City-HUB Project EUROPEAN COMMISSION SEVENTH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regeneris Report

Redbridge Economic Strategy Development - Baseline A Draft Report by Regeneris Consulting London Borough of Redbridge Redbridge Economic Strategy Development - Baseline 11 March 2016 Regeneris Consulting Ltd www.regeneris.co.uk Contents Page 1. Introduction 4 2. Summary of Existing Policy and Strategy that will Shape the Economic Strategy 5 3. Key Findings from the Local Economic Assessment 2016 9 4. Baseline Note A: Sector and business base – in which sectors is Redbridge growing? 14 5. Baseline Note B: What is the size and shape of the borough’s low carbon economy? 33 6. Baseline Note C: What is the size and shape of the borough’s informal economy? 36 7. Baseline Note D: Why has the business base increased so much recently? 41 8. Baseline Note E: How can the borough attract and support increased higher education? 49 9. Baseline Note F: What are Redbridge’s most important economic linkages? 58 10. Baseline Note G: How does Redbridge perform on wages and productivity? 70 11. Baseline Note H: What are the factors constraining employment in Redbridge? 72 12. Baseline Note I: How does the fairness commission influence the economic strategy? 83 13. Baseline Note J: What is the role of housing in the boroughs economic growth? 85 14. Baseline Note K: How are industrial areas in Redbridge performing? 89 15. Baseline Note L: How are town centres / evening economy performing in Redbridge? 95 16. Baseline Note M: What is the real impact of Crossrail? 105 3 1. Introduction 1.1 The London Borough of Redbridge is developing a new economic strategy that will set out a clear and ambitious vision for growth, building on key assets and opportunities. -

Quality Manual

London School of Social and Management Sciences Pre Arrival Information for International Students September 2019 Version 1 Please note this pre arrival information is based on international students studying in the UK We are delighted that you have been offered a place at London School of Social and Management Sciences and we look forward to welcoming you. The School appreciates and enjoys the cultural diversity brought by international students. The majority of our students are from different parts of the world. The aim of this booklet is to give you some practical advice and information to help you prepare for your arrival and for living and studying in the School. We hope this information will help you plan in advance and make your move to the United Kingdom as smooth as possible. We hope that you will thoroughly enjoy your time with us and get involved in all aspects of the School life. If you have any questions or concerns about coming to study in the United Kingdom, please do contact us so that we can help you. We look forward to meeting you at London School of Social and Management Sciences. With Best Wishes Admissions Team Page 2 of 18 Contents 1. Pre Arrival 5 1.1 Important Issues 5 1.2 Immigration Requirements 5 1.2.1 Introduction 5 1.2.2 Short Term Study (STS) Visa 5 1.2.3 Short-term student (6 months) 6 1.2.4 Eligibility requirements for short-term student routes (6 months) 6 1.2.5 Short-term students and employment 7 Short-term students are not allowed to work in the UK. -

Parking & Travel Plan

Parking & Travel Plan Northbrook Hotel, 24 Northbrook Road, Ilford, Essex, IG1 3BS May 2018 Prepared by: Encon Associates Limited 10 Chapel Lane Arnold Nottingham NG5 7DR A3670 Parking & Travel Plan 24 Northbrook Road, Ilford, IG1 3BS Date of Report: 23 May 2018 Report Reference: A3670 Issued by: MJB Checked by: GM P a g e | 2 May 2018 Parking & Travel Plan 24 Northbrook Road, Ilford, IG1 3BS Contents 1 Introduction ...........................................................................................................4 2 Statement of Intent ..................................................................................................5 3 Existing Site Information ............................................................................................6 4 Staff Travel Survey ...................................................................................................8 5 Parking Plan ...........................................................................................................9 6 Transport Data & Opportunities for Sustainable Travel ..................................................... 11 7 Scope of the Plan ................................................................................................... 16 8 Aims and Objectives ............................................................................................... 17 9 Targets ............................................................................................................... 18 10 Measures ............................................................................................................ -

