Susan Hegarty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inniskeen Spatial Plan DRAFT

Inniskeen Village Public Realm Spatial Plan (DRAFT) 12th Fenruary 2021 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Analysis 3. Concept 4. Key Spaces 5. Spatial Plan 6. Costs & Phasing Introduction Inniskeen Public Realm Spatial Plan has been prepared to inform the future development of public realm in and around Inniskeen for both locals and visitors alike. Spatial Plan Context Inniskeen is a small village located in Co.Monaghan, it is a historic settlement rich in archaeology, landscape features and architectural character, which inspired much of Patrick Kavanagh’s early work as a writer. There are two areas of commercial activity, at the road junction at McNello’s Pub which includes a public house, a petrol station, shop, and credit union. The second commercial centre is at the former railway station cluster including Magee’s public house and shop. Community uses dominate the centre of the village including the river walk, pitch and putt course, Community Centre, National School, Church of Ireland, Round Tower, Graveyard, and the Patrick Kavanagh Centre. Residential development occurs within the village centre to the north west and principally to the west of the village. Brief The Project Brief was to deliver a design which enhances the architectural quality of the sensitive streetscape, provides a high-quality concept and incorporates the following principles: • Reinvent the village as a place for people. • Development of pedestrian linkages between the Village, Kavanagh Centre and the Monaghan Way/ Railway Station. • Designation of key urban spaces for enhancement and specifi c urban design proposals. • Realisation of the potential of heritage and cultural assets for both locals and visitors. -

A'railway Or Railways, Tr'araroad Or Trainroads, to Be Called the Dundalk Western Railway, from the Town of Dundalk in the Count

2411 a'railway or railways, tr'araroad or trainroads, to be den and Corrick iti the parish of Kilsherdncy in the* called the Dundalk Western Railway, from the town barony of Tullygarvy aforesaid, Killnacreena, Cor- of Dundalk in the county .of.Loiith to the town of nacarrew, Drumnaskey, Mullaghboy and Largy in Cavan, in the county of Cavan, and proper works, the parish of Ashfield in the barony of Tullygarvy piers, bridges; tunnels,, stations, wharfs and other aforesaid, Tullawella, Cornabest, Cornacarrew,, conveniences for the passage of coaches, waggons, Drumrane and Drumgallon in the parish of Drung and other, carriages properly adapted thereto, said in the barony of Tullygarvy aforesaid, Glynchgny railway or railways, tramway or tramways, com- or Carragh, Drumlane, Lisclone, Lisleagh, Lisha- mencing at or near the quay of Dundalk, in the thew, Curfyhone; Raskil and Drumneragh in the parish and town of Dundalk, and terminating at or parish of Laragh and barony of Tullygarvy afore- near the town of Cavan, in the county of Cavan, said, Cloneroy in the parish of Ballyhays in the ba- passing through and into the following townlands, rony of Upper Loughtee, Pottle Drumranghra, parishes, places, T and counties, viz. the town and Shankil, Killagawy, Billis, Strgillagh, Drumcarne,.- townlands of Dundalk, Farrendreg, and Newtoun Killynebba, Armaskerry, Drumalee, Killymooney Balregan, -in the parish of Gastletoun, and barony and Kynypottle in the parishes of Annagilliff and of Upper Dundalk, Lisnawillyin the parish of Dun- Armagh, barony of -

Portfolio of Glaslough

An oasis of calm, where the hse is king GLASLOUGH CO MONAGHAN IRELAND INfORMAtION Q pORtfOLIO xxx ENtENtE fLORAL/E EUROpE 2017 CONtENtS foreword ...........................................................1 Beautiful Glaslough .......................................2 planning & Development ...........................3 Natural Environment ...................................5 Built Environment ..........................................7 Landscape ........................................................9 Green Spaces ..............................................10 planting ...........................................................13 Environmental Education ........................15 Effort & Involvement .................................17 tourism & Leisure .....................................18 Community ....................................................21 The Boathouse at Castle Leslie Estate. fOREwORD elcome to beautiful Glaslough, t is a very special privilege to welcome an oasis of calm tucked away the International Jury of Entente Florale Wbetween counties Monaghan, Ito Co. Monaghan to adjudicate Armagh and Tyrone. We were both thrilled Glaslough as one o@f Ireland’s and honoured to be nominated to representatives in this year’s competition. represent Ireland in this year’s Entente Co. Monaghan may not be one of the Florale competition. We hope to do better known tourist destinations of Ireland justice, and that you enjoy the best Ireland, but we are confident that after of scenery and hospitality during your stay spending a day -

