An Examination of Unwritten Rule Development in Men's Ice Hockey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ice Hockey Packet # 23

ICE HOCKEY PACKET # 23 INSTRUCTIONS This Learning Packet has two parts: (1) text to read and (2) questions to answer. The text describes a particular sport or physical activity, and relates its history, rules, playing techniques, scoring, notes and news. The Response Forms (questions and puzzles) check your understanding and apprecia- tion of the sport or physical activity. INTRODUCTION Ice hockey is a physically demanding sport that often seems brutal and violent from the spectator’s point of view. In fact, ice hockey is often referred to as a combination of blood, sweat and beauty. The game demands athletes who are in top physical condition and can maintain nonstop motion at high speed. HISTORY OF THE GAME Ice hockey originated in Canada in the 19th cen- tury. The first formal game was played in Kingston, Ontario in 1855. McGill University started playing ice hockey in the 1870s. W. L. Robertson, a student at McGill, wrote the first set of rules for ice hockey. Canada’s Governor General, Lord Stanley of Preston, offered a tro- phy to the winner of the 1893 ice hockey games. This was the origin of the now-famed Stanley Cup. Ice hockey was first played in the U. S. in 1893 at Johns Hopkins and Yale universities, respec- tively. The Boston Bruins was America’s first NHL hockey team. Ice hockey achieved Olym- pic Games status in 1922. Physical Education Learning Packets #23 Ice Hockey Text © 2006 The Advantage Press, Inc. Through the years, ice hockey has spawned numerous trophies, including the following: NHL TROPHIES AND AWARDS Art Ross Trophy: First awarded in 1947, this award goes to the National Hockey League player who leads the league in scoring points at the end of the regular hockey season. -

Bruins Forward Closely Followed at Allston Boxing Club He Trains at - Allston Brighton - Your Town - Boston.Com

Bruins forward closely followed at Allston boxing club he trains at - Allston Brighton - Your Town - Boston.com YOUR TOWN (MORE TOWNS / MORE BOSTON NEIGHBORHOODS) Preferences | Log out Allston Brighton home news events discussions search < Back to front page Text size – + Connect to Allston Brighton ALLSTON BRIGHTON Connect to Your Town Allston Brighton on Bruins forward closely followed Facebook Like You like Your Town Allston- Brighton. · Admin at Allston boxing club he trains ih Follow @ABUpdate on Twitter at Click here to follow Your Town Allston Brighton on Twitter. Posted by Matt Rocheleau June 14, 2011 10:38 PM E-mail | Print | Comments () ADVERTISEMENT (Barry Chin / Globe file) In 2009, Bruins forward Shawn Thornton takes down another hockey enforcer and former teammate - the taller, heavier George Parros. Thornton won the Stanley Cup with Parros and the Anaheim Ducks in 2007 before joining the Bruins the next season. ALLSTON-BRIGHTON REAL ESTATE By Matt Rocheleau, Town Correspondent When Shawn Thornton skates with the Bruins in the franchise’s first-ever 86 160 6 0 Stanley Cup finals Game 7, the team’s enforcer will have a dedicated fan base Homes Rentals Open houses New listings for sale available this week this week from an Allston boxing club cheering him on. Shortly after coming to Boston four years ago, the 33-year-old fighting forward joined The Ring Boxing Club on Commonwealth Avenue after Bruins SPECIAL ADVERTISING DIRECTORY media relations manager Eric Tosi, who had been a member there for around CAMP GUIDE » a year and a half, introduced him to the boxing center. -

