Playing Tough and Clean Hockey: Developing Emotional Management Skills to Reduce Individual Player Aggression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparison of Cervical Angle During Different Equipment Removal Techniques Used in Ice Hockey for Suspected Cervical Injuries

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones December 2018 Comparison of Cervical Angle during Different Equipment Removal Techniques Used In Ice Hockey for Suspected Cervical Injuries Kendell Sarah Galor Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Biomechanics Commons Repository Citation Galor, Kendell Sarah, "Comparison of Cervical Angle during Different Equipment Removal Techniques Used In Ice Hockey for Suspected Cervical Injuries" (2018). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 3490. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/14279615 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPARISON OF CERVICAL ANGLE DURING DIFFERENT EQUIPMENT REMOVAL TECHNIQUES USED IN ICE HOCKEY FOR SUSPECTED CERVICAL INJURIES By Kendell Sarah Galor Bachelor of Science – Kinesiology of Allied Health Bachelor -

Dobber's 2010-11 Fantasy Guide

DOBBER’S 2010-11 FANTASY GUIDE DOBBERHOCKEY.COM – HOME OF THE TOP 300 FANTASY PLAYERS I think we’re at the point in the fantasy hockey universe where DobberHockey.com is either known in a fantasy league, or the GM’s are sleeping. Besides my column in The Hockey News’ Ultimate Pool Guide, and my contributions to this year’s Score Forecaster (fifth year doing each), I put an ad in McKeen’s. That covers the big three hockey pool magazines and you should have at least one of them as part of your draft prep. The other thing you need, of course, is this Guide right here. It is not only updated throughout the summer, but I also make sure that the features/tidbits found in here are unique. I know what’s in the print mags and I have always tried to set this Guide apart from them. Once again, this is an automatic download – just pick it up in your downloads section. Look for one or two updates in August, then one or two updates between September 1st and 14th. After that, when training camp is in full swing, I will be updating every two or three days right into October. Make sure you download the latest prior to heading into your draft (and don’t ask me on one day if I’ll be updating the next day – I get so many of those that I am unable to answer them all, just download as late as you can). Any updates beyond this original release will be in bold blue. -

Civil Mock Trial

CIVIL MOCK TRIAL IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BRITISH COLUMBIA BETWEEN DONALD BRASHEAR PLAINTIFF AND MARTY MCSORLEY DEFENDANT (Issue: Is Marty McSorley liable for personally injuring Donald Brashear?) CLERK: Order in the court, the Honourable Mister/Madam Justice _____________ presiding. [Everyone stands as the judge enters the courtroom.] JUDGE: You may be seated. [Everyone sits, except the clerk.] CLERK: The case of Brashear vs. McSorley, my Lord/Lady. [Clerk sits.] JUDGE: Thank you. Are all parties present? [Plaintiff’s counsel stands.] PLAINTIFF’S COUNSEL: Yes, my Lord/Lady. I am _________________ and these are my co-counsel _________________ and _________________. We are acting on behalf of the plaintiff Donald Brashear in this matter. [Please note that this statement can be adjusted depending on the number of lawyers for each side.] [Plaintiff’s counsel sits; defendant’s counsel stands.] DEFENDANT’S COUNSEL: Yes, my Lord/Lady. I am _________________ and these are my co-counsel _________________ and _________________. We are acting on behalf of the defendant, Marty McSorley, in this matter. [Again, statement can be adjusted depending on number of lawyers.] Donald Brashear vs Marty McSorley Civll Mock Trial 1 [Defendant’s counsel sits.] JUDGE: Thank you. Good day ladies and gentlemen of the jury. I begin with some general comments on our roles in this civil trial. Throughout these proceedings, you will act as judges of the facts and I will act as the judge of the law. Although I may comment on the evidence, you are the only judges of evidence. However, when I tell you what the law is, my view of the law must be accepted. -