National University of Ireland Maynooth the ANCIENT ORDER

National University of Ireland Maynooth THE ANCIENT ORDER OF HIBERNIANS IN COUNTY MONAGHAN WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE PARISH OF AGHABOG FROM 1900 TO 1933 by SEAMUS McPHILLIPS IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF M.A. DEPARTMENT OF MODERN HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor R. V. Comerford Supervisor of Research: Dr. J. Hill July 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgement--------------------------------------------------------------------- iv Abbreviations---------------------------------------------------------------------------- vi Introduction----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 Chapter I The A.O.H. and the U.I.L. 1900 - 0 7 ------------------------------------43 Chapter II Death and destruction as home rule is denied 1908 - 21-------------81 Chapter III The A.O.H. in County Monaghan after partition 1922- 33 -------120 Conclusion-------------------------------------------------------------------------------143 ii FIGURES Figure 1 Lewis’s Map of 1837 showing Aghabog’s location in relation to County Monaghan------------------------------------------ 12 Figure 2 P. J. Duffy’s map of Aghabog parish showing the 68 townlands--------------------------------------------------13 Figure 3 P. J. Duffy’s map of the civil parishes of Clogher showing Aghabog in relation to the surrounding parishes-----------14 TABLES Table 1 Population and houses of Aghabog 1841 to 1911-------------------- 19 Illustrations------------------------------------------------------------------------------152 -

Filming in Monaghan INTRODUCTION 1

Filming in Monaghan INTRODUCTION 1 A relatively undiscovered scenic location hub. Nestled among rolling drumlin landscape, with unspoilt rural scenery, and dotted with meandering rivers and lakes. Home to some of the most exquisite period homes, and ancient neolithic structures. Discover what Monaghan has to offer... CONTENTS 2 LANDSCAPES 3 BUILDINGS old & new 8 FORESTS and PARKS 15 RURAL TOWNS and VILLAGES 20 RIVERS and LAKES 25 PERIOD HOUSES 29 3 LANDSCAPES LANDSCAPES 4 Lough Muckno Ballybay Wetlands Sliabh Beagh LANDSCAPES 5 LANDSCAPES 6 Concra Wood Golf Club Rossmore Golf Club LANDSCAPES 7 Pontoon, Ballybay Wetlands Rossmore Forest Park 8 BUILDINGS old & new BUILDINGS old & new 9 Drumirren, Inniskeen Lisnadarragh Wedge Tomb Laragh Church Laragh Church Round Tower, Inniskeen BUILDINGS old & new 10 BUILDINGS old & new 11 Signal Box, Glaslough Famine Cottage, Brehon Brewhouse BUILDINGS old & new 12 Ulster Canal Stores Cassandra Hand Centre, Clones Courthouse, Monaghan Magheross Church Carrickmacross Workhouse Dartry Temple BUILDINGS old & new 13 Peace Link Clones Library Garage Theatre Peace Link Atheltic Track Ballybay Wetlands St. Macartans Cathedral, Monaghan BUILDINGS old & new 14 15 FORESTS and PARKS FORESTS and PARKS 16 Lough Muckno Rossmore Forest Park FORESTS and PARKS 17 Dartry Forest Lough Muckno Black Island FORESTS and PARKS 18 Rossmore Forest Park FORESTS and PARKS 19 BUILDINGS old & new 20 PERIOD HOUSES Castle Leslie Estate PERIOD HOUSES 21 Castle Leslie Estate PERIOD HOUSES 22 Hilton Park PERIOD HOUSES 23 Hilton Park PERIOD -

