Changing Farming Methods in County Monaghan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loy Real Estate and Auction

Loy Real Estate and Auction http://loyrealestateauction.com/ Auction Title : AL & JANET HUSTON Auction Date : MARCH 27, 2021 Auction Type : Antiques Bidding Start Time : 9:30am Bidding Location : Bubp Hall at Jay Co Fairgrounds Terms of Sale : Cash, check or Credit Card Sale Bill Category Heading 01 : ANTIQUES – OLD AND COLLECTORS ITEMS- GUNS - HOUSEHOLD Sale Bill Category Body 01 : Oak dry sink cabinet; Oak curved glass china cabinet; Oak roll top desk; Oak high boy dresser; Walnut tall ornate bed; Walnut wardrobe; Oak round table with 6 chairs; Oak sewing machine cabinet with sewing machine; (2) curio cabinets; Standard Oil double sided sign; Kendall Motor Oil double sided sign; Mail Pouch thermometer; Fairbanks Morse Scales porcelain sign; Oak wall telephone; Oak wall coat rack; Mersman drum table; Pineapple design pedestals; Ansonia clock; sugar shakers; hat pins; perfume bottles; Ohio Farms Ins Co 1924 statue; Indian statue; GUNS: Stevens Bicycle Rifle; Italy 50 cal black powder muzzle loader; muzzle loader; Phoenix 38 caliber; Stevens 22 caliber long rifle; 92 Winchester 25/20; Winchester Model 94 - 30/30; Stevens Rolling Block 22; Keystone 22 single shot long rifle; Marlin 22 S/L LR pump; cross bow; New Haven 1853 wall clock; knives; quilts; Harry Combs Insurance, Van Wert thermometer; coffee grinder; school bells; sweetheart oil lamps; banks; Sterling coasters; Mayonaisse churn; Berne Milling Co. advertisement; cuckoo clock; ST CLAIR: several paperweights along with a pair of bookends and doorstop; large assortment of pictures; -

National University of Ireland Maynooth the ANCIENT ORDER

National University of Ireland Maynooth THE ANCIENT ORDER OF HIBERNIANS IN COUNTY MONAGHAN WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE PARISH OF AGHABOG FROM 1900 TO 1933 by SEAMUS McPHILLIPS IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF M.A. DEPARTMENT OF MODERN HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor R. V. Comerford Supervisor of Research: Dr. J. Hill July 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgement--------------------------------------------------------------------- iv Abbreviations---------------------------------------------------------------------------- vi Introduction----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 Chapter I The A.O.H. and the U.I.L. 1900 - 0 7 ------------------------------------43 Chapter II Death and destruction as home rule is denied 1908 - 21-------------81 Chapter III The A.O.H. in County Monaghan after partition 1922- 33 -------120 Conclusion-------------------------------------------------------------------------------143 ii FIGURES Figure 1 Lewis’s Map of 1837 showing Aghabog’s location in relation to County Monaghan------------------------------------------ 12 Figure 2 P. J. Duffy’s map of Aghabog parish showing the 68 townlands--------------------------------------------------13 Figure 3 P. J. Duffy’s map of the civil parishes of Clogher showing Aghabog in relation to the surrounding parishes-----------14 TABLES Table 1 Population and houses of Aghabog 1841 to 1911-------------------- 19 Illustrations------------------------------------------------------------------------------152 -

