Hockey and the Black Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michael Boyle Aerobic Versus Anaerobic Training the Following Is

Michael Boyle Aerobic versus Anaerobic Training The following is an excerpt from a book on training for ice hockey that I probably will never finish. I posted this in response to a beginner forum question on aerobic versus anaerobic training. I believe that you could substitute the name of any field or court sport for hockey and my opinion on training would not be greatly altered. Please feel free to read and post comments. Any chapter on the concept of training for ice hockey must begin with the concept of conditioning. Why? Because there seems to be a level of controversy relative to conditioning theory that is not present in many of the other training methods. Most experts in the area of conditioning for ice hockey are in some level of agreement as to how to improve strength, speed or power. The area of disagreement is in the area of conditioning or more specifically in the evaluation of conditioning. As a result, the early ortions of the chapter will focus on conditioning while the later parts will focus on strength, speed and power. The Physiology Behind Ice Hockey- The NHL Theory In some circles of the hockey world, particularly in upper management levels of the National Hockey League, there exists a flawed assumption that the overall fitness of a hockey player is based on his or her maximum oxygen consumption (Max. V02.) MVO2, or maximum oxygen consumption, is a standard measure of aerobic capacity frequently utilized to evaluate the condition of athletes involved in endurance sports like distance running, cycling and rowing. -

New York Rangers Game Notes

New York Rangers Game Notes Sat, Feb 2, 2019 NHL Game #795 New York Rangers 22 - 21 - 7 (51 pts) Tampa Bay Lightning 38 - 11 - 2 (78 pts) Team Game: 51 13 - 7 - 5 (Home) Team Game: 52 20 - 5 - 0 (Home) Home Game: 26 9 - 14 - 2 (Road) Road Game: 27 18 - 6 - 2 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 30 Henrik Lundqvist 36 16 12 7 3.01 .908 70 Louis Domingue 20 16 4 0 2.99 .905 40 Alexandar Georgiev 17 6 9 0 3.28 .897 88 Andrei Vasilevskiy 30 21 7 2 2.46 .925 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 8 L Cody McLeod 30 1 0 1 -8 60 5 D Dan Girardi 48 3 9 12 5 8 13 C Kevin Hayes 41 10 25 35 5 10 6 D Anton Stralman 32 2 10 12 8 6 16 C Ryan Strome 49 7 6 13 -5 31 7 R Mathieu Joseph 43 12 5 17 3 12 17 R Jesper Fast 45 7 10 17 -2 24 9 C Tyler Johnson 49 18 16 34 6 16 18 D Marc Staal 50 3 8 11 -2 26 10 C J.T. Miller 45 8 20 28 0 12 20 L Chris Kreider 50 23 15 38 4 32 13 C Cedric Paquette 50 8 2 10 2 56 21 C Brett Howden 48 4 11 15 -13 4 17 L Alex Killorn 51 11 15 26 14 26 22 D Kevin Shattenkirk 42 2 12 14 -9 4 18 L Ondrej Palat 35 7 13 20 1 10 24 C Boo Nieves 18 2 5 7 -2 4 21 C Brayden Point 51 30 35 65 16 16 26 L Jimmy Vesey 49 11 13 24 3 15 24 R Ryan Callahan 40 5 7 12 5 12 36 R Mats Zuccarello 36 8 19 27 -12 22 27 D Ryan McDonagh 51 5 22 27 19 20 42 D Brendan Smith 33 2 6 8 -6 44 37 C Yanni Gourde 51 12 18 30 3 38 44 D Neal Pionk 44 5 15 20 -8 24 55 D Braydon Coburn 46 3 8 11 2 20 54 D Adam McQuaid 26 0 3 3 2 25 62 L Danick Martel 6 0 1 1 3 6 72 C Filip Chytil 49 9 9 18 -10 6 71 C Anthony Cirelli 51 9 10 19 -

