Spade Cultivation in Flanders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loy Real Estate and Auction

Loy Real Estate and Auction http://loyrealestateauction.com/ Auction Title : AL & JANET HUSTON Auction Date : MARCH 27, 2021 Auction Type : Antiques Bidding Start Time : 9:30am Bidding Location : Bubp Hall at Jay Co Fairgrounds Terms of Sale : Cash, check or Credit Card Sale Bill Category Heading 01 : ANTIQUES – OLD AND COLLECTORS ITEMS- GUNS - HOUSEHOLD Sale Bill Category Body 01 : Oak dry sink cabinet; Oak curved glass china cabinet; Oak roll top desk; Oak high boy dresser; Walnut tall ornate bed; Walnut wardrobe; Oak round table with 6 chairs; Oak sewing machine cabinet with sewing machine; (2) curio cabinets; Standard Oil double sided sign; Kendall Motor Oil double sided sign; Mail Pouch thermometer; Fairbanks Morse Scales porcelain sign; Oak wall telephone; Oak wall coat rack; Mersman drum table; Pineapple design pedestals; Ansonia clock; sugar shakers; hat pins; perfume bottles; Ohio Farms Ins Co 1924 statue; Indian statue; GUNS: Stevens Bicycle Rifle; Italy 50 cal black powder muzzle loader; muzzle loader; Phoenix 38 caliber; Stevens 22 caliber long rifle; 92 Winchester 25/20; Winchester Model 94 - 30/30; Stevens Rolling Block 22; Keystone 22 single shot long rifle; Marlin 22 S/L LR pump; cross bow; New Haven 1853 wall clock; knives; quilts; Harry Combs Insurance, Van Wert thermometer; coffee grinder; school bells; sweetheart oil lamps; banks; Sterling coasters; Mayonaisse churn; Berne Milling Co. advertisement; cuckoo clock; ST CLAIR: several paperweights along with a pair of bookends and doorstop; large assortment of pictures; -

Distribution and Ecology of the Stoneflies (Plecoptera) of Flanders

Ann. Limnol. - Int. J. Lim. 2008, 44 (3), 203 - 213 Distribution and ecology of the stonefl ies (Plecoptera) of Flanders (Belgium) K. Lock, P.L.M. Goethals Ghent University, Laboratory of Environmental Toxicology and Aquatic Ecology, J. Plateaustraat 22, 9000 Gent, Belgium. Based on a literature survey and the identifi cation of all available collection material from Flanders, a checklist is presented, distribution maps are plotted and the relationship between the occurrence of the different species and water characteristics is analysed. Of the sixteen stonefl y species that have been recorded, three are now extinct in Flanders (Isogenus nubecula, Taen- iopteryx nebulosa and T. schoenemundi), while the remaining species are rare. The occurrence of stonefl ies is almost restricted to small brooks, while observations in larger watercourses are almost lacking. Although a few records may indicate that some larger watercourses have recently been recolonised, these observations consisted of single specimens and might be due to drift. Most stonefl y population are strongly isolated and therefore extremely vulnerable. Small brooks in the Campine region (northeast Flanders), which are characterised by a lower pH and a lower conductivity, contained a different stonefl y community than the small brooks in the rest of Flanders. Leuctra pseudosignifera, Nemoura marginata and Protonemura intricata are mainly found in small brooks in the loamy region, Amphinemura standfussi, Isoperla grammatica, Leuctra fusca, L. hippopus, N. avicularis and P. meyeri mainly occur in small Campine brooks, while L. nigra, N. cinerea and Nemurella pictetii can be found in both types. Nemoura dubitans can typically be found in stagnant water fed with freatic water. -

State of Play Analyses for Antwerp & Limburg- Belgium

State of play analyses for Antwerp & Limburg- Belgium Contents Socio-economic characterization of the region ................................................................ 2 General ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Hydrology .................................................................................................................................. 7 Regulatory and institutional framework ......................................................................... 11 Legal framework ...................................................................................................................... 11 Standards ................................................................................................................................ 12 Identification of key actors .............................................................................................. 13 Existing situation of wastewater treatment and agriculture .......................................... 17 Characterization of wastewater treatment sector ................................................................. 17 Characterization of the agricultural sector: ............................................................................ 20 Existing related initiatives ................................................................................................ 26 Discussion and conclusion remarks ................................................................................ -