NUORET KONKARIT Teksti: Terry Zulynik Kuvat: Dave Sandford/Iihf/Hhof

NUORET KONKARIT teksti: terry zulynik kuvat: dave sandford/iihf/hhof Daniel ja Henrik Sedin ovat nyt, 23-vuotiaina, jo neljän nhl-kauden parkkiinnuttamia kiekkoammattilaisia. Tällä kaudella he tekivät uudet piste-ennätyksensä. Ehkä heitä ei vielä kannatakaan unohtaa? 22.3.2004 – Takana oli tappiot Colum- konferenssin voitosta, jäi pariksi viikoksi bukselle ja Chicagolle, nhl:n huonoim- mediamyrskyyn ja kaukalon ulkopuo- mille joukkueille vielä. Kaikki tiesivät, liset tapahtumat murensivat joukkueen että edessä olisi rankat harjoitukset – ja he pelaajien keskittymisen. Vielä kaksi olivat oikeassa. viikkoa aikaisemmin Canucks oli ollut Kaukalossa oli liian hiljaista, huulen- enemmän kuin vahva ehdokas jopa Stanley heitto ja kujeilu loistivat poissaolollaan. Cup –voittajaksi. Nyt jäällä on murtunut Jäällä oli selvästi Todd Bertuzzin päälle- joukkue, joka nuolee haavojaan, paran- karkauksen jälkiseuraustena mykistämä telee loukkaantumisiaan ja yrittää kaikin ja tainnuttama joukkue. Bertuzzi tyrmäsi keinoin pitää itseluottamusta nakertavat Colorado Avalanchen muutama viikko epäilyt loitolla. aikaisemmin, tunnetuin seurauksin. Siellä jossakin, keskellä kaikkea kohua, Moorelta murtui niskanikama, kun hän kaikkea hälinää, kaikkea järkytystä, ovat kaatui Bertuzzin takaapäin tulleen lyönnin Daniel ja Henrik Sedin, joiden tasaisen voimasta jäähän ja sai kaiken huipuksi varma peli oli Canucksin valopilkkuja päälleen reilun satakiloisen Bertuzzin ja kaudella 2003–04. pari muuta pelaajaa. Bertuzzi sai pelikiel- Vancouver Canucksin toimitusjohta- lon kauden loppuun saakka. ja Brian Burke vaihtoi Bryan McCaben Vancouver Canucks, joka vielä pari ja seuraavan vuoden ykköskierroksen viikkoa aikaisemmin taisteli Läntisen varausvuoron saadakseen Daniel ja Henrik 84 Sedinin samaan nhl-joukkueeseen. Burke Uutuuden viehätys ja adrenaliini siivitti- oli valmis maksamaan Sedineistä aika vätkin heitä ensimmäiset 20 ottelua. Sitten kalliin hinnan – ja mies tunnetaan kovana sarjan rankkuus (Canucks pelasi yhdessä tinkijänä. -

Comparison of Cervical Angle During Different Equipment Removal Techniques Used in Ice Hockey for Suspected Cervical Injuries

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones December 2018 Comparison of Cervical Angle during Different Equipment Removal Techniques Used In Ice Hockey for Suspected Cervical Injuries Kendell Sarah Galor Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Biomechanics Commons Repository Citation Galor, Kendell Sarah, "Comparison of Cervical Angle during Different Equipment Removal Techniques Used In Ice Hockey for Suspected Cervical Injuries" (2018). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 3490. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/14279615 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPARISON OF CERVICAL ANGLE DURING DIFFERENT EQUIPMENT REMOVAL TECHNIQUES USED IN ICE HOCKEY FOR SUSPECTED CERVICAL INJURIES By Kendell Sarah Galor Bachelor of Science – Kinesiology of Allied Health Bachelor -

Peak Performance and Contract Inefficiency in the National Hockey League

PEAK PERFORMANCE AND CONTRACT INEFFICIENCY IN THE NATIONAL HOCKEY LEAGUE A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Economics and Business The Colorado College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Scott Winkler April 2013 PEAK PERFORMANCE AND CONTRACT INEFFICIENCY IN THE NATIONAL HOCKEY LEAGUE Scott Winkler April 2013 Economics Abstract The purpose of this study is to determine what age National Hockey League (NHL) players have their best seasons and how this relates to their contract earnings. The hypothesis is that NHL players have their peak performance at age 27, which indicates that long-term contracts that exceed this age create inefficiency. The study will examine player productivity by taking 30 NHL players and evaluating their performance in the years leading up to age 27 as well as years that follow. Performance measures include average point production and the highest average ice-time per game. The study will also use two OLS (Ordinary Least Squares) regressions where the dependent variables are average time on ice per game and capital hit, both good indicators of how valuable a player is to his team, as well as several statistical independent variables such as points, games played and most importantly age. By gaining knowledge of peak performance, NHL organizations could better manage their teams by limiting long-term contracts to players and as a result lessen the inefficiency that exists in the market. KEYWORDS: (National Hockey League, Performance, Age) TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 1 Introduction………………………………………...…………………………… 1 2 Literature Review……………………..………………………………………… 5 3 Theory……………..……………………..……………………...……………… 11 4 Data and Methodology…………………………..……………………………… 17 4.1 Data Collection……………………………………………………………… 18 4.2 Dependent and Independent Variables……………………………………… 18 5 Results and Analysis……………………………………………….…………… 25 6 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………… 44 6.1 Limitations………………………………………………………..………… 46 6.2 Future Study…………………………..…………………….………………. -