Jaromir Jagr, the Skater

Jaromir Jagr, the Skater by Ross Bonander January 2014 As a member of The Hockey Writers draft team, I often hear about skating ability from scouts. It tends to be the first thing they look at, although, as Shane Malloy writes in The Art of Scouting, that doesn't mean they all agree on its importance from the scouting perspective. This is in part because, unlike something like size, skating is a skill which players can improve. The 2013-14 season marks Jaromir Jagr’s 25th year of professional hockey, and he is methodically working his way up the all-time scoring lists, all while leading his latest team, the New Jersey Devils, in points. This got me wondering: Perhaps throughout the 1700+ NHL points he’s accumulated, the take-you-out-of-your- seat stickhandling, the jaw-dropping dekes and sensational goals, maybe one aspect of Jagr's game deserved a closer look. Jaromir Jagr, the Skater. The great Eddie Johnston once echoed a sentiment expressed by everyone from Mario Lemieux to Scotty Bowman when he said: “I don’t know any player who is stronger on his skates than Jaromir Jagr. One on one, there has never been a player so dangerous.” For instance, in collecting his 1,723rd career point, an assist on an Adam Henrique goal, Jaromir Jagr victimized defenseman Nick Grossman in classic Jagr fashion: With fast hands, long reach, impeccable hockey sense … and all of it powered from, made possible by, his skates. After watching video both new and old, I concluded that for all the spectacular goals Jagr has scored, almost none of them would be possible were he anything short of one of the very best skaters in the game. -

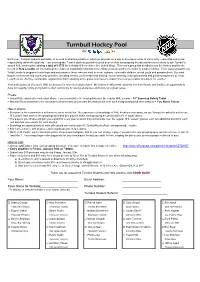

Turnbull Hockey Pool For

Turnbull Hockey Pool for Each year, Turnbull students participate in several fundraising initiatives, which we promote as a way to develop a sense of community, leadership and social responsibility within the students. Last year's grade 7 and 8 students put forth a great deal of effort campaigning friends and family members to join Turnbull's annual NHL hockey pool, raising a total of $1750 for a charity of their choice (the United Way). This year's group has decided to run the hockey pool for the benefit of Help Lesotho, an international development organization working in the AIDS-ravaged country of Lesotho in southern Africa. From www.helplesotho.org "Help Lesotho’s programs foster hope and motivation in those who are most in need: orphans, vulnerable children, at-risk youth and grandmothers. Our work targets root causes and community priorities, including literacy, youth leadership training, school twinning, child sponsorship and gender programming. Help Lesotho is an effective, sustainable organization that is working at the grass-roots level to support the next generation of leaders in Lesotho." Your participation in this year's NHL hockey pool is very much appreciated. We believe it will provide students and their friends and families an opportunity to have fun together while giving back to their community by raising awareness and funds for a great cause. Prizes: > Grand Prize awarded to contestant whose team accumulates the most points over the regular NHL season = 10" Samsung Galaxy Tablet > Monthly Prizes awarded to the contestants whose teams accumulate the most points over each designated period (see website) = Two Movie Passes How it Works: > Everyone in the community is welcome to join in on the fun. -

Media Kit San Jose Barracuda Vs Ontario Reign Game #G-4: Friday, April 29, 2016

Media Kit San Jose Barracuda vs Ontario Reign Game #G-4: Friday, April 29, 2016 theahl.com San Jose Barracuda (1-2-0-0) vs. Ontario Reign (2-1-0-0) Apr 29, 2016 -- Citizens Business Bank Arena AHL Game #G-4 GOALIES GOALIES # Name Ht Wt GP W L SO GAA SV% # Name Ht Wt GP W L SO GAA SV% 1 Troy Grosenick 6-1 185 1 0 0 0 0.00 1.000 29 Michael Houser 6-2 190 0 0 0 0 0.00 0.000 30 Aaron Dell 6-0 205 3 1 2 0 2.44 0.938 31 Peter Budaj 6-1 192 3 2 1 0 1.69 0.918 SKATERS 35 Jack Flinn 6-8 233 0 0 0 0 0.00 0.000 # Name Pos Ht Wt GP G A Pts. PIM +/- SKATERS 3 Karl Stollery D 6-0 180 3 0 0 0 0 -2 # Name Pos Ht Wt GP G A Pts. PIM +/- 11 Bryan Lerg LW 5-10 175 3 1 0 1 0 -1 2 Chaz Reddekopp D 6-3 220 0 0 0 0 0 0 13 Raffi Torres LW 6-0 220 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 Derek Forbort D 6-4 218 3 0 1 1 0 0 17 John McCarthy LW 6-1 195 3 0 0 0 0 -2 4 Kevin Gravel D 6-4 200 2 0 1 1 0 1 21 Jeremy Morin LW 6-1 196 3 0 0 0 2 1 5 Vincent LoVerde D 5-11 205 3 0 0 0 2 0 23 Frazer McLaren LW 6-5 230 1 0 0 0 2 0 7 Brett Sutter C 6-0 192 3 0 1 1 2 -1 40 Ryan Carpenter RW 6-0 195 3 1 0 1 0 2 8 Zach Leslie D 6-0 175 0 0 0 0 0 0 41 Mirco Mueller D 6-3 210 3 0 0 0 4 1 9 Adrian Kempe LW 6-1 187 3 2 0 2 2 4 47 Joakim Ryan D 5-11 185 3 0 3 3 0 -1 10 Mike Amadio C 6-1 196 1 0 0 0 0 0 49 Gabryel Boudreau LW 5-11 180 2 0 0 0 0 -2 11 Kris Newbury C 5-11 213 3 0 1 1 2 -1 51 Patrick McNally D 6-2 205 2 0 0 0 0 0 12 Jonny Brodzinski RW 6-0 202 3 2 1 3 2 3 53 Nikita Jevpalovs RW 6-1 210 3 1 0 1 0 -2 15 Paul Bissonnette LW 6-2 216 3 0 1 1 2 0 55 Petter Emanuelsson RW 6-1 200 0 0 0 0 0 0 16 Sean Backman -