PDF Viewing Archiving 300

Mémoires pour servir à l'Explication Toelichtende Verhandelingen des Cartes Géologiques et Minières voorde Geologische en Mijnkaarten de la Belgique van België Mémoire No 21 Verhandeling N° 21 Subsurface structural analysis of the late-Dinantian carbonate shelf at the northern flank of the Brabant Massif (Campine Basin, N-Belgium). by R. DREESEN, J. BOUCKAERT, M. DUSAR, J. SOl LLE & N. VANDENBERGHE MINISTERE DES AFFAIRES ECONOMIQUES MINISTERIE VAN ECONOMISCHE ZAKEN ADMINISTRATION DES MINES BESTUUR VAN HET MIJNWEZEN Service Géologique de Belgique Belgische Geologische Dienst 13, rue Jenner 13,Jennerstr.aat 1040 BRUXELLES 1040 BRUSSEL Mé~. Expl. Cartes Géologiques et Minières de la Belgique 1987 N° 21 37p. 18 fig. Toelicht. Verhand. Geologische en Mijnkaarten van België blz. tabl. SUBSURFACE STRUCTURAL ANAL VSIS OF THE LATE-DINANTIAN CARBONATE SHELF AT THE NORTHERN FLANK OF THE BRABANT MASSIF (CAMPINE BASIN, N-BELGIUM). 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. Seismic surveys in the Antwerp Campine area 1.2. Geological - stratigraph ical setting 1.3. Main results 2. THE DINANTIAN CARBONATE SUBCROP 2. 1. Sei smic character 2.2. General trends and anomalies 2.2.1. Western zone 2.2.2. Eastern zone 2.2.3. Transition zone 2.3. Deformations 2.3.1. Growth fault 2.3.2. Collapse structures 2.3.3. T ectonics 2.3.3.1. Graben faults 2.3.3.2. Central belt 2.4. 1nternal and underlying structures 2.4.1. 1nternal structures 2.4.2. Underlying deep reflectors 3. RELATIONSHIP WITH OVERLYING STRATA 3.1. Upper Carboniferous 3.1.1. Namurian 3.1.2. Westphalian 3.2. Mesozoicum 3.3. -

Loy Real Estate and Auction

Loy Real Estate and Auction http://loyrealestateauction.com/ Auction Title : RICHARD AND NILA LAWRENCE Auction Date : April 29, 2017 Auction Type : Farm Machinery/Tools Bidding Start Time : 10:00 A.M. Bidding Location : 5399 E 550 N Union City Indiana Terms of Sale : Cash/Check/Credit Card with 3% convenience fee Sale Bill Category Heading 01 : TRACTORS – FARM MACHINERY – TOOLS – OLD ITEMS Sale Bill Category Body 01 : 1940 Ford 9N wide front gas tractor with Kelly loader; Minneapolis Moline Z narrow front gas tractor; 1937 Farmall narrow front steel wheel gas tractor, Serial # T419888; Massey Harris 444 wide front end tractor with 1 rear hydro outlet, motor stuck – Serial # 70901; Belsaw buzz saw mill, Model M14/2598 WITH 40” blade; Galion 402 grader with H Farmall power unit; Case 1816 gas skid loader; New Holland 469 haybine; New Holland 269 baler; (2) 7’ New Idea trail type rakes; 40’ hay and grain elevator; (5) hay wagons; IH 11’ wheel disc; Dunham 7’ cultimulcher; Ferguson 3 pt – 6 ½’ disc with mud scraper; Ford 3 pt – 6’ flail mower; Ford 3 pt – 6’ rotary mower; Ford 3 pt – 5’ rotary mower, rough metal; IH mid mount flail mower; 3 pt grader box; 3 pt IMCO grader blade; 3 pt grader blade; bale spear bucket mount bale mover; Ford 3 pt hitch buzz saw with belt; 3 pt hitch post hole auger; Case/Massey tractor tires; IH rims; tractor buckets; universal heavy bucket; Case 530 and Case 580 back hoe buckets; wagon bed supplies; Case 580 – 24” back hoe bucket; Clark electric cement mixer; New Idea ground driven spreader; PTO generator on -