PLANNING APPLICATIONS GRANTED from 14/09/2020 to 18/09/2020

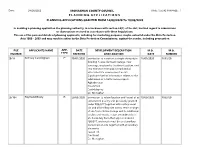

Date: 24/09/2020 MONAGHAN COUNTY COUNCIL TIME: 1:56:42 PM PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS GRANTED FROM 14/09/2020 To 18/09/2020 in deciding a planning application the planning authority, in accordance with section 34(3) of the Act, has had regard to submissions or observations recieved in accordance with these Regulations; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APPLICANTS NAME APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION M.O. M.O. NUMBER TYPE RECEIVED AND LOCATION DATE NUMBER 20/34 Anthony Cunningham P 30/01/2020 permission to construct a single storey style 16/09/2020 P855/20 dwelling house, domestic garage, new sewerage, wastewater treatment system, and new entrance onto public road and all associated site development works. Significant further information relates to the submission of a traffic survey report Aghadreenan Broomfield Castleblayney Co. Monaghan 20/104 Raymond Brady R 20/03/2020 permission to retain location and layout of as 18/09/2020 P863/20 constructed poultry unit previously granted under P08/627 together with vertical meal bin and all ancillary site works, retain change of use from nitrate storage unit to additional poultry unit on site, retain amendment's to site boundary from that approved under P08/627, and retain meal bin and ancillary store/shed on site together with all ancillary site works Tassan Td. -

St. Patrick and Louth Author(S): Lorcán P

County Louth Archaeological and History Society St. Patrick and Louth Author(s): Lorcán P. Ua Muireadhaigh Source: Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society, Vol. 2, No. 3 (Oct., 1910), pp. 213-236 Published by: County Louth Archaeological and History Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27727893 . Accessed: 14/06/2014 07:59 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. County Louth Archaeological and History Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 195.78.108.51 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 07:59:18 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 213 JOURNAL OF THE COUNTY LOUTH ARCH^OLOGICAL SOCIETY. No. 3. OCTOBER, 1910. Vol. II. g*t, Patrick cmfr goutty* 1. O thoroughly understand the different visits made by St. Patrick to Louth, a short sketch of the Saint's mission in Ireland is necessary. After landing in Strangford Lough in 432, Patrick preached for a while in Down and Antrim. In he sailed southwards, 433 " landed at the mouth of the Boyne, called at that time Inver Colpa/' and immediately directed his course towards Tara. -

Camphill Ballybay

Newsletter 2014 CAMPHILL BALLYBAY “ The healthy social life is found When in the mirror of each human soul The whole community finds its reflection And when in the community The virtue of each one is living ” CAMPHILL EVENTS LOOKING BACK, MOVING FORWARD What you see now as Camphill Community Ballybay is very very different than it was twenty one years FAMILY DAY ago. At that time the insight and determination of a small group of parents and friends from the locality brought about the small beginnings of a Camphill Community. This group raised a massive £50,000 to get the community started. It did not even start on the present site. The group of co-workers who pioneered the venture started out in a place called Nart. Afterwards they moved into the present site, which was given to Camphill by the Robb family, and they lived in Brighid House and Francis House, which were portocabin type buildings. Francis House was donated by Mourne Grange Community.Some people also lived in rented accommodation in Rockcorry, where the old Shirt Factory was, and there they had a Weavery,a Basket making workshop,and Candle making. Around this time, Glencraig Community donated Applegrove, another portocabin type house. The first building to go up in the community was the Hall. It could be divided in two by a curtain, and half was the Weavery and half was for gatherings, meetings, etc.Other projects around this time were an extension built on to Brighid House, the present Woodwork Shop, and the first farm building. It took a long time to get planning permission for Nuin House.It was built at last in 1996 and is a lovely example of a real Camphill house. -