Annual Report 2019 Contents

Comhairle Contae Mhuineacháin Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2019 Monaghan County Council Annual Report 2019 Contents Foreword Page 2 – 3 District Map/Mission Statement Page 4 List of Members of Monaghan County Council 2019 Page 5 Finance Section Page 6 Corporate Services Page 7 – 9 Corporate Assets Page 10 – 13 Information Systems Page 13 – 15 Human Resources Page 16 – 17 Corporate Procurement Page 18 – 19 Health and Safety Page 19 – 20 The Municipal District of Castleblayney-Carrickmacross Page 21 – 24 The Municipal District of Ballybay-Clones Page 25 – 28 The Municipal District of Monaghan Page 29 – 33 Museum Page 34 – 35 Library Service Page 36 – 39 County Heritage Office Page 40 – 44 Arts Page 45 – 48 Tourism Page 48 – 51 Fire & Civil Protection Page 51 – 56 Water Services Page 56 – 62 Housing and Building Page 62 – 64 Planning Page 65 – 69 Environmental Protection Page 69 – 74 Roads and Transportation Page 74 – 76 Community Development Page 76 – 85 Local Enterprise Office Page 85 - 88 Strategic Policy Committee Updates Page 88 -89 Councillor Representations on External and Council Committees Page 90 -96 Conference Training attended by members Page 97 Appendix I - Members Expenses 2019 Page 98 – 99 Appendix II - Financial Statement 2019 Page 100 1 Foreword We welcome the publication of Monaghan County Council’s Annual Report for 2019. The annual report presents an opportunity to present the activities and achievements of Monaghan County Council in delivering public services and infrastructural projects during the year. Throughout 2019, Monaghan County Council provided high quality, sustainable public services aimed at enhancing the economic, environmental and cultural wellbeing of our people and county. -

Sustainable Management of Tourist Attractions in Ireland: the Development of a Generic Sustainable Management Checklist

SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF TOURIST ATTRACTIONS IN IRELAND: THE DEVELOPMENT OF A GENERIC SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT CHECKLIST By Caroline Gildea Supervised by Dr. James Hanrahan A dissertation submitted to the School of Business and Humanities, Institute of Technology, Sligo in fulfilment of the requirements of a Master of Arts (Research) June 2012 1 Declaration Declaration of ownership: I declare that this thesis is all my own work and that all sources used have been acknowledged. Signed: Date: 2 Abstract This thesis centres on the analysis of the sustainable management of visitor attractions in Ireland and the development of a tool to aid attraction managers to becoming sustainable tourism businesses. Attractions can be the focal point of a destination and it is important that they are sustainably managed to maintain future business. Fáilte Ireland has written an overview of the attractions sector in Ireland and discussed how they would drive best practice in the sector. However, there have still not been any sustainable management guidelines from Fáilte Ireland for tourist attractions in Ireland. The principal aims of this research was to assess tourism attractions in terms of water, energy, waste/recycling, monitoring, training, transportation, biodiversity, social/cultural sustainable management and economic sustainable management. A sustainable management checklist was then developed to aid attraction managers to sustainability within their attractions, thus saving money and the environment. Findings from this research concluded that tourism attractions in Ireland are not sustainably managed and there are no guidelines, training or funding in place to support these attraction managers in the transition to sustainability. Managers of attractions are not aware or knowledgeable enough in the area of sustainability. -