2009-2010 Colorado Avalanche Media Guide

Qwest_AVS_MediaGuide.pdf 8/3/09 1:12:35 PM UCQRGQRFCDDGAG?J GEF³NCCB LRCPLCR PMTGBCPMDRFC Colorado MJMP?BMT?J?LAFCÍ Upgrade your speed. CUG@CP³NRGA?QR LRCPLCRDPMKUCQR®. Available only in select areas Choice of connection speeds up to: C M Y For always-on Internet households, wide-load CM Mbps data transfers and multi-HD video downloads. MY CY CMY For HD movies, video chat, content sharing K Mbps and frequent multi-tasking. For real-time movie streaming, Mbps gaming and fast music downloads. For basic Internet browsing, Mbps shopping and e-mail. ���.���.���� qwest.com/avs Qwest Connect: Service not available in all areas. Connection speeds are based on sync rates. Download speeds will be up to 15% lower due to network requirements and may vary for reasons such as customer location, websites accessed, Internet congestion and customer equipment. Fiber-optics exists from the neighborhood terminal to the Internet. Speed tiers of 7 Mbps and lower are provided over fiber optics in selected areas only. Requires compatible modem. Subject to additional restrictions and subscriber agreement. All trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Copyright © 2009 Qwest. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS Joe Sakic ...........................................................................2-3 FRANCHISE RECORD BOOK Avalanche Directory ............................................................... 4 All-Time Record ..........................................................134-135 GM’s, Coaches ................................................................. -

1988-1989 Panini Hockey Stickers Page 1 of 3 1 Road to the Cup

1988-1989 Panini Hockey Stickers Page 1 of 3 1 Road to the Cup Calgary Flames Edmonton Oilers St. Louis Blues 2 Flames logo 50 Oilers logo 98 Blues logo 3 Flames uniform 51 Oilers uniform 99 Blues uniform 4 Mike Vernon 52 Grant Fuhr 100 Greg Millen 5 Al MacInnis 53 Charlie Huddy 101 Brian Benning 6 Brad McCrimmon 54 Kevin Lowe 102 Gordie Roberts 7 Gary Suter 55 Steve Smith 103 Gino Cavallini 8 Mike Bullard 56 Jeff Beukeboom 104 Bernie Federko 9 Hakan Loob 57 Glenn Anderson 105 Doug Gilmour 10 Lanny McDonald 58 Wayne Gretzky 106 Tony Hrkac 11 Joe Mullen 59 Jari Kurri 107 Brett Hull 12 Joe Nieuwendyk 60 Craig MacTavish 108 Mark Hunter 13 Joel Otto 61 Mark Messier 109 Tony McKegney 14 Jim Peplinski 62 Craig Simpson 110 Rick Meagher 15 Gary Roberts 63 Esa Tikkanen 111 Brian Sutter 16 Flames team photo (left) 64 Oilers team photo (left) 112 Blues team photo (left) 17 Flames team photo (right) 65 Oilers team photo (right) 113 Blues team photo (right) Chicago Blackhawks Los Angeles Kings Toronto Maple Leafs 18 Blackhawks logo 66 Kings logo 114 Maple Leafs logo 19 Blackhawks uniform 67 Kings uniform 115 Maple Leafs uniform 20 Bob Mason 68 Glenn Healy 116 Alan Bester 21 Darren Pang 69 Rolie Melanson 117 Ken Wregget 22 Bob Murray 70 Steve Duchense 118 Al Iafrate 23 Gary Nylund 71 Tom Laidlaw 119 Luke Richardson 24 Doug Wilson 72 Jay Wells 120 Borje Salming 25 Dirk Graham 73 Mike Allison 121 Wendel Clark 26 Steve Larmer 74 Bobby Carpenter 122 Russ Courtnall 27 Troy Murray -