File Number Monaghan County Council

DATE : 07/03/2019 MONAGHAN COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 14:25:50 PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 11/02/19 TO 15/02/19 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION EIS PROT. IPC WASTE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME TYPE RECEIVED RECD. STRU LIC. LIC. 19/60 Tiarnan Hand & Rebecca P 11/02/2019 permission for a single storey house, waste water Kenny treatment plant, a new site entrance and associated site works Drumass Inniskeen Co Monaghan 19/61 Norman Francey P 12/02/2019 permission to construct a new free range poultry unit, new litter store, roads underpass, hardened area, vertical meal bins, underground washings, tanks and all ancillary site works Corkish Td Newbliss Co Monaghan 19/62 Damien & Celina Babington P 12/02/2019 permission for a dwelling house, waste water treatment unit, and percolation area, & new entrance onto public road and all associated site works Drumcarrow Carrickmacross Co Monaghan 19/63 Paul & Emma Murphy P 12/02/2019 permission to erect a two storey extension to rear of existing dwelling and all associated site works. Raferagh Shercock Co Monaghan DATE : 07/03/2019 MONAGHAN COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 14:25:50 PAGE : 2 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 11/02/19 TO 15/02/19 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APP. -

The Municipal District of Carrickmacross – Castleblayney Monaghan County Council

Ceantar Bardasach Carraig Mhachaire Rois – Baile na Lorgan, Comhairle Contae Mhunieacháin The Municipal District of Carrickmacross – Castleblayney Monaghan County Council Minutes of proceedings of AGM of The Municipal District of Carrickmacross – Castleblayney Municipal District held in Carrickmacross Civic Offices, Riverside Road, Carrickmacross, on Friday 27th June 2014 @ 10.00 am. Present: Cllrs. Aidan Campbell, Jackie Crowe, Noel Keelan, Padraig McNally, PJ O’Hanlon, and Matt Carthy MEP Also in attendance:- Eugene Cummins, Chief Executive Monaghan County Council, Adge King, Director of Services, Cathal Flynn, Coordinator, Frances Matthews, Alan Hall, John Lennon, Joe Durnin, Mickey Duffy, Amanda Murray, Teresa McGuirk, Mary Marron, Stephanie McEneaney, Philomena Carroll Press – Veronica Corr, Northern Standard, Martin Shannon, Anglo Celt and Kieran Ward, Northern Sound Radio and Pat Byrne, photographer. Apologies - none Election of Cathaoirleach Cathal Flynn, Coordinator took the chair and welcomed all stating the AGM, represented a significant milestone in the history of local government for Carrickmacross and Castleblayney. Cllr Keelan welcomed coordinator and staff and wished well in their new roles. Cllr Keelan proposed Cllr Jackie Crowe for the position of Cathaoirleach. This was seconded by Cllr Aidan Campbell. The coordinator enquired if there were any further nominations. As no further nominations were received Mr Flynn declared Cllr Crowe duly elected as Cathaoirleach. Cllr Crowe then took the chair for the remainder of the meeting. Cllr Crowe thanked his proposer and seconder stating that he was deeply honoured and humbled to become the first chair of the new Municipal District of Carrickmacross - Castleblayney. Cllr Crowe gave his commitment to work along with coordinator, staff and elected members to ensure the Municipal District can work for the benefit of the people. -