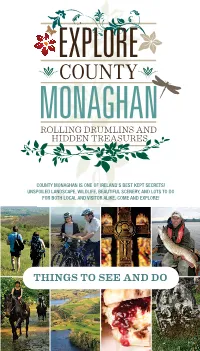

Things to See and Do Our Monaghan Story

COUNTY MONAGHAN IS ONE OF IRELAND'S BEST KEPT SECRETS! UNSPOILED LANDSCAPE, WILDLIFE, BEAUTIFUL SCENERY, AND LOTS TO DO FOR BOTH LOCAL AND VISITOR ALIKE. COME AND EXPLORE! THINGS TO SEE AND DO OUR MONAGHAN STORY OFTEN OVERLOOKED, COUNTY MONAGHAN’S VIBRANT LANDSCAPE - FULL OF GENTLE HILLS, GLISTENING LAKES AND SMALL IDYLLIC MARKET TOWNS - PROVIDES A TRUE GLIMPSE INTO IRISH RURAL LIFE. THE COUNTY IS WELL-KNOWN AS THE BIRTHPLACE OF THE POET PATRICK KAVANAGH AND THE IMAGES EVOKED BY HIS POEMS AND PROSE RELATE TO RURAL LIFE, RUN AT A SLOW PACE. THROUGHOUT MONAGHAN THERE ARE NO DRAMATIC VISUAL SHIFTS. NO TOWERING PEAKS, RAGGED CLIFFS OR EXPANSIVE LAKES. THIS IS AN AREA OFF THE WELL-BEATEN TOURIST TRAIL. A QUIET COUNTY WITH A SENSE OF AWAITING DISCOVERY… A PALPABLE FEELING OF GENUINE SURPRISE . HOWEVER, THERE’S A SIDE TO MONAGHAN THAT PACKS A LITTLE MORE PUNCH THAN THAT. HERE YOU WILL FIND A FRIENDLY ATMOSPHERE AND ACTIVITIES TO SUIT MOST INTERESTS WITH GLORIOUS GREENS FOR GOLFING , A HOST OF WATERSPORTS AND OUTDOOR PURSUITS AND A WEALTH OF HERITAGE SITES TO WHET YOUR APPETITE FOR ADVENTURE AND DISCOVERY. START BY TAKING A LOOK AT THIS BOOKLET AND GET EXPLORING! EXPLORE COUNTY MONAGHAN TO NORTH DONEGAL/DERRY AWOL Derrygorry / PAINTBALL Favour Royal BUSY BEE Forest Park CERAMICS STUDIO N2 MULLAN CARRICKROE CASTLE LESLIE ESTATE EMY LOUGH CASTLE LESLIE EQUESTRIAN CENTRE EMY LOUGH EMYVALE LOOPED WALK CLONCAW EQUESTRIAN CENTRE Bragan Scenic Area MULLAGHMORE EQUESTRIAN CENTRE GLASLOUGH TO ARMAGH KNOCKATALLON TYDAVNET CASTLE LESLIE TO BELFAST SLIABH BEAGH TOURISM CENTRE Hollywood Park R185 SCOTSTOWN COUNTY MUSEUM TYHOLLAND GARAGE THEATRE LEISURE CENTRE N12 RALLY SCHOOL MARKET HOUSE BALLINODE ARTS CENTRE R186 MONAGHAN VALLEY CLONES PEACE LINK MONAGHAN PITCH & PUTT SPORTS FACILITY MONAGHAN CLONES HERITAGE HERITAGE TRAIL TRAIL R187 5 N2 WILDLIFE ROSSMORE PARK & HERITAGE CLONES ULSTER ROSSMORE GOLF CLUB CANAL STORES AND SMITHBOROUGH CENTRE CARA ST. -

Loy Real Estate and Auction

Loy Real Estate and Auction http://loyrealestateauction.com/ Auction Title : RICHARD AND NILA LAWRENCE Auction Date : April 29, 2017 Auction Type : Farm Machinery/Tools Bidding Start Time : 10:00 A.M. Bidding Location : 5399 E 550 N Union City Indiana Terms of Sale : Cash/Check/Credit Card with 3% convenience fee Sale Bill Category Heading 01 : TRACTORS – FARM MACHINERY – TOOLS – OLD ITEMS Sale Bill Category Body 01 : 1940 Ford 9N wide front gas tractor with Kelly loader; Minneapolis Moline Z narrow front gas tractor; 1937 Farmall narrow front steel wheel gas tractor, Serial # T419888; Massey Harris 444 wide front end tractor with 1 rear hydro outlet, motor stuck – Serial # 70901; Belsaw buzz saw mill, Model M14/2598 WITH 40” blade; Galion 402 grader with H Farmall power unit; Case 1816 gas skid loader; New Holland 469 haybine; New Holland 269 baler; (2) 7’ New Idea trail type rakes; 40’ hay and grain elevator; (5) hay wagons; IH 11’ wheel disc; Dunham 7’ cultimulcher; Ferguson 3 pt – 6 ½’ disc with mud scraper; Ford 3 pt – 6’ flail mower; Ford 3 pt – 6’ rotary mower; Ford 3 pt – 5’ rotary mower, rough metal; IH mid mount flail mower; 3 pt grader box; 3 pt IMCO grader blade; 3 pt grader blade; bale spear bucket mount bale mover; Ford 3 pt hitch buzz saw with belt; 3 pt hitch post hole auger; Case/Massey tractor tires; IH rims; tractor buckets; universal heavy bucket; Case 530 and Case 580 back hoe buckets; wagon bed supplies; Case 580 – 24” back hoe bucket; Clark electric cement mixer; New Idea ground driven spreader; PTO generator on -

