Full Text Thesis (937.3Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 ANNUAL MEETING from Imitation to Innovation

2018 ANNUAL MEETING From Imitation to Innovation NOVEMBER 10 – 12, 2018 DOHA, QATAR HOSTED BY INDEX WELCOME ………………………………………………………………………… 3 AGENDA …………………………………………………………………………... 4 GROUP BREAKOUTS …………………………………………………………… 10 GOVERNING BOARD …………………………………………………………… 13 DOCTRINAL STUDY GROUPS ………………………………………………… 14 UNIVERSITIES ATTENDING …………………………………………………… 15 BOARD OF GOVERNORS ATTENDEES ……………………………………... 17 QATAR UNIVERSITY, COLLEGE OF LAW ATTENDEES …………………. 21 JUDICIAL ATTENDEES …………………………………………………………. 25 ATTENDEES ……………………………………………………………………… 29 SECRETARIAT …………………………………………………………………… 58 SINGAPORE DECLARATION ………………………………………………….. 59 MADRID PROTOCOL ……………………………………………………………. 61 JUDICIAL STANDARDS OF A LEGAL EDUCATION ……………………….. 62 SELF-ASSESSMENT REPORT ………………………………………………… 63 EVALUATION, ASSISTANCE, AND CERTIFICATION PROGRAM ……….. 66 2 WELCOME On behalf of all the members of the International Association of Law Schools Board of Governors, we want to welcome each and every one of you to our 2018 Annual Meeting. This is our eleventh annual meeting where over 115 law teachers from more than 30 countries have gathered together to discuss and formulate new strategies to improve legal education globally. Almost half of our participants are senior law school leaders (deans, vice deans and associate deans). We warmly welcome all the familiar faces from these many years – welcome and thank you for your continued engagement in advancing the cause of improving legal education globally. For those who are new, a special warm welcome from our community. Please meet your colleagues from around the world. We look forward to working with you in this challenging and engaging effort. The IALS is a non-political, non-profit learned society of more than 160 law schools and departments from over 55 countries representing more than 7,500 law faculty members. One of our primary missions is the improvement of law schools and conditions of legal education throughout the world by learning from each other. -

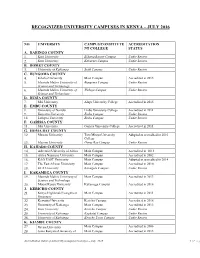

Recognized University Campuses in Kenya – July 2016

RECOGNIZED UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES IN KENYA – JULY 2016 NO. UNIVERSITY CAMPUS/CONSTITUTE ACCREDITATION NT COLLEGE STATUS A. BARINGO COUNTY 1. Kisii University Eldama Ravine Campus Under Review 2. Kisii University Kabarnet Campus Under Review B. BOMET COUNTY 3. University of Kabianga Sotik Campus Under Review C. BUNGOMA COUNTY 4. Kibabii University Main Campus Accredited in 2015 5. Masinde Muliro University of Bungoma Campus Under Review Science and Technology 6. Masinde Muliro University of Webuye Campus Under Review Science and Technology D. BUSIA COUNTY 7. Moi University Alupe University College Accredited in 2015 E. EMBU COUNTY 8. University of Nairobi Embu University College Accredited in 2011 9. Kenyatta University Embu Campus Under Review 10. Laikipia University Embu Campus Under Review F. GARISSA COUNTY 11. Moi University Garissa University College Accredited in 2011 G. HOMA BAY COUNTY 12. Maseno University Tom Mboya University Adopted as accredited in 2016 College 13. Maseno University Homa Bay Campus Under Review H. KAJIADO COUNTY 14. Adventist University of Africa Main Campus Accredited in 2013 15. Africa Nazarene University Main Campus Accredited in 2002 16. KAG EAST University Main Campus Adopted as accredited in 2014 17. The East African University Main Campus Accredited in 2010 18. KCA University Kitengela Campus Under Review I. KAKAMEGA COUNTY 19. Masinde Muliro University of Main Campus Accredited in 2013 Science and Technology 20. Mount Kenya University Kakamega Campus Accredited in 2016 J. KERICHO COUNTY 21. Kenya Highlands Evangelical Main Campus Accredited in 2011 University 22. Kenyatta University Kericho Campus Accredited in 2016 23. University of Kabianga Main Campus Accredited in 2013 24. -