City-Hub" Project Acronym: City-HUB

EUROPEAN COMMISSION SEVENTH FRAMEWORK COOPERATION WORK PROGRAMME Innovative design and operation of new or upgraded efficient urban transport interchanges THEME [SST.2012.3.1-2.] Collaborative project Grant agreement no: 314262 Project full title: "City-Hub" Project acronym: City-HUB City-HUB Project FINAL REPORT ATTACHED DOCUMENTS TO THE FINAL PUBLISHABLE SUMMARY REPORT Figure 1 City-HUB vision of interchanges. Figure 2 City-HUB surveyed Interchanges Table 1 Terminal related barriers and remedial measures. Barriers Recommendations Involvement of several authorities Definition of a procedural framework with explicit definitions in the decision-making processes. of roles, of each stakeholder. Distinction of ownership and operational responsibilities. Conflicts of economic, societal or Integration of transport planning and land use decisions. environmental interests of Definition of assessment criteria and consultation procedures stakeholders. for interchange implementation. Shortcomings and gaps in the legal Break down of EU level transport policies to the practical level, framework to promote e.g. strategic spatial distribution and mode choices of comprehensive intermodal mobility interchanges. Explore the need for a harmonised European systems. regulatory frame for interconnections. Insufficient public resources to Targeting public sector funding schemes and instruments that finance terminal development facilitate private sector involvement. projects. Absence of a master plan for Regularly update “master plans” of interchanges. interchange -

Harrison Gibson Building 193-207 High Road, Ilford Design & Access Statement September 2016

HARRISON GIBSON BUILDING PLANNING APPLICATION Document Ref No. & Name: 44 Design & Access Statement Author: AWW Date: September 2016 Harrison Gibson Building 193-207 High Road, Ilford Design & Access Statement September 2016 Prepared by: Design Team Revision Record Project Manager:- Issue Date Status Description By Checked Approved Opera - 02/08/2016 DRAFT ISSUE D&A Statement SW IS NM Rev. A 19/08/2016 DRAFT ISSUE D&A Statement SW PS NM Rev. B 24/08/2016 PLANNING ISSUE D&A Statement SW PS NM Architect:- AWW Inspired Environments Rev. C 06/09/2016 PLANNING ISSUE D&A Statement SW PS NM Planning Consultant:- Montagu Evans Quantity Surveyor:- Thomas and Adamson Structural Engineers:- Heyne Tillet Steel MEP Engineers:- MMA Consulting Engineers Landscape Architect:- Barton Willmore EIA Co-ordinator:- RSK Community Consultation:- Bellenden Architectural Visualisation:- AVR London Harrison Gibson Building 3544 – Design & Access Statement, Rev. C 2 File Location: J:\3544\Graphical Design\Presentations\D&A Document Contents 01.00 Introduction ……………………………………………….. p4 02.00 Planning …………………………………………………... p7 03.00 Site Analysis ……………………………………………… .p9 04.00 Constraints and Opportunities …………………………. p30 05.00 Concept Design ………………………………………... p33 06.00 Design Evolution ………………………………………... p38 07.00 Detailed Design Proposal ………………………………. p53 08.00 Technical Design ………………………………………... p90 09.00 Access Statement …………………………………….. p109 Appendix A - General Arrangement Plans ………………………… i Appendix B - Elevations and Sections …………………………… xvi Appendix C - Accommodation -

Trains from Liverpool Street to Ilford ×

trains from liverpool street to ilford × ALL MAPS SHOPPING NEWS IMAGES VIDEOS BOOKS FLIGHTS APPS from Liverpool Street Station, Liverpool Street, London EC2M 7QH, United Kingdom to Ilford, Greater London, UK 00 Leave now 01 02 11:25 - 11:46 20 min › 03 11:30 from Liverpool Street Station 04 4 min 05 11:28 - 11:55 06 26 min › 07 11:29 from Liverpool Street Underground Station 1 min 08 09 11:37 - 12:02 25 min 10 › 11 11:39 from Liverpool Street Underground Station 1 min 0 12 1 13 https://www.google.co.uk/search?q=trains+from+liverpool+street+to+ilford&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8&hl=en-gb&client=safari 21/01/2016, 11:24 Page 1 of 4 1 13 11:29 - 12:02 33 min › › 2 14 11:30 from Liverpool Street Underground Station 3 15 0 min 4 16 5 17 Ilford - National Rail Enquiries - Live Departure Boards m.nationalrail.co.uk › dep › IFD 6 18 Mobile-friendly - Sorry, there are no departures from Ilford in 7the next 219 hours. To find the next available service travelling from this station ... 8 20 London Liverpool Street to Ilford by Train | 12min | Train9 Times21 www.thetrainline-europe.com › train › lo... 10 22 Mobile-friendly21 - January Travel by Train from London Liverpool Street to Ilford in 12m. Get train times 11 23 & buy train ticketsToday for(Thu) London Liverpool ... 22 January 12 24 Tomorrow (Fri) Ilford to London Liverpool Street by Train | 14min | Train13 Times25 www.thetrainline-europe.com23 January › train › ilf... In 2 Days (Sat) 14 26 Mobile-friendly24 - January Travel by Train from Ilford to London Liverpool Street in 14m. -