Terra Australis 30

terra australis 30 Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. Its subject is the settlement of the diverse environments in this isolated quarter of the globe by peoples who have maintained their discrete and traditional ways of life into the recent recorded or remembered past and at times into the observable present. Since the beginning of the series, the basic colour on the spine and cover has distinguished the regional distribution of topics as follows: ochre for Australia, green for New Guinea, red for South-East Asia and blue for the Pacific Islands. From 2001, issues with a gold spine will include conference proceedings, edited papers and monographs which in topic or desired format do not fit easily within the original arrangements. All volumes are numbered within the same series. List of volumes in Terra Australis Volume 1: Burrill Lake and Currarong: Coastal Sites in Southern New South Wales. R.J. Lampert (1971) Volume 2: Ol Tumbuna: Archaeological Excavations in the Eastern Central Highlands, Papua New Guinea. J.P. White (1972) Volume 3: New Guinea Stone Age Trade: The Geography and Ecology of Traffic in the Interior. I. Hughes (1977) Volume 4: Recent Prehistory in Southeast Papua. B. Egloff (1979) Volume 5: The Great Kartan Mystery. R. Lampert (1981) Volume 6: Early Man in North Queensland: Art and Archaeology in the Laura Area. A. Rosenfeld, D. Horton and J. Winter (1981) Volume 7: The Alligator Rivers: Prehistory and Ecology in Western Arnhem Land. -

Track Changes Version

Proposal new articles of association TRACK CHANGES VERSION CAMPINE Public limited liability company At Nijverheidsstraat 2, 2340 Beerse, VAT BE 0403.807.337 RLE Antwerp section Turnhout DRAFT COORDINATED ARTICLES OF ASSOCIATION OPTING INTO THE NEW BELGIAN CODE ON COMPANIES AND ASSOCIATION SECTION I : Legal Form, Name, Registered Office, PurposeObject , Term Article 1 : Legal form and Name The company has the form of a limited liability company ("naamloze vennootschap") , which appeals or has appealed to the public savings . Its name is “CAMPINE”. Article 2 : Registered office The registered office of the company is located at 2340 Beerse, Nijverheidsstraat 2. However, the board of directors can decide to transfer its registered office to any other city in the country. The board of directors can decide to establish where it deems useful, whether in Belgium or abroad, branches administration offices, subsidiaries, stocks, or agencies. The company's website is www.campine.com. The company’s email address is [email protected]. Article 3 : PurposeObject The purposeobject of the company is to exploit the hereafter-mentioned exploitations and all similar establishments, either by practicing a metal industry or an industry of chemical products, either by adding or establishing industries or branches of industries, and this in order to enhance their productivity or to improve their return or production. In particular, the company will concentrate on the recycling of lead and other metal fabrics. Overall, the company is allowed to execute these industrial, commercial or financial transactions, which are to develop or to favour its industrial or commercial activities. Consequently, the company is allowed to merge with similar Belgian or foreign companies, by inscribing, purchasing of securities, contributing in kind, waiving of rights, leasing or renting or else, taking interests in all existing or future companies relating directly or indirectly with its company purposeobject . -