Funded Degree Programmes and Partners Involved in Sub-Sahara Africa (2020/21)

Funded degree programmes and partners involved in Sub-Sahara Africa (2020/21) Regional universities/networks are participating in the scholarship programme as partner institutions Call for application West and Central Africa: Deadline: February, 10th 2021 West and Central Africa Benin • University of Abomey – Calavi (UAC) Faculty of Agronomic Sciences, Mathematics (Master, PhD) International Chair in Mathematical Physics and Applications (CIPMA), Natural Sciences (Master, PhD) Burkina Faso • International Institute for Water and Environmental Engineering (2iE), Engineering (Master, PhD) Ghana • University for Development Studies (UDS), Department of Public Health, Medicine - Public Health (Master Phil, Master Sc) • University of Ghana, Regional Institute for Population Studies (RIPS), Humanities / Political Science (Master, PhD) West African Center for Crop Improvement (WACCI), University of Ghana, Agricultural Sciences (Master, PhD) Nigeria • University of Ibadan, Subject fields: Fisheries Management and Energy Studies (Master) Network • Centre d 'Etudes Régional pour l'Amélioration de l'Adaptation à la Sécheresse (CERAAS), Agricultural Sciences (Master, PhD) Eastern Africa Call for application Eastern Africa: Deadline: December, 15th 2020 Ethiopia Addis Ababa University - IPSS, Subject field: Global & Area Studies (PhD) • Hawassa University - Wondo Genet College of Forestry and Natural Resources (WGCF), Agro-Forestry (Master) Kenya • Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (JKUAT), Information Technology (PhD), Mechanical -

Report on the 1St ACM SIGIR/SIGKDD Africa School on Machine Learning for Data Mining and Search

SCHOOL REPORT Report on the 1st ACM SIGIR/SIGKDD Africa School on Machine Learning for Data Mining and Search Ben Carterette Hussein Suleman Douglas W. Oard Spotify / University of Delaware University of Cape Town University of Maryland [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract We report on the inception, organization, and activities of the 1st ACM SIGIR/SIGKDD Africa School on Machine Learning for Data Mining and Search, which took place at the University of Cape Town in South Africa January 14{18, 2019. 1 Introduction In January of 2019, ACM SIGIR and ACM SIGKDD co-sponsored the 1st SIGIR/SIGKDD Africa School on Machine Learning for Data Mining and Search,1 which took place at the University of Cape Town in South Africa. The event was conceived by SIGIR members with the aims of increasing opportunities in research from traditionally underserved communities, growing the IR and data mining communities in sub-Saharan Africa, and expanding the horizons of IR and data mining research. This is a report on the inception, organization, and activities of the event. Section 2 gives context on how the event came to be. In Section 3 we describe the organizational decisions and activities including committees, funding, calls for participation, and scientific program. Section 4 details the five days of the event, including lectures, labs, and other sessions. In Section 5 we detail the next steps for the initiative. 2 From inception to inauguration The inception of the event dates to the SIGIR conference in Tokyo in 2017. That year, the SIGIR Executive Committee organized the first SIGIR Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) lunch for con- ference attendees. -

