Nazi Secret Warfare in Occupied Persia (Iran)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review and Updated Checklist of Freshwater Fishes of Iran: Taxonomy, Distribution and Conservation Status

Iran. J. Ichthyol. (March 2017), 4(Suppl. 1): 1–114 Received: October 18, 2016 © 2017 Iranian Society of Ichthyology Accepted: February 30, 2017 P-ISSN: 2383-1561; E-ISSN: 2383-0964 doi: 10.7508/iji.2017 http://www.ijichthyol.org Review and updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Iran: Taxonomy, distribution and conservation status Hamid Reza ESMAEILI1*, Hamidreza MEHRABAN1, Keivan ABBASI2, Yazdan KEIVANY3, Brian W. COAD4 1Ichthyology and Molecular Systematics Research Laboratory, Zoology Section, Department of Biology, College of Sciences, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran 2Inland Waters Aquaculture Research Center. Iranian Fisheries Sciences Research Institute. Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization, Bandar Anzali, Iran 3Department of Natural Resources (Fisheries Division), Isfahan University of Technology, Isfahan 84156-83111, Iran 4Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 6P4 Canada *Email: [email protected] Abstract: This checklist aims to reviews and summarize the results of the systematic and zoogeographical research on the Iranian inland ichthyofauna that has been carried out for more than 200 years. Since the work of J.J. Heckel (1846-1849), the number of valid species has increased significantly and the systematic status of many of the species has changed, and reorganization and updating of the published information has become essential. Here we take the opportunity to provide a new and updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Iran based on literature and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history and new fish collections. This article lists 288 species in 107 genera, 28 families, 22 orders and 3 classes reported from different Iranian basins. However, presence of 23 reported species in Iranian waters needs confirmation by specimens. -

From the Great Empire to the Islamic Republic Minorities in Iran: Assimilated Identities, & Denied Rights

From The Great Empire to The Islamic Republic Minorities in Iran: Assimilated Identities, & Denied Rights Tarık Albitar Abstract As the current modern state system is composed of nearly two hundred states that encompass more than five thousand ethnic groups, these groups speak more than three thousand languages. This form of diversity has become a real element within any modern society. Moreover, recognition and respect for these dissimilarities are assumed to be vital for stabilizing domestic affairs and ensure peace and prosperity within a state. In fact, the development of minorities concept came along with/as a result of many factors, one of these factors was the development of other concepts such as nation, citizenship, and superior identity/macro-identity, especially with the rise of remarkable philosophical and intellectual movements during and after the French revolution such as J. J. Rousseau and his social contract. The real development of the minority rights, however, came along with the development of the human rights universalism, which came as a result of the horrifying human losses and the wide-scale of human rights abuses, during the Second World War. Iran, on the other hand, had witnessed enormous historical development; these developments had resulted in creating a widely diversified society in terms of religious views, ethnicities, and linguistic communities. The first national project, however, had failed to emulate the Western model of the modern state and thus was unable to complete its national project, especially after the rise of the Islamic Revolution. On the other hand, the post-revolution Iranian constitution is based on religious interpretations of Islam (Jaafari / Twelfth Shi'a), thus some of the existed minorities are recognized and many others are denied. -

Asala & ARF 'Veterans' in Armenia and the Nagorno-Karabakh Region

Karabakh Christopher GUNN Coastal Carolina University ASALA & ARF ‘VETERANS’ IN ARMENIA AND THE NAGORNO-KARABAKH REGION OF AZERBAIJAN Conclusion. See the beginning in IRS- Heritage, 3 (35) 2018 Emblem of ASALA y 1990, Armenia or Nagorno-Karabakh were, arguably, the only two places in the world that Bformer ASALA terrorists could safely go, and not fear pursuit, in one form or another, and it seems that most of them did, indeed, eventually end up in Armenia (36). Not all of the ASALA veterans took up arms, how- ever. Some like, Alex Yenikomshian, former director of the Monte Melkonian Fund and the current Sardarapat Movement leader, who was permanently blinded in October 1980 when a bomb he was preparing explod- ed prematurely in his hotel room, were not capable of actually participating in the fighting (37). Others, like Varoujan Garabedian, the terrorist behind the attack on the Orly Airport in Paris in 1983, who emigrated to Armenia when he was pardoned by the French govern- ment in April 2001 and released from prison, arrived too late (38). Based on the documents and material avail- able today in English, there were at least eight ASALA 48 www.irs-az.com 4(36), AUTUMN 2018 Poster of the Armenian Legion in the troops of fascist Germany and photograph of Garegin Nzhdeh – terrorist and founder of Tseghakronism veterans who can be identified who were actively en- tia group of approximately 50 men, and played a major gaged in the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh (39), but role in the assault and occupation of the Kelbajar region undoubtedly there were more. -