Peter Sweetman & Associates Rossport South Ballina

PETER SWEETMAN & ASSOCIATES ROSSPORT SOUTH ., a* .-> I . BALLINA " COUNTY MAYO [email protected], ~ :I "< ,d ', !G : ' Environmental Protection Agency Johnstown Castle .. Wexford ,, 2014-05-13 i ' : 1 Submission RE; I P0408- Carrickboy Farms, Ballyglassi'n, Edgeworthstown, Mr Dona1 Brady 02 Co. Longford. P0422- Silver Hill.Foods Hillcrest, Emyvale, County Monaghan. 03 I P0837- F. OHarte Poultry Creevaghy, Clones, County Monaghan. 02 Limited f ,I I. P0857- JPH Enterprises Quiglough, Ballinode, County Monaghan. 02 Limited , For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. ,I I, P0862- Mr James McGuirk Tetoppa, Dunraymond, County Monaghan. 02 P0923- Mi Paraig Kiely Carrowhauny, Ballyhaunis, Co. Mayo. 01 I P0929- Mr Pat Kenny Coolanoran, Newcastle West, Co. Limerick. 01 P0930- Mr Francis McCluskey Drumully, Smithboro, Co. Monaghan. 01 "I P0937- ? Mr Damien Treanor Killnagullan, Emyvale, County Monaghan. 01 PO95 1- Mr Dermot Crinion Dowth, Slane, County Meath. 01 II 1 EPA Export 01-09-2015:23:34:12 .. '0956- vir John McCabe Brandrum, Monaghan, County Monaghan. 11 rankerstown Pig & '0965- :arm Enterprises rankerstown, Bansha, Tipperary, County Tipperary. I1 Limited PO97 1- Martin and Mhairi Barnagurry, Kiltimagh, County Mayo. I1 Iempsey ~ P0972- I.M.K. Pigs Limited Lacklom & Ballintra, Inniskeen, County Monaghan. 31 P0975- Zlondrisse Pig Farm Joristown Upper, Killucan, County Westmeath. D1 Limited P0976- Senark Farm Limited Aghnaglough, Stranooden, County Monaghan. 02 P0979- Thomas & Trevor Ballyharrahan, Ring, CO Waterford. 0 1. Galvin , PO98 1- DIN0 Trading Limited Levalley, Ballinrobe, COMayo. 01 /I P0982- I Mr Don French Cloonee, Durrus, County Cork. 01 P0984- Clondrisse Pig Farm Bracklyn, Delvin, County Westmeath. 01 Limited ~ ,. -