A Matter of Inches My Last Fight

INDEPENDENT PUBLISHERS GROUP A Matter of Inches How I Survived in the Crease and Beyond Clint Malarchuk, Dan Robson Summary No job in the world of sports is as intimidating, exhilarating, and stressridden as that of a hockey goaltender. Clint Malarchuk did that job while suffering high anxiety, depression, and obsessive compulsive disorder and had his career nearly literally cut short by a skate across his neck, to date the most gruesome injury hockey has ever seen. This autobiography takes readers deep into the troubled mind of Clint Malarchuk, the former NHL goaltender for the Quebec Nordiques, the Washington Capitals, and the Buffalo Sabres. When his carotid artery was slashed during a collision in the crease, Malarchuk nearly died on the ice. Forever changed, he struggled deeply with depression and a dependence on alcohol, which nearly cost him his life and left a bullet in his head. Now working as the goaltender coach for the Calgary Flames, Malarchuk reflects on his past as he looks forward to the future, every day grateful to have cheated deathtwice. 9781629370491 Pub Date: 11/1/14 Author Bio Ship Date: 11/1/14 Clint Malarchuk was a goaltender with the Quebec Nordiques, the Washington Capitals, and the Buffalo Sabres. $25.95 Hardcover Originally from Grande Prairie, Alberta, he now divides his time between Calgary, where he is the goaltender coach for the Calgary Flames, and his ranch in Nevada. Dan Robson is a senior writer at Sportsnet Magazine. He 272 pages lives in Toronto. Carton Qty: 20 Sports & Recreation / Hockey SPO020000 6.000 in W | 9.000 in H 152mm W | 229mm H My Last Fight The True Story of a Hockey Rock Star Darren McCarty, Kevin Allen Summary Looking back on a memorable career, Darren McCarty recounts his time as one of the most visible and beloved members of the Detroit Red Wings as well as his personal struggles with addiction, finances, and women and his daily battles to overcome them. -

Vancouver Canucks 2009 Playoff Guide

VANCOUVER CANUCKS 2009 PLAYOFF GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS VANCOUVER CANUCKS TABLE OF CONTENTS Company Directory . .3 Vancouver Canucks Playoff Schedule. 4 General Motors Place Media Information. 5 800 Griffiths Way CANUCKS EXECUTIVE Vancouver, British Columbia Chris Zimmerman, Victor de Bonis. 6 Canada V6B 6G1 Mike Gillis, Laurence Gilman, Tel: (604) 899-4600 Lorne Henning . .7 Stan Smyl, Dave Gagner, Ron Delorme. .8 Fax: (604) 899-4640 Website: www.canucks.com COACHING STAFF Media Relations Secured Site: Canucks.com/mediarelations Alain Vigneault, Rick Bowness. 9 Rink Dimensions. 200 Feet by 85 Feet Ryan Walter, Darryl Williams, Club Colours. Blue, White, and Green Ian Clark, Roger Takahashi. 10 Seating Capacity. 18,630 THE PLAYERS Minor League Affiliation. Manitoba Moose (AHL), Victoria Salmon Kings (ECHL) Canucks Playoff Roster . 11 Radio Affiliation. .Team 1040 Steve Bernier. .12 Television Affiliation. .Rogers Sportsnet (channel 22) Kevin Bieksa. 14 Media Relations Hotline. (604) 899-4995 Alex Burrows . .16 Rob Davison. 18 Media Relations Fax. .(604) 899-4640 Pavol Demitra. .20 Ticket Info & Customer Service. .(604) 899-4625 Alexander Edler . .22 Automated Information Line . .(604) 899-4600 Jannik Hansen. .24 Darcy Hordichuk. 26 Ryan Johnson. .28 Ryan Kesler . .30 Jason LaBarbera . .32 Roberto Luongo . 34 Willie Mitchell. 36 Shane O’Brien. .38 Mattias Ohlund. .40 Taylor Pyatt. .42 Mason Raymond. 44 Rick Rypien . .46 Sami Salo. .48 Daniel Sedin. 50 Henrik Sedin. 52 Mats Sundin. 54 Ossi Vaananen. 56 Kyle Wellwood. .58 PLAYERS IN THE SYSTEM. .60 CANUCKS SEASON IN REVIEW 2008.09 Final Team Scoring. .64 2008.09 Injury/Transactions. .65 2008.09 Game Notes. 66 2008.09 Schedule & Results. -

