National University of Ireland Maynooth the ANCIENT ORDER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A'railway Or Railways, Tr'araroad Or Trainroads, to Be Called the Dundalk Western Railway, from the Town of Dundalk in the Count

2411 a'railway or railways, tr'araroad or trainroads, to be den and Corrick iti the parish of Kilsherdncy in the* called the Dundalk Western Railway, from the town barony of Tullygarvy aforesaid, Killnacreena, Cor- of Dundalk in the county .of.Loiith to the town of nacarrew, Drumnaskey, Mullaghboy and Largy in Cavan, in the county of Cavan, and proper works, the parish of Ashfield in the barony of Tullygarvy piers, bridges; tunnels,, stations, wharfs and other aforesaid, Tullawella, Cornabest, Cornacarrew,, conveniences for the passage of coaches, waggons, Drumrane and Drumgallon in the parish of Drung and other, carriages properly adapted thereto, said in the barony of Tullygarvy aforesaid, Glynchgny railway or railways, tramway or tramways, com- or Carragh, Drumlane, Lisclone, Lisleagh, Lisha- mencing at or near the quay of Dundalk, in the thew, Curfyhone; Raskil and Drumneragh in the parish and town of Dundalk, and terminating at or parish of Laragh and barony of Tullygarvy afore- near the town of Cavan, in the county of Cavan, said, Cloneroy in the parish of Ballyhays in the ba- passing through and into the following townlands, rony of Upper Loughtee, Pottle Drumranghra, parishes, places, T and counties, viz. the town and Shankil, Killagawy, Billis, Strgillagh, Drumcarne,.- townlands of Dundalk, Farrendreg, and Newtoun Killynebba, Armaskerry, Drumalee, Killymooney Balregan, -in the parish of Gastletoun, and barony and Kynypottle in the parishes of Annagilliff and of Upper Dundalk, Lisnawillyin the parish of Dun- Armagh, barony of -

Camogie Association & GAA Information and Guidance Leaflet On

Camogie Association & GAA Information and Guidance leaflet on the National Vetting Bureau (Children & Vulnerable Persons) Act 2012 March 2015 1 National Vetting Bureau (Children & Vulnerable Persons) Act The National Vetting Bureau (Children and Vulnerable Persons) Act 2012 is the vetting legislation passed by the Houses of the Oireachtas in December 2012. This legislation is part of a suite of complementary legislative proposals to strengthen child protection policies and practices in Ireland. Once the ‘Vetting Bureau Act’ commences the law on vetting becomes formal and obligatory and all organisations and their volunteers or staff who with children and vulnerable adults will be legally obliged to have their personnel vetted. Such personnel must be vetted prior to the commencement of their work with their Association or Sports body. It is important to note that prior to the Act commencing that the Associations’ policy stated that all persons who in a role of responsibility work on our behalf with children and vulnerable adults has to be vetted. This applies to those who work with underage players. (The term ‘underage’ applies to any player who is under 18 yrs of age, regardless of what team with which they play). The introduction of compulsory vetting, on an All-Ireland scale through legislation, merely formalises our previous policies and practices. 1 When will the Act commence or come into operation? The Act is effectively agreed in law but has to be ‘commenced’ by the Minister for Justice and Equality who decides with his Departmental colleagues when best to commence all or parts of the legislation at any given time. -

A Seed Is Sown 1884-1900 (1) Before the GAA from the Earliest Times, The

A Seed is Sown 1884-1900 (1) Before the GAA From the earliest times, the people of Ireland, as of other countries throughout the known world, played ball games'. Games played with a ball and stick can be traced back to pre-Christian times in Greece, Egypt and other countries. In Irish legend, there is a reference to a hurling game as early as the second century B.C., while the Brehon laws of the preChristian era contained a number of provisions relating to hurling. In the Tales of the Red Branch, which cover the period around the time of the birth of Christ, one of the best-known stories is that of the young Setanta, who on his way from his home in Cooley in County Louth to the palace of his uncle, King Conor Mac Nessa, at Eamhain Macha in Armagh, practised with a bronze hurley and a silver ball. On arrival at the palace, he joined the one hundred and fifty boys of noble blood who were being trained there and outhurled them all single-handed. He got his name, Cuchulainn, when he killed the great hound of Culann, which guarded the palace, by driving his hurling ball through the hound's open mouth. From the time of Cuchulainn right up to the end of the eighteenth century hurling flourished throughout the country in spite of attempts made through the Statutes of Kilkenny (1367), the Statute of Galway (1527) and the Sunday Observance Act (1695) to suppress it. Particularly in Munster and some counties of Leinster, it remained strong in the first half of the nineteenth century. -