Sekandar Amanolahi Curriculum Vitae

Sekandar Amanolahi Curriculum Vitae Occupation: Professor of Anthropology E-mail: [email protected]; amanolahi @yahoo.com Phone: 89-7136242180, 617-866-9046 Education: A.A., University of Baltimore, 1964 B.A., Sociology, Morgan State University, 1968 M.A., Anthropology, University of Maryland, 1971 Ph.D., Anthropology, Rice University 1974 Scholarships and Research Grants: University of Maryland, scholarship, 1968-70 Rice University, scholarship, 1971-73 National Science Foundation (through Rice University), Research Grant, 1973 Shiraz University (formerly Pahlavi), scholarship, 1974 Shiraz University, Research Grant, 1976-77 Shiraz University, Research Grant, 1978-80 Harvard University, Fellowship, 1984-85 Namazi Foundation, 1984-85 Harvard University, Grant, summer 1988 National Endowment for Humanities Collaborative Grant, 1990-91 Aarhus University (Denmark) Research Foundation, summer 1991 Bergen University, Council for International Cooperation and Development Studies (Norway) 1991-92 Cultural Heritage Foundation (Center for Anthropological Studies), Research Grant, 1996-97 Shiraz University, Research Grant, 1996-97 Shiraz Municipality, Research Grant, 1997-98 Daito Bunka University (Japan) Fellowship, Summer 1999 UNFPA, Research Grant, University of London, Summer 2004. Fields of Special Interest Culture Change, Ethnic Relations, Tribes Pastoral Nomadism, Peasants, Gypsies, Urbanization, Migration, Globalization Courses Taught: Sociocultural Anthropology, Ethnological Theory, Nomadism, Social History of Iran, Kinship and Family, Rural Sociology, Peoples and Cultures of the Middle East, Introductory Physical Anthropology. Publications: 1970 The Baharvand: Former Pastoralist of Iran, unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology. Rice University. 1974 "The Luti, an Outcast Group of Iran," Rice University Studies, Vol. 61, Mo.2, pp. 1-12 1975 Social Status of Women among the Qashqai (in Persian) Tehran: Women Organization. -

Estimation of Schistosomiosis Infection Rate in the Sheep in Shiraz Region, Fars Province, Iran

Journal of Istanbul Veterınary Scıences Estimation of schistosomiosis infection rate in the sheep in Shiraz region, Fars province, Iran Research Article Gholamreza Karimi1*, Mohammad Abdigoudarzi2 Volume: 4, Issue: 1 1. Razi Vaccine and Serum Research Institute, Department of Parasitology, Agricultural Research, April 2020 Education and Extension Organization, (AREEO), Tehran, Iran. 2. Razi Vaccine and Serum Research Pages: 26-30 Institute, Department of Parasitology, Reference Laboratory for ticks and tick borne research, Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization, (AREEO) Tehran, Iran. Karimi Gh R. ORCOD ID: 0000-0001-8271-5816; Abdigoudarzi M. ORCOD ID: 0000-0002-9239-5972 ABSTRACT Schistosomiosis, due to Schistosoma turkestanicum, is a very important disease. It can cause growth reduction, decrease wool product, reduce meat products and cause weight loss in sheep herds. According to the present records, this disease has spread from the north to the central parts and south of Iran. Stool samples were collected on accidental multiple trials basis from sheep herds, in different seasons of the period of study from 2011 to 2014. The samples were transferred to the laboratory and subjected to direct method and Clayton Lane method. The infection rate was totally 3 percent in the sheep. Different infection rates were observed in seven different places of Dasht Arjan. This rate was from 2 percent in Khane Zenian to 11.2 percent in Chehel Cheshmeh. The minimum number of counted eggs in 1 gram of stool was 1 Article History egg and the maximum counted number of eggs was 6 eggs in 1 gram of stool sample. Received: 10.02.2020 Finally, it should be noted Dashte Arjan is regarded as an infected area and other Accepted: 28.04.2020 Available online: epizootic data on the presence of intermediate host, and different climatological 30.04.2020 factors should also be investigated in the future. -