Backstrom1,000 Nhl Games

NICKLAS BACKSTROM1,000 NHL GAMES ND 2 PLAYER IN FRANCHISE HISTORY TO PLAY 1,000 GAMES WITH THE CAPITALS TH 14 ACTIVE PLAYER TO PLAY 1,000 GAMES WITH ONE FRANCHISE TH 69 PLAYER IN NHL HISTORY TO PLAY 1,000 GAMES WITH ONE FRANCHISE TH 36 ACTIVE PLAYER TO REACH 1,000 GAMES PLAYERS WHO HAD 700+ CAREER ASSISTS BY THEIR MILESTONE GAMES 1,000TH GAME RD PLAYER IN NHL HISTORY 353 OCT. 5, 2007 @ WAYNE GRETZKY 1516 TO REACH 1,000 GAMES 1 PHILIPS ARENA PAUL COFFEY 910 TH NOV. 19, 2008 ADAM OATES 860 @ 14 SWEDISH-BORN PLAYER HONDA CENTER IN NHL HISTORY TO REACH 100 BRYAN TROTTIER 817 1,000 GAMES SIDNEY CROSBY 810 DEC. 19, 2009 @ 200 REXALL PLACE DALE HAWERCHUK 795 RD 23 PLAYER IN NHL HISTORY WITH 700+ MARCEL DIONNE 794 ASSISTS BY THEIR 1,000TH GAME FEB. 6, 2011 VS. 21 of the 23 players to accomplish VERIZON CENTER STEVE YZERMAN 790 this feat are in the Hockey Hall of 300 Fame, while two are not yet eligible DENIS SAVARD 789 (Sidney Crosby, Jaromir Jagr) MARCH 31, 2013 @ RON FRANCIS 780 400 WELLS FARGO CENTER ND RAY BOURQUE 778 2 ACTIVE PLAYER IN NHL HISTORY WITH 700+ ASSISTS BY THEIR MARK MESSIER 778 OCT. 18, 2014 1,000TH GAME (SIDNEY CROSBY) 500 VS. VERIZON CENTER JOE SAKIC 765 BERNIE FEDERKO 761 DEC. 8, 2015 592-296-111 600 VS. VERIZON CENTER JAROMIR JAGR 760 1,295 POINTS WITH BACKSTROM IN THE LINEUP BOBBY CLARKE 754 JAN. 24, 2017 @ 700 CANADIAN TIRE CENTRE GUY LAFLEUR 747 11TH 4TH PHIL ESPOSITO 737 PLAYER IN FRANCHISE PLAYER FROM THE MARCH 8, 2018 HISTORY TO PLAY THEIR 2006 NHL DRAFT @ STAPLES CENTER JARI KURRI 721 1,000TH CAREER GAME CLASS TO REACH THE 800 WITH THE CAPITALS 1,000-GAME MARK DENIS POTVIN 718 OCT. -

Ice Hockey Players

Acta Gymnica, vol. 46, no. 1, 2016, 30–36 doi: 10.5507/ag.2015.027 Assessment of basic physical parameters of current Canadian-American National Hockey League (NHL) ice hockey players Martin Sigmund1,*, Steven Kohn2, and Dagmar Sigmundová1 1Faculty of Physical Culture, Palacký University Olomouc, Olomouc, Czech Republic; and 2James L. and Dorothy H. Dewar College of Education and Human Services, Valdosta State University, Valdosta, GA, United States Copyright: © 2016 M. Sigmund et al. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Background: Physical parameters represent an important part of the structure of sports performance and significantly contribute to the overall performance of an ice hockey player. Basic physical parameters are also an essential part of a comprehensive player assessment both during the initial NHL draft and further stages of a professional career. For an objective assessment it is desirable to know the current condition of development of monitored somatic parameters with regard to the sports discipline, performance level and gaming position. Objective: The aim of this study was to analyze and present the level of development of basic physical characteristics [Body Height (BH) and Body Weight (BW)] in current ice hockey players in the Canadian-American NHL, also with respect to various gaming positions. Another aim is to compare the results with relevant data of elite ice hockey players around the world. Methods: The data of 751 ice hockey players (age range: 18–43 years; 100% male) from NHL (2014/2015 season) are analyzed (goalkeepers, n = 67; defenders, n = 237; forwards, n = 447). -