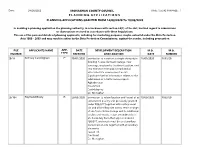

PLANNING APPLICATIONS GRANTED from 14/09/2020 to 18/09/2020

Date: 24/09/2020 MONAGHAN COUNTY COUNCIL TIME: 1:56:42 PM PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS GRANTED FROM 14/09/2020 To 18/09/2020 in deciding a planning application the planning authority, in accordance with section 34(3) of the Act, has had regard to submissions or observations recieved in accordance with these Regulations; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION M.O. M.O. NUMBER TYPE RECEIVED AND LOCATION DATE NUMBER 20/34 Anthony Cunningham P 30/01/2020 permission to construct a single storey style 16/09/2020 P855/20 dwelling house, domestic garage, new sewerage, wastewater treatment system, and new entrance onto public road and all associated site development works. Significant further information relates to the submission of a traffic survey report Aghadreenan Broomfield Castleblayney Co. Monaghan 20/104 Raymond Brady R 20/03/2020 permission to retain location and layout of as 18/09/2020 P863/20 constructed poultry unit previously granted under P08/627 together with vertical meal bin and all ancillary site works, retain change of use from nitrate storage unit to additional poultry unit on site, retain amendment's to site boundary from that approved under P08/627, and retain meal bin and ancillary store/shed on site together with all ancillary site works Tassan Td. -

Annual Report 2019 Contents

Comhairle Contae Mhuineacháin Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2019 Monaghan County Council Annual Report 2019 Contents Foreword Page 2 – 3 District Map/Mission Statement Page 4 List of Members of Monaghan County Council 2019 Page 5 Finance Section Page 6 Corporate Services Page 7 – 9 Corporate Assets Page 10 – 13 Information Systems Page 13 – 15 Human Resources Page 16 – 17 Corporate Procurement Page 18 – 19 Health and Safety Page 19 – 20 The Municipal District of Castleblayney-Carrickmacross Page 21 – 24 The Municipal District of Ballybay-Clones Page 25 – 28 The Municipal District of Monaghan Page 29 – 33 Museum Page 34 – 35 Library Service Page 36 – 39 County Heritage Office Page 40 – 44 Arts Page 45 – 48 Tourism Page 48 – 51 Fire & Civil Protection Page 51 – 56 Water Services Page 56 – 62 Housing and Building Page 62 – 64 Planning Page 65 – 69 Environmental Protection Page 69 – 74 Roads and Transportation Page 74 – 76 Community Development Page 76 – 85 Local Enterprise Office Page 85 - 88 Strategic Policy Committee Updates Page 88 -89 Councillor Representations on External and Council Committees Page 90 -96 Conference Training attended by members Page 97 Appendix I - Members Expenses 2019 Page 98 – 99 Appendix II - Financial Statement 2019 Page 100 1 Foreword We welcome the publication of Monaghan County Council’s Annual Report for 2019. The annual report presents an opportunity to present the activities and achievements of Monaghan County Council in delivering public services and infrastructural projects during the year. Throughout 2019, Monaghan County Council provided high quality, sustainable public services aimed at enhancing the economic, environmental and cultural wellbeing of our people and county. -

Sustainable Management of Tourist Attractions in Ireland: the Development of a Generic Sustainable Management Checklist

SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF TOURIST ATTRACTIONS IN IRELAND: THE DEVELOPMENT OF A GENERIC SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT CHECKLIST By Caroline Gildea Supervised by Dr. James Hanrahan A dissertation submitted to the School of Business and Humanities, Institute of Technology, Sligo in fulfilment of the requirements of a Master of Arts (Research) June 2012 1 Declaration Declaration of ownership: I declare that this thesis is all my own work and that all sources used have been acknowledged. Signed: Date: 2 Abstract This thesis centres on the analysis of the sustainable management of visitor attractions in Ireland and the development of a tool to aid attraction managers to becoming sustainable tourism businesses. Attractions can be the focal point of a destination and it is important that they are sustainably managed to maintain future business. Fáilte Ireland has written an overview of the attractions sector in Ireland and discussed how they would drive best practice in the sector. However, there have still not been any sustainable management guidelines from Fáilte Ireland for tourist attractions in Ireland. The principal aims of this research was to assess tourism attractions in terms of water, energy, waste/recycling, monitoring, training, transportation, biodiversity, social/cultural sustainable management and economic sustainable management. A sustainable management checklist was then developed to aid attraction managers to sustainability within their attractions, thus saving money and the environment. Findings from this research concluded that tourism attractions in Ireland are not sustainably managed and there are no guidelines, training or funding in place to support these attraction managers in the transition to sustainability. Managers of attractions are not aware or knowledgeable enough in the area of sustainability. -

Hard-Rock Mining, Labor Unions, and Irish Nationalism in the Mountain West and Idaho, 1850-1900

UNPOLISHED EMERALDS IN THE GEM STATE: HARD-ROCK MINING, LABOR UNIONS AND IRISH NATIONALISM IN THE MOUNTAIN WEST AND IDAHO, 1850-1900 by Victor D. Higgins A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University August 2017 © 2017 Victor D. Higgins ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Victor D. Higgins Thesis Title: Unpolished Emeralds in the Gem State: Hard-rock Mining, Labor Unions, and Irish Nationalism in the Mountain West and Idaho, 1850-1900 Date of Final Oral Examination: 16 June 2017 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Victor D. Higgins, and they evaluated his presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. John Bieter, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Jill K. Gill, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Raymond J. Krohn, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by John Bieter, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved by the Graduate College. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author appreciates all the assistance rendered by Boise State University faculty and staff, and the university’s Basque Studies Program. Also, the Idaho Military Museum, the Idaho State Archives, the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, and the Wallace District Mining Museum, all of whom helped immensely with research. And of course, Hunnybunny for all her support and patience. iv ABSTRACT Irish immigration to the United States, extant since the 1600s, exponentially increased during the Irish Great Famine of 1845-52. -

THE BELFAST GAZETTE, 23Rd DECEMBER, 1955

388 THE BELFAST GAZETTE, 23rd DECEMBER, 1955. IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE IN demands of which particulars shall have been given NORTHERN IRELAND as above required. QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION—IN BANKRUPTCY Dated this 20th day of December, 1955. J. D. DEVLIN, Solicitor for said Adminis- Thomas Adger and Frank Adger, trading as Adger trator, Cookstown. Bros, of West Drive, Portstewart, Co. London- derry, Builders, were on the 9th day of December, 1955, adjudged Bankrupts. STATUTORY NOTICE TO CREDITORS PUBLIC SITTINGS will be held before the In the Estate of James Austin, late of 15 Grand Court at the Royal Courts of Justice (Ulster), Parade, Belfast, Builder, deceased. Belfast, on Friday, the 13th day of January, 1956, NOTICE is hereby given, pursuant to the Statute and on Friday, the 20th day of January, 1956, at 22 and 23 Vic. Cap. 35, that all persons having the hour of Eleven o'clock in the forenoon, whereat any claims or demands against the Estate of the the Bankrupts are to attend, and to make a full above deceased, who died on the 24th day of disclosure and discovery of their Estate and Effects. January, 1955, are hereby required to furnish par- Creditors may prove their Debs, and at the First ticulars of such claims or demands (in writing) on Sitting choose a Creditors' Assignee. At the last or before the 1st day of March, 1956, to the under- Sitting the Bankrupts are required to finish their signed, Solicitors for the Administratrix, to whom Examination. Letters of Administration were on the 18th day of All persons having in their possession any May, 1955, granted forth of the Principal Registry Property of the Banrupts should deliver it and all of the Queen's Bench Division (Probate) of the Debts due to the Bankrupts should be paid to William High Court of Justice in Northern Ireland. -