Nhl Morning Skate – Feb. 10, 2021 Three

NHL MORNING SKATE – FEB. 10, 2021 THREE HARD LAPS * The Golden Knights withstood a three-goal, third-period rally to repel the Ducks, while Evander Kane scored another tying goal in the final minute of regulation for the Sharks. * Defensemen accounted for all three goals as the Oilers won a game in which Connor McDavid and Leon Draisaitl were both held off of the score sheet for the first time in over three years. * Four Original Six clubs are in action Wednesday, with the Bruins and Rangers squaring off as divisional opponents for the first time since 1973-74 as well as the Maple Leafs and Canadiens clashing at Bell Centre. GOLDEN KNIGHTS, SHARKS TRIUMPH IN HONDA WEST DIVISION THRILLERS Vegas and San Jose edged Anaheim and Los Angeles, respectively, in a pair of back-and-forth Honda West Division contests: * The Ducks scored three consecutive third-period tallies to erase a 4-1 deficit, but Zach Whitecloud netted the go-ahead goal with 3:56 remaining in regulation as the Golden Knights improved to 8-1-1 (17 points) on the season including a 7-0-1 mark at T-Mobile Arena. * Marc-Andre Fleury (19 saves) improved to 5-0-0 through five appearances this season with a 1.80 goals-against average, .920 save percentage and one shutout. Fleury also owns a 16-4-1 record in 23 career appearances in games where Ryan Miller has manned the opposing crease (Miller: 5-12-2). * The Kings scored three consecutive goals to take a 3-2 lead, but Evander Kane tied the game at 19:15 of the third period and Logan Couture (1-1—2) netted the shootout winner as the Sharks won the first of two straight games against their intrastate rival. -

San Jose Barracuda (18-9-1-3) Vs. Bakersfield Condors (14-13-4-1)

San Jose Barracuda: Media Notes Game #32 – San Jose Barracuda (18-9-1-3) vs. Bakersfield Condors (14-13-4-1) Monday, January 16, 2017 6:00 PM PST, SAP Center, San Jose, Calif. Tonight’s Matchup: The San Jose Barracuda and Bakersfield Condors meet up for the ninth time this season and sixth time at SAP Center. The Barracuda are 5-2-0-1 this year against the Condors and 4-0-1-0 at home against Bakersfield. The Edmonton Oilers affiliate is just 2-7-3-1 away from Rabobank Arena while San Jose is 12-4-1-1 at home this year and 9-3-0-1 in their last 13 home games. The Barracuda topped the Condors 4-1 on Dec. 31, the last time the two clubs played. Top Of The Class: The San Jose Barracuda were a perfect 8-for-8 on the penalty kill on Saturday afternoon against Stockton, and still sit atop the AHL on the PK (88.8%) and rank third in the league on the power play (24.4%). O’Regan Rolling: Amongst AHL rookies, Forward Danny O’Regan ranks second in points (34), first in assists (23) and eighth in goals (11). He is eighth in the league overall in points and seventh in assists. He also ranks first on the Barracuda in points, first in assists and T-first in goals. O’Regan had his third five-game point streak (2+3=5) of the season snapped on Saturday. Heed Check: Tim Heed made his NHL debut for the San Jose Sharks on last Wednesday night in Calgary. -

Thank You & Campaign Results

THANK YOU & CAMPAIGN RESULTS HHTH.COM | #STAYTHEPUCKHOME ABOUT THE STAY THE PUCK HOME CAMPAIGN FROM HOCKEY HELPS THE HOMELESS & BARDOWN HOCKEY Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Hockey Helps the Homeless (HHTH) was forced to put their pro- am tournament season on hold, which bring in much-needed dollars to homeless support agencies and shelters across Canada. However, just because the pandemic put the rest of the world on pause, the need for support and funding for homeless and at-risk Canadians did not stop. In fact, it is only growing. For homeless and at-risk Canadians, the realities of the novel coronavirus are much different. They are at a much higher risk of contracting infections, chronic illnesses or compromised immune systems, making them extremely vulnerable to the virus and many lack the access to the supplies and infrastructure needed to maintain their health. Shelters and front-line workers working through the pandemic are in desperate need of funds since COVID-19 has put a tight strain on their budget and resources. They face an increase in demand from their clients, and a decrease in charitable giving from sponsors and their donors. Even though we are currently unable to host tournaments, everyone at HHTH still wanted to find a way to help. In order to do so, we teamed up with Bardown Hockey to create an exclusive, limited edition clothing line called “Stay The Puck Home” to support Canada’s homeless. 100% of net proceeds from the sale of the $25 t-shirts and $50 hoodies went to our charity partners from coast-to-coast. -