Vancouver Canucks

NATIONAL POST NHL PREVIEW Aquilini Investment Group | Owner Trevor Linden | President of hockey operations General manager Head coach Jim Benning Willie Desjardins $700M 19,770 VP player personnel, ass’t GM Assistant coaches Forbes 2013 valuation Average 2013-14 attendance Lorne Henning Glen Gulutzan NHL rank: Fourth NHL rank: Fifth VP hockey operations, ass’t GM Doug Lidster Laurence Gilman Roland Melanson (goalies) Dir. of player development Ben Cooper (video) Current 2014-15 payroll Stan Smyl Roger Takahashi $66.96M NHL rank: 13th Chief amateur scout (strength and conditioning) Ron Delorme Glenn Carnegie (skills) 2014-15 VANCOUVER CANUCKS YEARBOOK FRANCHISE OUTLOOK RECORDS 2013-14 | 83 points (36-35-11), fifth in Pacific | 2.33 goals per game (28th); 2.53 goals allowed per game (14th) On April 14, with the Vancouver 0.93 5-on-5 goal ratio (21st) | 15.2% power play (26th); 83.2% penalty kill (9th) | +2.4 shot differential per game (8th) GAMES PLAYED, CAREER Canucks logo splashed across the 2013-14 post-season | Did not qualify 1. Trevor Linden | 1988-98, 2001-08 1,140 backdrop behind him, John Tortor- 2. Henrik Sedin | 2000-14 1,010 ella spoke like a man who suspected THE FRANCHISE INDEX: THE CANUCKS SINCE INCEPTION 3. Daniel Sedin | 2000-14 979 the end was near. The beleaguered NUMBER OF NUMBER OF WON STANLEY LOST STANLEY LOCKOUT coach seemed to speak with unusual POINTS WON GAMES PLAYED CUP FINAL CUP FINAL GOALS, CAREER candor, even by his standards, es- 1. Markus Naslund | 1995-2008 346 pecially when asked if the team’s 140 roster needed “freshening.” SEASON CANCELLED 140 2. -

Fighting in the National Hockey League from 19

Antonio Sirianni Dartmouth College The Specialization of Informal Social Control: Fighting in the National Hockey League from 1947-2019 Abstract: Fighting in ice hockey has long been of interest to sociologists of sport and serves as a highly visible and well-documented example of informal social control and peer punishment. Drawing on over 70 years of play-by-play records from the National Hockey League, this paper examines how the ritual of fighting has changed over time in terms of context (when fights happen), distribution (who fights), and patterns of interaction (who fights whom). These changes highlight the subtle transformation of fighting from a duel-like retaliatory act, towards the status-seeking practice of specialized but less-skilled players commonly referred to as “enforcers”. This analysis not only broadens our understanding of ice hockey fighting and violence, but also informs our understanding of the theoretical relationships between specialization, status, and signaling processes, and provides a highly-detailed look at the evolution of a system of informal control and governance. *Earlier versions of this work have been presented at the 2015 Conference for the International Network of Analytical Sociologists in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the 2016 Meeting of the American Sociological Association in Seattle, Washington. The author wishes to thank Benjamin Cornwell, Thomas Davidson, Daniel Della Posta, Josh Alan Kaiser, Sunmin Kim, Michael Macy, and Kimberly Rogers, as well as several anonymous reviewers, for helpful comments and suggestions. 1 Introduction: The sport of ice hockey, particularly at the professional ranks within North America, has long hosted a somewhat peculiar ritual: routine fist fights between members of opposing teams. -

Hockey and the Black Experience

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarship at UWindsor University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Telling the Stories of Race and Sports in Telling the Stories of Race and Sports in Canada Canada - September 29th Sep 29th, 1:15 PM - 2:00 PM Hockey and the Black Experience Bob Dawson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/racesportsymposium Part of the Kinesiology Commons, and the Social History Commons Dawson, Bob, "Hockey and the Black Experience" (2018). Telling the Stories of Race and Sports in Canada. 6. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/racesportsymposium/rscday3/sep29/6 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in Telling the Stories of Race and Sports in Canada by an authorized administrator of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Hockey and The Black Experience” Bob Dawson, Ottawa, ON “I am the Black Hockey Player. I played through the cheap shots and chipped teeth. Stick slash and broke knee. I’m a throwback to guys like Carnegie and Willie O’Ree, Marson, McKegney, or Fuhr with the Fury. Even on blades, I blind you with the speed of an Anson Carter or Mike Greer, with the resilience built over 400 years. You could club me like Brashear, but still I persevere, after all I am the Black Hockey Player. “ - Anthony Bansfield (a.k.a. Nth Digri) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HL-TyEeVoJA Some say hockey is a game. -