Monaghan County Museum Events 2016

Monaghan comhaltas January Friday March 11th 7:30pm Launch of ‘a Fist to the Black Blooded’ by Hugh MacMahon Friday 29th 7pm This wonderful new book tells the Come and join Monaghan Comhaltas for a great night of story of three members of a County craic agus ceoil to celebrate Seachtain na Gaeilge. Monaghan family who were drawn into the 1916 Rising. FeBruary Last chance to see our fascinating exhibition ‘World Within Walls’ Tuesday 16th This exhibition explores the history of St Davnet’s Mental conservation Techniques Hospital, formerly known as the Tuesday 22nd 11am – 5pm Cavan & Monaghan Lunatic A paper conservation specialist will give a presentation Asylum. showing how museum objects such as estate maps are restored and stabilised for posterity. This will include MarcH examples of items from the museum collection. Booking essential Launch of “From a Whisper to a roar – exploring the untold Story of Monaghan easter arts & crafts Wednesday 23rd 10am – 12pm & 1.30pm – 3.30pm 1916” exhibition –Thursday 10th 7:30pm These fun workshops will give everyone the chance to Using rare imagery, objects and film, our 1916 make their own Easter artwork. Booking essential commemorative exhibition brings you back in time to a County Monaghan easter Treasure Hunt under British rule Thursday 24th 11.30am – 12.30pm & 2.30pm – 3.30pm where the whisper Bring the family along to enjoy this fun treasure hunt of an Irish Republic around the museum displays in search of those elusive exploded into a Easter Eggs. Booking essential roar after the 1916 Rising. Developed in partnership with apriL Professor Terence “Women of 1916” by Dr Mary Mcauliffe Dooley, NUI Thursday 21st 8pm Maynooth, who Dr Mary McAuliffe is a Teaching and Research Fellow in has written and Women’s Studies at the UCD School of Social Justice. -

Terra Australis 30

terra australis 30 Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. Its subject is the settlement of the diverse environments in this isolated quarter of the globe by peoples who have maintained their discrete and traditional ways of life into the recent recorded or remembered past and at times into the observable present. Since the beginning of the series, the basic colour on the spine and cover has distinguished the regional distribution of topics as follows: ochre for Australia, green for New Guinea, red for South-East Asia and blue for the Pacific Islands. From 2001, issues with a gold spine will include conference proceedings, edited papers and monographs which in topic or desired format do not fit easily within the original arrangements. All volumes are numbered within the same series. List of volumes in Terra Australis Volume 1: Burrill Lake and Currarong: Coastal Sites in Southern New South Wales. R.J. Lampert (1971) Volume 2: Ol Tumbuna: Archaeological Excavations in the Eastern Central Highlands, Papua New Guinea. J.P. White (1972) Volume 3: New Guinea Stone Age Trade: The Geography and Ecology of Traffic in the Interior. I. Hughes (1977) Volume 4: Recent Prehistory in Southeast Papua. B. Egloff (1979) Volume 5: The Great Kartan Mystery. R. Lampert (1981) Volume 6: Early Man in North Queensland: Art and Archaeology in the Laura Area. A. Rosenfeld, D. Horton and J. Winter (1981) Volume 7: The Alligator Rivers: Prehistory and Ecology in Western Arnhem Land. -

Lueberry Month, and Nowhere Is That More Relevant Than in the State of Maine

FREE Shops _________ pages 2-11 at 420 locations in: Calendar ______ pages 12-13 Portland Galleries _______ pages 16-17 Old Orchard Beach Tide Chart ________ page 18 Saco, Biddeford Amusements ___ pages 19-24 Arundel, Kennebunk Fish Report ________ page 23 Kennebunkport Inside. Wells, Ogunquit Nightlife __________ page 25 York & Kittery Dining ________ pages 27-31 July 13, 2017 Farmers' Market ___ page 28 Vol. 59, No. 8 Guide to shopping, galleries, dining and things to do. ueberry BTouril Ist e S su h e T NewS www.touristnewsonline.com PAGE 2 TOURIST NEWS, JUlLY 13, 2017 July is National Blueberry Month, and nowhere is that more relevant than in the state of Maine. Maine produces ATLANTIC TATOO COMPANY nearly 100 percent of the wild blueberries harvested an- nually in the United States. Custom Artwork Wild blueberries hold a special place in Maine’s agri- Professional cultural history – one that goes back centuries to Maine’s Piercing Native Americans who valued blueberries for their flavor, nutritional value and healing qualities. Route 1, Kennebunk In this issue of the Tourist News, we share some beside Dairy Queen blueberry history, tell you how to make some blueberry 207-985-4054 culinary treats and where you can pick your own berries. Savoring Wild Blueberries for Six Centuries by Dan Marois Wild blueberries hold a special place in Maine’s agricultural history – one that goes back centuries HEARTH & SOUL to Maine’s Native Ameri- cans. Native Americans Primarily Primitive were the first to use the Primitive Decor • Rugs • Old Village Paint tiny blue berries, both Shades • Candles • Pottery • Florals fresh and dried, for their flavor, nutrition and heal- ing qualities. -