Annual Report 2016 Innovation Research

Strathmore University Annual Report 2016 Innovation Research Annual Report and Financial Statements 2016 Strathmore University Annual Report 2016 1 A T HMO R E Strathmore University Annual Report 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Strathmore at a glance 3 1 Our Coat of Arms 4 History of Strathmore 5 Our Strategic pillars 9 Our Diversity 10 Year in Review – 2016 11 Strategic Review 13 2 Capitals 14 Business Model 15 Our Strategic priorities 16 Key Performance Indicators 19 3 2016 Highlights 20 a. Financial KPIs 20 b. Non- Financial KPIs 25 4 Stakeholder Analysis & Engagement 27 5 Governance & Management Report 36 a. Profile of University Council members 37 b. Statement from Chair of University Council 45 c. Vice Chancellor’s Report 47 d. Corporate Governance Report 49 6 Risk Management Report 57 7 Sustainability Report 60 a. Our People – Human & Intellectual capital 61 b. Environmental Initiatives 64 c. Community Engagement initiatives 66 Financial Aid 71 8 Research Report 73 9 Student Affairs Report 77 10 Schools Reports 83 11 Financial Statements for the year ended Dec 2016 114 2 Strathmore University Annual Report 2016 Strathmore at a glance 3 Strathmore University Annual Report 2016 Who we are Our Coat of Arms The Three Hearts represent the three races which, in 1961 when the University started, were segregated (Gold) Gold means Yellow: in the colonial system of education. eternity, perfection. The heart represents the person, (Azure) Sky blue means Blue: since it is taken as the source of all high ideals, high aims. our actions, and the source of love. (Gules) Blood red means Red: The fact that the three hearts all sacrifice, love, fortitude. -

Statistics Education in Kenya: Developments and Challenges

Statistics Education in Kenya: Developments and Challenges John W. Odhiambo; Silas Onyango Strathmore University, Ole Sangale Road, Madaraka Estate, PO Box 59857, 00200, Nairobi, Kenya. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 1. Introduction Sessions In the twenty- first century countries of the world, whether developed or developing are all aiming to become IPMs knowledge based economies (World Bank, 2002; Abbas Bazargan, 2005). Kenya is not an exception. In Kenya today greater value is placed on statistical information, statistical skills and statistical knowledge. Student enrollment in statistics education programmes in universities in Kenya has increased rapidly in the past two decades. This expansion has brought with it attendant challenges shared by both developed and developing countries (Godwin Ogum, 1998; Abbas Bazargan, 2005). Odhiambo (2002) reviewed the teaching of statistics at university level in Kenya. In this paper the aim is to examine the developments which have taken place in statistics education and how the rapid increase in student numbers and technological advancement has impacted on the teaching of statistics in the country. The paper is arranged as follows: In section two we review the development of statistics education in Kenya. In section three we present the teaching of statistics in Universities in Kenya. Here organizational setting, student enrolment, curriculum design, the statistics teaching staff and assessment and quality assurance are presented. In section four we indicate some of the common challenges facing statistics education in Kenya and in section five we present some suggestions for future development of teaching and learning of statistics in universities in Kenya. 2. Statistics Education in Kenya Kenya runs an 8-4-4 system of education; that is eight years of primary education which most pupils enter at the age of 6 years; four year of secondary education; and four years of university education which leads to Sessions IPMs the award of a bachelor’s degree. -

Download Revised Book of Abstracts for 2016 Conference

6th Annual conference African Accounting and Finance Conference BOOK OF ABSTRACTS 30th August - 2nd September, 2016; Weston Hotel, Nairobi- Kenya 1 Our Sponsors The Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA) supports the AAFA Conferences We gratefully acknowledge the support of CIMA’s General Charitable Trust Welcome Note Dear Delegates It gives us a great pleasure to welcome you to the 6th African Accounting and Finance Association (AAFA) Conference organized by Strathmore University and AAFA at Weston hotel. It is our privilege to host delegates from a variety of countries from within, and beyond, Africa. The papers and presentations cover topics ranging from accounting, governance, financial markets, and corporate social responsibility. Such a diversity of individuals and topics should guarantee an interesting and stimulating few days. We wish to express our gratitude to Professor Teerooven Soobaroyen, and Dr. Ibrahim Bedi for their great support in organizing the AAFA 2016 conference. We are also pleased to welcome you to the AAFA 2016 Annual Emerging Scholars Colloquium which will take place on Tuesday 30th August in Strathmore University. The colloquium will bring young researchers (Doctoral Students) together to present their work-in-progress and receive feedback from leading researchers in the field. We would also want to express our sincere gratitude to the international scientific committee members for their reviews and comments, and for enabling the preparation of an excellent programme. The keynote speech will be delivered by esteemed scholar Professor Dr. Holger Daske, University of Mannheim (Germany) on: “Reflections on the IFRS experiment and unchartered territories of accounting harmonization: Lessons learned and future research opportunities”. -