SURFACE DIRECTORATE C161 Ilford Yard Stabling Project

SURFACE DIRECTORATE C161 Ilford Yard Stabling Project Demolition of existing Greater Anglia Franchise Training (GAF) Centre with use of site as a depot car park and construction of new GAF Training Centre including Back Up Control Facility (BUCF) Town and Country Planning Act Application Planning Statement Incorporating Design & Access Statement Submission Reference: RED/11/8 Document Number: C161-MMD-T-XST-CR112_WS129-50010 London Borough of Redbridge Document uncontrolled once printed. All controlled documents are saved on the CRL Document System © Crossrail Limited Decal Template: CRL1-XRL-Z-ZTM-CR001-50018 Rev.1.0 Town and Country Planning Act Application - Planning Statement RED/11/8 Document Number C161-MMD-T-XST-CR112_WS129-50010 Rev 3.0 Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Application Background .......................................................................................... 5 1.2 Terms of Reference .................................................................................................. 5 1.3 Introduction to Crossrail .......................................................................................... 5 1.4 Introduction to the Planning Statement .................................................................. 6 1.5 Planning and Administrative Context ..................................................................... 6 1.6 Crossrail Construction Code .................................................................................. -

Boundary Commission for England

BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND PROCEEDINGS AT THE 2018 REVIEW OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES IN ENGLAND HELD AT HAVERING TOWN HALL, MAIN HALL, ROMFORD RM1 3BD ON MONDAY 31 OCTOBER 2016 DAY ONE Before: Mr Howard Simmons, The Lead Assistant Commissioner ______________________________ Transcribed from audio by W B Gurney & Sons LLP 83 Victoria Street, London, SW1H 0HW Telephone Number: 0207 960 6089 ______________________________ At 10.00 am THE LEAD ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen and welcome to the hearing today. This is to listen to the initial proposals from the Boundary Commission for the new constituencies in the London area and for members of the public and others to make representations about their views on that. My name is Howard Simmons. I am the Assistant Commissioner responsible for chairing the hearing today. I am supported by both my fellow commissioners, Emma Davy and Richard Wald, and by a team of Boundary Commission staff, led by Tim Bowden, who is on my right. Essentially, Tim will in a moment or two explain about the initial proposals and how people can make representations. The hearing is over two days. Today's is from 10 am ‘til 8 pm this evening. Tomorrow is from 9.00 until 5.00. We appear to have quite a busy schedule, quite a large number of people booked in. I should stress that the hearings today are for people to be able to make their representation not for cross-examination and not for challenge. If there are any questions for clarification, if you could please address those through me as the Chair of the session. -

Multimodal City-Hubs and Their Impact on Local Economy and Land Use Odile Heddebaut, Derek Palmer

Multimodal city-hubs and their impact on local economy and land use Odile Heddebaut, Derek Palmer To cite this version: Odile Heddebaut, Derek Palmer. Multimodal city-hubs and their impact on local economy and land use. 2014. hal-01073030 HAL Id: hal-01073030 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01073030 Submitted on 8 Oct 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Transport Research Arena 2014, Paris Multimodal city-hubs and their impact on local economy and land use Odile Heddebaut *a, Derek Palmer b a Economic and Social Dynamics of Transports (DEST) (IFSTTAR/DEST) IFSTTAR, PRES Université Paris-Est Cité Descartes Boulevard Newton Champs sur marne 77447 MARNE LA VALLÉE CEDEX 2 - France b Transport Research Laboratory (TRL) Crowthorne House, Nine Mile Ride, Wokingham, Berkshire, RG40 3GA, United Kingdom Abstract Within the framework of the “City-Hub” European research project numerous interchanges have been studied in nine countries in Europe. We examine their role in local, regional, national or international transport networks. This article seeks to show the links between transport policies aiming at developing interchanges and urban policies creating development around these stations. -