2018 Natural Resources: an ASABE Global Initiative Conference

from the President ASABE at the World Food Prize, Ethical Dilemmas, and the Beauty of our Work n October, I had the honor of This issue of Resource contains an interesting juxtaposi- representing ASABE at the tion of content. ASABE’s annual recognition of outstanding Borlaug Dialogue. The high- new products, the AE50 Awards, highlights some of the latest Ilight was the awarding the 2017 advances in the food and agriculture industries. Many of World Food Prize to Dr. Akinwumi these products rely on software and electronic systems to Adesina, President of the African improve efficiency and productivity. Also in this issue is the Development Bank. Dr. Adesina, winning essay from the 2017 Ag & Bio Ethics Essay who holds a PhD in agricultural Competition for our pre-professional members. Amélie economics from Purdue University, Sirois-Leclerc of the University of Saskatchewan was the was recognized for aiding the small- winner with “Fighting the right to repair: The perpetuity of a scale farmers of Africa in general monopoly.” She argues for the right of equipment purchasers and Nigeria in particular. As to self-repair or use third-party services rather than be Nigeria’s Minister of Agriculture, required to use dealerships to obtain repairs. he introduced the E-Wallet system, which broke the back of The proliferation of computerized systems has created a corrupt elements that had controlled the fertilizer distribution significant issue. We used to think of agricultural machinery system for 40 years, demonstrating that access to technology as “big iron,” but today’s products are also “big silicon.” (cell phones and electronic commerce) can address long-stand- Maintaining the functionality of these increasingly software- ing challenges to food production and poverty. -

Curriculum Vitae of Claire Halpin

CURRICULUM VITAE OF CLAIRE HALPIN NAME: Claire Halpin STUDIO ADDRESS: Talbot Gallery and Studios, 51 Talbot Street, Dublin 1 WEBSITE: http://clairehalpin2011.wordpress.com/ or www.clairehalpin.ie EMAIL: [email protected] MOBILE: 087 6579271 DATE OF BIRTH: 24 June 1973 PLACE OF BIRTH: Dublin. Ireland EDUCATION 1997-1998 Masters in Art and Design [Painting] Grays School of Art, R.G.U, Aberdeen, Scotland. 1992-1996 Advanced Diploma in Fine Art [Painting], Dublin Institute of Technology. 1991-1992 Certificate in Art and Design, Colaiste Dhulaigh, Dublin. SOLO EXHIBITIONS Sept 2019 Solo Exhibition (forthcoming), Olivier Cornet Gallery, Dublin 2016 Glomar Response, Olivier Cornet Gallery, Dublin 2012 Reconstructions, Droichead Arts Centre, Drogheda. 2011 Reconstructions, Talbot Gallery, Dublin. Tabula Rasa, Cavan County Museum, Cavan 2010 Anaesthetic Aesthetics, RUA Red, South Dublin Arts Centre, Tallaght. 2008 Always Now, Talbot Gallery, Dublin. 2006 Eidetic Amalgams, Basement Gallery, Dundalk. 2004 Patina, Roscommon Arts Centre, Roscommon. 2001 Solo X 5, Model Arts Centre, Sligo. Engram Fragments, Triskel Arts Centre, Cork. 1999 Still, Monaghan County Museum and Gallery. Ingrained, Sligo Arts Festival, Sligo. RECENT SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2018 Savills Art Prize Shortlist, VUE Art Fair 2018, Royal Hibernian Academy, Dublin EVA International, Ireland's Biennial, Limerick City Gallery (Curator Inti Gurrero) Leinster Printmaking Exhibition, Kilcock Art Gallery, Kildare Cáirde Visual Sligo Arts Festival, The Model, Sligo. And the Women