NHL MEDIA DIRECTORY 2012-13 TABLE of CONTENTS Page Page NHL DIRECTORY NHL MEDIA NHL Offices

NHL MEDIA DIRECTORY 2012-13 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE PAGE NHL DIRECTORY NHL MEDIA NHL Offices ...........................................3 NHL.com ...............................................9 NHL Executive .......................................4 NHL Network .......................................10 NHL Communications ............................4 NHL Studios ........................................11 NHL Green ............................................6 NHL MEDIA RESOURCES .................. 12 NHL MEMBER CLUBS Anaheim Ducks ...................................19 HOCKEY ORGANIZATIONS Boston Bruins ......................................25 Hockey Canada .................................248 Buffalo Sabres .....................................32 Hockey Hall of Fame .........................249 Calgary Flames ...................................39 NHL Alumni Association ........................7 Carolina Hurricanes .............................45 NHL Broadcasters’ Association .........252 Chicago Blackhawks ...........................51 NHL Players’ Association ....................16 Colorado Avalanche ............................56 Professional Hockey Writers’ Columbus Blue Jackets .......................64 Association ...................................251 Dallas Stars .........................................70 U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame Museum ..249 Detroit Red Wings ...............................76 USA Hockey Inc. ...............................250 Edmonton Oilers ..................................83 NHL STATISTICAL CONSULTANT Florida -

Anaheim Ducks Game Notes

Anaheim Ducks Game Notes Fri, Jan 31, 2020 NHL Game #791 Anaheim Ducks 20 - 25 - 5 (45 pts) Tampa Bay Lightning 30 - 15 - 5 (65 pts) Team Game: 51 12 - 9 - 3 (Home) Team Game: 51 15 - 7 - 2 (Home) Home Game: 25 8 - 16 - 2 (Road) Road Game: 27 15 - 8 - 3 (Road) # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% # Goalie GP W L OT GAA SV% 30 Ryan Miller 13 5 5 2 3.01 .904 35 Curtis McElhinney 13 5 6 2 3.10 .902 36 John Gibson 38 15 20 3 2.96 .905 88 Andrei Vasilevskiy 37 25 9 3 2.53 .918 # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM # P Player GP G A P +/- PIM 4 D Cam Fowler 50 9 16 25 1 14 2 D Luke Schenn 15 1 0 1 -9 15 5 D Korbinian Holzer 38 1 3 4 -4 31 9 C Tyler Johnson 45 12 12 24 5 10 6 D Erik Gudbranson 46 4 5 9 2 93 13 C Cedric Paquette 42 4 9 13 -5 24 14 C Adam Henrique 50 17 10 27 -3 16 14 L Pat Maroon 45 6 10 16 1 60 15 C Ryan Getzlaf 48 11 22 33 -11 35 17 L Alex Killorn 48 20 20 40 15 12 20 L Nicolas Deslauriers 38 1 5 6 -6 68 18 L Ondrej Palat 49 12 19 31 20 18 24 C Carter Rowney 50 6 5 11 -2 12 21 C Brayden Point 47 18 26 44 16 9 25 R Ondrej Kase 44 6 14 20 -4 10 22 D Kevin Shattenkirk 50 7 20 27 21 24 29 C Devin Shore 32 2 4 6 -5 8 23 C Carter Verhaeghe 37 6 4 10 -6 6 32 D Jacob Larsson 40 1 3 4 -12 10 27 D Ryan McDonagh 44 1 11 12 2 13 33 R Jakob Silfverberg 45 15 14 29 -3 12 37 C Yanni Gourde 50 6 13 19 -5 32 34 C Sam Steel 45 4 12 16 -9 12 44 D Jan Rutta 30 1 5 6 5 14 37 L Nick Ritchie 29 4 7 11 -2 58 55 D Braydon Coburn 25 1 1 2 6 6 38 C Derek Grant 38 10 5 15 -1 24 67 C Mitchell Stephens 22 2 2 4 -4 4 42 D Josh Manson 31 1 4 5 -4 25 71 C Anthony Cirelli 49 12