Crossrail MTR Route | Case Study

Crossrail MTR Route | Case Study Services Supplied on Geo-Environmental Services Ltd was instructed by Invvu Construction Consultants Ltd, to undertake ground investigation supervision for 11 sites along the Crossrail MTR Route from Harold Railway Station through these Projects: to Maryland Railway Station. • Provision of a Construction Phase Plan, A series of trial holes were to be hand excavated by others to support RAMS pack and Task Briefing presenting the foundation design for the new signage. Geo-Environmental were a risk assessment and method state- required to log trial holes and potentially undertake shear vane testing ment(s) specific to the proposed inves- and/or in-situ CBR testing. tigation. • Attendance of a PTS qualified Geo-En- vironmental Engineer to log sixty-six hand dug inspection pits (excavated by others) down to 1.2m bgl, undertake in-situ testing (e.g. hand shear testing, Mexe Cone and DCP CBR) and logging of recovered soils from the exploratory holes. • Provision of factual data from each location: • Harold Wood Railway Station • Brentwood railway station • Manor Park railway station • Gidea Park Railway Station On a project such as this, where engineers are working with contractor’s personnel that they don’t know, Health and Safety is of paramount im- • Romford Railway Station portance. • Seven Kings Railway Station All personnel attending site (whether working on specific tasks, or visit- • Ilford Railway Station ing) had to comply with the safe systems of work as set out in this RAMS • Chadwell Railway Station document in order to achieve the H&S objectives. • Goodmayes Railway Station All site personnel needed to attend a site induction be presented by our • Forest Gate Railway Station Site Engineer prior to commencing works on site. -

Lot 33 Balfour House, 390-398 High Road (A118) Ilford, Greater London IG1 1TL

www.acuitus.co.uk lot 33 Balfour House, 390-398 High Road (A118) Ilford, Greater London IG1 1TL Rent Retail, Office and Educational • Comprises a parade of 6 retail units and • Forecourt and rear car parking £102,600 Investment training centre • Active management potential and residential • Important East London suburb on Crossrail development potential (subject to consents) per annum route exclusive • Nearby occupiers include Howdens Joinery, with one Topps Tiles, Magnet and the County Court retail unit to be let page 52 www.acuitus.co.uk lot 33 N Rent £102,600 per annum The Property exclusive with one retail unit to be let Rear D1 Training Centre N Front Entrance to Training Centre and Solicitor’s Office Extract reproduced from the Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of The Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ©Crown Copyright 100020449. For identification purposes only. Location Description Miles: 12 miles east of Central London The property comprises a parade of six ground floor retail units with forecourt 4.5 miles from Stratford car parking and office/D1 used as a training centre and secure car parking for 10 4 miles south-west of Romford cars at the rear of the ground floor. The office/D1 training centre is accessed Roads: M11, North Circular (A406), A12 separately from the front of the property and has rear access. The property Rail: Ilford Railway Station forms part of a larger building. Newbury Park Underground Station (Central Line) Air: London City Airport, Stansted Airport Tenure Virtual Freehold. Held for a term of 999 years from completion at a peppercorn Situation rent. -

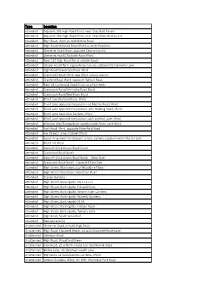

Type Location

Type Location Attended Adjacent 303 High Road Ilford, near Overdraft Tavern Attended Adjacent 266 High Road Ilford, near Chinatown Restaurant Attended High Road, ilford jct with Riches Road Attended High Road/Holstock Road Ilford, outside Pizza Hut Attended Clements Road Ilford, opposite Central Library Attended Clements Road/Chadwick Road Ilford Attended Near 117 High Road Ilford, outside Boots Attended Chapel Road Ilford, opposite Sainsburys, adjacent to Clements Lane Attended High Road/Cranbrook Road Ilford Attended Cranbrook Road Ilford, opp Ilford railway station Attended Cranford Road Ilford, opposite Balfour Road Attended Near 64 Cranbrook Road Ilford, opp Fairheads Attended Cranbrook Road/Wellesley Road Ilford Attended Cranbrook Road/Beal Road Ilford Attended Ilford Lane/Rutland Road, Ilford Attended Ilford Lane opposite the junction of Madras Road, Ilford Attended Ilford Lane opposite the junction with Hickling Road, Ilford Attended Ilford Lane near Vine Gardens, Ilford Attended Ilford Lane opposite the junction with Loxford Lane, Ilford Attended Winston Way Roundabout, junction with Ilford Lane Ilford Attended York Road Ilford, opposite Mansfield Road Attended Ley Street/Hainault Street Ilford Attended Seven Kings High Rd adjacent to 693, camera situated within the car park Attended Ilford Hill Ilford Attended Gants Hill/Cranbrook Road South Attended Cranbrook Road North Attended Gants Hill/Cranbrook Road North – West Side Attended Cranbrook Road North - Gants Hill East Side Attended High Street, Wanstead, opp Woodbine Place