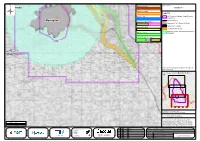

Monaghan Ballinode

Option A: Brown Figure Number Ballinode FIGURE 10.7 Option B: Orange Ü Legend Option C: Blue N2 Clontibret to Border Road Scheme Study Area National Border Monaghan Option D: Yellow + Pink E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E Monaghan CoCo Proposed Road E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E Settlement Envelope Option E: Yellow Local Area Action Plan Rural Area Under Strong Urban Influence Option F: Green (RAUSUI) Option G: Green + Yellow Threemilehouse Data source: Monaghan County Development Plan 2019-2025. ÜCounty Context Map (Not To Scale) M O N A G H A N Ordnance Survey Ireland 2018 © Ordnance Survey Ireland. All rights reserved. Licence number 2020/OSi_NMA_158 Monaghan County Council © Ordnance Survey Ireland. All rights reserved. Licence number 2020/30/CCMA/LouthCountyCouncil © Copyright 2020 Jacobs Engineering Ireland Limited. The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Jacobs. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of 0 0.5 1 2 Jacobs constitutes an infringement of copyright. -

Camphill Ballybay

Newsletter 2014 CAMPHILL BALLYBAY “ The healthy social life is found When in the mirror of each human soul The whole community finds its reflection And when in the community The virtue of each one is living ” CAMPHILL EVENTS LOOKING BACK, MOVING FORWARD What you see now as Camphill Community Ballybay is very very different than it was twenty one years FAMILY DAY ago. At that time the insight and determination of a small group of parents and friends from the locality brought about the small beginnings of a Camphill Community. This group raised a massive £50,000 to get the community started. It did not even start on the present site. The group of co-workers who pioneered the venture started out in a place called Nart. Afterwards they moved into the present site, which was given to Camphill by the Robb family, and they lived in Brighid House and Francis House, which were portocabin type buildings. Francis House was donated by Mourne Grange Community.Some people also lived in rented accommodation in Rockcorry, where the old Shirt Factory was, and there they had a Weavery,a Basket making workshop,and Candle making. Around this time, Glencraig Community donated Applegrove, another portocabin type house. The first building to go up in the community was the Hall. It could be divided in two by a curtain, and half was the Weavery and half was for gatherings, meetings, etc.Other projects around this time were an extension built on to Brighid House, the present Woodwork Shop, and the first farm building. It took a long time to get planning permission for Nuin House.It was built at last in 1996 and is a lovely example of a real Camphill house. -