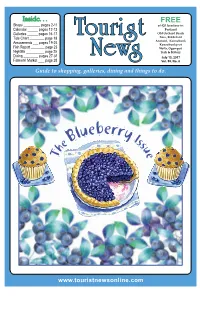

Lueberry Month, and Nowhere Is That More Relevant Than in the State of Maine

FREE Shops _________ pages 2-11 at 420 locations in: Calendar ______ pages 12-13 Portland Galleries _______ pages 16-17 Old Orchard Beach Tide Chart ________ page 18 Saco, Biddeford Amusements ___ pages 19-24 Arundel, Kennebunk Fish Report ________ page 23 Kennebunkport Inside. Wells, Ogunquit Nightlife __________ page 25 York & Kittery Dining ________ pages 27-31 July 13, 2017 Farmers' Market ___ page 28 Vol. 59, No. 8 Guide to shopping, galleries, dining and things to do. ueberry BTouril Ist e S su h e T NewS www.touristnewsonline.com PAGE 2 TOURIST NEWS, JUlLY 13, 2017 July is National Blueberry Month, and nowhere is that more relevant than in the state of Maine. Maine produces ATLANTIC TATOO COMPANY nearly 100 percent of the wild blueberries harvested an- nually in the United States. Custom Artwork Wild blueberries hold a special place in Maine’s agri- Professional cultural history – one that goes back centuries to Maine’s Piercing Native Americans who valued blueberries for their flavor, nutritional value and healing qualities. Route 1, Kennebunk In this issue of the Tourist News, we share some beside Dairy Queen blueberry history, tell you how to make some blueberry 207-985-4054 culinary treats and where you can pick your own berries. Savoring Wild Blueberries for Six Centuries by Dan Marois Wild blueberries hold a special place in Maine’s agricultural history – one that goes back centuries HEARTH & SOUL to Maine’s Native Ameri- cans. Native Americans Primarily Primitive were the first to use the Primitive Decor • Rugs • Old Village Paint tiny blue berries, both Shades • Candles • Pottery • Florals fresh and dried, for their flavor, nutrition and heal- ing qualities. -

Introduction Day To

BELGIAN BIKE TOURS - EMAIL: [email protected] - TELEPHONE +31(0)24-3244712 - FAX +31(0)24-3608454 - WWW.DUTCH-BIKETOURS.NL The Flemish Beer route 8 days, € 669 Introduction Belgium is famous worldwide for its many different beers, with a brewing tradition dating back to the Middle Ages. Centuries ago, even children were given a bit of brew to avoid the undependable drinking water. Nowadays over 200 breweries operate here, creating a variety of styles from refreshing white ale to bolder tripels and quadrupels. On this cycling holiday, discover the origin of several of Belgium’s best beers and marvel at the lovely surroundings that produce them! Pedal into woodlands in the Campine, roll past the renowned Achelse Kluis abbey and cross the Dutch border into Noord Brabant. Explore the world playing card capital of Turnhout and go mad in Antwerp trying to see everything on your list. The friendly university town of Leuven lives up to its reputation and your week ends with a fun and quirky highlight: cycling through water! Day to Day Day 1 Arrival Genk Make your way to Genk today, receive a friendly welcome at your hotel and wander through delightful Molenvijver Park before dinner. Day 2 Genk - Heeze 75 km Kick off your tour riding quiet roads to Bocholt, home to Europe’s largest beer brewery museum. Breathe in the aroma and discover the steps leading up to a perfectly poured pint. The nature reserve at Beverbeekse Heide is a world of wetlands, woods and patches of heath. Pause in Achelse Kluis to see the abbey and adjacent brewery, shop, gallery and inn. -

The Campine Plateau 12 Koen Beerten, Roland Dreesen, Jos Janssen and Dany Van Uytven

The Campine Plateau 12 Koen Beerten, Roland Dreesen, Jos Janssen and Dany Van Uytven Abstract Once occupied by shallow and wide braided channels of the Meuse and Rhine rivers around the Early to Middle Pleistocene transition, transporting and depositing debris from southern origin, the Campine Plateau became a positive relief as the combined result of uplift, the protective role of the sedimentary cover, and presumably also base level fluctuations. The escarpments bordering the Campine Plateau are tectonic or erosional in origin, showing characteristics of both a fault footwall in a graben system, a fluvial terrace, and a pediment. The intensive post-depositional evolution is attested by numerous traces of chemical and physical weathering during (warm) interglacials and glacials respectively. The unique interplay between tectonics, climate, and geomorphological processes led to the preservation of economically valuable natural resources, such as gravel, construction sand, and glass sand. Conversely, their extraction opened new windows onto the geological and geomorphological evolution of the Campine Plateau adding to the geoheritage potential of the first Belgian national park, the National Park Hoge Kempen. In this chapter, the origin and evolution of this particular landscape is explained and illustrated by several remarkable geomorphological highlights. Keywords Campine plateau Á Meuse terraces Á Late Glacial and Holocene dunes Á Tectonic control on fluvial evolution Á Polygonal soils Á Natural resources Á Coal mining 12.1 Introduction (TAW: Tweede Algemene Waterpassing) in the south, to ca. 30 m near the Belgian-Dutch border in the north (Fig. 12.1 The Campine Plateau is an extraordinary morphological b). The polygonal shape of this lowland plateau has attracted feature in northeastern Belgium, extending into the southern a lot of attention from geoscientists during the last 100 years, part of the Netherlands (Fig. -

