarthy The execution of ten pirates at Port Royal, Jamaica in 1823 Charles Ellms, The Pirates Own Book (Gutenberg eBook) http://www.gutenberg.org/files/12216/12216-h/12216-h.htm Please include the following citations when quoting from this dataset: CITATIONS (a) The dataset: Matthew McCarthy, Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions (online dataset, 2012), http://www.hull.ac.uk/mhsc/piracy-mccarthy (b) Supporting documentation: Matthew McCarthy, ‘Supporting Documentation’ in Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions (online dataset, 2012), http://www.hull.ac.uk/mhsc/piracy-mccarthy 1 Summary Dataset Title: Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions Subject: Prize actions between potential prize vessels and private maritime predators (privateers and pirates) during the Spanish American Revolutions (c.1810- 1830) Data Provider: Matthew McCarthy Maritime Historical Studies Centre (MHSC) University of Hull Email: [email protected] Data Editor: John Nicholls MHSC, University of Hull [email protected] Extent: 1688 records Keywords: Privateering, privateer, piracy, pirate, predation, predator, raiding, raider, prize, commerce, trade, slave trade, shipping, Spanish America, Latin America, Hispanic America, independence, revolution, maritime, history, nineteenth century Citations (a) The dataset: Matthew McCarthy, Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions (online dataset, 2012), http://www.hull.ac.uk/mhsc/piracy-mccarthy (b) Supporting documentation: Matthew McCarthy, ‘Supporting Documentation’ in Privateering and Piracy in the Spanish American Revolutions (online dataset, 2012), http://www.hull.ac.uk/mhsc/piracy-mccarthy 2 Historical Context Private maritime predation was integral to the Spanish American Revolutions of the early nineteenth century. -

The 007Th Minute Ebook Edition

“What a load of crap. Next time, mate, keep your drug tripping private.” JACQUES A person on Facebook. STEWART “What utter drivel” Another person on Facebook. “I may be in the minority here, but I find these editorial pieces to be completely unreadable garbage.” Guess where that one came from. “No, you’re not. Honestly, I think of this the same Bond thinks of his obituary by M.” Chap above’s made a chum. This might be what Facebook is for. That’s rather lovely. Isn’t the internet super? “I don’t get it either and I don’t have the guts to say it because I fear their rhetoric or they’d might just ignore me. After reading one of these I feel like I’ve walked in on a Specter round table meeting of which I do not belong. I suppose I’m less a Bond fan because I haven’t read all the novels. I just figured these were for the fans who’ve read all the novels including the continuation ones, fan’s of literary Bond instead of the films. They leave me wondering if I can even read or if I even have a grasp of the language itself.” No comment. This ebook is not for sale but only available as a free download at Commanderbond.net. If you downloaded this ebook and want to give something in return, please make a donation to UNICEF, or any other cause of your personal choice. BOOK Trespassers will be masticated. Fnarr. BOOK a commanderbond.net ebook COMMANDERBOND.NET BROUGHT TO YOU BY COMMANDERBOND.NET a commanderbond.net book Jacques I. -

John Barry • Great Movie Sounds of John Barry

John Barry - Great Movie Sounds of John Barry - The Audio Beat - www.TheAudioBeat.Com 29.10.18, 1431 Music Reviews John Barry • Great Movie Sounds of John Barry Columbia/Speakers Corner S BPG 62402 180-gram LP 1963 & 1966/2018 Music Sound by Guy Lemcoe | October 26, 2018 uring his fifty-year career, composer John Barry won five Oscars and four Grammys. Among the scores he produced is my favorite, and what I consider his magnum opus, Dances with Wolves. Barry's music is characterized by bombast tempered with richly harmonious, "loungey," often sensuous melodies. Added to those are dramatic accents of brass, catchy Latin rhythms and creative use of flute, harp, timpani and exotic percussion (such as the talking drums, which feature prominently in the score from Born Free). The Kentonesque brass writing (trumpets reaching for the sky and bass trombones plumbing the lower registers), which helps define the Bond sound, no doubt stems from Barry’s studies with Stan Kenton arranger Bill Russo. I also hear traces of Max Steiner and Bernard Hermann in Barry's scores. When he used vocals, the songs often became Billboard hits. Witness Shirley Bassey’s work on Goldfinger, Tom Jones’s Thunderball, Matt Monro’s From Russia With Love and Born Free, Nancy Sinatra’s You Only Live Twice and Louis Armstrong’s On Her Majesty's Secret Service. Side one of Great Movie Sounds of John Barry features a half-dozen Bond-film flag-wavers -- two each from Thunderball and From Russia With Love and one each from Goldfinger and Dr.