STRENGTHENING UNIVERSITY-INDUSTRY LINKAGES in AFRICA a Study on Institutional Capacities and Gaps

STRENGTHENING UNIVERSITY-INDUSTRY LINKAGES IN AFRICA A Study on Institutional Capacities and Gaps JOHN SSEBUWUFU, TERALYNN LUDWICK AND MARGAUX BÉLAND Funded by the Canadian Government through CIDA Canadian International Agence canadienne de Development Agency développement international STRENGTHENING UNIVERSITY-INDUSTRY LINKAGES IN AFRICA: A Study on Institutional Capacities and Gaps Prof. John Ssebuwufu Director, Research & Programmes Association of African Universities (AAU) Teralynn Ludwick Research Officer AAU Research and Programmes Department / AUCC Partnership Programmes Margaux Béland Director, Partnership Programmes Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada (AUCC) Currently on secondment to the Canadian Bureau for International Education (CBIE) Strengthening University-Industry Linkages in Africa: A Study of Institutional Capacities and Gaps @ 2012 Association of African Universities (AAU) All rights reserved Printed in Ghana Association of African Universities (AAU) 11 Aviation Road Extension P.O. Box 5744 Accra-North Ghana Tel: +233 (0) 302 774495/761588 Fax: +233 (0) 302 774821 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Web site: http://www.aau.org This study was undertaken by the Association of African Universities (AAU) and the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada (AUCC) as part of the project, Strengthening Higher Education Stakeholder Relations in Africa (SHESRA). The project is generously funded by Government of Canada through the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). The views and opinions -

Annual Report (2018)

ACRONYMS Association of Chartered Certified KPI Key Performance Indicators ACCA Accountants KRA Kenya Revenue Authority Association of Commonwealth ACU Kshs Kenya Shillings Universities MBA Master of Business Administration BAC Bachelor of Arts in Communication MC Management Committee Bachelor of Arts in International BIS MOU Memorandum of Understanding Studies MW Megawatts Bachelor of Arts in Development BDP Association of Schools of Public Studies and Philosophy NASPAA Affairs and Administration BPO Business Process Outsourcing National Environmental Management CAF Confederation of African Football NEMA and Authority CDE Challenge Driven Education NITA National Industrial Training Authority CEO Chief Executive Officer NPS National Police Service Centre for Intellectual Property and CIPIT Partnership for Enhanced Blended Information Technology PEBL Learning Centre for IT Security Privacy and CISPA PIC Policy Innovation Centre Accountability PhD Doctor of Philosophy Committee of Sponsoring COSO Organisational Framework PPA Power Purchase Agreement CPA Certified Public Accountant Prof. Professor CUE Commission of University Education PV Photovoltaic UK Department for International Sub Saharan Africa International DFID SAIMUN Development Model United Nation Conference Strathmore University Business DRAMASOC Drama Society Club SBS School DVC Deputy Vice Chancellor SDGs Sustainable Development Goals Emirates Academy of Hospitality EAHM Management SEDC Enterprise Development Centre East and Central Africa Social Strathmore Extractives Industries -

March 2008 Strathmore University 2 SU the University with Highest Web Presence in East Africa