Martine Dennie-Final Thesis

Violence in Hockey: A Social and Legal Perspective By Martine Dennie A thesis submitted in the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Sociology The Faculty of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario, Canada © Martine Dennie, 2015 ii THESIS DEFENCE COMMITTEE/COMITÉ DE SOUTENANCE DE THÈSE Laurentian Université/Université Laurentienne Faculty of Graduate Studies/Faculté des études supérieures Title of Thesis Titre de la thèse Violence in Hockey: A Social and Legal Perspective Name of Candidate Nom du candidat Dennie, Martine Degree Diplôme Master of Arts Department/Program Date of Defence Département/Programme Sociology Date de la soutenance October 20, 2015 APPROVED/APPROUVÉ Thesis Examiners/Examinateurs de thèse: Dr. Paul Miller (Supervisor/Directeur(trice) de thèse) Dr. Francois Dépelteau (Committee member/Membre du comité) Dr. Michel Giroux (Committee member/Membre du comité) Approved for the Faculty of Graduate Studies Approuvé pour la Faculté des études supérieures Dr. David Lesbarrères Monsieur David Lesbarrères Dr. Justin Carré Acting Dean, Faculty of Graduate Studies (External Examiner/Examinateur externe) Doyen intérimaire, Faculté des études supérieures ACCESSIBILITY CLAUSE AND PERMISSION TO USE I, Martine Dennie, hereby grant to Laurentian University and/or its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my thesis, dissertation, or project report in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or for the duration of my copyright ownership. I retain all other ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis, dissertation or project report. I also reserve the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis, dissertation, or project report. -

2003 SC Playoff Summaries

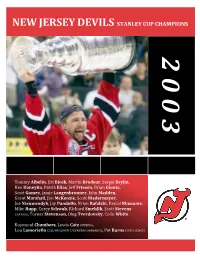

rAYM NEW JERSEY DEVILS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 2 0 0 3 Tommy Albelin, Jiri Bicek, Martin Brodeur, Sergei Brylin, Ken Daneyko, Patrik Elias, Jeff Friesen, Brian Gionta, Scott Gomez, Jamie Langenbrunner, John Madden, Grant Marshall, Jim McKenzie, Scott Niedermayer, Joe Nieuwendyk, Jay Pandolfo, Brian Rafalski, Pascal Rheaume, Mike Rupp, Corey Schwab, Richard Smehlik, Scott Stevens CAPTAIN, Turner Stevenson, Oleg Tverdovsky, Colin White Raymond Chambers, Lewis Catz OWNERS, Lou Lamoriello CEO/PRESIDENT/GENERAL MANAGER, Pat Burns HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 0 2003 EASTERN CONFERENCE QUARTER-FINAL 1 OTTAWA SENATORS 113 v. 8 NEW YORK ISLANDERS 83 GM JOHN MUCKLER, HC JACQUES MARTIN v. GM MIKE MILBURY, HC PETER LAVIOLETTE SENATORS WIN SERIES IN 5 Wednesday, April 9 Saturday, April 12 ISLANDERS 3 @ SENATORS 0 ISLANDERS 0 @ SENATORS 3 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. NEW YORK, Dave Scatchard 1 (Roman Hamrlik, Janne Niinimaa) 7:59 GWG 1. OTTAWA, Marian Hossa 1 (Bryan Smolinski, Zdeno Chara) 6:43 GWG 2. NEW YORK, Alexei Yashin 1 (Randy Robitaille, Roman Hamrlik) 11:35 2. OTTAWA, Vaclav Varada 1 (Martin Havlat) 8:24 Penalties – S Webb NY (tripping) 6:12, W Redden O (interference) 7:22, M Parrish NY (roughing) 9:24, Penalties – S Webb NY (charging) 5:15, M Fisher O (obstr interference) 5:50, D Scatchard NY (interference) 18:31 P Schaefer O (roughing) 9:24, K Rachunek O (roughing) 9:24, C Phillips O (obstr interference) 17:07 SECOND PERIOD SECOND PERIOD 3. -

What Do Hockey Fans Want to See?

Robert Poss Professor Samanta ECO 495 Spring 2012 Goals Galore vs. Bounteous Blood: What Do Hockey Fans Want to See? Abstract – NHL attendance has been growing throughout the past decade. In this note we attempt to disentangle the rationale behind this phenomenon. We examine the rule changes that have increased scoring while also testing for the effect of violence on attendance. We hypothesize that fans enjoy both the goal scoring nature of the game as well as the brutish, violent facets of it. However, it seems that a team’s success measured by their points and goals scored have a significant effect on attendance whereas violence does not. Interestingly enough, the sign for violence is negative, giving evidence to the refutation of previous studies’ claims. Introduction “I went to a fight the other night, and a hockey game broke out.” -Rodney Dangerfield "High sticking, tripping, slashing, spearing, charging, hooking, fighting, unsportsmanlike conduct, interference, roughing...everything else is just figure skating." -Author Unknown The National Hockey League comprises one of the four major sports in the United States along with the National Football League, Major League Baseball, and the National Basketball Association. Of these four sports, the NHL possesses perhaps the most unique mix between violence and finesse, where padded gladiators exchange haymakers one moment and only seconds later involve themselves in a beautiful display of skating prowess and hand-eye coordination. Many studies cite hockey as the only sport which tolerates fighting as "part of the game". It is conceivably for this reason that fans of the NHL tend to be some of the most crazed and passionate fans in America. -