Things to See and Do Our Monaghan Story

COUNTY MONAGHAN IS ONE OF IRELAND'S BEST KEPT SECRETS! UNSPOILED LANDSCAPE, WILDLIFE, BEAUTIFUL SCENERY, AND LOTS TO DO FOR BOTH LOCAL AND VISITOR ALIKE. COME AND EXPLORE! THINGS TO SEE AND DO OUR MONAGHAN STORY OFTEN OVERLOOKED, COUNTY MONAGHAN’S VIBRANT LANDSCAPE - FULL OF GENTLE HILLS, GLISTENING LAKES AND SMALL IDYLLIC MARKET TOWNS - PROVIDES A TRUE GLIMPSE INTO IRISH RURAL LIFE. THE COUNTY IS WELL-KNOWN AS THE BIRTHPLACE OF THE POET PATRICK KAVANAGH AND THE IMAGES EVOKED BY HIS POEMS AND PROSE RELATE TO RURAL LIFE, RUN AT A SLOW PACE. THROUGHOUT MONAGHAN THERE ARE NO DRAMATIC VISUAL SHIFTS. NO TOWERING PEAKS, RAGGED CLIFFS OR EXPANSIVE LAKES. THIS IS AN AREA OFF THE WELL-BEATEN TOURIST TRAIL. A QUIET COUNTY WITH A SENSE OF AWAITING DISCOVERY… A PALPABLE FEELING OF GENUINE SURPRISE . HOWEVER, THERE’S A SIDE TO MONAGHAN THAT PACKS A LITTLE MORE PUNCH THAN THAT. HERE YOU WILL FIND A FRIENDLY ATMOSPHERE AND ACTIVITIES TO SUIT MOST INTERESTS WITH GLORIOUS GREENS FOR GOLFING , A HOST OF WATERSPORTS AND OUTDOOR PURSUITS AND A WEALTH OF HERITAGE SITES TO WHET YOUR APPETITE FOR ADVENTURE AND DISCOVERY. START BY TAKING A LOOK AT THIS BOOKLET AND GET EXPLORING! EXPLORE COUNTY MONAGHAN TO NORTH DONEGAL/DERRY AWOL Derrygorry / PAINTBALL Favour Royal BUSY BEE Forest Park CERAMICS STUDIO N2 MULLAN CARRICKROE CASTLE LESLIE ESTATE EMY LOUGH CASTLE LESLIE EQUESTRIAN CENTRE EMY LOUGH EMYVALE LOOPED WALK CLONCAW EQUESTRIAN CENTRE Bragan Scenic Area MULLAGHMORE EQUESTRIAN CENTRE GLASLOUGH TO ARMAGH KNOCKATALLON TYDAVNET CASTLE LESLIE TO BELFAST SLIABH BEAGH TOURISM CENTRE Hollywood Park R185 SCOTSTOWN COUNTY MUSEUM TYHOLLAND GARAGE THEATRE LEISURE CENTRE N12 RALLY SCHOOL MARKET HOUSE BALLINODE ARTS CENTRE R186 MONAGHAN VALLEY CLONES PEACE LINK MONAGHAN PITCH & PUTT SPORTS FACILITY MONAGHAN CLONES HERITAGE HERITAGE TRAIL TRAIL R187 5 N2 WILDLIFE ROSSMORE PARK & HERITAGE CLONES ULSTER ROSSMORE GOLF CLUB CANAL STORES AND SMITHBOROUGH CENTRE CARA ST. -

Why Donegal Slept: the Development of Gaelic Games in Donegal, 1884-1934

WHY DONEGAL SLEPT: THE DEVELOPMENT OF GAELIC GAMES IN DONEGAL, 1884-1934 CONOR CURRAN B.ED., M.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR SPORTS HISTORY AND CULTURE AND THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORICAL AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES DE MONTFORT UNIVERSITY LEICESTER SUPERVISORS OF RESEARCH: FIRST SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR MATTHEW TAYLOR SECOND SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR MIKE CRONIN THIRD SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR RICHARD HOLT APRIL 2012 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements iii Abbreviations v Abstract vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Donegal and society, 1884-1934 27 Chapter 2 Sport in Donegal in the nineteenth century 58 Chapter 3 The failure of the GAA in Donegal, 1884-1905 104 Chapter 4 The development of the GAA in Donegal, 1905-1934 137 Chapter 5 The conflict between the GAA and association football in Donegal, 1905-1934 195 Chapter 6 The social background of the GAA 269 Conclusion 334 Appendices 352 Bibliography 371 ii Acknowledgements As a rather nervous schoolboy goalkeeper at the Ian Rush International soccer tournament in Wales in 1991, I was particularly aware of the fact that I came from a strong Gaelic football area and that there was only one other player from the south/south-west of the county in the Donegal under fourteen and under sixteen squads. In writing this thesis, I hope that I have, in some way, managed to explain the reasons for this cultural diversity. This thesis would not have been written without the assistance of my two supervisors, Professor Mike Cronin and Professor Matthew Taylor. Professor Cronin’s assistance and knowledge has transformed the way I think about history, society and sport while Professor Taylor’s expertise has also made me look at the writing of sports history and the development of society in a different way.