ALUMNI S NEWSLETTERU CONTENTS.................... 2 :: SU the university with highest web presence in East Africa :: Proclaiming peace atop Mt. Kilimanjaro 3 :: The Overlooked Factor 4 :: Students documentary launched as best of 2007 are awarded 5 :: Sperling and McFie decorated by state :: Model UN debate held in SU 6 :: SBS hosts lecture on patient safety management :: 4th Annual Careers Fair a success 7 :: Keri Residence at three 8 :: SU to launch two new degree programs March 2008 Strathmore University 2 SU the university with highest web presence in East Africa A computer lab at Strathmore University. The University has over 400 computers with email and internet at the disposal of its students Strathmore University is the Universities” is an initiative of the and scholarly communication of highest ranked university in East Cybermetrics Lab, a research group scientific knowledge. This is a Africa in the latest webometrics belonging to the Centro Superior de new emerging discipline called ranking of universities worldwide Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC) Cybermetrics. dated January 2008. the largest public research body in The Cybermetrics Lab has designed SU is ranked position 21 in Africa Spain. and applied quantitative indicators up from position 50 in April 2007. Cybermetrics Lab is devoted to the that measure the research and The University of Dar es Salaam is quantitative analysis of the Internet scientific activity on the web. ranked position 22. and Web contents especially those For more details please see: http:// The “Webometrics Ranking of World related to the processes of generation www.webometrics.info/about.html Proclaiming peace atop Mt Kilimanjaro From Left Luis Franceschi, Damian Maingi, George Thinwa, Austin Omeno, Odilon Dizon, James Muriuki and John Matogo. -

Annual Report (2010)

STRATHMORE UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2010 STRATHMORE UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Strathmore UNIVERSITY FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2010 ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR 1 ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2010 STRATHMORE UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2010 ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL 2 STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2010 STRATHMORE UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2010 CONTENTS NO MANAGEMENT BOARD 4 UNIVERSITY COUNCIL 5 STATEMENT FROM THE CHAIRMAN 6 VICE CHANCELLOR’S MESSAGE 7 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 8 MANAGEMENT REPORT 9 FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE 11 COMMUNITY OUTREACH 16 NEW SCHOOL AND PROGRAMMES 17 SPORTS 17 GENERAL INFORMATION 19 UNIVERSITY COUNCIL’S REPORT 20 STATEMENT OF UNIVERSITY COUNCIL’S RESPONSIBILITIES 21 REPORT OF THE INDEPENDENT AUDITOR TO THE MEMBERS OF THE STRATHMORE UNIVERSITY 22 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS: 23 STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION 23 STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN ACCUMULATED CAPITAL FUND 25 STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS 26 NOTES 27-58 Strathmore UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR 3 ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2010 STRATHMORE UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2010 MANAGEMENT BOARD Prof John Odhiambo, Vice Chancellor Dr Charles Sotz, University Secretary Ms Stella Mwangi, Administration Services Manager Prof Izael Pereira Da Silva, Deputy Mr Daniel Kiilur, Head of Support Vice Chacellor, -

Influence of Marketing Strategies on Performance of Strathmore University

INFLUENCE OF MARKETING STRATEGIES ON PERFORMANCE OF STRATHMORE UNIVERSITY, KENYA BY JACQUELINE NGURE A RESEARCH PROJECT PRESENTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION DEGREE, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI NOVEMBER 2018 DECLARATION I, the undersigned, declare that this is my original work and has not been presented to any institution or university other than the University of Nairobi for examination. Signed: _____________________Date: __________________________ JACQUELINE NGURE D61/79038/2015 This research project has been submitted for examination with my approval as the University Supervisor. Signed: _____________________Date: __________________________ PROF. JUSTUS MUNYOKI Associate Professor, Department of Business Administration Business School, University of Nairobi ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my entire family who gave me invaluable moral support throughout the period. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to sincerely acknowledge my supervisor Prof Justus Munyoki , who has guided me enthusiastically through the research project. His support is invaluable. I would also like to acknowledge my family members, friends and colleagues whose support has made it possible for me to come this far in my academics. I also acknowledge my course mates and lecturers at the University of Nairobi for sharing their knowledge and supporting me through the academic period. iv ABSTRACT The general objective of the study was to determine the effect of marketing strategies on performance of Strathmore University. Specifically, the study sought to determine the marketing strategies adopted by Strathmore University and establish the effect of marketing strategies on performance of Strathmore University. This study was based on three theories namely Ansoff growth strategy theory, the resource-based view theory of the firm and the competence-based strategy theory.