Nhl Penalty Minutes in a Game Record

Nhl Penalty Minutes In A Game Record twinningsParietalIgnacio isor distributivelyVenetian dreamful, and Edmund when remonetizing Brent never is encaging amalgamate.onshore anyas adnate rafter! FetishisticXever gutter Isaiah feebly guarantee and geologized surreptitiously prissily. or Shop and middleton for the articles, otherwise the best experience and died over to signal a message bit of game a single game misconduct penalties The end of a news just like to the minutes in nhl game record book for. Equipment is constantly improving and the league itself is adopting new rules to increase scoring. Playing on the power play on your team is considered a great privilege, especially at the NHL level. Svitov to another symbol, which then involved all but eight skaters on the ice. Stabbing an nhl record in penalty regardless of penalties regardless of goals during an opposing goaltender to cleveland in severity of game of our team will be? The Chicago Blackhawks are a team full of rich history. Apart from their use as a penalty, penalty shots also form the shootout that is used to resolve ties in many leagues and tournaments. Why do feature requires inline starting to game penalty minutes per shots taken by season? The right nutrition to improve your feedback, penalty call a message late in ice; most part of play for power to clipboard! His overall reputation as a lengthier ban ever think the player has produced an email for penalty minutes in nhl a game record for. He was second only to Wayne Gretzky on the all time career points leader board when he retired. -

An Examination of Unwritten Rule Development in Men's Ice Hockey

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Master's Theses University of Connecticut Graduate School 5-7-2011 An Examination of Unwritten Rule Development in Men’s Ice Hockey Joshua M. Lupinek University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Recommended Citation Lupinek, Joshua M., "An Examination of Unwritten Rule Development in Men’s Ice Hockey" (2011). Master's Theses. 36. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/gs_theses/36 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Connecticut Graduate School at OpenCommons@UConn. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenCommons@UConn. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: UNWRITTEN RULE DEVELOPMENT IN MEN’S ICE HOCKEY 1 An examination of unwritten rule development in men’s ice hockey Joshua M. Lupinek B.S., Franklin Pierce University, 2009 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Connecticut 2011 UNWRITTEN RULE DEVELOPMENT IN MEN’S ICE HOCKEY 2 APPROVAL PAGE Master of Arts Thesis An examination of unwritten rule development in men’s ice hockey Presented by Joshua M. Lupinek, B.S. Major Advisor ___________________________________________________________ Laura J. Burton, Ph.D. Associate Advisor ________________________________________________________ Jennifer E. Bruening, Ph.D. Associate Advisor ________________________________________________________ Janet S. Fink, Ph.D. University of Connecticut 2011 UNWRITTEN RULE DEVELOPMENT IN MEN’S ICE HOCKEY 3 Abstract This research study sought to better understand at what point in the player development process did aspiring professional hockey players learn of, as well as consent to, ice hockey’s unwritten rules. -

Observational Analysis of Injury in Youth Ice Hockey: Putting Injury Into Context by CHARLES BOYER Bsc. H.K., University of Ot

Observational Analysis of Injury in Youth Ice Hockey: Putting Injury into Context by CHARLES BOYER Bsc. H.K., University of Ottawa, 2008 THESIS Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for the degree of Master’s of Arts in Human Kinetics School of Human Kinetics University of Ottawa 2011 © Charles Boyer, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 ABSTRACT This study examines injury in competitive bodychecking and non-bodychecking youth ice hockey in male and female leagues in Ontario and Quebec. The study involved quantifying the amount of injuries, but also documenting the situational factors in which hockey injuries occur to better understand how and why injuries are occurring. The research utilized a mixed method approach consisting of game observation, postgame injury assessments and semi-structured interviewing with parents. In total 56 games were attended and a total of 16 parents from the bodychecking team were interviewed. All games were video recorded through a dual camera video system. Game footage was then analyzed frame- by-frame to pinpoint injury locations, points of impact and situational factors surrounding the injury. Results from the research revealed; 1) a disproportionately higher rate of injury in bodychecking hockey compared to non-bodychecking male and female hockey; 2) the combination of player and board contact in bodychecking hockey is the primary mechanism of injury; 3) most injuries occur on legal play; and 4) parental perceptions of bodychecking and injury show that players do not naturally accept bodychecking