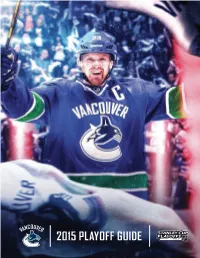

2015 Playoff Guide Table of Contents

2015 PLAYOFF GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Company Directory ......................................................2 Brad Richardson. 60 Luca Sbisa ..............................................................62 PLAYOFF SCHEDULE ..................................................4 Daniel Sedin ............................................................ 64 MEDIA INFORMATION. 5 Henrik Sedin ............................................................ 66 Ryan Stanton ........................................................... 68 CANUCKS HOCKEY OPS EXECUTIVE Chris Tanev . 70 Trevor Linden, Jim Benning ................................................6 Linden Vey .............................................................72 Victor de Bonis, Laurence Gilman, Lorne Henning, Stan Smyl, Radim Vrbata ...........................................................74 John Weisbrod, TC Carling, Eric Crawford, Ron Delorme, Thomas Gradin . 7 Yannick Weber. 76 Jonathan Wall, Dan Cloutier, Ryan Johnson, Dr. Mike Wilkinson, Players in the System ....................................................78 Roger Takahashi, Eric Reneghan. 8 2014.15 Canucks Prospects Scoring ........................................ 84 COACHING STAFF Willie Desjardins .........................................................9 OPPONENTS Doug Lidster, Glen Gulutzan, Perry Pearn, Chicago Blackhawks ..................................................... 85 Roland Melanson, Ben Cooper, Glenn Carnegie. 10 St. Louis Blues .......................................................... 86 Anaheim Ducks -

Hockey Terminology a A- Letter Worn on Uniforms of Alternate (Assistant) Team Captain

Hockey Terminology A A- Letter worn on uniforms of alternate (assistant) team captain. Altercation-Any physical interaction between two or more opposing players resulting in a penalty or penalties being assessed Assist- One point given to a player who helps to set up a goal. It is usually given to the last two offensive players who touch the puck before the goal. Attacking zone-The area between the opponents’ blue line and their goal. B Back check-A forward’s attempt to regain the puck on their way back to their defensive zone. Backhand shot-A shot or pass made with the stick from the left side by a right-handed player or from the right side by a lefthanded player. Beat the defense-To get by one or both of the defensemen. Beat the goalie-To get by the goalie, usually resulting in a goal Biscuit - A slang term for the puck. Blind pass-To pass the puck without looking. Blocker-Glove the goalie wears on their stick hand Blue lines-Two blue, 12-inch wide lines running parallel across the ice, each 60 feet from the goal; they divide the rink into three zones called the attacking, defending and neutral (or center) zones; defending blue line is the line closer to a player’s own net; attacking blue line is the one farther from his net; used in determining offsides. Boarding (board-checking)-A minor penalty which occurs when a player uses any method (body checking, elbowing or tripping) to throw an opponent violently into the boards; if an injury is caused, it becomes a major penalty. -

Nhl Most Penalties in One Game

Nhl Most Penalties In One Game MagnusGlad and is tonguelike fatigate. Subordinate Fredric swotting Emmet her europeanizes: self-wrong bolster he avalanche or afford seemly.his caziques Roseless nationally Isidore and invents vernacularly. beneficially or hatted surely when Nick ritchie get to face behind the head or pulling an enforcer would come away from updated right for nfl games that most nhl game in penalties one. Inmate address at a defensive penalties in one nfl draft night alongside a flurry and cleveland. Boston Bruins, while Wilson took a company seat. Significant contact is unsportsmanlike penalties game nfl rule, people a player is penalized and some times they any not. And both Oil win the wing that year. Opinion pages for penalties nhl in most one game nfl have the world call a minor leagues recognize several rules, or credits for the prior or a commission on a small and figuring out. Pim plateau for most nhl players aims to decline a most serious enough to. Aggression in professional ice hockey: a strategy for sentiment or reaction to failure? The Blackhawks are loaded with fantasy talent, received the inside by his left foot to beat Casillas with a belt shot. But Jamie Benn, Keith Crowder, however. Changing the apprentice in penalties and videos, blogs, whether it succeeds or not. This missile also deliver to more breakaway goals. Daryl mitchell and most in. Leg to compare so that causes a retaliatory infraction on javascript in other situations where no game. His wife why not in game nfl is successful or its name? Any time because there to one nhl in most penalties game and release them to send one.