The Persian-Toledan Astronomical Connection and the European Renaissance

Academia Europaea 19th Annual Conference in cooperation with: Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales, Ministerio de Cultura (Spain) “The Dialogue of Three Cultures and our European Heritage” (Toledo Crucible of the Culture and the Dawn of the Renaissance) 2 - 5 September 2007, Toledo, Spain Chair, Organizing Committee: Prof. Manuel G. Velarde The Persian-Toledan Astronomical Connection and the European Renaissance M. Heydari-Malayeri Paris Observatory Summary This paper aims at presenting a brief overview of astronomical exchanges between the Eastern and Western parts of the Islamic world from the 8th to 14th century. These cultural interactions were in fact vaster involving Persian, Indian, Greek, and Chinese traditions. I will particularly focus on some interesting relations between the Persian astronomical heritage and the Andalusian (Spanish) achievements in that period. After a brief introduction dealing mainly with a couple of terminological remarks, I will present a glimpse of the historical context in which Muslim science developed. In Section 3, the origins of Muslim astronomy will be briefly examined. Section 4 will be concerned with Khwârizmi, the Persian astronomer/mathematician who wrote the first major astronomical work in the Muslim world. His influence on later Andalusian astronomy will be looked into in Section 5. Andalusian astronomy flourished in the 11th century, as will be studied in Section 6. Among its major achievements were the Toledan Tables and the Alfonsine Tables, which will be presented in Section 7. The Tables had a major position in European astronomy until the advent of Copernicus in the 16th century. Since Ptolemy’s models were not satisfactory, Muslim astronomers tried to improve them, as we will see in Section 8. -

Nazismo Alemán Y Emsav Bretón (1933-1945): Entre La Sincera Alianza Y El Engaño Recíproco

HAO, Núm. 30 (Invierno, 2013), 25-38 ISSN 1696-2060 NAZISMO ALEMÁN Y EMSAV BRETÓN (1933-1945): ENTRE LA SINCERA ALIANZA Y EL ENGAÑO RECÍPROCO. José Antonio Rubio Caballero1. 1Universidad de Extremadura E-mail: [email protected] Recibido: 13 Julio 2012 / Revisado: 10 Septiembre 2012 / Aceptado: 26 Enero 2013 / Publicación Online: 15 Febrero 2013 Resumen: Este artículo explora las causas que ideario hitleriano, lo que le llevó a entablar llevaron al Tercer Reich alemán y al contactos con Berlín desde 1933. Llegada la movimiento nacionalista de Bretaña (Emsav) a ocupación alemana de Francia, la relación entre establecer una alianza desde la década de 1930 nazismo y Emsav se fundó sin embargo en más hasta 1945. Según la idea más extendida, la elementos que los anteriormente descritos. En razón de tal colaboración era el deseo alemán de las filas del nacionalsocialismo germano hubo tener aliados en el interior de Francia durante la sectores que no sólo vieron al nacionalismo Segunda Guerra mundial, más la especial bretón como un simple peón de su partida de devoción que el nacionalismo bretón sintió por ajedrez sobre el mapa europeo, sino que la ideología hitleriana. Aunque ello es sintieron también una complicidad ideológica innegable, merece ser matizado, pues la relación con él. El nacionalismo bretón, por su parte, entre nazis y emsaveriens fue más compleja: tampoco estuvo únicamente movido por una también hubo entre los primeros una atracción acrítica devoción hacia Alemania, sino que sincera por la ideología de los segundos, al igual muchos de sus militantes veían al Reich que éstos no actuaron sólo por admiración hacia principalmente como un ariete capaz de demoler el Reich, sino que también el cálculo frío pesó al Estado francés y abrir así las posibilidades de en su decisión de comprometerse con él. -

The Transmission of Astrology Into Abbasid Islam (750-1258 CE)

The Transmission of Astrology into Abbasid Islam (750-1258 CE) © Maria J. Mateus November 27, 2005 Much discussion often arises as to the origins of astrology – most of it centered on whether what we know of the discipline, as it is practiced today, was birthed in Greece, where horoscopy was defined, or in Mesopotamia, where man first began to track the movements of the stars in order to interpret their language. However, the astrological tradition has been long-lived and well proliferated; it may then perhaps, be as accurate to argue that what has come down to us as astrology is as much as multicultural product as it is of either Greek or Babylonian genesis. In its lengthy and diverse history, there have been several significant astrological points of transmission crossroads. One of the most significant cosmopolitan intersections transpired in the Near East after the Islamic conquests of the Sassanian Empire in the 7th century. Arabic astrology as it developed during the Islamic Abbasid Dynasty (750-1258), flourished as a high science which synthesized intellectual influences from Indian, Greek, and Persian scholars, with some cultural influences also streaming in from the Jewish and Sabian traditions. The following essay examines these different streams as they were represented by the Arabic authors and translators active at the Abbasid courts. While I have organized this survey by assigning astrologers to the stream that best represents the language of the majority of sources which they consulted, the majority of the Abbasid astrologers clearly relied on sources from all of these traditions. The Pahlavi Sassanian Stream All of the astrology of Persian origin which has been recovered can be traced to the second great Persian Empire period – that of the Sassanid dynasty (224-642). -