2018 Natural Resources: an ASABE Global Initiative Conference

from the President ASABE at the World Food Prize, Ethical Dilemmas, and the Beauty of our Work n October, I had the honor of This issue of Resource contains an interesting juxtaposi- representing ASABE at the tion of content. ASABE’s annual recognition of outstanding Borlaug Dialogue. The high- new products, the AE50 Awards, highlights some of the latest Ilight was the awarding the 2017 advances in the food and agriculture industries. Many of World Food Prize to Dr. Akinwumi these products rely on software and electronic systems to Adesina, President of the African improve efficiency and productivity. Also in this issue is the Development Bank. Dr. Adesina, winning essay from the 2017 Ag & Bio Ethics Essay who holds a PhD in agricultural Competition for our pre-professional members. Amélie economics from Purdue University, Sirois-Leclerc of the University of Saskatchewan was the was recognized for aiding the small- winner with “Fighting the right to repair: The perpetuity of a scale farmers of Africa in general monopoly.” She argues for the right of equipment purchasers and Nigeria in particular. As to self-repair or use third-party services rather than be Nigeria’s Minister of Agriculture, required to use dealerships to obtain repairs. he introduced the E-Wallet system, which broke the back of The proliferation of computerized systems has created a corrupt elements that had controlled the fertilizer distribution significant issue. We used to think of agricultural machinery system for 40 years, demonstrating that access to technology as “big iron,” but today’s products are also “big silicon.” (cell phones and electronic commerce) can address long-stand- Maintaining the functionality of these increasingly software- ing challenges to food production and poverty. -

Physical Geography of North-Eastern Belgium - the Boom Clay Outcrop and Subcrop Zone

EXTERNAL REPORT SCK•CEN-ER-202 12/Kbe/P-2 Physical geography of north-eastern Belgium - the Boom Clay outcrop and subcrop zone Koen Beerten and Bertrand Leterme SCK•CEN Contract: CO-90-08-2214-00 NIRAS/ONDRAF contract: CCHO 2009- 0940000 Research Plan Geosynthesis November, 2012 SCK•CEN PAS Boeretang 200 BE-2400 Mol Belgium EXTERNAL REPORT OF THE BELGIAN NUCLEAR RESEARCH CENTRE SCK•CEN-ER-202 12/Kbe/P-2 Physical geography of north-eastern Belgium - the Boom Clay outcrop and subcrop zone Koen Beerten and Bertrand Leterme SCK•CEN Contract: CO-90-08-2214-00 NIRAS/ONDRAF contract: CCHO 2009- 0940000 Research Plan Geosynthesis January, 2012 Status: Unclassified ISSN 1782-2335 SCK•CEN Boeretang 200 BE-2400 Mol Belgium © SCK•CEN Studiecentrum voor Kernenergie Centre d’étude de l’énergie Nucléaire Boeretang 200 BE-2400 Mol Belgium Phone +32 14 33 21 11 Fax +32 14 31 50 21 http://www.sckcen.be Contact: Knowledge Centre [email protected] COPYRIGHT RULES All property rights and copyright are reserved to SCK•CEN. In case of a contractual arrangement with SCK•CEN, the use of this information by a Third Party, or for any purpose other than for which it is intended on the basis of the contract, is not authorized. With respect to any unauthorized use, SCK•CEN makes no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, and assumes no liability as to the completeness, accuracy or usefulness of the information contained in this document, or that its use may not infringe privately owned rights. SCK•CEN, Studiecentrum voor Kernenergie/Centre d'Etude de l'Energie Nucléaire Stichting van Openbaar Nut – Fondation d'Utilité Publique ‐ Foundation of Public Utility Registered Office: Avenue Herrmann Debroux 40 – BE‐1160 BRUSSEL Operational Office: Boeretang 200 – BE‐2400 MOL 5 Abstract The Boom Clay and Ypresian clays are considered in Belgium as potential host rocks for geological disposal of high-level and/or long-lived radioactive waste.