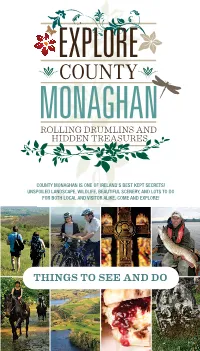

Things to See and Do Our Monaghan Story

COUNTY MONAGHAN IS ONE OF IRELAND'S BEST KEPT SECRETS! UNSPOILED LANDSCAPE, WILDLIFE, BEAUTIFUL SCENERY, AND LOTS TO DO FOR BOTH LOCAL AND VISITOR ALIKE. COME AND EXPLORE! THINGS TO SEE AND DO OUR MONAGHAN STORY OFTEN OVERLOOKED, COUNTY MONAGHAN’S VIBRANT LANDSCAPE - FULL OF GENTLE HILLS, GLISTENING LAKES AND SMALL IDYLLIC MARKET TOWNS - PROVIDES A TRUE GLIMPSE INTO IRISH RURAL LIFE. THE COUNTY IS WELL-KNOWN AS THE BIRTHPLACE OF THE POET PATRICK KAVANAGH AND THE IMAGES EVOKED BY HIS POEMS AND PROSE RELATE TO RURAL LIFE, RUN AT A SLOW PACE. THROUGHOUT MONAGHAN THERE ARE NO DRAMATIC VISUAL SHIFTS. NO TOWERING PEAKS, RAGGED CLIFFS OR EXPANSIVE LAKES. THIS IS AN AREA OFF THE WELL-BEATEN TOURIST TRAIL. A QUIET COUNTY WITH A SENSE OF AWAITING DISCOVERY… A PALPABLE FEELING OF GENUINE SURPRISE . HOWEVER, THERE’S A SIDE TO MONAGHAN THAT PACKS A LITTLE MORE PUNCH THAN THAT. HERE YOU WILL FIND A FRIENDLY ATMOSPHERE AND ACTIVITIES TO SUIT MOST INTERESTS WITH GLORIOUS GREENS FOR GOLFING , A HOST OF WATERSPORTS AND OUTDOOR PURSUITS AND A WEALTH OF HERITAGE SITES TO WHET YOUR APPETITE FOR ADVENTURE AND DISCOVERY. START BY TAKING A LOOK AT THIS BOOKLET AND GET EXPLORING! EXPLORE COUNTY MONAGHAN TO NORTH DONEGAL/DERRY AWOL Derrygorry / PAINTBALL Favour Royal BUSY BEE Forest Park CERAMICS STUDIO N2 MULLAN CARRICKROE CASTLE LESLIE ESTATE EMY LOUGH CASTLE LESLIE EQUESTRIAN CENTRE EMY LOUGH EMYVALE LOOPED WALK CLONCAW EQUESTRIAN CENTRE Bragan Scenic Area MULLAGHMORE EQUESTRIAN CENTRE GLASLOUGH TO ARMAGH KNOCKATALLON TYDAVNET CASTLE LESLIE TO BELFAST SLIABH BEAGH TOURISM CENTRE Hollywood Park R185 SCOTSTOWN COUNTY MUSEUM TYHOLLAND GARAGE THEATRE LEISURE CENTRE N12 RALLY SCHOOL MARKET HOUSE BALLINODE ARTS CENTRE R186 MONAGHAN VALLEY CLONES PEACE LINK MONAGHAN PITCH & PUTT SPORTS FACILITY MONAGHAN CLONES HERITAGE HERITAGE TRAIL TRAIL R187 5 N2 WILDLIFE ROSSMORE PARK & HERITAGE CLONES ULSTER ROSSMORE GOLF CLUB CANAL STORES AND SMITHBOROUGH CENTRE CARA ST. -

Roinn Cosanta. Bureau of Military

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21 STATEMENT BY WITNESS 576 DOCUMENT NO. W.S. Witness Eugene Sherry, Clontibret, Castleblayney, Co. Monaghan. Identity. Member Of Clontibret (Co. Monaghan) Company Irish Volunteers, 1916 ; Captain same Company, 1919 Subject. The (a) Irish Volunteers, Co. Monaghan, 1914 ; (b) Military activities, Co. Monaghan, 1920-1921. Conditions, If Any, Stipulated by Witness. S.1831. File No Form B.S.M.2 Statement by Eugene Sherry, Clontibret, Castleblaney, Co. Monaghan. I joined the Volunteers early probably before 1916. This organisation was of little value. We took part in drills and training. A man named Cusack came from Monaghan town and put us through training exercises. Easter Week 1916 passed without any local incident taking. place. The start of re-organising the Volunteers after 1916 took place in our area about 1919. I then joined the Clontibret Company. I was the first Company O/C and remained in charge of the Company until 1922. About thirty men joined at the start of the Company and the membership gradually increased up to the Truce when we had 63 or 64 on the rolls. Clontibret Company was part of the Monaghan town Battalion from 1919 onwards. In 1919 we had little arms some shotguns, a few pin fire revolvers-of antiquated make and some ammunition for the revolvers. We had to rely on what we had or on what we got by raiding forearms. I purchased a few revolvers myself. This was all the purchase of arms as far as I know in the Company area. In 1920 at the general raid for arms we made a canvass amongst all friendly houses within the Company area and we handed over a number of shotguns.