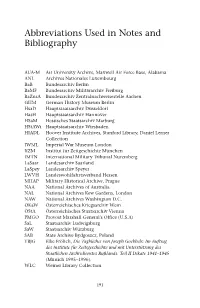

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit Keltisches Gemüse Über ökologischen Landbau und den Sprachkonflikt in der westlichen Bretagne Verfasser Josef Arnold angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 307 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Kultur- und Sozialanthropologie Betreuerin / Betreuer: ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Kraus Eine Studie, die einer nur im Kopf, aber nicht auf dem Papier habe, existiere ja gar nicht, soll Konrad zum Baurat gesagt haben, sagt Wieser. Sie aufschreiben, sie einfach aufschreiben, denke er immer, dieser Gedanke sei es, die Studie einfach aufschreiben, hinsetzen und die Studie aufschreiben (…). Thomas Bernhard: Das Kalkwerk. S 67 Mein Dank gilt meiner Familie, Gerti Seiser, Micha, Stefan, Niko, Gregor, Clemens, Kathi, Steffi, Wolfgang Kraus, Werner Zips und Imke. Hag an tud brezhonek ivez, evel just! Inhaltsverzeichnis Einleitung ............................................................................................................................. 9 Erster Teil: Konstruktion des Feldes .................................................................................. 13 1 Daten und Fakten zur Bretagne.................................................................................. 13 1.1 Abriss der Geschichte.......................................................................................... 13 1.2 Geographie und politische Einteilung ................................................................. 17 1.3 Wirtschaft ........................................................................................................... -

Iran COI Compilation September 2013

Iran COI Compilation September 2013 ACCORD is co-funded by the European Refugee Fund, UNHCR and the Ministry of the Interior, Austria. Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author. ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Iran COI Compilation September 2013 This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared on the basis of publicly available information, studies and commentaries within a specified time frame. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord ACCORD is co-funded by the European Refugee Fund, UNHCR and the Ministry of the Interior, Austria. -

01-707 Carl Otto Lenz

01-707 Carl Otto Lenz ARCHIV FÜR CHRISTLICH-DEMOKRATISCHE POLITIK DER KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG E.V. 01 – 707 CARL OTTO LENZ SANKT AUGUSTIN 2014 I Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Persönliches 1 1.1 Glückwünsche/Kondolenzen 1 1.2 Termine 1 1.3 Pressemeldungen zur Person 2 2 Veröffentlichungen: Beiträge, Reden, Interviews 3 3 CDU Kreisverband Bergstraße 6 4 BACDJ 9 5 Wahlen 10 5.1 Bundestagswahlen 10 5.2 Landtagswahlen Hessen 10 5.3 Kommunalwahlen Hessen 11 5.4 Allgemein 11 6 Deutscher Bundestag 13 6.1 Sachgebiete 13 6.1.1 Verfassungsreform 25 6.1.2 Ehe- und Familienrecht 27 6.2 Ausschüsse 29 6.3 Politische Korrespondenz 31 7 Europa 64 7.1 Materialsammlung Artikel, Aufsätze und Vorträge A-Z 64 7.2 Europäischer Gerichtshof / Materialsammlung A-Z 64 7.2.1 Sachgebiete 64 7.3 Seminare, Konferenzen und Vorträge 64 8 Universitäten 65 9 Sonstiges 66 Sachbegriff-Register 67 Ortsregister 75 Personenregister 76 Biographische Angaben: 5. Juni 1930 Geboren in Berlin 1948 Abitur in München 1949-1956 Studium der Rechts- und Staatswissenschaften an den Universitäten München, Freiburg/Br., Fribourg/Schweiz und Bonn 1954 Referendarexamen 1955-56 Cornell University/USA 1958 Hochschule für Verwaltungswissenschaften in Speyer 1959 Assessorexamen 1961 Promotion zum Dr. jur. in Bonn ("Die Beratungsinstitutionen des amerikanischen Präsidenten in Fragen der allgemeinen Politik") 1957 Eintritt in die CDU 1959-1966 Generalsekretär der CD-Fraktion des Europäischen Parlaments in Straßburg und Luxemburg und 1963-1966 der Parlamentarischen Versammlung der WEU in Paris 1965-1984